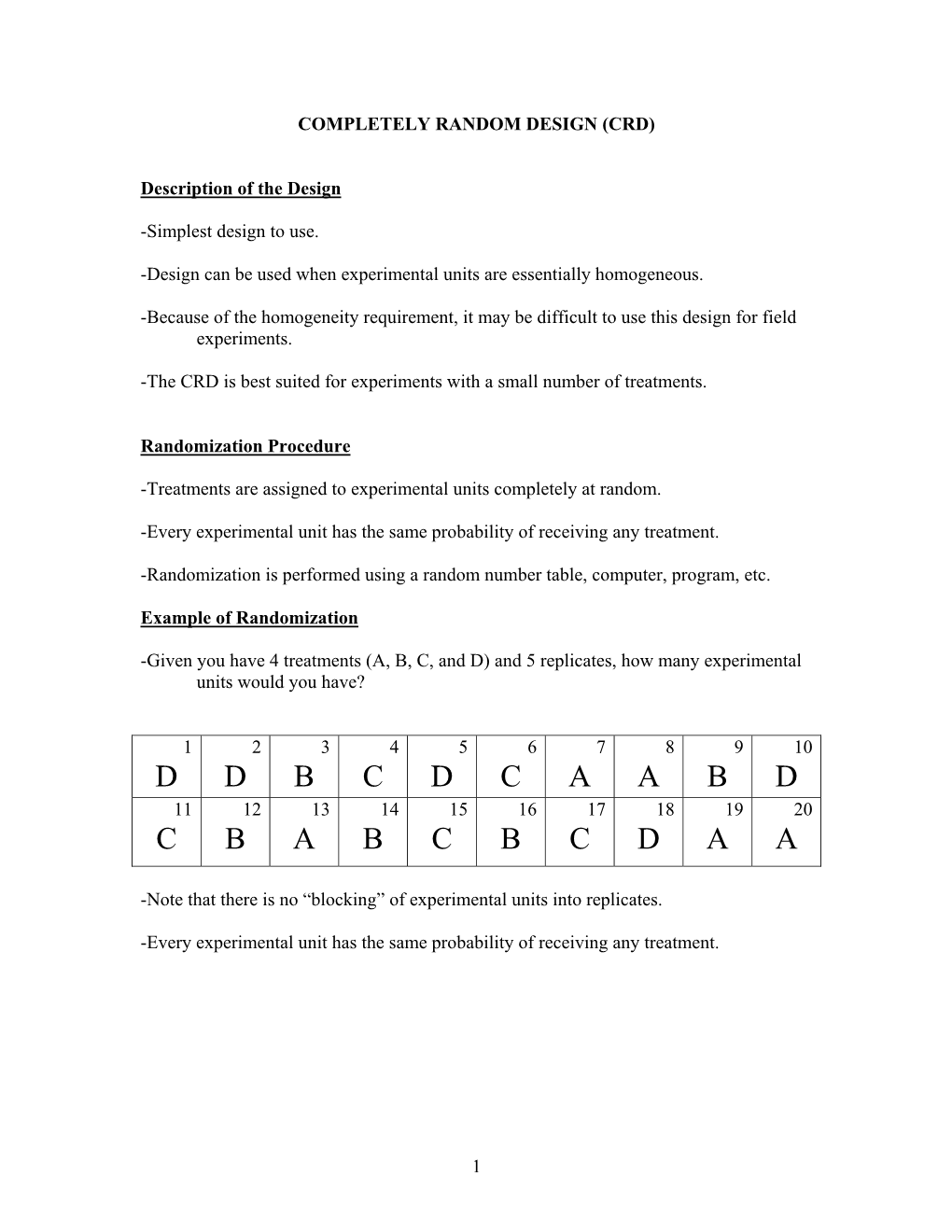

Completely Random Design (Crd)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Analysis 8: Two-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Statistical Analysis 8: Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) Research question type: Explaining a continuous variable with 2 categorical variables What kind of variables? Continuous (scale/interval/ratio) and 2 independent categorical variables (factors) Common Applications: Comparing means of a single variable at different levels of two conditions (factors) in scientific experiments. Example: The effective life (in hours) of batteries is compared by material type (1, 2 or 3) and operating temperature: Low (-10˚C), Medium (20˚C) or High (45˚C). Twelve batteries are randomly selected from each material type and are then randomly allocated to each temperature level. The resulting life of all 36 batteries is shown below: Table 1: Life (in hours) of batteries by material type and temperature Temperature (˚C) Low (-10˚C) Medium (20˚C) High (45˚C) 1 130, 155, 74, 180 34, 40, 80, 75 20, 70, 82, 58 2 150, 188, 159, 126 136, 122, 106, 115 25, 70, 58, 45 type Material 3 138, 110, 168, 160 174, 120, 150, 139 96, 104, 82, 60 Source: Montgomery (2001) Research question: Is there difference in mean life of the batteries for differing material type and operating temperature levels? In analysis of variance we compare the variability between the groups (how far apart are the means?) to the variability within the groups (how much natural variation is there in our measurements?). This is why it is called analysis of variance, abbreviated to ANOVA. This example has two factors (material type and temperature), each with 3 levels. Hypotheses: The 'null hypothesis' might be: H0: There is no difference in mean battery life for different combinations of material type and temperature level And an 'alternative hypothesis' might be: H1: There is a difference in mean battery life for different combinations of material type and temperature level If the alternative hypothesis is accepted, further analysis is performed to explore where the individual differences are. -

5. Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance

Sociology 740 John Fox Lecture Notes 5. Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance Copyright © 2014 by John Fox Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 1 1. Introduction I One of the limitations of multiple-regression analysis is that it accommo- dates only quantitative explanatory variables. I Dummy-variable regressors can be used to incorporate qualitative explanatory variables into a linear model, substantially expanding the range of application of regression analysis. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 2 2. Goals: I To show how dummy regessors can be used to represent the categories of a qualitative explanatory variable in a regression model. I To introduce the concept of interaction between explanatory variables, and to show how interactions can be incorporated into a regression model by forming interaction regressors. I To introduce the principle of marginality, which serves as a guide to constructing and testing terms in complex linear models. I To show how incremental I -testsareemployedtotesttermsindummy regression models. I To show how analysis-of-variance models can be handled using dummy variables. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 3 3. A Dichotomous Explanatory Variable I The simplest case: one dichotomous and one quantitative explanatory variable. I Assumptions: Relationships are additive — the partial effect of each explanatory • variable is the same regardless of the specific value at which the other explanatory variable is held constant. The other assumptions of the regression model hold. • I The motivation for including a qualitative explanatory variable is the same as for including an additional quantitative explanatory variable: to account more fully for the response variable, by making the errors • smaller; and to avoid a biased assessment of the impact of an explanatory variable, • as a consequence of omitting another explanatory variables that is relatedtoit. -

Analysis of Variance and Analysis of Variance and Design of Experiments of Experiments-I

Analysis of Variance and Design of Experimentseriments--II MODULE ––IVIV LECTURE - 19 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGNS AND THEIR ANALYSIS Dr. Shalabh Department of Mathematics and Statistics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur 2 Design of experiment means how to design an experiment in the sense that how the observations or measurements should be obtained to answer a qqyuery inavalid, efficient and economical way. The desigggning of experiment and the analysis of obtained data are inseparable. If the experiment is designed properly keeping in mind the question, then the data generated is valid and proper analysis of data provides the valid statistical inferences. If the experiment is not well designed, the validity of the statistical inferences is questionable and may be invalid. It is important to understand first the basic terminologies used in the experimental design. Experimental unit For conducting an experiment, the experimental material is divided into smaller parts and each part is referred to as experimental unit. The experimental unit is randomly assigned to a treatment. The phrase “randomly assigned” is very important in this definition. Experiment A way of getting an answer to a question which the experimenter wants to know. Treatment Different objects or procedures which are to be compared in an experiment are called treatments. Sampling unit The object that is measured in an experiment is called the sampling unit. This may be different from the experimental unit. 3 Factor A factor is a variable defining a categorization. A factor can be fixed or random in nature. • A factor is termed as fixed factor if all the levels of interest are included in the experiment. -

Understanding Replication of Experiments in Software Engineering: a Classification Omar S

