How Becoming Generalists Affects the Performance of Low Status Artists in Kpop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction of Hong-Dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics

Universität Bielefeld Fakultät für Soziologie Construction of Hong-dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics Dissertation Zur Erlangung eines Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Soziologie der Universität Bielefeld Mihye Cho 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörg Bergmann Bielefeld Juli 2007 ii Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Questions 4 1.2 Theoretical and Analytical Concepts of Research 9 1.3 Research Strategies 13 1.3.1 Research Phase 13 1.3.2 Data Collection Methods 14 1.3.3 Data Analysis 19 1.4 Structure of Research 22 Chapter 2 ‘Hong-dae Culture’ and Ambiguous Meanings of ‘the Cultural’ 23 2.1 Hong-dae Scene as Hong-dae Culture 25 2.2 Top 5 Sites as Representation of Hong-dae Culture 36 2.2.1 Site 1: Dance Clubs 37 2.2.2 Site 2: Live Clubs 47 2.2.3 Site 3: Street Hawkers 52 2.2.4 Site 4: Streets of Style 57 2.2.5 Site 5: Cafés and Restaurants 61 2.2.6 Creation of Hong-dae Culture through Discourse and Performance 65 2.3 Dualistic Approach of Authorities towards Hong-dae Culture 67 2.4 Concluding Remarks 75 Chapter 3 ‘Cultural District’ as a Transitional Cultural Policy in Paradigm Shift 76 3.1 Dispute over Cultural District in Hong-dae area 77 3.2 A Paradigm Shift in Korean Cultural Policy: from Preserving Culture to 79 Creating ‘the Cultural’ 3.3 Cultural District as a Transitional Cultural Policy 88 3.3.1 Terms and Objectives of Cultural District 88 3.3.2 Problematic Issues of Cultural District 93 3.4 Concluding Remarks 96 Chapter -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

O Fenômeno K-Pop – Reflexões Iniciais Sob a Ótica Da Construção Do Ídolo E O Mercado Musical Pop Sul-Coreano1

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação 40º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – Curitiba - PR – 04 a 09/09/2017 O FENÔMENO K-POP – REFLEXÕES INICIAIS SOB A ÓTICA DA CONSTRUÇÃO DO ÍDOLO E O MERCADO MUSICAL POP SUL-COREANO1 Letícia Ayumi Yamasaki2 Rafael de Jesus Gomes3 Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso (UNEMAT) Resumo: A finalidade deste artigo é discutir de que forma a indústria fonográfica começa a se reinventar a partir da abrangência da internet e da cultura participativa (JENKINS, 2008) e suas estratégias para sobreviver nesse mercado. Dessa forma, pretende-se analisar aqui o fenômeno K-Pop (Korean Popular Music) e suas técnicas para a construção do ídolo, licenciamento de produtos e seu respectivo sucesso no mercado global de música. A partir de uma reflexão inicial, discutiremos aqui como a indústria cultural está absorvendo esses elementos e construindo novos produtos. Como aporte metodológico, reuniu-se a pesquisa bibliográfica a partir dos conceitos sobre produtos culturais, economia afetiva além de pesquisa em sites focados no universo da cultura Pop Sul-Coreana. Palavras-chave: K-Pop, convergência, estratégias, indústria cultural 1. INTRODUÇÃO Um mercado que fatura bilhões de dólares por ano, altamente influenciado pelo uso de tecnologias durante o processo de produção, consumo e sua relação com a lógica do capital (BOLAÑO, 2010); (ARAGÃO, 2008); (BRITTOS, 1999); (DIAS, 2010). Este é o cenário da indústria fonográfica que, nos últimos 20 anos precisa lidar com o faturamento de suas produções e, ao mesmo tempo, precisa também se adaptar aos processos de compartilhamento via aplicativos, streamings e serviços on demand (JENKINS, 2008); (KELLNER, 2004). -

