A Universal Multiphase Mission Execution Automaton (Mea) with Prolog Implementation for Unmanned Untethered Vehicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programming Languages Shouldn't and Needn't Be Turing Complete

Programming languages shouldn't and needn't be Turing complete GABRIEL PICKARD Any algorithmic problem faced by application programmers in the wild1 can in principle be solved using a Turing incomplete programming language. [Rice 1953] suggests that Turing completeness bears a heavy price, fundamentally limiting the ability of automatic assistants to help programmers be more productive, create less bugs and write safer software. Nevertheless, no mainstream general purpose programming language is Turing incomplete, with the arguable exception of SQL. We identify historical causes for this discrepancy and argue that the current moment offers better conditions for introducing Turing incompleteness. We present an approach to eliminating Turing completeness during the language design process, with several examples suitable languages targeting application development. Designers of modern practical programming languages should strongly consider evading Turing completeness and enabling better verification, security, automated testing and distributed computing. 1 CEDING POWER TO GAIN CONTROL 1.1 Turing completeness considered harmful The history of programming language design2 has been a history of removing powers which were considered harmful (cf. [Dijkstra 1966]) and replacing them with tamer, more manageable and automated constructs, including: (1) Direct access to CPU registers and instructions ! higher level compilers (2) GOTO ! structured programming (3) Manual memory management ! garbage collection (and borrow checkers) (4) Arbitrary access ! information hiding (5) Side-effects and mutability ! pure functions and persistent data structures While not all application domains benefit from all the replacement steps above3, it appears as if removing some expressive power can often enable a new kind of programming, even a new kind of application altogether. -

Turing Machines

Basics Computability Complexity Turing Machines Bruce Merry University of Cape Town 10 May 2012 Bruce Merry Turing Machines Basics Computability Complexity Outline 1 Basics Definition Building programs Turing Completeness 2 Computability Universal Machines Languages The Halting Problem 3 Complexity Non-determinism Complexity classes Satisfiability Bruce Merry Turing Machines Basics Definition Computability Building programs Complexity Turing Completeness Outline 1 Basics Definition Building programs Turing Completeness 2 Computability Universal Machines Languages The Halting Problem 3 Complexity Non-determinism Complexity classes Satisfiability Bruce Merry Turing Machines Basics Definition Computability Building programs Complexity Turing Completeness What Are Turing Machines? Invented by Alan Turing Hypothetical machines Formalise “computation” Alan Turing, 1912–1954 Bruce Merry Turing Machines If in state si and tape contains qj , write qk then move left/right and change to state sm A finite set of states, including a start state A tape that is infinite in both directions, containing finitely many non-blank symbols A head which points at one position on the tape A set of transitions Basics Definition Computability Building programs Complexity Turing Completeness What Are Turing Machines? Each Turing machine consists of A finite set of symbols, including a special blank symbol () Bruce Merry Turing Machines If in state si and tape contains qj , write qk then move left/right and change to state sm A tape that is infinite in both directions, containing -

Python C/C++ Java Perl Ruby

Programming Languages Big Ideas for CS 251 • What is a PL? Theory of Programming Languages • Why are new PLs created? Principles of Programming Languages – What are they used for? – Why are there so many? • Why are certain PLs popular? • What goes into the design of a PL? CS251 Programming Languages – What features must/should it contain? Spring 2018, Lyn Turbak – What are the design dimensions? – What are design decisions that must be made? Department of Computer Science Wellesley College • Why should you take this course? What will you learn? Big ideas 2 PL is my passion! General Purpose PLs • First PL project in 1982 as intern at Xerox PARC Java Perl • Created visual PL for 1986 MIT Python masters thesis • 1994 MIT PhD on PL feature Fortran (synchronized lazy aggregates) ML JavaScript • 1996 – 2006: worked on types Racket as member of Church project Haskell • 1988 – 2008: Design Concepts in Programming Languages C/C++ Ruby • 2011 – current: lead TinkerBlocks research team at Wellesley • 2012 – current: member of App Inventor development team CommonLisp Big ideas 3 Big ideas 4 Domain Specific PLs Programming Languages: Mechanical View HTML A computer is a machine. Our aim is to make Excel CSS the machine perform some specifieD acEons. With some machines we might express our intenEons by Depressing keys, pushing OpenGL R buIons, rotaEng knobs, etc. For a computer, Matlab we construct a sequence of instrucEons (this LaTeX is a ``program'') anD present this sequence to IDL the machine. Swift PostScript! – Laurence Atkinson, Pascal Programming Big ideas 5 Big ideas 6 Programming Languages: LinguisEc View Religious Views The use of COBOL cripples the minD; its teaching shoulD, therefore, be A computer language … is a novel formal regarDeD as a criminal offense. -

