Forest Governance and Institutional Structure: an Ignored Dimension Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Province of Nueva Vizcaya Municipality of Aritao

SUBASTA 2019 RURAL BANK OF BAYOMBONG, INC. BAYOMBONG, NUEVA VIZCAYA TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: Notice is hereby given that pursuant to the Revised Rules and Regulations governing the rural banks, as amended, particularly the last paragraph of Section 22 of the said rules regarding disposition of all assets acquired in settlement of loans, the Rural Bank of Bayombong, Inc., hereby announces that on May 15, 2019, June 19, 2019, July 17, 2019, August 22, 2019, September 18, 2019, October 16, 2019, November 20, 2019, December 18, 2019 between the hours of 8:30 in the morning and 3:00 in the afternoon in the premises of main building of the said Rural Bank of Bayombong, Inc. the following assets acquired will be sold for cash to the highest bidder by way of public auction sale to be conducted by the President/Gen. Manager, Mrs. Martha R. Ramos. All properties not sold during the first date of auction sale aforementioned shall be offered again at subsequent dates until properties shall have been disposed. PROVINCE OF NUEVA VIZCAYA MUNICIPALITY OF ARITAO LOCATION OF PROPERTY STARTING BID T-128359- 796 sq. m.- Residential Lot 645,135.84 Pariir, Comon, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-132217- 925 sq. m.- Residential Lot/Orchard 751,813.16 Pariir, Comon, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-142181- 761 sq. m.- Residential Lot 342,320.27 Pk. Namnama, Bone North, Aritao, NV. T-142521-33,667 sq. m.- Veg. Land 273,049.38 Canabuan, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-147044- 7,949 sq. m.- Riceland 357.934.88 Bayagung, Canarem, Aritao, N.V. -

The Philippines Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT final version December 11, 2001 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 The Ecosystem Profile 3 The Corridor Approach to Conservation 3 BACKGROUND 4 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT 5 Prioritization of Corridors Within the Hotspot 6 SYNOPSIS OF THREATS 11 Extractive Industries 11 Increased Population Density and Urban Sprawl 11 Conflicting Policies 12 Threats in Sierra Madre Corridor 12 Threats in Palawan Corridor 15 Threats in Eastern Mindanao Corridor 16 SYNOPSIS OF CURRENT INVESTMENTS 18 Multilateral Donors 18 Bilateral Donors 21 Major Nongovernmental Organizations 24 Government and Other Local Research Institutions 26 CEPF NICHE FOR INVESTMENT IN THE REGION 27 CEPF INVESTMENT STRATEGY AND PROGRAM FOCUS 28 Improve linkage between conservation investments to multiply and scale up benefits on a corridor scale in Sierra Madre, Eastern Mindanao and Palawan 29 Build civil society’s awareness of the myriad benefits of conserving corridors of biodiversity 30 Build capacity of civil society to advocate for better corridor and protected area management and against development harmful to conservation 30 Establish an emergency response mechanism to help save Critically Endangered species 31 SUSTAINABILITY 31 CONCLUSION 31 LIST OF ACRONYMS 32 2 INTRODUCTION The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is designed to better safeguard the world's threatened biodiversity hotspots in developing countries. It is a joint initiative of Conservation International (CI), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. CEPF provides financing to projects in biodiversity hotspots, areas with more than 60 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial species diversity in just 1.4 percent of its land surface. -

(0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines

ORIS Project (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines Joni T. Acay and Nikki Dyanne C. Realubit In cooperation with: Page | 0 ORIS Project CLP PROJECT ID (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines PROJECT LOCATION AND DURATION: Luzon Island, Philippines Provinces of Bataan, Quirino, Isabela and Cagayan August 2012-July 2014 PROJECT PARTNERS: ∗ Mabuwaya Foundation Inc., Cabagan, Isabela ∗ Department of Natural Sciences (DNS) and Department of Development Communication and Languages (DDCL), College of Development Communication and Arts & Sciences, ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY-Cabagan, ∗ Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP), Manila ∗ Community Environmental and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) Aparri, CENRO Alcala, Provincial Enviroment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) Cagayan ∗ Protected Area Superintendent (PASu) Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, CENRO Naguilian, PENRO Isabela ∗ PASu Quirino Protected Landscape, PENRO Quirino ∗ PASu Mariveles Watershed Forest Reserve, PENRO Bataan ∗ Municipalities of Baggao, Gonzaga, San Mariano, Diffun, Limay and Mariveles PROJECT AIM: Generate baseline information for the conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole. PROJECT TEAM: Joni Acay, Nikki Dyanne Realubit, Jerwin Baquiran, Machael Acob Volunteers: Vanessa Balacanao, Othniel Cammagay, Reymond Guttierez PROJECT ADDRESS: Mabuwaya Foundation, Inc. Office, CCVPED Building, ISU-Cabagan Campus, -