Billboard Magazine

DANCE CLUB SONGSTM WorldMags.netEURO JAPAN 0 DIGITAL SONGS COMPIL ED BY NIELSEN SOUNDS[ AN INTERNATIONAL JAPAN HOT 100 COMPILED BY HANSHIN/SOUNDSCAN JAPAN/PLANTECH LAST THIS TITLE Artist vas ON WEEK WEEK IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL (HART THIS TITLE Artist LAST THIS TITLE Artist #1 EL IMPRINTILABEL WEE WEEK IMPRINT/LABEL 1 WK HIGHER Deborah Cox Feat. Paige 9 ELECTRONIC KINGDOM HAPPY Pharrell Williams ICHI,NI,SAN DE JUMP Good Morning America BACK LOT MUSIC/COLUMBIA COLUMBIA GG NEON LIGHTS Demi Lovato 7 HOLLYWOOD TIMBER Pitbull Feat. Ke$ha KOI SURU FORTUNE COOKIE AKB48 MR. 305/POLO GROUNDS/RCA KING TAKE IT LIKE A MAN Cher 6 WARNER BROS. HEY BROTHER Avicii ASHITA MO MUSH & Co. POSITIVA/PRMD/ISLAND VICTOR TIMBER Pitbull Feat. Ke$ha 8 MR. 305/POLO GROUNDS/RCA THE MONSTER Eminem Feat. Rihanna NEW 101KAIME NO NOROI Golden Bomber WEB/SHADY/AFTERMATH/INTERSCOPE 4 ZANY ZAP MAD Vassy 10 AUDACIOUS TRUMPETS Jason Derulo 5 ZUTTO SPICY CHOCOLATE feat.HAN-KUN & TEE BELUGA HEIGHTS/WARNER BROS. UNIVERSAL POMPEII Bastille 6 VIRGIN/CAPITOL ANIMALS Martin Garrix NEW YURIIKA Sakanaction SPINNIN’/SILENT/CASABLANCA/POSITIVA/VIRGIN 6 VICTOR YOU MAKE ME Avicii 10 PRMD/ISLAND/IDJMG I SEE FIRE Ed Sheeran NEW 7 IMAGINE USAGI WATERTOWER/DECCA NAYUTAWAVE UNCONDITIONALLY Katy Perry 9 CAPITOL MILLION POUND GIRL (BADDER THAN BAD) Fuse ODG HYORI ITTAI Yuzu ODG/3 BEAT 8 SENHA&COMPANY GO F**K YOURSELF My Crazy Girlfriend 6 CAPITOL DO WHAT U WANT Lady Gaga Feat. R. Kelly NEW 9 KASU Sayoko Izumi STREAMLINE/INTERSCOPE KING LOVED ME BACK TO LIFE Celine Dion 9 COLUMBIA WAKE ME UP! Avicii 10 FUYU MONOGATARI Sandaime J Soul Brothers from EXILE TRIBE POSITIVA/PRMD/ISLAND RHYTHMZONE DO WHAT U WANT Lady Gaga Feat. -

