Delegation of Quantum Computations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity Theory Lecture 9 Co-NP Co-NP-Complete

Complexity Theory 1 Complexity Theory 2 co-NP Complexity Theory Lecture 9 As co-NP is the collection of complements of languages in NP, and P is closed under complementation, co-NP can also be characterised as the collection of languages of the form: ′ L = x y y <p( x ) R (x, y) { |∀ | | | | → } Anuj Dawar University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory NP – the collection of languages with succinct certificates of Easter Term 2010 membership. co-NP – the collection of languages with succinct certificates of http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/0910/Complexity/ disqualification. Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Complexity Theory 3 Complexity Theory 4 NP co-NP co-NP-complete P VAL – the collection of Boolean expressions that are valid is co-NP-complete. Any language L that is the complement of an NP-complete language is co-NP-complete. Any of the situations is consistent with our present state of ¯ knowledge: Any reduction of a language L1 to L2 is also a reduction of L1–the complement of L1–to L¯2–the complement of L2. P = NP = co-NP • There is an easy reduction from the complement of SAT to VAL, P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ namely the map that takes an expression to its negation. P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ VAL P P = NP = co-NP ∈ ⇒ P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ VAL NP NP = co-NP ∈ ⇒ Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Complexity Theory 5 Complexity Theory 6 Prime Numbers Primality Consider the decision problem PRIME: Another way of putting this is that Composite is in NP. -

EXPSPACE-Hardness of Behavioural Equivalences of Succinct One

EXPSPACE-hardness of behavioural equivalences of succinct one-counter nets Petr Janˇcar1 Petr Osiˇcka1 Zdenˇek Sawa2 1Dept of Comp. Sci., Faculty of Science, Palack´yUniv. Olomouc, Czech Rep. [email protected], [email protected] 2Dept of Comp. Sci., FEI, Techn. Univ. Ostrava, Czech Rep. [email protected] Abstract We note that the remarkable EXPSPACE-hardness result in [G¨oller, Haase, Ouaknine, Worrell, ICALP 2010] ([GHOW10] for short) allows us to answer an open complexity ques- tion for simulation preorder of succinct one counter nets (i.e., one counter automata with no zero tests where counter increments and decrements are integers written in binary). This problem, as well as bisimulation equivalence, turn out to be EXPSPACE-complete. The technique of [GHOW10] was referred to by Hunter [RP 2015] for deriving EXPSPACE-hardness of reachability games on succinct one-counter nets. We first give a direct self-contained EXPSPACE-hardness proof for such reachability games (by adjust- ing a known PSPACE-hardness proof for emptiness of alternating finite automata with one-letter alphabet); then we reduce reachability games to (bi)simulation games by using a standard “defender-choice” technique. 1 Introduction arXiv:1801.01073v1 [cs.LO] 3 Jan 2018 We concentrate on our contribution, without giving a broader overview of the area here. A remarkable result by G¨oller, Haase, Ouaknine, Worrell [2] shows that model checking a fixed CTL formula on succinct one-counter automata (where counter increments and decre- ments are integers written in binary) is EXPSPACE-hard. Their proof is interesting and nontrivial, and uses two involved results from complexity theory. -

Dspace 6.X Documentation

DSpace 6.x Documentation DSpace 6.x Documentation Author: The DSpace Developer Team Date: 27 June 2018 URL: https://wiki.duraspace.org/display/DSDOC6x Page 1 of 924 DSpace 6.x Documentation Table of Contents 1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________ 7 1.1 Release Notes ____________________________________________________________________ 8 1.1.1 6.3 Release Notes ___________________________________________________________ 8 1.1.2 6.2 Release Notes __________________________________________________________ 11 1.1.3 6.1 Release Notes _________________________________________________________ 12 1.1.4 6.0 Release Notes __________________________________________________________ 14 1.2 Functional Overview _______________________________________________________________ 22 1.2.1 Online access to your digital assets ____________________________________________ 23 1.2.2 Metadata Management ______________________________________________________ 25 1.2.3 Licensing _________________________________________________________________ 27 1.2.4 Persistent URLs and Identifiers _______________________________________________ 28 1.2.5 Getting content into DSpace __________________________________________________ 30 1.2.6 Getting content out of DSpace ________________________________________________ 33 1.2.7 User Management __________________________________________________________ 35 1.2.8 Access Control ____________________________________________________________ 36 1.2.9 Usage Metrics _____________________________________________________________ -

