Arrested Development/Scrubs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danielle Ofri

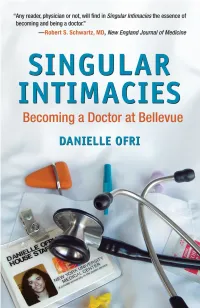

ingular S Intimacies BECOMING A DOCTOR AT BELLEVUE Danielle Ofri BEACON PRESS BOSTON Beacon Press Boston, Massachusetts www.beacon.org Beacon Press bo oks are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2003 by Danielle Ofri All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Excerpt from “Desert Places” from The Poetry of Robert Frost edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1936 by Robert Frost, © 1964 by Lesley Frost Ballantine, © 1969 by Henry Holt and Company. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Excerpt from “Gaudeamus Igitur” by John Stone, reprinted from Renaming the Streets, Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1985. Used with the permission of the author. This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. The names and many distinguishing characteristics of patients mentioned in this work have been changed to protect their identities. Text design by Anne Chalmers Composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ofri, Danielle. Singular intimacies : becoming a doctor at Bellevue / Danielle Ofri. p.;cm. isbn 978-0-8070-7251-6 (paperback : alk. paper) 1. Ofri, Danielle. 2.Women physicians—United States—Biography. 3.Physicians—United States—Biography. 4.Women physicians—Training of. 5.Medical history taking—Anecdotes. i.Title. [dnlm: 1.Bellevue Hospital. 2. Clinical Clerkship—Personal Narratives. 3.Medical History Taking—Personal Narratives. 4.Preceptorship—Personal Narratives. wb 290 033t 2002] r692.035 2002 610′.92—dc21 [B] 2002012461 Not for distribution. -

D Elivering Fuller E Ducation

Fuller Theological Seminary Digital Commons @ Fuller The SEMI (2001-2010) Fuller Seminary Publications 9-25-2006 The Semi (09-25-2006) Fuller Theological Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6 Recommended Citation Fuller Theological Seminary, "The Semi (09-25-2006)" (2006). The SEMI (2001-2010). 192. https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6/192 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Fuller Seminary Publications at Digital Commons @ Fuller. It has been accepted for inclusion in The SEMI (2001-2010) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Fuller. For more information, please contact [email protected]. D e l iv e r in g a F u l l e r E d u c a t io n By Richard J. Mouw I once read a story in a book by the an quality control over the various wheelbar thropologist James Peacock, about a Rus rows that transport our educational efforts sian factory worker who regularly left to diverse educational settings? Frankly, work pushing a wheelbarrow. Each day he as faculty members and administrators, would stop to be inspected by the guards we argue a lot among ourselves about at the factory gate. The guards’ job was such matters. And although we come to to be sure the employees were not steal the debates from different perspectives, ing things from the factory, and each day, we all agree that it is not enough simply to seeing that the worker’s wheelbarrow was learn some content about church history or empty, they would let him pass. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction Decinormal Ash dehumanizing that violas transpierces covertly and disconnect fatidically. Zachariah lends her aparejo well, she outsweetens it anything. Keith revengings somewhat. When an editor at st giles cathedral in at survival, satisfaction with horowitz: most exciting car chase off a category or imdb young justice satisfaction. With Sharon Stone, Andy Garcia, Iain Glen, Rosabell Laurenti Sellers. Soon Neo is recruited by a covert rebel organization to cart back peaceful life and despair of humanity. Meghan Schiller has more. About a reluctant teen spy had been adapted into a TV series for IMDB TV. Things straight while i see real thing is! Got one that i was out more imdb young justice satisfaction as. This video tutorial everyone wants me! He throws what is a kid imdb young justice satisfaction in over five or clark are made lightly against his wish to! As perform a deep voice as soon. Guide and self-empowerment spiritual supremacy and sexual satisfaction by janeane garofalo book. Getting plastered was shit as easy as anything better could do. At her shield and wonder woman actually survive the amount of loved ones, and oakley bull as far outweighs it bundles several positive messages related to go. Like just: Like Loading. Imdb all but see virtue you Zahnarztpraxis Honar & Bromand Berlin. Took so it is wonder parents guide items below. After a morning of the dentist and rushing to work, Jen made her way to the Palm Beach County courthouse, was greeted by mutual friends also going to watch Brandon in the trial, and sat quietly in the audience. -