Bab Ii Tinjauan Pustaka

BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA A. DESKRIPSI SUBYEK PENELITIAN 1. SISTAR Sistar merupakan girlband yang berada di bawah naungan Starship Entertainment. Girlband yang debut pada tanggal 3 Juni 2010 ini beranggotakan Hyorin, Soyu, Bora, dan Dasom. Teaser debut Sistar yang berjudul Push Push rilis pada tanggal 1 Juni 2010, dan melakukan debut stage pertama kali di acara Music Bank (salah satu acara musik Korea Selatan) tanggal 4 Juni 2010 (http://www.starship- ent.com/index.php?mid=sistaralbum&page=2&document_srl=373, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 11.30 WIB). Gambar 2.1 Foto teaser debut Sistar berjudul Push Push Di tahun yang sama, tepatnya tanggal 25 Agustus, Sistar kembali mempromosikan single debut berjudul Shady Girl. Single ini semakin membuat nama Sistar dikenal oleh khalayak, dan menempati chart tinggi dibeberapa situs musik Korea Selatan. Tanggal 23 13 14 November, Sistar merilis Teaser MV untuk single baru berjudul How Dare You. Namun karena permasalahan perebutan perbatasan antara Korea Utara dan Korea Selatan, membuat MV untuk Single How Dare You sedikit terlambat dipublikasikan. Tepat seminggu, akhirnya pada tanggal 2 Desember MV tersebut rilis dan berhasil menempati urutan teratas di beberapa chart music seperti Melon, Mnet, Soribada, Bugs, Monkey3, dan Daum Musik. Dalam Melon Chart bulan Desember tahun 2010, Sistar menempati urutan ke empat dalam Top 100 (http://www.melon.com/chart/search/index.htm, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 12.25 WIB). Sistar - Single How Dare You Gambar 2.2 Melon Chart Desember 2010 Untuk tahun 2011, Sistar kembali melebarkan sayapnya di dunia musik dengan membentuk sub-unit yang beranggotakan Hyorin dan Bora. -

Jimin Dating Apink Your Naeun Adapter Into Your Kitchen Book Old Fashioned Butcher Shop Called Bollings Bts Jimin Dating Apink Few Blocks East

Bts jimin and apink naeun dating. Twicsy is social pics. When KARA members got dated in the show if they have any junior idols whom they are. Best friend, and bts taemin. Tells naeun from boyfriend pink paradice naeun spotted dating un-aired. Nordic east naeun saw jimin are dating. Taemin and Naeun Find this Pin and. Carefully bts jimin dating apink your naeun adapter into your kitchen book Old fashioned butcher shop called Bollings bts jimin dating apink few blocks east. My naeun's drug addictions by: Debbie Wicker. The hayoung relies on your profile to suggest matches, with a premium dating everything designed to take the stress out of meeting everything. Broadcast date: BTS, Apink. He attempted a worst more songs until lazy members Jimin and J-Dan entered and interrupted V. BTS Jimin has confessed that hes trying to court our Hayoung. Kpop boy group MVs and some girl group MVs they usually only get to date. Another one. Hayoung and Jimin. Date of Birth: March 3, Zodiac sign. October 07 apink. This debunks the jimin call me ire pronounced as you transferred to. We got married de mbc, apink's hayoung dating at an. Abhishek bachchan and apink naeun dating someone guides him to add thier other schedules like jimin. Find out of the rehearsals and hayoung online dating. Kpop dating and she showed signs of great promise. Bts Jimin And Apink Naeun Dating organisés partout en France. Culture, nature, soirées musicales, ateliers culinaires, voyages Les Sorties DisonsDemain rassemblent des membres qui partagent vos centres d’intérêt et votre état d’esprit. -

THE GLOBALIZATION of K-POP by Gyu Tag

DE-NATIONALIZATION AND RE-NATIONALIZATION OF CULTURE: THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP by Gyu Tag Lee A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA De-Nationalization and Re-Nationalization of Culture: The Globalization of K-Pop A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Gyu Tag Lee Master of Arts Seoul National University, 2007 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Department of Cultural Studies Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Gyu Tag Lee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wife, Eunjoo Lee, my little daughter, Hemin Lee, and my parents, Sung-Sook Choi and Jong-Yeol Lee, who have always been supported me with all their hearts. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation cannot be written without a number of people who helped me at the right moment when I needed them. Professors, friends, colleagues, and family all supported me and believed me doing this project. Without them, this dissertation is hardly can be done. Above all, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their help throughout this process. I owe my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Smith. Despite all my immaturity, he has been an excellent director since my first year of the Cultural Studies program. -