Understanding replication of experiments in software engineering: A classification Omar S. Gómez a, , Natalia Juristo b,c, Sira Vegas b a Facultad de Matemáticas, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, 97119 Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico Facultad de Informática, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 28660 Boadilla del Monte, Madrid, Spain c Department of Information Processing Science, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland abstract Context: Replication plays an important role in experimental disciplines. There are still many uncertain-ties about how to proceed with replications of SE experiments. Should replicators reuse the baseline experiment materials? How much liaison should there be among the original and replicating experiment-ers, if any? What elements of the experimental configuration can be changed for the experiment to be considered a replication rather than a new experiment? Objective: To improve our understanding of SE experiment replication, in this work we propose a classi-fication which is intend to provide experimenters with guidance about what types of replication they can perform. Method: The research approach followed is structured according to the following activities: (1) a litera-ture review of experiment replication in SE and in other disciplines, (2) identification of typical elements that compose an experimental configuration, (3) identification of different replications purposes and (4) development of a classification of experiment replications for SE. Results: We propose a classification of replications which provides experimenters in SE with guidance about what changes can they make in a replication and, based on these, what verification purposes such a replication can serve. The proposed classification helped to accommodate opposing views within a broader framework, it is capable of accounting for less similar replications to more similar ones regarding the baseline experiment. -

Comparison of Response Surface Designs in a Spherical Region

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Mathematical and Computational Sciences Vol:6, No:5, 2012 Comparison of Response Surface Designs in a Spherical Region Boonorm Chomtee, John J. Borkowski Abstract—The objective of the research is to study and compare Where X is the design matrix, p is the number of model response surface designs: Central composite designs (CCD), Box- parameters, N is the design size, σ 2 is the maximum of Behnken designs (BBD), Small composite designs (SCD), Hybrid max designs, and Uniform shell designs (USD) over sets of reduced models f′′(x)( X X )−1 f (x) approximated over the set of candidate when the design is in a spherical region for 3 and 4 design variables. points. The values of the two criteria were calculated using The two optimality criteria ( D and G ) are considered which larger Matlab software [1]. values imply a better design. The comparison of design optimality criteria of the response surface designs across the full second order B. Reduced Models model and sets of reduced models for 3 and 4 factors based on the The set of reduced models is consistent with the definition two criteria are presented. of weak heredity given in Chipman [2]. That is, (i) a quadratic 2 Keywords—design optimality criteria, reduced models, response xi term is in the model only if the xi term is also in the model surface design, spherical design region and (ii) an interaction xi x j term is in the model only if the xi or x or both terms are also in the model. -

THE ONE-SAMPLE Z TEST

10 THE ONE-SAMPLE z TEST Only the Lonely Difficulty Scale ☺ ☺ ☺ (not too hard—this is the first chapter of this kind, but youdistribute know more than enough to master it) or WHAT YOU WILL LEARN IN THIS CHAPTERpost, • Deciding when the z test for one sample is appropriate to use • Computing the observed z value • Interpreting the z value • Understandingcopy, what the z value means • Understanding what effect size is and how to interpret it not INTRODUCTION TO THE Do ONE-SAMPLE z TEST Lack of sleep can cause all kinds of problems, from grouchiness to fatigue and, in rare cases, even death. So, you can imagine health care professionals’ interest in seeing that their patients get enough sleep. This is especially the case for patients 186 Copyright ©2020 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Chapter 10 ■ The One-Sample z Test 187 who are ill and have a real need for the healing and rejuvenating qualities that sleep brings. Dr. Joseph Cappelleri and his colleagues looked at the sleep difficul- ties of patients with a particular illness, fibromyalgia, to evaluate the usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale as a measure of sleep problems. Although other analyses were completed, including one that compared a treat- ment group and a control group with one another, the important analysis (for our discussion) was the comparison of participants’ MOS scores with national MOS norms. Such a comparison between a sample’s mean score (the MOS score for par- ticipants in this study) and a population’s mean score (the norms) necessitates the use of a one-sample z test. -

How to Randomize?