Sitecode Year Region Penro Cenro Province

***Data is based on submitted maps per region as of January 8, 2018. AREA IN SITECODE YEAR REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT TENURE HECTARES 11-020900-0001-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.05 Tukon Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0002-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.08 Chanarian Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0003-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 0.08 Raele Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0004-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Uyugan Itbud Lone District 0.16 Batanes General Comprehensive High School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0005-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Savidug Lone District 0.19 Savidug Barrio School (lot 2) Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0006-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Nakanmuan Lone District 0.20 Nakanmuan Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0007-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 Diptan Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0008-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 DepEd -

Consolidated List of Establishments – Conduct of Cles

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF ESTABLISHMENTS – CONDUCT OF CLES 1. Our Lady of Victories Academy (OLOVA) Amulung, Cagayan 2. Reta Drug Solano, Nueva Vizcaya 3. SCMC/SMCA/SATO SM Cauayan City 4. GQ Barbershop SM Cauayan City 5. Quantum SM Cauayan City 6. McDonald SM Cauayan City 7. Star Appliance Center SM Cauyan City 8. Expressions Martone Cauyan City 9. Watch Central SM Cauayan City 10. Dickies SM Cauayan City 11. Jollibee SM Cauayan City 12. Ideal Vision SM Cauayan City 13. Mendrez SM Cauayan City 14. Plains and prints SM Cauayan City 15. Memo Express SM Cauayan City 16. Sony Experia SM Cauayan City 17. Sports Zone SM Cauayan City 18. KFC Phils. SM Cauayan City 19. Payless Shoe Souref SM Cauyan City 20. Super Value Inc.(SM Supermarket) SM Cauyan City 21. Watson Cauyan City 22. Gadget @ Xtreme SM Cauyan City 23. Game Xtreme SM Cauyan City 24. Lets Face II Cauyan City 25. Cafe Isabela Cauayan City 26. Eye and Optics SM Cauayan City 27. Giordano SM Cauayan City 28. Unisilver Cabatuan, Isabela 29. NAILAHOLICS Cabatuan, Isabela 30. Greenwich Cauayan City 31. Cullbry Cauayan City 32. AHPI Cauyan City 33. LGU Reina Mercedes Reina Mercedes, Isabela 34. EGB Construction Corp. Ilagan City 35. Cauayan United Enterp & Construction Cauayan City 36. CVDC Ilagan City 37. RRJ and MR. LEE Ilagan City 38. Savers Appliance Depot Northstar Mall Ilagan city 39. Jeffmond Shoes Northstar Mall Ilagan city 40. B Club Boutique Northstar Mall Ilagan city 41. Pandayan Bookshop Inc. Northstar Mall Ilagan city 42. Bibbo Shoes Northstar Mall Ilagan city 43. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