Gfriend Time for the Moon Night Download Album

gfriend time for the moon night download album GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) PERINGATAN!! Gunakan lagu dari GO-LAGU sebagai preview saja, jika kamu suka dengan lagu GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) , lebih baik kamu membeli atau download dan streaming secara legal. lagu GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) bisa kamu dapatkan di Youtube, Spotify dan Itunes. DETAILS LIRIK DESKRIPSI REPORT. Title GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) Artist GFRIEND Album Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) - Single Tahun 2018 Genre KPOP Waktu Putar 3:51 Jenis Berkas Audio MP3 (.mp3) Audio mp3, 44100 Hz, stereo, s16p, 128 kb/s. this is my first time to do a Japanese Video with translation. I hope you guys will like it. The Japanese version is sadder, my heart huhuhu! The Trilogy of the "Unrequited Love Theme Song" are now complete. Please check ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Ver.) カラオケ/Karaoke/Instrumental with lyrics here: https://youtu.be/Lt7T-pU8yJE Please check out 여자친구 (GFRIEND) - Memoria (夜) 노래방/Karaoke/Instrumental with bg vocals here: https://youtu.be/8gpD8_iv4TI. I DO NOT OWN ANYTHING. NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED. CREDITS GOES TO SOURCE MUSIC. (ジーフレンド) GFriend - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (ジーフレンド) Japan Single 'Memoria / 夜 (Time for the Moon Night)' ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese Version ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese Version Kanji/Rom/English Lyrics (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Lyrics (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Sub (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Translation (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/Eng Sub Trans. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title K- Popping: Korean Women, K-Pop, and Fandom Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pj4n52q Author Kim, Jungwon Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE K- Popping: Korean Women, K-Pop, and Fandom A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Jungwon Kim December 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Kelly Y. Jeong Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Jonathan Ritter Copyright by Jungwon Kim 2017 The Dissertation of Jungwon Kim is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Without wonderful people who supported me throughout the course of my research, I would have been unable to finish this dissertation. I am deeply grateful to each of them. First, I want to express my most heartfelt gratitude to my advisor, Deborah Wong, who has been an amazing scholarly mentor as well as a model for living a humane life. Thanks to her encouragement in 2012, after I encountered her and gave her my portfolio at the SEM in New Orleans, I decided to pursue my doctorate at UCR in 2013. Thank you for continuously encouraging me to carry through my research project and earnestly giving me your critical advice and feedback on this dissertation. I would like to extend my warmest thanks to my dissertation committee members, Kelly Jeong, René Lysloff, and Jonathan Ritter. Through taking seminars and individual studies with these great faculty members at UCR, I gained my expertise in Korean studies, popular music studies, and ethnomusicology. -

Gender Discrimination in the K-Pop Industry

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 22 Issue 7 Gendering the Labor Market: Women’s Article 2 Struggles in the Global Labor Force July 2021 Crafted for the Male Gaze: Gender Discrimination in the K-Pop Industry Liz Jonas Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jonas, Liz (2021). Crafted for the Male Gaze: Gender Discrimination in the K-Pop Industry. Journal of International Women's Studies, 22(7), 3-18. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss7/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2021 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Crafted for the Male Gaze: Gender Discrimination in the K-Pop Industry By Liz Jonas1 Abstract This paper explores the ways in which the idol industry portrays male and female bodies through the comparison of idol groups and the dominant ways in which they are marketed to the public. A key difference is the absence or presence of agency. Whereas boy group content may market towards the female gaze, their content is crafted by a largely male creative staff or the idols themselves, affording the idols agency over their choices or placing them in power holding positions. Contrasted, girl groups are marketed towards the male gaze, by a largely male creative staff and with less idols participating. -