Unusable for Programming

UNUSABLE FOR PROGRAMMING DANIEL TEMKIN Independent, New York, USA [email protected] 2017.xCoAx.org Lisbon Computation Communication Aesthetics & X Abstract Esolangs are programming languages designed for non-practical purposes, often as experiments, par- odies, or experiential art pieces. A common goal of esolangs is to achieve Turing Completeness: the capability of implementing algorithms of any Keywords complexity. They just go about getting to Turing Esolangs Completeness with an unusual and impractical set Programming languages of commands, or unexpected waysDraft of representing Code art code. However, there is a much smaller class of Oulipo esolangs that are entirely “Unusable for Program- Tangible Computing ming.” These languages explore the very boundary of what a programming language is; producing uns- table programs, or for which no programs can be written at all. This is a look at such languages and how they function (or fail to). Final 1. INTRODUCTION Esolangs (for “esoteric programming languages”) include languages built as thought experiments, jokes, parodies critical of language practices, and arte- facts from imagined alternate computer histories. The esolang Unlambda, for example, is both an esolang masterpiece and typical of the genre. Written by David Madore in 1999, Unlambda gives us a version of functional programming taken to its most extreme: functions can only be applied to other functions, returning more functions, all of them unnamed. It’s a cyberlinguistic puzzle intended as a challenge and an experiment at the extremes of a certain type of language design. The following is a program that calculates the Fibonacci sequence. The code is nearly opaque, with little indication of what it’s doing or how it works. -

Exotic Programming Languages

I. Babich, Master student V. Spivachuk, PHD in Phil., As. Prof., research advisor Khmelnytskyi National University EXOTIC PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES The word ―exotic‖ is defined by the Oxford dictionary as ―of a kind not ordinarily encountered‖. If that is so, what is meant by exotic programming languages? These are languages that are not used for commercial purposes or even for anything ―useful‖. This definition can be applied a little loosely and, hence, many different types of programming languages can be classified as ―exotic‖. So, after some consideration, I have included three types of languages as belonging to this category. Exotic programming languages include languages that are intentionally designed to be difficult to learn and program with. Such languages are often used to analyse the power of programming languages. They are known as esoteric programming languages. Some exotic languages, known as joke languages, are created for the sake of fun. And the third type includes non – English – based programming languages. The definition clearly mentions that these languages do not serve any practical purpose. Then what’s all the fuss about exotic programming languages? To understand their importance, we need to first understand what makes a programming language a programming language. The “Turing completeness” of programming languages A language qualifies as a programming language in the true sense only if it is ―Turing complete‖ [1, c. 4]. A language that is Turing complete can be used to represent any computable algorithm. Many of the so called languages are, in fact, not languages, in the true sense. Examples of tools that are not Turing complete and hence not languages in the strict sense include HTML, XML, JSON, etc. -

Proof Pearl: Proving a Simple Von Neumann Machine Turing Complete

Proof Pearl: Proving a Simple Von Neumann Machine Turing Complete J Strother Moore Dept. of Computer Science, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA [email protected] http://www.cs.utexas.edu Abstract. In this paper we sketch an ACL2-checked proof that a simple but unbounded Von Neumann machine model is Turing Complete, i.e., can do anything a Turing machine can do. The project formally revisits the roots of computer science. It requires re-familiarizing oneself with the definitive model of computation from the 1930s, dealing with a simple “modern” machine model, thinking carefully about the formal statement of an important theorem and the specification of both total and partial programs, writing a verifying compiler, including implementing an X86- like call/return protocol and implementing computed jumps, codifying a code proof strategy, and a little “creative” reasoning about the non- termination of two machines. Keywords: ACL2, Turing machine, Java Virtual Machine (JVM), ver- ifying compiler 1 Prelude I have often taught an undergraduate course at the University of Texas at Austin entitled A Formal Model of the Java Virtual Machine. In the course, students are taught how to model sophisticated computing engines and, to a lesser extent, how to prove theorems about such engines and their programs with the ACL2 theorem prover [5]. The course starts with a pedagogical (“toy”) JVM-like model which the students elaborate over the semester towards a more realistic model, which is then compared to an accurate JVM model[9]. The pedagogical model is called M1: a stack based machine providing a fixed number of registers (JVM’s “locals”), an unbounded operand stack, and an execute-only program providing the following bytecode instructions ILOAD, ISTORE, ICONST, IADD, ISUB, IMUL, IFEQ, GOTO, and HALT, with unbounded arithmetic. -