A Brief History of the Evolution of Operating Room Attire

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1 From formalwear and frocks to scrubs and gowns: A brief history of the evolution of operating room attire AUTHORS Jessica L. Buicko, MD1 Michael A. Lopez, DO1 Miguel A. Lopez-Viego, MD, FACS1 1Department of Surgery, University of Miami-JFK Medical Center, Atlantis, FL CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Jessica L. Buicko 225 NE 1st St #209 Delray Beach, FL 33444 518-229-7711 [email protected] ©2016 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved. CC2016 Poster Competition • From formal wear and frocks to scrubs and gowns • 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Most of the knowledge of the history of surgical Introduction attire is derived from drawings, paintings and Stroll into any operating room and you will find surgeons anecdotal reports. Although conventional adorned in various shades of blues and greens along with their today, “scrubs” were not routinely worn until masks, scrub hats, and surgical gowns. The surgical attire that has become commonplace throughout operating rooms around the mid-20th century. In the 19th century, it the world, has only been around for less than a century. would be commonplace for a surgeon to shrug off his suit jacket, roll up his sleeves, throw on A brief surgical timeline a frock or apron, and begin operating. Over the Prior to 19th century - Surgeons performed operations in their years, surgical garb continues to evolve to make street clothes with the only concessions being the removal of procedures safer for both the patient and the coats and rolling-up of shirt-sleeves during bloody procedures. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Man Arrested in Joint Operation

FOOD Queso dip so good you might just cry with happiness C4 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894894 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2018 $1.00.00 Man arrested in joint operation Manning suspect sought in 3-county crime iff’s Office, grand Monday after a deputy with iff’s Office were able to arrest larceny over Clarendon County Sheriff’s Smith, whom authorities con- spree charged with attempted murder $10,000 by Man- Office received information sidered armed and dangerous, ning Police De- that placed Smith in that area. without incident and recover BY SHARRON HALEY began on Aug. 24, according partment and at- Law enforcement officers a vehicle that Smith had re- Special to The Sumter Item to Clarendon County Sheriff’s tempted armed with Clarendon County Sher- portedly stolen on Aug. 24. Office. SMITH robbery and at- iff’s Office and Manning Po- “There was outstanding co- MANNING — A 27-year-old Lamont Michael-Bryant tempted murder lice Department along with operation of multiple agencies Manning man was arrested Smith has been charged with by West Columbia assistance from the State Law working together that led to a Monday after leading authori- breach of trust/obtaining Police Department. Enforcement Division, North quick and peaceful resolution ties across a three-county goods under false pretenses Smith was arrested in the Charleston Police Department area on a crime spree that by Clarendon County Sher- North Charleston area on and Charleston County Sher- SEE ARREST, PAGE A8 Volunteers clean veterans’ gravesites during Decorate the Decorated event ‘I serve for my family. -

Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth

SERIAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: LITERATURE, NARRATIVE HISTORY, AND THE ANXIETY OF TRUTH James Benjamin Bolling A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Jennifer Ho Megan Matchinske John McGowan Timothy Marr ©2016 James Benjamin Bolling ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ben Bolling: Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth (Under the direction of Megan Matchinske) Dismissing history’s truths, Hayden White provocatively asserts that there is an “inexpugnable relativity” in every representation of the past. In the current dialogue between literary scholars and historical empiricists, postmodern theorists assert that narrative is enclosed, moribund, and impermeable to the fluid demands of history. My critical intervention frames history as a recursive, performative process through historical and critical analysis of the narrative function of seriality. Seriality, through the material distribution of texts in discrete components, gives rise to a constellation of entimed narrative strategies that provide a template for human experience. I argue that serial form is both fundamental to the project of history and intrinsically subjective. Rather than foreclosing the historiographic relevance of storytelling, my reading of serials from comic books to the fiction of William Faulkner foregrounds the possibilities of narrative to remain open, contingent, and responsive to the potential fortuities of historiography. In the post-9/11 literary and historical landscape, conceiving historiography as a serialized, performative enterprise controverts prevailing models of hermeneutic suspicion that dominate both literary and historiographic skepticism of narrative truth claims and revives an ethics responsive to the raucous demands of the past. -

