Metatheater,' Aka 'Metadrama' Or 'Meta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fine Art of Lying: Disguise, Dissimulation, and Counterfeiting in Early Modern Culture”

The Fine Art of Lying in Early Modern English Drama Selected Papers from the IASEMS Graduate Conference “The Fine Art of Lying: Disguise, Dissimulation, and Counterfeiting in Early Modern Culture” The British Institute of Florence Florence, 7 April 2017 Edited by Angelica Vedelago and Kent Cartwright 1 2 THE BRITISH INSTITUTE OF FLORENCE THE ITALIAN ASSOCIATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN AND EARLY MODERN STUDIES 3 IASEMS Advisory Board Giuliana Iannaccaro, Università degli Studi di Milano Maria Luisa De Rinaldis, Università del Salento Gilberta Golinelli, Università di Bologna “Alma Mater Studiorum” Iolanda Plescia, Università di Roma “La Sapienza” Luca Baratta, Università degli Studi di Firenze 4 The Fine Art of Lying in Early Modern English Drama Selected Papers from the “The Fine Art of Lying: Disguise, Dissimulation, and Counterfeiting in Early Modern Culture” Graduate Conference Florence, 7 April 2017 Edited by Angelica Vedelago and Kent Cartwright The British Institute of Florence 2019 5 The Fine Art of Lying in Early Modern English Drama. Selected Papers from the “The Fine Art of Lying: Disguise, Dissimulation, and Counterfeiting in Early Modern Culture” Graduate Conference. Florence, 7 April 2017 / edited by Angelica Vedelago and Kent Cartwright – Firenze: The British Institute of Florence, 2019. © The Contributors, 2019 ISBN (online): 978-88-907244-9-7 https://www.britishinstitute.it/en/library/harold-acton-library/events-in-the-harold- acton-library Graphic design by Angelica Vedelago and Kent Cartwright Front cover: emblem of Henry Peacham, 1612, “Sapientiam, Avaritia, et Dolus, decipiunt”, in Minerua Britanna, Or a Garden of Heroical Deuises Furnished, and Adorned with Emblemes and Impresa's of Sundry Natures, Newly Devised, Moralized, and Published, by Henry Peacham, Mr. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

HAYDN À L'anglaise

HAYDN à l’anglaise NI6174 CAFO MOZART Caf€ Mozart Proprietor Derek McCulloch Emma Kirkby soprano Rogers Covey-Crump tenor Emma Kirkby soprano Rogers Covey-Crump tenor Jenny Thomas flute Ian Gammie guitar Alastair Ross square piano Jenny Thomas flute Ian Gammie guitar Alastair Ross square piano Derek McCulloch proprietor Instruments: Four-keyed flute: Rudolph Tutz, Innsbruck 2003, after August Grenser, c1790 Guitar: Nick Blishen, 2001; copy of Lacote, c1820 Square piano: William Southwell, London c1798. Restored by Andrew Lancaster, 2008 Tuning & maintenance: Edmund Pickering Tuning: a’=430; Vallotti Recorded June 7th-9th 2011 in Rycote Chapel nr Thame, Oxfordshire Sound engineer: Anthony Philpot. Producer: Dr Derek McCulloch Music edited and arranged by Ian Gammie & Derek McCulloch Source material: Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK Bodleian Libraries UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD © 2012 Caf€ Mozart Enterprises 64 Frances Rd Windsor SL4 3AJ [email protected] HAYDN à l’anglaise Cover picture: Derek McCulloch (©2012) after George Dance (1794) Haydn’s songs as edited by William Shield Graphics: Rod Lord (www.rodlord.com) ‘Ballads’ adapted from his instrumental music by Samuel Arnold Dedicated to the memory of Roy Thomas († February 2011) Rondos on his Canzonettas by Thomas Haigh Alastair Ross started his musical career as HAYDN à l’anglaise Organ Scholar in New College, Oxford in Caf€ Mozart Proprietor Derek McCulloch the 1960s. In the intervening years he has (a) Emma Kirkby soprano [1,2,3,6,8,10,14,15,17,19,20] established himself as one of the country’s (b) Rogers Covey-Crump tenor [1,2,4,7,9,10,11,13,14,15,18,19,20] foremost continuo players and as a solo (c) Jenny Thomas flute [2,7,8,9,10,13,14,15,19] harpsichordist with a particular affection for (d) Ian Gammie guitar [2,6,7,8,9,10,11,14,15,17,18,19,20] JS Bach. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Download (828Kb)