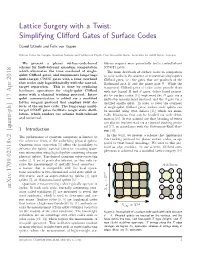

Lattice Surgery with a Twist: Simplifying Clifford Gates of Surface Codes

Lattice Surgery with a Twist: Simplifying Clifford Gates of Surface Codes Daniel Litinski and Felix von Oppen Dahlem Center for Complex Quantum Systems and Fachbereich Physik, Freie Universit¨at Berlin, Arnimallee 14, 14195 Berlin, Germany We present a planar surface-code-based bilizers requires more potentially faulty controlled-not scheme for fault-tolerant quantum computation (CNOT) gates. which eliminates the time overhead of single- The main drawback of surface codes in comparison qubit Clifford gates, and implements long-range to color codes is the absence of transversal single-qubit multi-target CNOT gates with a time overhead Clifford gates, i.e., the gates that are products of the that scales only logarithmically with the control- Hadamard gate H and the phase gate S. While the target separation. This is done by replacing transversal Clifford gates of color codes provide them hardware operations for single-qubit Clifford with fast logical H and S gates, defect-based propos- gates with a classical tracking protocol. Inter- als for surface codes [14] implement the H gate via a qubit communication is added via a modified multi-step measurement protocol, and the S gate via a lattice surgery protocol that employs twist de- distilled ancilla qubit. In order to lower the overhead fects of the surface code. The long-range multi- of single-qubit Clifford gates, surface code qubits can target CNOT gates facilitate magic state distil- be encoded using twist defects [15], which are essen- lation, which renders our scheme fault-tolerant tially Majoranas that can be braided via code defor- and universal. mation [16]. -

Interactive Proofs 1 1 Pspace ⊆ IP

CS294: Probabilistically Checkable and Interactive Proofs January 24, 2017 Interactive Proofs 1 Instructor: Alessandro Chiesa & Igor Shinkar Scribe: Mariel Supina 1 Pspace ⊆ IP The first proof that Pspace ⊆ IP is due to Shamir, and a simplified proof was given by Shen. These notes discuss the simplified version in [She92], though most of the ideas are the same as those in [Sha92]. Notes by Katz also served as a reference [Kat11]. Theorem 1 ([Sha92]) Pspace ⊆ IP. To show the inclusion of Pspace in IP, we need to begin with a Pspace-complete language. 1.1 True Quantified Boolean Formulas (tqbf) Definition 2 A quantified boolean formula (QBF) is an expression of the form 8x19x28x3 ::: 9xnφ(x1; : : : ; xn); (1) where φ is a boolean formula on n variables. Note that since each variable in a QBF is quantified, a QBF is either true or false. Definition 3 tqbf is the language of all boolean formulas φ such that if φ is a formula on n variables, then the corresponding QBF (1) is true. Fact 4 tqbf is Pspace-complete (see section 2 for a proof). Hence to show that Pspace ⊆ IP, it suffices to show that tqbf 2 IP. Claim 5 tqbf 2 IP. In order prove claim 5, we will need to present a complete and sound interactive protocol that decides whether a given QBF is true. In the sum-check protocol we used an arithmetization of a 3-CNF boolean formula. Likewise, here we will need a way to arithmetize a QBF. 1.2 Arithmetization of a QBF We begin with a boolean formula φ, and we let n be the number of variables and m the number of clauses of φ. -

Interactive Proofs for Quantum Computations

Innovations in Computer Science 2010 Interactive Proofs For Quantum Computations Dorit Aharonov Michael Ben-Or Elad Eban School of Computer Science, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: The widely held belief that BQP strictly contains BPP raises fundamental questions: Upcoming generations of quantum computers might already be too large to be simulated classically. Is it possible to experimentally test that these systems perform as they should, if we cannot efficiently compute predictions for their behavior? Vazirani has asked [21]: If computing predictions for Quantum Mechanics requires exponential resources, is Quantum Mechanics a falsifiable theory? In cryptographic settings, an untrusted future company wants to sell a quantum computer or perform a delegated quantum computation. Can the customer be convinced of correctness without the ability to compare results to predictions? To provide answers to these questions, we define Quantum Prover Interactive Proofs (QPIP). Whereas in standard Interactive Proofs [13] the prover is computationally unbounded, here our prover is in BQP, representing a quantum computer. The verifier models our current computational capabilities: it is a BPP machine, with access to few qubits. Our main theorem can be roughly stated as: ”Any language in BQP has a QPIP, and moreover, a fault tolerant one” (providing a partial answer to a challenge posted in [1]). We provide two proofs. The simpler one uses a new (possibly of independent interest) quantum authentication scheme (QAS) based on random Clifford elements. This QPIP however, is not fault tolerant. Our second protocol uses polynomial codes QAS due to Ben-Or, Cr´epeau, Gottesman, Hassidim, and Smith [8], combined with quantum fault tolerance and secure multiparty quantum computation techniques. -