Region Name of Laboratory Ii 4J Clinical & Diagnostic

REGION NAME OF LABORATORY II 4J CLINICAL & DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY II A.G.PADRE MD. FAMILY HEALTHCARE CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER II A.M. YUMENA GENERAL HOSPITAL INC. II ADCARE DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY II ADVENTIST HOSPITAL - SANTIAGO CITY, INC. II AGUAS MATERNITY AND GENERAL HOSPITAL II ALCALA MUNICIPAL HOSPITAL II ALFONSO PONCE ENRILE MEMORIAL DISTRICT HOSPITAL II AMAZING GRACE MEDICAL & DIAGNOSTIC SERVICES II APARRI PROVINCIAL HOSPITAL II APAYAO CAGAYAN MEDICAL CENTER, INC. II ASANIAS POLYCLINIC II BALLESTEROS DISTRICT HOSPITAL II BATANES GENERAL HOSPITAL II BEST DIAGNOSTIC CORPORATION II CABATUAN FAMILY HOSPITAL, INC. II CAGAYAN HEALTH DIAGNOSTIC CENTER INC. II CAGAYAN VALLEY MEDICAL CENTER II CALAYAN INFIRMARY II CALLANG GENERAL HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER, INC. II CAMP MELCHOR F. DELA CRUZ STATION HOSPITAL II CARAG MEDICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC II CARITAS HEALTH SHIELD, INC. - TUGUEGARAO II CARITAS HEALTH SHIELD, INC.-SANTIAGO BRANCH II CAUAYAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL II CAUAYAN FAMILY HOSPITAL SATELLITE CLINIC AND LABORATORY II CAUAYAN MEDICAL SPECIALISTS HOSPITAL II CHARLES W. SELBY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL, INC. II CITY DIAGNOSTIC AND LABORATORY II CITY HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY II CLI DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY II CLINICA BUCAG MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC II CORADO MEDICAL CLINIC AND HOSPITAL II DE VERA MEDICAL CENTER, INC. II DEMANO'S MEDICAL AND PEDIATRIC CLINIC II DIADI EMERGENCY HOSPITAL REGION NAME OF LABORATORY II DIAGNOSTIKA CLINICAL LABORATORY II DIFFUN DISTRICT HOSPITAL II DIFFUN MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE CLINICAL LABORATORY II DIVINE CARE DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY II DIVINE MERCY WELLNESS CENTER, INC. II DLB DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY II DR. DOMINGO S. DE LEON GENERAL HOSPITAL II DR. ESTER R. GARCIA MEDICAL CENTER, INC. II DR. RONALD P. GUZMAN MEDICAL CENTER, INC. -

Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/Mnaos Region 2

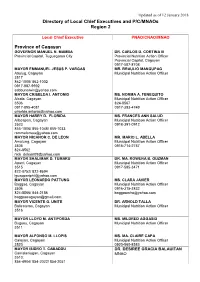

Updated as of 12 January 2018 Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/MNAOs Region 2 Local Chief Executive PNAO/CNAO/MNAO Province of Cagayan GOVERNOR MANUEL N. MAMBA DR. CARLOS D. CORTINA III Provincial Capitol, Tuguegarao City Provincial Nutrition Action Officer Provincial Capitol, Cagayan 0917-587-8708 MAYOR EMMANUEL JESUS P. VARGAS MR. BRAULIO MANGUPAG Abulug, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3517 862-1008/ 862-1002 0917-887-9992 [email protected] MAYOR CRISELDA I. ANTONIO MS. NORMA A. FENEQUITO Alcala, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 824-8567 0917-895-4081 0917-393-4749 [email protected] MAYOR HARRY D. FLORIDA MS. FRANCES ANN SALUD Allacapan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3523 0918-391-0912 855-1006/ 855-1048/ 855-1033 [email protected] MAYOR NICANOR C. DE LEON MR. MARIO L. ABELLA Amulung, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3505 0915-714-2757 824-8562 [email protected] MAYOR SHALIMAR D. TUMARU DR. MA. ROWENA B. GUZMAN Aparri, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3515 0917-585-3471 822-8752/ 822-8694 [email protected] MAYOR LEONARDO PATTUNG MS. CLARA JAVIER Baggao, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 0916-315-3832 824-8566/ 844-2186 [email protected] [email protected] MAYOR VICENTE G. UNITE DR. ARNOLD TALLA Ballesteros, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3516 MAYOR LLOYD M. ANTIPORDA MS. MILDRED AGGASID Buguey, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3511 MAYOR ALFONSO M. LLOPIS MS. MA. CLAIRE CAPA Calayan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3520 0920-560-8583 MAYOR ISIDRO T. CABADDU DR. DESIREE GRACIA BALAUITAN Camalaniugan, Cagayan MNAO 3510; 854-4904/ 854-2022/ 854-2051 Updated as of 12 January 2018 MAYOR CELIA T. -

COOPERATIVES ALL OVER the COUNTRY GOING the EXTRA MILE to SERVE THEIR MEMBERS and COMMUNITIES AMIDST COVID-19 PANDEMIC: REPORTS from REGION 2 #Coopagainstcovid19