TRANSLATING RESEARCH INTO ACTION How to Randomize? Roland Rathelot J-PAL Course Overview 1. What is Evaluation? 2. Outcomes, Impact, and Indicators 3. Why Randomize and Common Critiques 4. How to Randomize 5. Sampling and Sample Size 6. Threats and Analysis 7. Project from Start to Finish 8. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis and Scaling Up Lecture Overview • Unit and method of randomization • Real-world constraints • Revisiting unit and method • Variations on simple treatment-control Lecture Overview • Unit and method of randomization • Real-world constraints • Revisiting unit and method • Variations on simple treatment-control Unit of Randomization: Options 1. Randomizing at the individual level 2. Randomizing at the group level “Cluster Randomized Trial” • Which level to randomize? Unit of Randomization: Considerations • What unit does the program target for treatment? • What is the unit of analysis? Unit of Randomization: Individual? Unit of Randomization: Individual? Unit of Randomization: Clusters? Unit of Randomization: Class? Unit of Randomization: Class? Unit of Randomization: School? Unit of Randomization: School? How to Choose the Level • Nature of the Treatment – How is the intervention administered? – What is the catchment area of each “unit of intervention” – How wide is the potential impact? • Aggregation level of available data • Power requirements • Generally, best to randomize at the level at which the treatment is administered. Suppose an intervention targets health outcomes of children through info on hand-washing. What is the appropriate level of randomization? A. Child level 30% B. Household level 23% C. Classroom level D. School level 17% E. Village level 13% 10% F. Don’t know 7% A. B. C. D. -

Relationships Between Sleep Duration and Adolescent Depression: a Conceptual Replication

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Sleep Health Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2020 February 25. Published in final edited form as: Sleep Health. 2019 April ; 5(2): 175–179. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2018.12.003. Relationships between sleep duration and adolescent depression: a conceptual replication AT Berger1, KL Wahlstrom2, R Widome1 1Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, 1300 South 2nd St, Suite #300, Minneapolis, MN 55454 2Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development, 210D Burton Hall, College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455 Abstract Objective—Given the growing concern about research reproducibility, we conceptually replicated a previous analysis of the relationships between adolescent sleep and mental well-being, using a new dataset. Methods—We conceptually reproduced an earlier analysis (Sleep Health, June 2017) using baseline data from the START Study. START is a longitudinal research study designed to evaluate a natural experiment in delaying high school start times, examining the impact of sleep duration on weight change in adolescents. In both START and the previous study, school day bedtime, wake up time, and answers to a six-item depression subscale were self-reported using a survey administered during the school day. Logistic regression models were used to compute the association and 95% confidence intervals (CI) between the sleep variables (sleep duration, wake- up time and bed time) and a range of outcomes. Results—In both analyses, greater sleep duration was associated with lower odds (P < 0.0001) of all six indicators of depressive mood. -

ANALYSIS of VARIANCE and MISSING OBSERVATIONS in COMPLETELY RANDOMIZED, RANDOMIZED BLOCKS and LATIN SQUARE DESIGNS a Thesis

ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE AND MISSING OBSERVATIONS IN COMPLETELY RANDOMIZED, RANDOMIZED BLOCKS AND LATIN SQUARE DESIGNS A Thesis Presented to The Department of Mathematics Kansas State Teachers College, Emporia, Kansas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Kiritkumar K. Talati May 1972 c; , ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sincere thanks and gratitude is expressed to Dr. John Burger for his assistance, patience, and his prompt attention in all directions in preparing this paper. A special note of appreciation goes to Dr. Marion Emerson, Dr. Thomas Davis, Dr. George Poole, Dr. Darrell Wood, who rendered assistance in the research of this paper. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 A. Preliminary Consideration. • • • • • • • 1 B. Purpose and Assumptions of the Analysis of Variance • • • • • • • • •• 1 C. Analysis of Covariance • • • • • • • • • 2 D. Definitions. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ) E. Organization of Paper. • • • • • • • • • 4 II. COMPLETELY RANDOMIZED DESIGN • • • • • • • • 5 A. Description............... 5 B. Randomization. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 C. Problem and Computations •••••••• 6 D. Conclusion and Further Applications. •• 10 III. RANDOMIZED BLOCK DESIGN. • • • • • • • • • • 12 A. Description............... 12 B. Randomization. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1) C. Problem and Statistical Analysis • • • • 1) D. Efficiency of Randomized Block Design as Compared to Completely Randomized Design. • • • • • • • • • •• 20 E. Missing Observations • • • • • • • • •• 21 F. -

