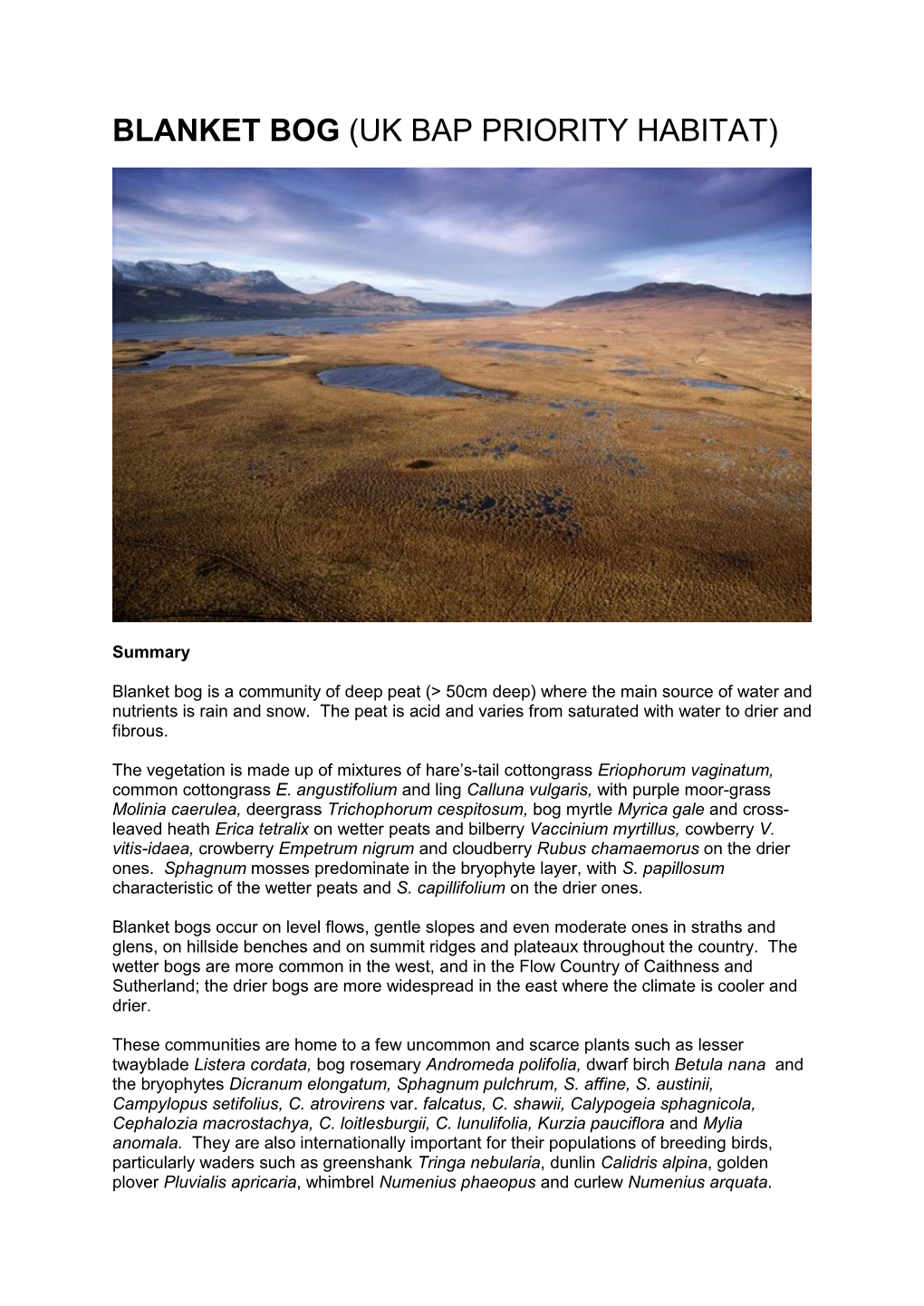

Blanket Bog (Uk Bap Priority Habitat)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Turbines, Sensitive Bird Populations and Peat Soils