Distribution of Units of Real Quadratic Number Fields

Y.-M. J. Chen, Y. Kitaoka and J. Yu Nagoya Math. J. Vol. 158 (2000), 167{184 DISTRIBUTION OF UNITS OF REAL QUADRATIC NUMBER FIELDS YEN-MEI J. CHEN, YOSHIYUKI KITAOKA and JING YU1 Dedicated to the seventieth birthday of Professor Tomio Kubota Abstract. Let k be a real quadratic field and k, E the ring of integers and the group of units in k. Denoting by E( ¡ ) the subgroup represented by E of × ¡ ¡ ( k= ¡ ) for a prime ideal , we show that prime ideals for which the order of E( ¡ ) is theoretically maximal have a positive density under the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis. 1. Statement of the result x Let k be a real quadratic number field with discriminant D0 and fun- damental unit (> 1), and let ok and E be the ring of integers in k and the set of units in k, respectively. For a prime ideal p of k we denote by E(p) the subgroup of the unit group (ok=p)× of the residue class group modulo p con- sisting of classes represented by elements of E and set Ip := [(ok=p)× : E(p)], where p is the rational prime lying below p. It is obvious that Ip is inde- pendent of the choice of prime ideals lying above p. Set 1; if p is decomposable or ramified in k, ` := 8p 1; if p remains prime in k and N () = 1, p − k=Q <(p 1)=2; if p remains prime in k and N () = 1, − k=Q − : where Nk=Q stands for the norm from k to the rational number field Q. -

Glossary of Complexity Classes

App endix A Glossary of Complexity Classes Summary This glossary includes selfcontained denitions of most complexity classes mentioned in the b o ok Needless to say the glossary oers a very minimal discussion of these classes and the reader is re ferred to the main text for further discussion The items are organized by topics rather than by alphab etic order Sp ecically the glossary is partitioned into two parts dealing separately with complexity classes that are dened in terms of algorithms and their resources ie time and space complexity of Turing machines and complexity classes de ned in terms of nonuniform circuits and referring to their size and depth The algorithmic classes include timecomplexity based classes such as P NP coNP BPP RP coRP PH E EXP and NEXP and the space complexity classes L NL RL and P S P AC E The non k uniform classes include the circuit classes P p oly as well as NC and k AC Denitions and basic results regarding many other complexity classes are available at the constantly evolving Complexity Zoo A Preliminaries Complexity classes are sets of computational problems where each class contains problems that can b e solved with sp ecic computational resources To dene a complexity class one sp ecies a mo del of computation a complexity measure like time or space which is always measured as a function of the input length and a b ound on the complexity of problems in the class We follow the tradition of fo cusing on decision problems but refer to these problems using the terminology of promise problems -

The Weakness of CTC Qubits and the Power of Approximate Counting

The weakness of CTC qubits and the power of approximate counting Ryan O'Donnell∗ A. C. Cem Sayy April 7, 2015 Abstract We present results in structural complexity theory concerned with the following interre- lated topics: computation with postselection/restarting, closed timelike curves (CTCs), and approximate counting. The first result is a new characterization of the lesser known complexity class BPPpath in terms of more familiar concepts. Precisely, BPPpath is the class of problems that can be efficiently solved with a nonadaptive oracle for the Approximate Counting problem. Similarly, PP equals the class of problems that can be solved efficiently with nonadaptive queries for the related Approximate Difference problem. Another result is concerned with the compu- tational power conferred by CTCs; or equivalently, the computational complexity of finding stationary distributions for quantum channels. Using the above-mentioned characterization of PP, we show that any poly(n)-time quantum computation using a CTC of O(log n) qubits may as well just use a CTC of 1 classical bit. This result essentially amounts to showing that one can find a stationary distribution for a poly(n)-dimensional quantum channel in PP. ∗Department of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University. Work performed while the author was at the Bo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department, supported by Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship project number 626373. yBo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department. 1 Introduction It is well known that studying \non-realistic" augmentations of computational models can shed a great deal of light on the power of more standard models. The study of nondeterminism and the study of relativization (i.e., oracle computation) are famous examples of this phenomenon. -

![Arxiv:2003.09412V2 [Quant-Ph] 7 Jul 2021 Hadamard-Free Circuits Expose the Structure of the Clifford Group](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5281/arxiv-2003-09412v2-quant-ph-7-jul-2021-hadamard-free-circuits-expose-the-structure-of-the-clifford-group-935281.webp)

Arxiv:2003.09412V2 [Quant-Ph] 7 Jul 2021 Hadamard-Free Circuits Expose the Structure of the Clifford Group