NCCU Programming Languages Concepts 程式語言

NCCU Programming Languages: Concepts & Principles 程式語言 Instructor: 資科系 陳恭副教授 Spring 2006 Lecture 1 Contacts • Instructor: Dr. Kung Chen – E-mail: [email protected] –Office: 大仁樓200210 – Office Hours: Tuesday: 11am-12am • Teaching assistants: 資科系研究生 – E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] –Office: 資科系程式語言與軟體方法實驗室 • Class web page: – http://www.cs.nccu.edu/~chenk/Courses/PL What shall we study? Don’t Get Confused by the Course Name 教哪個程式語言? C++? Java? C#? … No! A “principles” course aims to teach the underlying concepts behind all programming languages (Concept-driven). Course Pre-requisite • Required course for CS major (junior) – Implies that it’s not an easy course • Prerequisite – Experience in C programming – Experience in C++ or Java programming • Non-CS major students – Better talk to the instructor or be well-motivated Programming languages Programming languages you have used you’ve heard of • C, Java, C++, C#, • Lisp, … •Basic, … •… Programming Languages’ Tower of Babel • Why are there so many programming languages? "I speak Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to my horse." — Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) Why So Many Languages? • Application domains have distinctive (and conflicting) needs • Examples: – Scientific Computing: high performance – Business: report generation – Artificial intelligence: symbolic computation – Systems programming: low-level access – Real-time systems: timing constraints – Special purpose languages –… Why So Many Languages? (Cont’d) • Evolution: Our understanding of programming evolves, so do languages grow! • The advance of programming methods usually lead to new programming languages: – Structured programming • Pascal – Object-Oriented Programming • Simula 67, Smalltalk, C++ – Functional programming • Socio-economic factors – Proprietary interests, commercial advantage • Personal preference Different Programming Language Design Philosophies C Other languages If all you have is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail. -

Programming Paradigms Lecture

The Beauty and Joy of Computing Lecture #5 Programming Paradigms UC Berkeley EECS Guest Lecturer TA Peter Sujan CITRIS INVENTION LAB! 3D PRINTED GUNS! It provides prototyping resources Is gun control a fruitless effort? such as 3D printing, laser cutting, soldering stations, hand and power tools. We are opening the lab to a limited number of students, staff & faculty to work on outside projects. invent.citris-uc.org motherboard.vice.com/read/click-print-gun-the-inside-story-of-the-3d-printed-gun-movement-video Programming Paradigms Lecture . What are they? Most are Hybrids! . The Four Primary ones Functional Imperative Object-Oriented OOP Example: Skecthpad Declarative . Turing Completeness . Summary en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programming_paradigm What are Programming Paradigms? . “The concepts and abstractions used to represent the elements of a program (e.g., objects, functions, variables, constraints, etc.) and the steps that compose a computation (assignation, evaluation, continuations, data flows, etc.).” . Or, a way to classify the style of programming. snap.berkeley.edu Of 4 paradigms, how many can Snap! be? a) 1 (functional) b) 1 (not functional) c) 2 d) 3 e) 4 Most Languages Are Hybrids! . This makes it hard to teach to students, because most languages have facets of several paradigms! Called “Multi-paradigm” languages Scratch too! . It’s like giving someone a juice drink (with many fruit in it) and asking to taste just one fruit! en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_programming Functional Programming (review) . Computation is the evaluation of functions f(x)=(x+3)* x Plugging pipes together Each pipe, or function, has x exactly 1 output Functions can be input! . -

Strong Turing Completeness of Continuous Chemical Reaction

Strong Turing Completeness of Continuous Chemical Reaction Networks and Compilation of Mixed Analog-Digital Programs François Fages, Guillaume Le Guludec, Olivier Bournez, Amaury Pouly To cite this version: François Fages, Guillaume Le Guludec, Olivier Bournez, Amaury Pouly. Strong Turing Complete- ness of Continuous Chemical Reaction Networks and Compilation of Mixed Analog-Digital Programs. CMSB 2017 - 15th International Conference on Computational Methods in Systems Biology, Sep 2017, Darmstadt, Germany. pp.108-127. hal-01519828v3 HAL Id: hal-01519828 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01519828v3 Submitted on 29 Aug 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Strong Turing Completeness of Continuous Chemical Reaction Networks and Compilation of Mixed Analog-Digital Programs Fran¸coisFages1, Guillaume Le Guludec1;2, Olivier Bournez3, and Amaury Pouly4 1 Inria, Universit´eParis-Saclay, EP Lifeware, Palaiseau, France 2 Sup Telecom, Paris, France 3 LIX, CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France 4 Max Planck Institute for Computer Science, Saarbr¨ucken, Germany Abstract. When seeking to understand how computation is carried out in the cell to maintain itself in its environment, process signals and make decisions, the continuous nature of protein interaction processes forces us to consider also analog computation models and mixed analog-digital computation programs. -