Charity No. 229 325 Wind Turbines, Sensitive Bird Populations and Peat Soils: A Spatial Planning Guide for on-shore wind farm developments in Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside. July 2008 For more details, contact Tim Youngs [email protected] or Steve White [email protected] Produced by the RSPB and The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside (LWT), in partnership with Lancashire County Council, Natural England and the Merseyside Environmental Advisory Service (EAS) 1 Contents Section Map Annex Page Background 2 How to use the alert maps 4 Introduction 4 Key findings 5 Maps showing ‘important populations’ of ‘sensitive bird 1-5 6- 10 species’ and deep peat sensitive areas in Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside Legal protection for birds and habitats 11 Methodology and definitions 12- 15 Caveats and notes 16 Distribution of Whooper Swan, Bewick’s Swan and Pink- 17- 22 footed Goose in inland areas of Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside Thresholds for ‘important’ populations’ (of sensitive species) 1 23 Definition of terms relating to ‘sensitive species’ of bird 2 24 Background The Inspectors who carried out the Examination in Public of the draft NW Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) between December 06 to February 07, proposed that 'Maps of broad areas where the development of particular types of renewable energy may be considered appropriate should be produced as a matter of urgency and incorporated into an early review of RSS'. This proposal underpins the North West Regional Assembly’s (NWRA) research that is being carried out by Arup consultants. The Secretary of State's response is 'In line with PPS22, we consider that an evidence-based map of broad locations for installation of renewable energy technologies would benefit planning authorities and developers. -

Tag Der Artenvielfalt 2018 in Weißbrunn, Ulten (Gemeinde Ulten, Südtirol, Italien)

Thomas Wilhalm Tag der Artenvielfalt 2018 in Weißbrunn, Ulten (Gemeinde Ulten, Südtirol, Italien) Keywords: species diversity, Abstract new records, Ulten, Val d’Ultimo, South Tyrol, Italy Biodiversity Day 2018 in Weißbrunn, Ulten Valley (municipality of Ultimo, South Tyrol, Italy) The 19 th Biodiversity Day in South Tyrol was held in the municipality of Ulten/Ultimo. A total of 886 taxa were found. Einleitung Der 19. Südtiroler Tag der Artenvielfalt wurde am 30. Juni 2018 im Talschluss von Ulten abgehalten. Wie in den Jahren zuvor oblag dem Naturmuseum Südtirol sowohl die Organisation im Vorfeld als auch die Koordination vor Ort. Begleitend zu den Felderhebungen der zahlreichen Fachleute (siehe einzelne Beiträge) war ein didakti- sches Rahmenprogramm vorgesehen, das eine vogelkundliche und eine naturkundliche Wanderung im Untersuchungsgebiet (Organisation: Nationalpark Stilfserjoch unter der Koordination von Ronald Oberhofer) sowie ein Kinder- und Familienprogramm im Nationalparkhaus Lahnersäge in St. Gertraud umfasste (Organisation und Durchführung durch die Mitarbeiterinnen des Naturmuseums Südtirol Johanna Platzgummer, Elisabeth Waldner und Verena Preyer). Für allgemeine Informationen (Konzept und Organisation) zum Tag der Artenvielfalt und insbesondere zur Südtiroler Ausgabe siehe HILPOLD & KRANEBITTER (2005) und SCHATZ (2016). Adresse der Autors: Thomas Wilhalm Naturmuseum Südtirol Bindergasse 1 I-39100 Bozen thomas.wilhalm@ naturmuseum.it DOI: 10.5281/ zenodo.3565390 Gredleriana | vol. 19/2019 247 | Untersuchungsgebiet Das Untersuchungsgebiet umfasste in seinem Kern die Flur „Weißbrunn“ im Talschluss von Ulten westlich der Ortschaft St. Gertraud, d.h. den Bereich zwischen dem Weißbrunnsee (Stausee) und der Mittleren Weißbrunnalm. Im Süden war das Gebiet begrenzt durch die Linie Fischersee-Fiechtalm-Lovesboden, im Nordwesten durch den Steig Nr. 12 östlich bis zur Hinteren Pilsbergalm. -