COOPERATIVES ALL OVER THE COUNTRY GOING THE EXTRA MILE TO SERVE THEIR MEMBERS AND COMMUNITIES AMIDST COVID-19 PANDEMIC: REPORTS FROM REGION 2 #CoopAgainstCOVID19 COOPERATIVES IN ACTION Every business organization has a social responsibility (SR) to fulfill and cooperatives are of no exception. Social responsibility means that an organization should duly act on what benefits not just their business but also the environment and society as a whole. In times of crisis, the implementation of SR is tested. A business organization must choose between keeping the fund to sustain their business or spending this for causes that will benefit the society. The cooperative movement surely chose the latter. Although cooperatives were not required by the government to do community development activities, it is in their freewill that they extended assistance to the society in the hope of boosting the morale of the community even during the COVID – 19 pandemic. Below are some of the social responsibility activities of cooperatives in Region 2. MISSIONARIES OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION CREDIT COOPERATIVE in Alicia, Isabela provided financial assistance to their members, snacks for the frontliners, and relief goods for some residents in their barangay, as their way of showing their care for each other. ESPERANZA MPC in Aurora, Isabela conducted safety measures before distributing the PPEs. Page 1 of 5 CABAGAN DISTRICT CREDIT COOPERATIVE in Cabagan Isabela. Members & Officers of CDCC worked hand in hand in these trying times. Keeping the bayanihan spirit alive, the Cooperative distributed cash aid to its 352 coop members and gave relief goods to 25 family recipients within the 16 barangays in Cabagan, Isabela. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES

2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES 16,604 BASCO (Capital) 7,907 Ihubok II (Kayvaluganan) 2,103 Ihubok I (Kaychanarianan) 1,665 San Antonio 1,772 San Joaquin 392 Chanarian 334 Kayhuvokan 1,641 ITBAYAT 2,988 Raele 442 San Rafael (Idiang) 789 Santa Lucia (Kauhauhasan) 478 Santa Maria (Marapuy) 438 Santa Rosa (Kaynatuan) 841 IVANA 1,249 Radiwan 368 Salagao 319 San Vicente (Igang) 230 Tuhel (Pob.) 332 MAHATAO 1,583 Hanib 372 Kaumbakan 483 Panatayan 416 Uvoy (Pob.) 312 SABTANG 1,637 Chavayan 169 Malakdang (Pob.) 245 Nakanmuan 134 Savidug 190 Sinakan (Pob.) 552 Sumnanga 347 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population UYUGAN 1,240 Kayvaluganan (Pob.) 324 Imnajbu 159 Itbud 463 Kayuganan (Pob.) 294 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Cagayan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population CAGAYAN 1,124,773 ABULUG 30,675 Alinunu 1,269 Bagu 1,774 Banguian 1,778 Calog Norte 934 Calog Sur 2,309 Canayun 1,328 Centro (Pob.) 2,400 Dana-Ili 1,201 Guiddam 3,084 Libertad 3,219 Lucban 2,646 Pinili 683 Santa Filomena 1,053 Santo Tomas 884 Siguiran 1,258 Simayung 1,321 Sirit 792 San Agustin 771 San Julian 627 Santa -

Final Report

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES THE FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT FOR THE LOWER CAGAYAN RIVER IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT VOLUME III-2 SUPPORTING REPORT ANNEX VII WATERSHED MANAGEMENT ANNEX VIII LAND USE ANNEX IX COST ESTIMATE ANNEX X PROJECT EVALUATION ANNEX XI INSTITUTION ANNEX XII TRANSFER OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 2002 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. SSS JR 02- 07 List of Volumes Volume I : Executive Summary Volume II : Main Report Volume III-1 : Supporting Report Annex I : Socio-economy Annex II : Topography Annex III : Geology Annex IV : Meteo-hydrology Annex V : Environment Annex VI : Flood Control Volume III-2 : Supporting Report Annex VII : Watershed Management Annex VIII : Land Use Annex IX : Cost Estimate Annex X : Project Evaluation Annex XI : Institution Annex XII : Transfer of Technology Volume III-3 : Supporting Report Drawings Volume IV : Data Book The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of June 2001. The exchange rate is: US$1.00 = PHP50.0 = ¥120.0 Cagayan River N Basin PHILIPPINE SEA Babuyan Channel Apayao-Abulug ISIP Santa Ana Camalaniugan Dike LUZON SEA MabangucDike Aparri Agro-industry Development / Babuyan Channel by CEZA Catugan Dike Magapit PIS (CIADP) Lallo West PIP MINDANAO SEA Zinundungan IEP Lal-lo Dike Lal-lo KEY MAP Lasam Dike Evacuation System (FFWS, Magapit Gattaran Dike Alcala Amulung Nassiping PIP evacuation center), Resettlement, West PIP Dummon River Supporting Measures, CAGAYAN Reforestation, and Sabo Works Nassiping are also included in the Sto. Niño PIP Tupang Pared River Nassiping Dike Alcala Reviewed Master Plan.