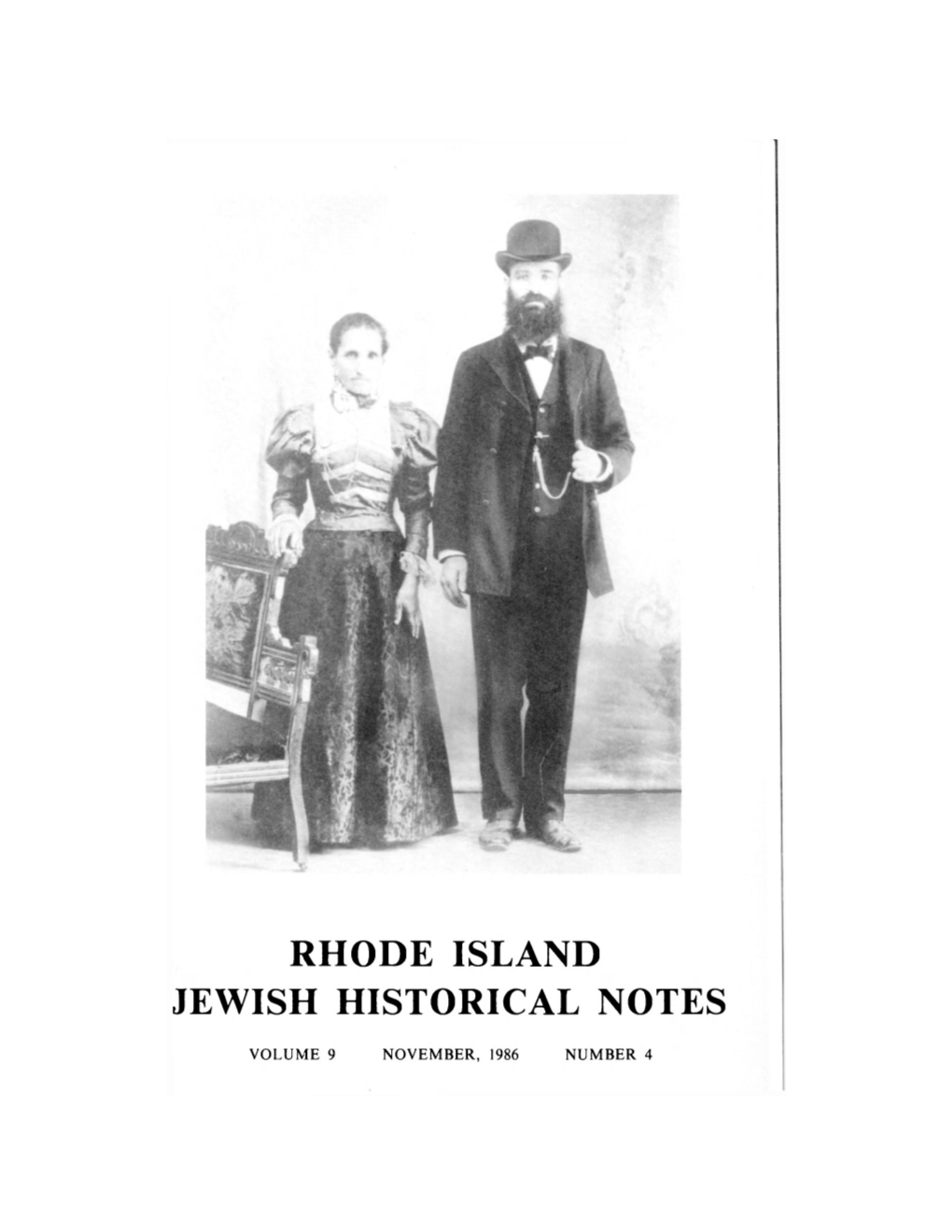

Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorr Rebellion

Rhode Island History Summer/Fall 2010 Volume 68, Number 2 Published by Contents The Rhode Island Historical Society 110 Benevolent Street Providence, Rhode Island 02906-3152 “The Rhode Island Question”: The Career of a Debate 47 Robert J. Manning, president William S. Simmons, first vice president Erik J. Chaput Barbara J. Thornton, second vice president Peter J. Miniati, treasurer Robert G. Flanders Jr., secretary Bernard P. Fishman, director No Landless Irish Need Apply: Rhode Island’s Role in the Framing and Fate Fellow of the Society of the Fifteenth Amendment 79 Glenn W. LaFantasie Patrick T. Conley Publications Committee Luther Spoehr, chair James Findlay Robert W. Hayman Index to Volume 68 91 Jane Lancaster J. Stanley Lemons Timothy More William McKenzie Woodward Staff Elizabeth C. Stevens, editor Hilliard Beller, copy editor Silvia Rees, publications assistant The Rhode Island Historical Society assumes no responsibility for the opinions of contributors. RHODE ISLAND HISTORY is published two times a year by the Rhode Island Historical Society at 110 Benevolent Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02906-3152. Postage is paid at Providence, Rhode Island. Society members receive each issue as a membership benefit. Institutional subscriptions to RHODE ISLAND HISTORY are $25.00 annually. Individual copies of current and back issues are available from the Society for $12.50 (price includes postage and handling). Manuscripts and other ©2010 by The Rhode Island Historical Society correspondence should be sent to Dr. Elizabeth C. Stevens, editor, at the RHODE ISLAND HISTORY (ISSN 0035-4619) Society or to [email protected]. Erik J. Chaput is a doctoral candidate in early American history at Syracuse Andrew Bourqe, Ashley Cataldo, and Elizabeth Pope, at the American University. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Citizens of God's Little Acre by Marjorie Drew