Questioning Ten Common Assumptions About Peatlands

Questioning ten common assumptions about peatlands University of Leeds Peat Club: K.L. Bacon1, A.J. Baird1, A. Blundell1, M-A. Bourgault1,2, P.J. Chapman1, G. Dargie1, G.P. Dooling1,3, C. Gee1, J. Holden1, T. Kelly1, K.A. McKendrick-Smith1, P.J. Morris1, A. Noble1, S.M. Palmer1, A. Quillet1,3, G.T. Swindles1, E.J. Watson1 and D.M. Young1 1water@leeds, School of Geography, University of Leeds, UK 2current address: Centre GEOTOP, CP 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, Québec, Canada 3current address: Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, UK _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Peatlands have been widely studied in terms of their ecohydrology, carbon dynamics, ecosystem services and palaeoenvironmental archives. However, several assumptions are frequently made about peatlands in the academic literature, practitioner reports and the popular media which are either ambiguous or in some cases incorrect. Here we discuss the following ten common assumptions about peatlands: 1. the northern peatland carbon store will shrink under a warming climate; 2. peatlands are fragile ecosystems; 3. wet peatlands have greater rates of net carbon accumulation; 4. different rules apply to tropical peatlands; 5. peat is a single soil type; 6. peatlands behave like sponges; 7. Sphagnum is the main ‘ecosystem engineer’ in peatlands; 8. a single core provides a representative palaeo-archive from a peatland; 9. water-table reconstructions from peatlands provide direct records of past climate change; and 10. restoration of peatlands results in the re-establishment of their carbon sink function. In each case we consider the evidence supporting the assumption and, where appropriate, identify its shortcomings or ways in which it may be misleading. -

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate change Main Report Published By Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur & Wetlands International, Wageningen First Published in Electronic Format in December 2007 This version first published in May 2008 Copyright © 2008 Global Environment Centre & Wetlands International Reproduction of material from the publication for educational and non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from Global Environment Centre or Wetlands International, provided acknowledgement is provided. Reference Parish, F., Sirin, A., Charman, D., Joosten, H., Minayeva , T., Silvius, M. and Stringer, L. (Eds.) 2008. Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report . Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur and Wetlands International, Wageningen. Reviewer of Executive Summary Dicky Clymo Available from Global Environment Centre 2nd Floor Wisma Hing, 78 Jalan SS2/72, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Tel: +603 7957 2007, Fax: +603 7957 7003. Web: www.gecnet.info ; www.peat-portal.net Email: [email protected] Wetlands International PO Box 471 AL, Wageningen 6700 The Netherlands Tel: +31 317 478861 Fax: +31 317 478850 Web: www.wetlands.org ; www.peatlands.ru ISBN 978-983-43751-0-2 Supported By United Nations Environment Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNEP/GEF) with assistance from the Asia Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) Design by Regina Cheah and Andrey Sirin Printed on Cyclus 100% Recycled Paper. Printing on recycled paper helps save our natural -