Original citation: Purcell, Stephen (2018) Are Shakespeare's plays always metatheatrical? Shakespeare Bulletin, 36 (1). pp. 19-35.doi:10.1353/shb.2018.0002 Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/97244 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: © 2018 The John Hopkins University Press. The article first appeared in Shakespeare Bulletin, 36 (1). pp. 19-35. March, 2018. A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRAP URL’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Are Shakespeare’s plays always metatheatrical? STEPHEN PURCELL University of Warwick The ambiguity of the term “metatheatre” derives in part from its text of origin, Lionel Abel’s 1963 book of the same name. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Trent 91; First Steps Towards a Stylistic Classification (Revised 2019 Version of My 2003 Paper, Originally Circulated to Just a Dozen Specialists)

Trent 91; first steps towards a stylistic classification (revised 2019 version of my 2003 paper, originally circulated to just a dozen specialists). Probably unreadable in a single sitting but useful as a reference guide, the original has been modified in some wording, by mention of three new-ish concordances and by correction of quite a few errors. There is also now a Trent 91 edition index on pp. 69-72. [Type the company name] Musical examples have been imported from the older version. These have been left as they are apart from the Appendix I and II examples, which have been corrected. [Type the document Additional information (and also errata) found since publication date: 1. The Pange lingua setting no. 1330 (cited on p. 29) has a concordance in Wr2016 f. 108r, whereti it is tle]textless. (This manuscript is sometimes referred to by its new shelf number Warsaw 5892). The concordance - I believe – was first noted by Tom Ward (see The Polyphonic Office Hymn[T 1y4p0e0 t-h15e2 d0o, cpu. m21e6n,t se suttbtinigt lneo] . 466). 2. Page 43 footnote 77: the fragmentary concordance for the Urbs beata setting no. 1343 in the Weitra fragment has now been described and illustrated fully in Zapke, S. & Wright, P. ‘The Weitra Fragment: A Central Source of Late Medieval Polyphony’ in Music & Letters 96 no. 3 (2015), pp. 232-343. 3. The Introit group subgroup ‘I’ discussed on p. 34 and the Sequences discussed on pp. 7-12 were originally published in the Ex Codicis pilot booklet of 2003, and this has now been replaced with nos 148-159 of the Trent 91 edition. -

Melodrama and Metatheatre: Theatricality in the Nineteenth Century Theatre

Spring 1997 85 Melodrama and Metatheatre: Theatricality in the Nineteenth Century Theatre Katherine Newey Metatheatricality has always been an important feature of the English theatre.1 In the case of melodrama on the nineteenth century popular stage, the genre as a whole is strongly marked by a metatheatrical awareness, and the self- referential nature of melodrama is one of its key modes of communication. The highly coded conventions of melodrama performance, with its over-determined practices of characterisation, acting, and staging, constitute a self-referential sign system which exploits the playfulness and artfulness of the theatre to a high degree. Such artfulness assumes that the spectator understands and accepts these codes and conventions, not simply as theatrical ploys, but as an approach to theatrical representation which is deliberately self-conscious and self-reflexive. Clearly, these theatrical practices extend the significance of metatheatricality beyond just those plays which fit easily into the obvious metatheatrical categories such as the play within the play, the framed play, or the play about the theatrical profession.2 It is the argument of this essay that what is melodramatic is also metatheatrical; that metatheatricality in melodrama is a result of the extremity of expression in character and structure which is established by nineteenth century melodrama. Metatheatrical plays of the popular stage challenge the usual distinctions made between high and popular culture, both in the nineteenth century and now. Metatheatrical theatre has generally been seen as a part of high culture, not popular culture. Discussions of metatheatricality in nineteenth century popular theatre either express surprise at its 'modernity,'3 or dismiss its existence at all.4 The self-consciousness and self-reflexivity of theatre which refers to itself, to its making or performing, or to its dramatic and theatrical illusions, is regarded as essentially literary: complex, and aesthetically informed. -