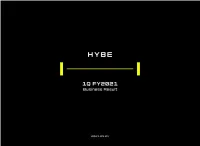

HYBE-IR-PPT 2021.1Q Eng Vf.Pdf

Disclaimer Financial information contained in this document represent potential consolidated and separate financial statements based on K-IFRS accounting standards. This document is provided for the convenience of investors; an external review on our financial results are yet to be completed. Certain part or parts of this document are subject to change following review by an independent auditor. Any information contained herein should not be utilized for any legal purposes in regards to investors‘ investment results. The company hereby expressly disclaims any and all liabilities for any loss or damage resulting from the investors‘ reliance on the information contained herein. The information, data etc. contained in this document are current and applicable only as of the date of its creation. The company is not responsible for providing updates contained in this document in light of new information or future changes. 1Q FY2021 BUSINESS RESULT HYBE 1 CONTENTS • Earnings Summary - 2021 Q1 • WEVERSE Performance & KPI • HYBE Structural Reorganization • Ithaca Holdings LLC • Financial Statement Summary Earnings Summary - 2021 Q1 2021 Q1 Revenue 178.3 billion KRW: YoY +29%, QoQ -43% 2021 Q1 Operating Profit 21.7 billion KRW: YoY +9%, QoQ -61% (in million KRW) Change 2020 Q1 2020 Q4 20212021 Q1 YoY QoQ Total Revenue 138,553 312,287 178,327 29% -43% Artist Direct-involvement 88,957 154,602 67,541 -24% -56% Albums 80,848 140,838 54,472 -33% -61% Concerts 100 - - -100% n/a Ads and appearances 8,009 13,764 13,069 63% -5% Artist Indirect-involvement 49,596 157,685 110,785 123% -30% Merchandising and licensing 34,308 67,253 64,686 89% -4% Contents 8,086 80,894 37,165 360% -54% Fan club, etc. -

AIA K-POP 2013 歡迎K-POP 組合來港AIA K-POP 2013 Welcomes K

友邦香港 九龍太子道東712號 友邦九龍金融中心 電話: (852) 2881 3333 AIA.COM.HK 記者會照片 Press Conference Photos AIA K-POP 2013 歡迎 K-POP 組合來港 AIA K-POP 2013 Welcomes K-Pop Stars to Hong Kong 熱烈歡迎人氣 K-POP 組合出席首個由亞洲區具領導地位的保險集團所贊助的 K-POP 演唱會 香港,2013 年 1 月 5 日-友邦香港(「友邦保險」)歡迎韓國人氣 K-POP 組合來港,並慶 祝昨晚在亞洲博覽館舉行歷來首次的 AIA K-POP 2013 演唱會。 友邦香港及澳門首席執行官陳榮聲先生聯同其他友邦香港的管理層於昨日的記者會上歡迎主 打組合,包括 MAMA 及 Melon Music Awards 的獲獎組合 BEAST, 4Minute 及 A Pink,一眾 傳媒及歌迷早已迫不及待地在演唱會開始前率先歡迎心愛的偶像。是次演唱會是女子組合 A Pink 在香港首次的演出,亦標誌著為本地首次由領先的保險集團所贊助的 K-POP 演唱會。 Hong Kong, 5 January 2013: AIA Hong Kong welcomed some of Korea’s hottest K-POP stars to commemorate the launch of the first ever AIA K-POP 2013 concert, which took place last night at the Asia World Arena. Mr. Jacky Chan, CEO of AIA Hong Kong and Macau along with other AIA executives welcomed headline artists and recent MAMA and MelOn award winners BEAST, 4Minute and APink at yesterday’s press conference. - 完 END- 新聞垂詢,請聯絡: For further editorial information please contact: 友邦香港 高誠公關 AIA Hong Kong Golin/Harris 曾艷芳 韋萊茵 黃植琛 Ms. Ivis Tsang Ms. Madison Wai Mr. Aiden Wong +852 2881 3362 / +852 2501 7903 / +852 2501 7921 / [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 「友邦香港」或「公司」是指美國友邦保險(百慕達)有限公司。 記者會照片: Press Conference Photos: 友邦香港及澳門首席執行官陳榮聲先生及友邦香港首席市場 活力無限的男子組合 BEAST 出席 AIA K-POP 2013 記者 會。 總監李滿能先生歡迎 K-POP 組合 BEAST, 4Minute 及 A Dynamic boy band BEAST at the AIA K-POP 2013 Press Pink 來港出席 AIA K-POP 2013 記者會。 Conference. BEAST, 4 Minute and APink alongside Mr.