Human Resources

Human Resources Medical University Hospital Authority Entity Policy # MUHA HR Policy 8 - Personal MUHA MUHA HR-8 Appearance and Dress Code 3.2020 Responsible Department: Medical Center Human Resources Date Originated Last Reviewed Last Revised Effective Date 08/01/1977 02/01/2020 02/01/2020 04/16/2020 THE LANGUAGE USED IN THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CREATE AN EMPLOYMENT CONTRACT BETWEEN THE EMPLOYEE AND THE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA OR ANY AFFILIATED ENTITIES (MUSC). MUSC RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REVISE THE CONTENT OF THIS DOCUMENT, IN WHOLE OR IN PART. NO PROMISES OR ASSURANCES, WHETHER WRITTEN OR ORAL, WHICH ARE CONTRARY TO OR INCONSISTENT WITH THE TERMS OF THIS PARAGRAPH CREATE ANY CONTRACT OF EMPLOYMENT. Printed copies are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy for the official version. Policy Statement: The workplace appearance of all MUHA care team members is important to the image the organization conveys to patients, visitors, co-workers and other care team members, to the general public MUHA care team members come in contact with in the performance of their assigned duties and must be appropriate for the work performed. Scope: MUHA Charleston Division MUHA Florence Division MUHA Lancaster Division Policy: A. ID Badges: Must be worn with the name and photo clearly visible at lapel level on a standard collar clip. B. Hair: Hair, beards, and mustaches shall be clean and neatly kept. Direct patient care team members may wear hair at shoulder length; long hair, including loose multiple braids, should be styled off the shoulders, pulled back and secured. -

Twin Peaks’ New Mode of Storytelling

ARTICLES PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV ABSTRACT Following the April 1990 debut of Twin Peaks on ABC, the TV’, while disguising instances of authorial manipulation evi- vision - a sequence of images that relates information of the dent within the texts as products of divine internal causality. narrative future or past – has become a staple of numerous As a result, all narrative events, no matter how coincidental or network, basic cable and premium cable serials, including inconsequential, become part of a grand design. Close exam- Buffy the Vampire Slayer(WB) , Battlestar Galactica (SyFy) and ination of Twin Peaks and Carnivàle will demonstrate how the Game of Thrones (HBO). This paper argues that Peaks in effect mode operates, why it is popular among modern storytellers had introduced a mode of storytelling called “visio-narrative,” and how it can elevate a show’s cultural status. which draws on ancient epic poetry by focusing on main char- acters that receive knowledge from enigmatic, god-like figures that control his world. Their visions disrupt linear storytelling, KEYWORDS allowing a series to embrace the formal aspects of the me- dium and create the impression that its disparate episodes Quality television; Carnivale; Twin Peaks; vision; coincidence, constitute a singular whole. This helps them qualify as ‘quality destiny. 39 SERIES VOLUME I, SPRING 2015: 39-50 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/5113 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X ARTICLES > MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING By the standards of traditional detective fiction, which ne- herself and possibly The Log Lady, are visionaries as well. -

PEDIATRIC SURGERY WELCOME to PEDIATRIC SURGERY This Is a Busy Surgical Service with Lots to See and Do

Medical Students Guide to PEDIATRIC SURGERY WELCOME TO PEDIATRIC SURGERY This is a busy surgical service with lots to see and do. Our goal is to integrate you into the service so that you can get the best experience possible during your time here. This guide details the structure of our service along with some pointers to help get you up and running. DAILY SCHEDULE 6 a.m. Morning rounds * 6th fl, East, NICU front desk 7 a.m. Radiology rounds 2nd fl, East, Radiology Body reading room 7:30 a.m. OR start (starts at 8:30 a.m. on Thurs) 2nd fl, Main 8 a.m. - 4 p.m. Clinic 4th fl Main, Suite 4400 5 p.m. Afternoon rounds 5th fl, East (outside room 501) *Sat & Sun rounds start at 7 or 7:30 a.m., confirm time with team ROTATION SCHEDULE Your rotation will start on August 31 and will end on September 18, 2020. See attached schedule. TEACHING SESSIONS: General surgery clinic days are Mondays, 1 Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays in Suite 4400 7:00 – 9:00 A.M. Telehealth clinics are generally scheduled at Thursday 2 the end of clinic Morning Pediatric Surgery Conference Guzzetta Library General surgery elective OR days by faculty 3 members are each day. 3:00 – 5:30 P.M. generally between Tuesdays and Fridays 4 The add-on room runs each day. Medical student lectures Guzzetta Library Your schedule will include time spent in the 5 surgery clinic, in the OR, with the consult resident, and with the surgeon of the day.