Blanket Bogs

SCOTTISH INVERTEBRATE HABITAT MANAGEMENT Blanket bogs Claish Moss © Scottish Natural Heritage Introduction that may also provide important sub-habitats. Britain has about 10-15% of the total global area Invertebrates in upland moorland or bog habitats of blanket bog, making it one of the most are an essential component of the diet of many important international locations for this habitat. bird species; cranefly larvae and adults have 80-85% of Britain’s blanket bog habitat is found in been shown to be important food for grouse Scotland, covering 1.8 million hectares, and chicks and breeding waders, such as Golden representing 23% of the country’s land area. This plover. Adult grouse may also eat craneflies to makes Scotland an internationally important supplement their diet of heather shoots. country for blanket bog. Managing habitats to benefit these invertebrates Blanket bog is found in cool, wet, typically is thus likely to have a significant impact on the oceanic climates, where it can cover whole survival of upland birds. landscapes, such as in the North-West of In addition, the Scottish Invertebrate Species Scotland. Peat accumulates slowly over many Knowledge Dossiers: Pseudoscorpiones years and can reach depths exceeding 5m, indicated the possibility that the Bog chelifer although 0.5-3m is more typical. Blanket bog is (Microbisium brevifemoratum ) is likely to occur in “ombrotrophic”, that is, the water and mineral Scottish bogs—highlighting that there may yet be supply comes entirely from atmospheric sources unrecorded species in this important Scottish (rainwater, mist, cloud-cover). The water habitat (Legg, 2010). chemistry is nutrient-poor and acidic and the Support for management described in this habitat is dominated by acid-loving plant document is available through Scotland Rural communities, especially Sphagnum mosses. -

Peat from Penguins to Palm Trees

Organic Soils in the UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. Peat from Penguins to Palm Trees Janet Moxley [email protected] (CEH), Chris Evans (CEH), Nicole Archer (BGS), Mary-Ann Smyth (Crichton Carbon Centre) Introduction The UK has 14 Overseas Territories (OTs) and 3 Crown Dependencies (CDs). The Falkland Islands contain large areas of organic soils, with smaller areas in the Isle of Man and the Caribbean OTs. Where sufficient data are available GHG emissions from the OTs and CDs which have ratified or are likely to ratify the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol are included in the UK GHG inventory. We review current understanding of organic soils in these areas. The Falkland Islands Estimates of peat area vary between 282 kha (BGS and CEH, unpublished data) and 548 kha (Wilson et al, 1993). The BGS/CEH estimate assumes that all valley-bottom deposits, and 33% of upland organo-mineral soils on shallow slopes, are peat, based on new field survey data. Falkland peatlands comprise a mixture of upland blanket bog covered with Astelia pumila, White grass (Cortadelia pilosa), Diddle Dee (Empetrum rubrum), and white grass-dominated valley mire. Rainfall is low, resulting in only low presence of Sphagnum magellanicum, and (combined with high wind speeds) in high susceptibility to erosion. The main pressures are from grazing by large numbers of sheep, use of prescribed fire for vegetation management, dredging of stream channels to increase drainage, wildfires, effects of historic bomb craters, domestic peat extraction, and the use of turf banks as windbreaks. Peat distribution has been mapped, but peat condition has not been documented. -

Blanket Bog Toolkit

BLANKET Outcomes and BOG improvements LAND MANAGEMENT GUIDANCE CONTENTS Introduction 3 Introduction 3 How to use this pack 4 Blanket bog toolkit This guidance for land managers and conservation advisers has been collaboratively 7 State 2: Bare Peat produced by representatives of the Uplands Management Group (UMG) in response to a 11 State 3: Dwarf shrub dominated blanket bog request from the Uplands Stakeholder Forum (USF) for best practice guidance. 15 State 4: Grass and/or sedge dominated blanket bog 19 State 5: Modified blanket bog It is designed to put into practice the joint voluntary Defra Blanket Bog Restoration Strategy agreed by the Uplands Stakeholder Forum (USF). 23 State 6: Active hummock/hollow/ridge blanket bog This guidance will enable land managers to take steps to improve the vegetation characteristics and hydrological properties of blanket bog, which is defined by a peat depth of over 0.4m, across the uplands of England (see Q1–2). The five agreed outcomes (see Q5) sought by land managers and conservationists via this approach are: = the capture and storage of carbon = improved water quality and flow regulation = high levels of biodiversity = a healthy red grouse population = good quality grazing The UMG provides practitioner input to the USF, chaired by Defra. The Group seeks to produce guidance for practitioners covering a range of upland management activity. For more information go to: www.uplandsmanagement.co.uk HOW TO USE THIS PACK The guidance consists of: = DECISION MAKING TOOLKIT Use it out on the hill to agree the starting condition of the blanket bog and to decide on the best management methods to improve it. -

Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 128, the Habitats of Cutover Raised

ISSN 1393 – 6670 N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE THE HABITATS OF CUTOVER RAISED BOG George F. Smith & William Crowley I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 128 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) commissions a range of reports from external contractors to provide scientific evidence and advice to assist it in its duties. The Irish Wildlife Manuals series serves as a record of work carried out or commissioned by NPWS, and is one means by which it disseminates scientific information. Others include scientific publications in peer reviewed journals. The views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of NPWS and should, therefore, not be attributed to NPWS. Front cover, small photographs from top row: Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Garden Tiger Arctia caja, Brian Nelson; Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis, David Tierney; Common Newt Lissotriton vulgaris, Brian Nelson; Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris, Jenni Roche; Raised bog pool, Derrinea Bog, Co. Roscommon, Fernando Fernandez Valverde; Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson Main photograph: Round-leaved Sundew Drosera rotundifolia, Tina Claffey The habitats of cutover raised bog George F. Smith1 & William Crowley2 1Blackthorn Ecology, Moate, Co. Westmeath; 2The Living Bog LIFE Restoration Project, Mullingar, Co. Westmeath Keywords: raised bog, cutover bog, conservation, classification scheme, Sphagnum, cutover habitat, key, Special Area of Conservation, Habitats Directive Citation: Smith, G.F. -

Sphagnum Capillifolium Subsp

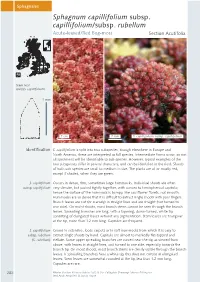

Sphagnales Sphagnum capillifolium subsp. capillifolium/subsp. rubellum Acute-leaved/Red Bog-moss Section Acutifolia Stem leaf (subsp. capillifolium) 1 mm 1 cm 2 mm S. capillifolium subsp. capillifolium Identification S. capillifolium is split into two subspecies, though elsewhere in Europe and North America, these are interpreted as full species. Intermediate forms occur, so not all specimens will be identifiable to sub-species. However, typical examples of the two subspecies differ in several characters, and can be identified in the field. Shoots of both sub-species are small to medium in size. The plants are all or mostly red, except if shaded, when they are green. S. capillifolium Occurs in dense, firm, sometimes large hummocks. Individual shoots are often subsp. capillifolium very slender, but packed tightly together, with convex to hemispherical capitula; hence the surface of the hummock is bumpy, like cauliflower florets, not smooth. Hummocks are so dense that it is difficult to extract single shoots with your fingers. Branch leaves are not (or scarcely) in straight lines and are straight (not turned to one side). On moist shoots, most branch stems cannot be seen through the branch leaves. Spreading branches are long, with a tapering, down-turned, white tip, consisting of elongated leaves without any pigmentation. Stem leaves are triangular at the tip, more than 1.2 mm long. Capsules are frequent. S. capillifolium Grows in extensive, loose carpets or in soft hummocks from which it is easy to subsp. rubellum extract single shoots by hand. Capitula are almost to markedly flat-topped and (S. rubellum) stellate. Some upper spreading branches are curved near the tip, as viewed from above, with leaves in straight lines, and turned to one side, especially towards the branch tip. -

Ecohydrological Characteristics of a Newly Identified Coastal Raised Bog on the Western Olympic Peninsula, Washington State, USA