CITIZENS OF GOD’S LITTLE ACRE: THE LIVES AND LANDSCAPES OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN NEWPORT DURING THE COLONIAL ERA Marjorie Drew Master of Science, Historic Preservation School of Architecture, Art and Historic Preservation Roger Williams University August 2019 SIGNATURES Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Historic Preservation degree: Author: Marjorie Drew Date Thesis Advisor: Elaine B. Stiles Date Dean: Stephen White, AIA Date iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was made possible by the Community Partnerships Center at Roger Williams University, as well as the City of Newport Historic Cemetery Advisory Commission. This project combined my interest in history, as well as the preservation of cultural landscapes and how individuals contributed to the cultural landscape of Newport. Thank you to Lew Keen for presenting this project to the Community Partnership Center and for allowing me the pleasure to take on this special project. Thank you to Keith Stokes for providing me with valuable information and stories about those interred in God’s Little Acre Burial Ground. Your knowledge and passion for the burial ground and those interred is one of the reasons why the histories of those interred will be not be forgotten. Thank you to Professor Elaine Stiles for her guidance through this project. Working with a landscape that has changed over time and delivering histories of those long gone was a daunting undertaking, but with your guidance and perspective I was able to document how several citizens of God’s Little Acre contributed to the cultural landscape of Newport, Rhode Island. Thank you to Eileen O’Brien, Newport City Clerk for her guidance and expertise regarding land evidence records, probate documents and historic maps. -

Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Rhode Island History Special Collections 1885 Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Prescott O. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Prescott O., "Rhode Island and Providence Plantations" (1885). Rhode Island History. 19. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history/19 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rhode Island History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -RHODE ISLAND AND RHODE ISLAND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS. A SHORT HISTORICAL SKETCH AND STATISTICAL CoMPILATION BY PRESCOTT 0. CLARKE. TOGETHER WITH A Catalogue of the Rhode Island Exhibit AT THE NORTH, CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICAN EXPOSITION : CHARACTERISTICS, NEW ORLEANS, 1885-6. WILLIAM CARVER BATES, PRODUCTS. RHODE ISLAND COMMISSIONER. PROVIDENCE: E. A. JOHNSON & Co., PRINTERS. xss5• ,. 2 3 Rhode Island Horse Shoe Co.J •*lFJiE~ --,.->-,.MANUFACTURERS OF-y-<- 6RINNRL f\UTOMATIC ~PRINKLER '• --AND-- Horse, Mule~Snow Shoes, --AND-- FREDERICK GRINNELL, PROVIDENCE, R. 1., PATENTEE. TOE CALKS, Patented October 26th, 1881; Dec. 13th, 1881; Dec. 19th, 1.882; .iJfay 16th, 1883. --OF THE- - PEBKIHS Over 700 fstaolisnments are fquippea witn tnem, OFFICE AT Has Worked Successfully In 95 Cases of Actual Fire And Never Failed. ~;~, CLOSED. OPEN. The result of C. J. H. Woodbury's investigations of Automatic Sprinklers, made for the New England l\futual Immmnce Companies, shows that the Grinnell Sprinkler ili 1nore sen sitive to heat than :my other, and that it .-ustributes 'vatP.r n1ore effectively than any other Sensitive Sprinkler. -

John Brown's India Point by Caroline Frank Rhode Island History

John Brown's India Point By Caroline Frank Rhode Island History, Volume 61, Number 3 (November 2003), pp. 51-69. Digitally re-presented from .pdf available courtesy the RI Historical Society at: http://www.rihs.org/assetts/files/publications/2003_Fall.pdf Lying beneath Interstate 195 in Providence, just before it crosses the Seekonk River on the Washington Bridge, is a grassy half-mile strip of waterfront property. Other than an occasional jogger circling its neatly looped sidewalks, until recently few people visited this spot. Its abandoned gravel-and-mud ball fields and its rapidly silting-over shoreline seemed to announce just one more inner-city waterfront obituary. The space clung weakly to some idea of a park; yet it looked like the end of the line, literally and figuratively. Arriving from the north via Gano Street or from the west via India Street, directed by highway or street signs to pass under 1-195, expectant visitors reached India Point and found nowhere to go and no reason to stay. The shadow of the highway above and rotting, submerged pilings below were all that remotely linked this forgotten spot to glorious moments in its past as a major coastal transportation center. The property was virtually featureless. Roger Williams first paddled his boat around the rocky bluff of India Point in 1636. The initial intention among his small group of disaffected Puritans was to establish a settlement near this spot, across the Seekonk River from Plymouth Colony, but they found a more desirable location on the river to the west, around Foxes Hill (on Fox Point). -

Rhode Island's Shellfish Heritage

RHODE ISLAND’S SHELLFISH HERITAGE RHODE ISLAND’S SHELLFISH HERITAGE An Ecological History The shellfish in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s salt ponds have pro- vided humans with sustenance for over 2,000 years. Over time, shellfi sh have gained cultural significance, with their harvest becoming a family tradition and their shells ofered as tokens of appreciation and represent- ed as works of art. This book delves into the history of Rhode Island’s iconic oysters, qua- hogs, and all the well-known and lesser-known species in between. It of ers the perspectives of those who catch, grow, and sell shellfi sh, as well as of those who produce wampum, sculpture, and books with shell- fi sh"—"particularly quahogs"—"as their medium or inspiration. Rhode Island’s Shellfish Heritage: An Ecological History, written by Sarah Schumann (herself a razor clam harvester), grew out of the 2014 R.I. Shell- fi sh Management Plan, which was the first such plan created for the state under the auspices of the R.I. Department of Environmental Management and the R.I. Coastal Resources Management Council. Special thanks go to members of the Shellfi sh Management Plan team who contributed to the development of this book: David Beutel of the Coastal Resources Manage- Wampum necklace by Allen Hazard ment Council, Dale Leavitt of Roger Williams University, and Jef Mercer PHOTO BY ACACIA JOHNSON of the Department of Environmental Management. Production of this book was sponsored by the Coastal Resources Center and Rhode Island Sea Grant at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, and by the Coastal Institute at the University SCHUMANN of Rhode Island, with support from the Rhode Island Council for the Hu- manities, the Rhode Island Foundation, The Prospect Hill Foundation, BY SARAH SCHUMANN . -