Hadamard-free circuits expose the structure of the Clifford group Sergey Bravyi and Dmitri Maslov IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598, USA July 8, 2021 Abstract The Clifford group plays a central role in quantum randomized benchmarking, quantum tomography, and error correction protocols. Here we study the structural properties of this group. We show that any Clifford operator can be uniquely written in the canonical form F1HSF2, where H is a layer of Hadamard gates, S is a permutation of qubits, and Fi are parameterized Hadamard-free circuits chosen from suitable subgroups of the Clifford group. Our canonical form provides a one-to-one correspondence between Clifford operators and layered quantum circuits. We report a polynomial-time algorithm for computing the canonical form. We employ this canonical form to generate a random uniformly distributed n-qubit Clifford operator in runtime O(n2). The number of random bits consumed by the algorithm matches the information-theoretic lower bound. A surprising connection is highlighted between random uniform Clifford operators and the Mallows distribution on the symmetric group. The variants of the canonical form, one with a short Hadamard- free part and one allowing a circuit depth 9n implementation of arbitrary Clifford unitaries in the Linear Nearest Neighbor architecture are also discussed. Finally, we study computational quantum advantage where a classical reversible linear circuit can be implemented more efficiently using Clifford gates, and show an explicit example where such an advantage takes place. 1 Introduction Clifford circuits can be defined as quantum computations by the circuits with Phase (p), Hadamard (h), and cnot gates, applied to a computational basis state, such as |00...0i. -

Quantum Topological Error Correction Codes Are Capable of Improving the Performance of Clifford Gates

1 Quantum Topological Error Correction Codes Are Capable of Improving the Performance of Clifford Gates Daryus Chandra, Zunaira Babar, Hung Viet Nguyen, Dimitrios Alanis, Panagiotis Botsinis, Soon Xin Ng, and Lajos Hanzo Abstract—The employment of quantum error correction codes under certain conditions we can transform various classes of (QECCs) within quantum computers potentially offers a reli- powerful classical error correction codes into their quantum ability improvement for both quantum computation and com- counterparts, such as Quantum Turbo Codes (QTCs) [8], [9], munications tasks. However, incorporating quantum gates for performing error correction potentially introduces more sources Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (QLDPC) codes [10], of quantum decoherence into the quantum computers. In this [11], and Quantum Polar Codes (QPCs) [12], [13]. However, scenario, the primary challenge is to find the sufficient condition several challenges remain, hindering the immediate employ- required by each of the quantum gates for beneficially employing ment of these powerful QSCs in quantum computers. Firstly, QECCs in order to yield reliability improvements given that the the reliability of the state-of-the-art quantum gates is still quantum gates utilized by the QECCs also introduce quantum decoherence. In this treatise, we approach this problem by significantly lower compared to classical gates. For exam- firstly presenting the general framework of protecting quantum ple, the reliability of a two-qubit quantum gate is between gates by the amalgamation of the transversal configuration of 90:00% 99:90% across various technology platforms, such quantum gates and quantum stabilizer codes (QSCs), which can as spin− electronics, photonics, superconducting, trapped-ion, be viewed as syndrome-based QECCs. -

Lecture 16 1 Interactive Proofs

Notes on Complexity Theory Last updated: October, 2011 Lecture 16 Jonathan Katz 1 Interactive Proofs Let us begin by re-examining our intuitive notion of what it means to \prove" a statement. Tra- ditional mathematical proofs are static and are veri¯ed deterministically: the veri¯er checks the claimed proof of a given statement and is either convinced that the statement is true (if the proof is correct) or remains unconvinced (if the proof is flawed | note that the statement may possibly still be true in this case, it just means there was something wrong with the proof). A statement is true (in this traditional setting) i® there exists a valid proof that convinces a legitimate veri¯er. Abstracting this process a bit, we may imagine a prover P and a veri¯er V such that the prover is trying to convince the veri¯er of the truth of some particular statement x; more concretely, let us say that P is trying to convince V that x 2 L for some ¯xed language L. We will require the veri¯er to run in polynomial time (in jxj), since we would like whatever proofs we come up with to be e±ciently veri¯able. A traditional mathematical proof can be cast in this framework by simply having P send a proof ¼ to V, who then deterministically checks whether ¼ is a valid proof of x and outputs V(x; ¼) (with 1 denoting acceptance and 0 rejection). (Note that since V runs in polynomial time, we may assume that the length of the proof ¼ is also polynomial.) The traditional mathematical notion of a proof is captured by requiring: ² If x 2 L, then there exists a proof ¼ such that V(x; ¼) = 1.