Received: 3 September 2020 Revised: 12 December 2020 Accepted: 9 February 2021 DOI: 10.1002/eco.2287 RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecohydrological characteristics of a newly identified coastal raised bog on the western Olympic Peninsula, Washington State, USA F. Joseph Rocchio1 | Edward Gage2 | Tynan Ramm-Granberg1 | Andrea K. Borkenhagen2 | David J. Cooper2 1Washington Department of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program, Abstract Olympia, Washington, USA In western North America, ombrotrophic bogs are known to occur as far south as 2 Department of Forest and Rangeland coastal regions of British Columbia. A recent discovery of a peatland with a raised Stewardship, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA peat surface on the western Olympic Peninsula in Washington State (Crowberry Bog), USA, suggested that the distribution range of this ecosystem type extends fur- Correspondence F. Joseph Rocchio, Washington Department of ther south along the coast. To confirm if the site was an ombrotrophic peatland, we Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program, analysed its topography, hydrologic regime, water chemistry and vegetation. LiDAR Olympia, WA, USA Email: [email protected] data indicated that the peatland is elevated nearly 3 m above the surrounding land- scape. Water table variations in the plateau were strongly associated with seasonal Present address Andrea K. Borkenhagen, Advisian, Calgary, and daily precipitation events, indicating ombrotrophy. The hydraulic gradient on the Alberta, Canada. plateau is downward through most of the year, demonstrating that precipitation is percolating vertically into deeper peat layers. In the rand, the hydraulic gradients are horizontal over much of the year, indicating that the plateau is draining through the rand to the lagg. -

JNCC Guidelines for the Selection of Sssis

SUBJECT TO REVISION For further information see http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2303 Guidelines for the selection of biological SSSI’s Part 2: Detailed guidelines for habitats and species groups 8 BOGS To view other chapters of the guidelines visit : http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2303 SUBJECT TO REVISION For further information see http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2303 8 BOGS 1 Introduction 1.1 Ombrotrophic (rain-fed) mire, so called because its mineral nutrients are derived principally from rainfall rather than ground-water sources, is the other main class of peatland. In Britain these mires are termed bogs and in contrast to fens, which are fed by mineral-enriched waters, their vegetation is characterized by acidophilous upland communities in which the genus Sphagnum usually is, or has been, a conspicuous component. In the humid, oceanic climate of Britain, “ombrogenous” (= rain-generated) bogs are an especially important element of the original range of vegetation formations. They are an extensive feature of western and northern areas, where measurable rain falls on two days out of three. This regular input of precipitation produces a fairly constant level of surface seepage on many bogs, which gives rise to other distinctive communities which in Fennoscandia would be regarded as fen (minerotrophic mire) but in Britain are considered to be part of bog complexes. In lowland areas with predominantly acidic substrata there are examples of valley and basin mires which received acidic surface seepage giving rise to ombrotrophic vegetation similar to that of ombrogenous mire. These may be classifies as fen/bog complexes (see Chapter 7, section 4, NCC 1989). -

Small Patch Communities of Caribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park

Small Patch Communities of Caribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Lorna Allen, J. Derek Johnson and Ksenija Vujnovic 2006 Front page: Open Labradour tea / lichen community with scattered black spruce. Photo by L. Allen ISBN No. 0-7785-4694-2 For copies of this report, contact: Alberta Natural Heritage Information Centre Alberta Community Development 2nd Floor, 9820 – 106 Street Edmonton, AB T5K 2J6 780-427-6621 This publication may be cited as: Allen, L., J. D. Johnson and K. Vujnovic. 2006. Small Patch Communities of Caribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park. A report prepared for Parks and Protected Areas, Alberta Community Development, Edmonton, Alberta. 43 pp. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 The Study Area……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Methods……………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Results ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ecological Communities Documented …………………………………………………………… 7 Detailed Ecological Community Information …………………………………………………… 8 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 References Cited …………………………………………………………………………………… 19 Appendices Appendix 1. Unusual communities or habitats that potentially occur in the Caribou Mountains from literature review………………………………………………… 23 Appendix 2. Communities on the Preliminary Ecological Community Tracking List that occur in the Boreal Forest Natural Region ……………………………………