Randomized Experimentsexperiments Randomized Trials

Impact Evaluation RandomizedRandomized ExperimentsExperiments Randomized Trials How do researchers learn about counterfactual states of the world in practice? In many fields, and especially in medical research, evidence about counterfactuals is generated by randomized trials. In principle, randomized trials ensure that outcomes in the control group really do capture the counterfactual for a treatment group. 2 Randomization To answer causal questions, statisticians recommend a formal two-stage statistical model. In the first stage, a random sample of participants is selected from a defined population. In the second stage, this sample of participants is randomly assigned to treatment and comparison (control) conditions. 3 Population Randomization Sample Randomization Treatment Group Control Group 4 External & Internal Validity The purpose of the first-stage is to ensure that the results in the sample will represent the results in the population within a defined level of sampling error (external validity). The purpose of the second-stage is to ensure that the observed effect on the dependent variable is due to some aspect of the treatment rather than other confounding factors (internal validity). 5 Population Non-target group Target group Randomization Treatment group Comparison group 6 Two-Stage Randomized Trials In large samples, two-stage randomized trials ensure that: [Y1 | D =1]= [Y1 | D = 0] and [Y0 | D =1]= [Y0 | D = 0] • Thus, the estimator ˆ ˆ ˆ δ = [Y1 | D =1]-[Y0 | D = 0] • Consistently estimates ATE 7 One-Stage Randomized Trials Instead, if randomization takes place on a selected subpopulation –e.g., list of volunteers-, it only ensures: [Y0 | D =1] = [Y0 | D = 0] • And hence, the estimator ˆ ˆ ˆ δ = [Y1 | D =1]-[Y0 | D = 0] • Only estimates TOT Consistently 8 Randomized Trials Furthermore, even in idealized randomized designs, 1. -

Topics in Experimental Design

Ronald Christensen Professor of Statistics Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of New Mexico Copyright c 2016 Topics in Experimental Design Springer Preface This (non)book assumes that the reader is familiar with the basic ideas of experi- mental design and with linear models. I think most of the applied material should be accessible to people with MS courses in regression and ANOVA but I had no hesi- tation in using linear model theory, if I needed it, to discuss more technical aspects. Over the last several years I’ve been working on revisions to my books Analysis of Variance, Design, and Regression (ANREG); Plane Answers to Complex Ques- tions: The Theory of Linear Models (PA); and Advanced Linear Modeling (ALM). In each of these books there was material that no longer seemed sufficiently relevant to the themes of the book for me to retain. Most of that material related to Exper- imental Design. Additionally, due to Kempthorne’s (1952) book, many years ago I figured out p f designs and wrote a chapter explaining them for the very first edition of ALM, but it was never included in any of my books. I like all of this material and think it is worthwhile, so I have accumulated it here. (I’m not actually all that wild about the recovery of interblock information in BIBs.) A few years ago my friend Chris Nachtsheim came to Albuquerque and gave a wonderful talk on Definitive Screening Designs. Chapter 5 was inspired by that talk along with my longstanding desire to figure out what was going on with Placett- Burman designs. -

How to Do Random Allocation (Randomization) Jeehyoung Kim, MD, Wonshik Shin, MD

Special Report Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery 2014;6:103-109 • http://dx.doi.org/10.4055/cios.2014.6.1.103 How to Do Random Allocation (Randomization) Jeehyoung Kim, MD, Wonshik Shin, MD Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul Sacred Heart General Hospital, Seoul, Korea Purpose: To explain the concept and procedure of random allocation as used in a randomized controlled study. Methods: We explain the general concept of random allocation and demonstrate how to perform the procedure easily and how to report it in a paper. Keywords: Random allocation, Simple randomization, Block randomization, Stratified randomization Randomized controlled trials (RCT) are known as the best On the other hand, many researchers are still un- method to prove causality in spite of various limitations. familiar with how to do randomization, and it has been Random allocation is a technique that chooses individuals shown that there are problems in many studies with the for treatment groups and control groups entirely by chance accurate performance of the randomization and that some with no regard to the will of researchers or patients’ con- studies are reporting incorrect results. So, we will intro- dition and preference. This allows researchers to control duce the recommended way of using statistical methods all known and unknown factors that may affect results in for a randomized controlled study and show how to report treatment groups and control groups. the results properly. Allocation concealment is a technique used to pre- vent selection bias by concealing the allocation sequence CATEGORIES OF RANDOMIZATION from those assigning participants to intervention groups, until the moment of assignment.