Life Is a Dream I.Fdx

Life is a Dream: A New Vintage Magical Realism Adaptation by Calderon Adapted by Annie R. Such Annie R. Such [email protected] www.arsplays.com 917.474.4850 CHARACTER NAME BRIEF DESCRIPTION AGE GENDER ACT I We hear whispers echoed as if in a cave. The lights come up on Segismundo sleeping in his cell held by chains and lit by a tine lamp. He is dressed in rags and animal skins. The whispers become clear bible verses, studies of the universe, all seem to swirl around the man. As the scene mounts, the whispers beckon him “Wake Up, Wake Up, Wake Up” HIGH ON A MOUNTAIN. THE WIND HOWLS AS THE SUN SETS. ROSAURA, DRESSED IN MALE SAILING ATTIRE, COMES UP FROM BEHIND THE BACK OF THE MOUNTAIN. ROSAURA Damn You, Poland. You give an ill welcome to a foreigner. Your blood stained sands mark an unwanted entrance into your lands. Don’t you know how long I’ve traveled, how far I’ve come? Hardly have I voyaged without struggles and torment- ‘Tis in my blood. But when have the unfortunate ever been delivered mercy? Clarin, Rosaura’s servant, comes around the mountain, panting heavily, carrying luggage like a pack mule. CLARIN Don’t speak for me, Lady-- as a lackey on your revenge quest, I should resent being added to your anguish, but not your speech to the stars. ROSAURA I refrained from giving you a share in my laments, Clarin, so as not to deprive you of your own soliloquy, your own philosophical answer to a rhetorical whine. -

Of Audiotape

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. DAVID N. BAKER NEA Jazz Master (2000) Interviewee: David Baker (December 21, 1931 – March 26, 2016) Interviewer: Lida Baker with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 19, 20, and 21, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 163 pp. Lida: This is Monday morning, June 19th, 2000. This is tape number one of the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project interview with David Baker. The interview is being conducted in Bloomington, Indiana, [in] Mr. Baker’s home. Let’s start with when and where you were born. David: [I was] born in Indianapolis, December 21st, 1931, on the east side, where I spent almost all my – when I lived in Indianapolis, most of my childhood life on the east side. I was born in 24th and Arsenal, which is near Douglas Park and near where many of the jazz musicians lived. The Montgomerys lived on that side of town. Freddie Hubbard, much later, on that side of town. And Russell Webster, who would be a local celebrity and wonderful player. [He] used to be a babysitter for us, even though he was not that much older. Gene Fowlkes also lived in that same block on 24th and Arsenal. Then we moved to various other places on the east side of Indianapolis, almost always never more than a block or two blocks away from where we had just moved, simply because families pretty much stayed on the same side of town; and if they moved, it was maybe to a larger place, or because the rent was more exorbitant, or something. -

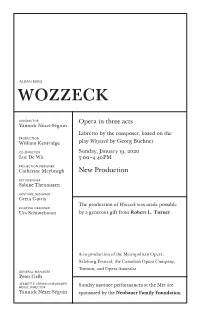

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

Metatheatre in Aeschylus' Oresteia

Athens Journal of Philology - Volume 2, Issue 1 – Pages 9-20 Metatheatre in Aeschylus’ Oresteia By Robert Lewis Smith Lionel Abel coined the word ‗metatheatre‘ in his 1963 book, Metatheatre: A New View of Dramatic Form, claiming he had discovered a new type of theatre, and cited Shakespeare‘s Hamlet as the first metatheatrical play. Over the intervening decades, various scholars have pushed the incidence of the earliest metatheatrical play back beyond Hamlet. Richard Hornby, in his 1986 book, Drama, Metadrama, and Perception, found instances of metatheatrical elements in many plays before Shakespeare and likewise found it in the theatre of other cultures. Despite that, he did not accept classical drama as being ‗fully‘ metatheatrical. However, Hornby provided the fullest taxonomy of metatheatrical characteristics: ceremony within the play, literary and real-life reference, role playing within the role, play within the play, and self- reference. Since then, Old Comedy has been accepted as fully metatheatrical, primarily because of the inclusion of the parabasis. For many, Greek tragedies have not been accepted as fully metatheatrical. An earlier paper by the author advanced the claim that Euripides‘ Medea was a metatheatrical play. Now a point-by- point comparison with Hornby‘s metatheatre taxonomy and Aeschylus‘ Oresteia posits that the Oresteia is also a fully metatheatrical play. The conclusion is that each day‘s plays by the tragic playwrights at Athens‘s City Dionysia, particularly with the inclusion of the satyr play, makes those plays fully metatheatrical. Hence, we should accept that metatheatricalism is a characteristic of all drama, not just of plays from a particular period.