On Turing Completeness, Or Why We Are So Many Ram´Oncasares Orcid: 0000-0003-4973-3128

www.ramoncasares.com 20171226 TC 1 On Turing Completeness, or Why We Are So Many Ram´onCasares orcid: 0000-0003-4973-3128 Why are we so many? Or, in other words, Why is our species so successful? The ultimate cause of our success as species is that we, Homo sapiens, are the first and the only Turing complete species. Turing completeness is the capacity of some hardware to compute by software whatever hardware can compute. To reach the answer, I propose to see evolution and computing from the problem solving point of view. Then, solving more prob- lems is evolutionarily better, computing is for solving problems, and software is much cheaper than hardware, resulting that Turing completeness is evolutionarily disruptive. This conclusion, together with the fact that we are the only Turing complete species, is the reason that explains why we are so many. Most of our unique cognitive characteristics as humans can be derived from being Turing complete, as for example our complete language and our problem solving creativity. Keywords: Turing completeness, problem solving, cognition, evolution, hardware and software. This is doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5631922.v2, version 20171226. ⃝c 2017 Ram´onCasares; licensed as cc-by. Any comments on it to [email protected] are welcome. www.ramoncasares.com 20171226 TC 2 On Turing Completeness, or Why We Are So Many x1 Introduction . 3 x1.1 Why are we so many? . 3 x1.2 Contents . 3 x2 Turing completeness . 5 x2.1 The Turing machine . 5 x2.2 Real computing . 6 x2.3 The universal Turing machine . -

Attention Is Turing Complete

Journal of Machine Learning Research 22 (2021) 1-35 Submitted 3/20; Revised 10/20; Published 3/21 Attention is Turing Complete Jorge P´erez [email protected] Department of Computer Science Universidad de Chile IMFD Chile Pablo Barcel´o [email protected] Institute for Mathematical and Computational Engineering School of Engineering, Faculty of Mathematics Universidad Cat´olica de Chile IMFD Chile Javier Marinkovic [email protected] Department of Computer Science Universidad de Chile IMFD Chile Editor: Luc de Raedt Abstract Alternatives to recurrent neural networks, in particular, architectures based on self-attention, are gaining momentum for processing input sequences. In spite of their relevance, the com- putational properties of such networks have not yet been fully explored. We study the computational power of the Transformer, one of the most paradigmatic architectures ex- emplifying self-attention. We show that the Transformer with hard-attention is Turing complete exclusively based on their capacity to compute and access internal dense repre- sentations of the data. Our study also reveals some minimal sets of elements needed to obtain this completeness result. Keywords: Transformers, Turing completeness, self-Attention, neural networks, arbi- trary precision 1. Introduction There is an increasing interest in designing neural network architectures capable of learning algorithms from examples (Graves et al., 2014; Grefenstette et al., 2015; Joulin and Mikolov, 2015; Kaiser and Sutskever, 2016; Kurach et al., 2016; Dehghani et al., 2018). A key requirement for any such an architecture is thus to have the capacity of implementing arbitrary algorithms, that is, to be Turing complete. Most of the networks proposed for learning algorithms are Turing complete simply by definition, as they can be seen as a control unit with access to an unbounded memory; as such, they are capable of simulating any Turing machine. -

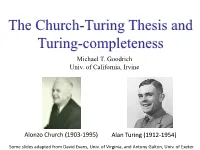

The Church-Turing Thesis and Turing-Completeness Michael T

The Church-Turing Thesis and Turing-completeness Michael T. Goodrich Univ. of California, Irvine Alonzo Church (1903-1995) Alan Turing (1912-1954) Some slides adapted from David Evans, Univ. of Virginia, and Antony Galton, Univ. of Exeter Recall: Turing Machine Definition . FSM Infinite tape: Γ* Tape head: read current square on tape, write into current square, move one square left or right FSM: Finite-state machine: transitions also include direction (left/right) final accepting and rejecting states 2 Types of Turing Machines • Decider/acceptor: w (input string) Turing Machine yes/no M • Transducer (more general, computes a function): w (input string) Turing Machine y (output string) M 3 Church • Alonzo Church, 1936, “We … define the notion An unsolvable problem … of an effectively of elementary number calculable function of theory. positive integers by • Introduced recursive identifying it with the functions and l- notion of a recursive definable functions and function of positive proved these classes integers.” equivalent. 4 Turing • Alan Turing, 1936, On “The [Turing machine] computable numbers, computable numbers with an application to include all numbers the Entscheidungs- which could naturally problem. be regarded as • Introduced the idea of a computable.” Turing machine computable number 5 The Church-Turing Thesis “Every effectively calculable function can be computed by a Turing-machine transducer.” “Since a precise mathematical definition of the term effectively calculable (effectively decidable) has been wanting, we can take this thesis ... as a definition of it...” – Kleene, 1943. That is, for every definition of “effectively computable” functions that people have come up with so far, a Turing machine can compute all such such functions.