Chronicles of Brunonia

Chronicles of Brunonia The Things They Planted Molly Jacobson Almost four hundred years ago, Roger Williams and his companions paddled down the Seekonk River and landed on the Rhode Island shore. Surrounded by wilderness, with no outside aid and scarce resources, these first settlers slowly raised their farms and homesteads, scavenged for food, and drafted laws for their community. http://dl.lib.brown.edu/cob Copyright © 2008 Molly Jacobson Written in partial fulfillment of requirements for E. Taylor’s EL18 or 118: “Tales of the Real World” in the Nonfiction Writing Program, Department of English, Brown University. Today, relics of the first European settlers of Rhode Island are buried mentally and physically by Providence. Asphalt runs over apple orchards Thomas Angell used to own. The Old State House presides over the western part of John Sweet’s fields. Waterman Street, which hugs Brown University, is the final legacy of the Englishman who lent it his name, while Brown’s English Department sits atop the northern end of his garden. The first Baptist Church in America straddles the original Francis Weston homestead. When these men and others left the Puritan settlement at Massachusetts in the early 1600s, they found immaculate countryside across the Seekonk River. Religious outcasts and enterprising colonists united to establish the Providence Plantations, laying ground for a singularly liberal colony. Today, historians herald them for their tolerance and independence. But these lofty ideals belie a more immediate human struggle. Before industry and new immigrants, the founders of Providence toiled dutifully by primitive farmhouses along the Seekonk to feed their families. -

Jonathan Edwards's Defense of Slavery Author(S): Kenneth P

Jonathan Edwards's Defense of Slavery Author(s): Kenneth P. Minkema Source: Massachusetts Historical Review, Vol. 4, Race & Slavery (2002), pp. 23-59 Published by: Massachusetts Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25081170 . Accessed: 12/09/2013 05:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Massachusetts Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Massachusetts Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.132.173.29 on Thu, 12 Sep 2013 05:14:28 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Edwards's Defense of Jonathan Slavery KENNETH P. MINKEMA On June 7, 1731, four men gathered around a table in a southern New England seaport, possibly at a tavern, to transact some busi ness. Three of them?one of advanced middle age, the other two about a decade younger, wearing fashionable suits and having by them on the table, or balanced on a crossed knee, fine hats?had the look of experi enced sailors. Beneath the coats of at least two of them could be seen what might, in the low light, have been the glint off of a sword hilt or the lock plate a of pistol.1 The fourth was an apparently fragile man in his late twenties, so thin as to look "emaciated, and impair'd in his Health."2 He was dressed in the wig, black suit, and Geneva tabs that he always made a point of wearing see in public. -

American Values Revisited

Fall 2012 Reflections Y A L E D I V I N I T Y S C H O O L Who Are We? American Values Revisited i There is an American sermon to deliver on the unholiness of pessimism. – Earl Shorris cover art “mournings After (september 11th)” by michael seri interior photography campaign buttons from past election seasons and social issue crusades Reflections wishes to thank tom strong of new Haven and John lindner of Yale Divinity school for allowing the use of their extensive election button collections. ReFlections – Volume 99, numbeR 2 issn 0362-0611 Reflections is a magazine of theological and ethical inquiry published biannually by Yale Divinity School. Opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent those of the sponsoring institution and its administration and faculty. We welcome letters to the editor. All correspondence regarding Reflections should be addressed to Ray Waddle at the School’s address or at [email protected]. For a free subscription or to buy additional copies of this issue, please go to www.yale.edu/reflections, or call 203.432.6550. Reflections study guides, summaries of back issues, and other information can be found on the website as well. Reflections readers are welcome to order additional compli- mentary copies of this and most past issues. The only cost is the actual shipping fee. To make a request, write to [email protected] Gregory E. Sterling – Publisher John Lindner – Editorial Director Ray Waddle – Editor-in-Chief Gustav Spohn – Managing Editor Constance Royster – Senior Advisor Peter W. -

Download Finding

PROVIDENCE PUBLIC LIBRARY Rhode Island Collection 029-02 James N. Arnold Collection Circa 1860-1935 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Number: 029-02 Title: James N. Arnold Collection Creator: Arnold, James N. (James Newell), 1844-1927 Dates: circa 1860-1935 Quantity: 29 boxes (total 24.8 linear feet), 1 oversized folder and 2 card catalogs ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Acquisition: The Arnold collection was transferred from Knight Memorial Library in November 2015. Accruals: No accruals are expected or accruals are expected Custodial history: James N. Arnold bequeathed his library and archival collection to the Elmwood Public Library Association, later named Knight Memorial Library, upon his death in 1927. During the years when Knight Memorial Library was a branch library of the Providence Public Library, the Arnold library of published materials was broken up and distributed amongst the library system. In 2015, the Knight Memorial Library gifted his archival materials to the Providence Public Library. Processed by: The collection was processed in 2016 by Britni C. Gorman & Kate Wells. Conservation: Not applicable Language: English RIGHTS AND ACCESS Access: This collection is open under the rules and regulations of the Providence Public Library, Rhode Island Collection department. Preferred Citation: Researchers are requested to use the following citation format: [item number], [item title], James N. Arnold Collection, Rhode Island Collection, Providence Public Library Property Rights: Copyright has been assigned to Providence Public Library. 029-02, James N. Arnold Collection 2 INFORMATION FOR RESEARCHERS Separated material None Published descrip. Not applicable Location of originals Not applicable Location of copies Not applicable Publication note Not applicable Subject headings Arnold Family Genealogy Connecticut--Genealogy Massachusetts--Genealogy Narragansett Indians Native Americans--History New Hampshire--Genealogy Rhode Island—Genealogy Rhode Island – History Rhode Island--History--Colonial period, ca. -

Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Rhode Island History Special Collections 1911 Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island Rhode Island Department of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Department of Education, Rhode Island, "Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island" (1911). Rhode Island History. 18. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rhode Island History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rhode Island Education Circulars HISTORICAL SERIES-V POINTS OF HISTORICAL INTEREST IN THE STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREPARED WITH THE CO-OPERATION OF THE Rhode Island Historical Society DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AFlCHIVEs Rhode Island Education Circulars rl HisTORICAL SERIEs-V /L'] I ' I\ l POINTS OF HISTORICAL INTEREST I N THE STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREPARED WITH THE CO- OPERATION OF THE Rhode Island Historical Society DEPARTMENT OF E DUCATION STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREFATORY NOTES. The pnmary object of the historical senes of the Rhode Island Education Circulars, the initial number of which was issued in 1908, is to supply the teachers and pupils of this state with important facts of Rhode Island history not generally found in text books and school libraries. For efficient civic training, it is essential that the children of our schools be taught the history and life of their own state. -

Captain Pierce's Fight: an Investigation Into a King Philip's War Battle Nda Its Remembrance and Memorialization Lawrence K

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 12-2011 Captain Pierce's Fight: An Investigation Into a King Philip's War Battle nda its Remembrance and Memorialization Lawrence K. LaCroix University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation LaCroix, Lawrence K., "Captain Pierce's Fight: An Investigation Into a King Philip's War Battle nda its Remembrance and Memorialization" (2011). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 69. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAPTAIN PIERCE’S FIGHT: AN INVESTIGATION INTO A KING PHILIP’S WAR BATTLE AND ITS REMEMBRANCE AND MEMORIALIZATION A Thesis Presented by LAWRENCE K. LaCROIX Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2011 Historical Archaeology Program © 2011 by Lawrence K. LaCroix All rights reserved CAPTAIN PIERCE’S FIGHT: AN INVESTIGATION INTO A KING PHILIP’S WAR BATTLE AND ITS REMEMBRANCE AND MEMORIALIZATION A Thesis Presented by LAWRENCE K. LaCROIX Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________________ Stephen A. Mrozowski, Professor Chairperson of Committee _________________________________________ Judith Francis Zeitlin, Professor Member _________________________________________ Heather B.