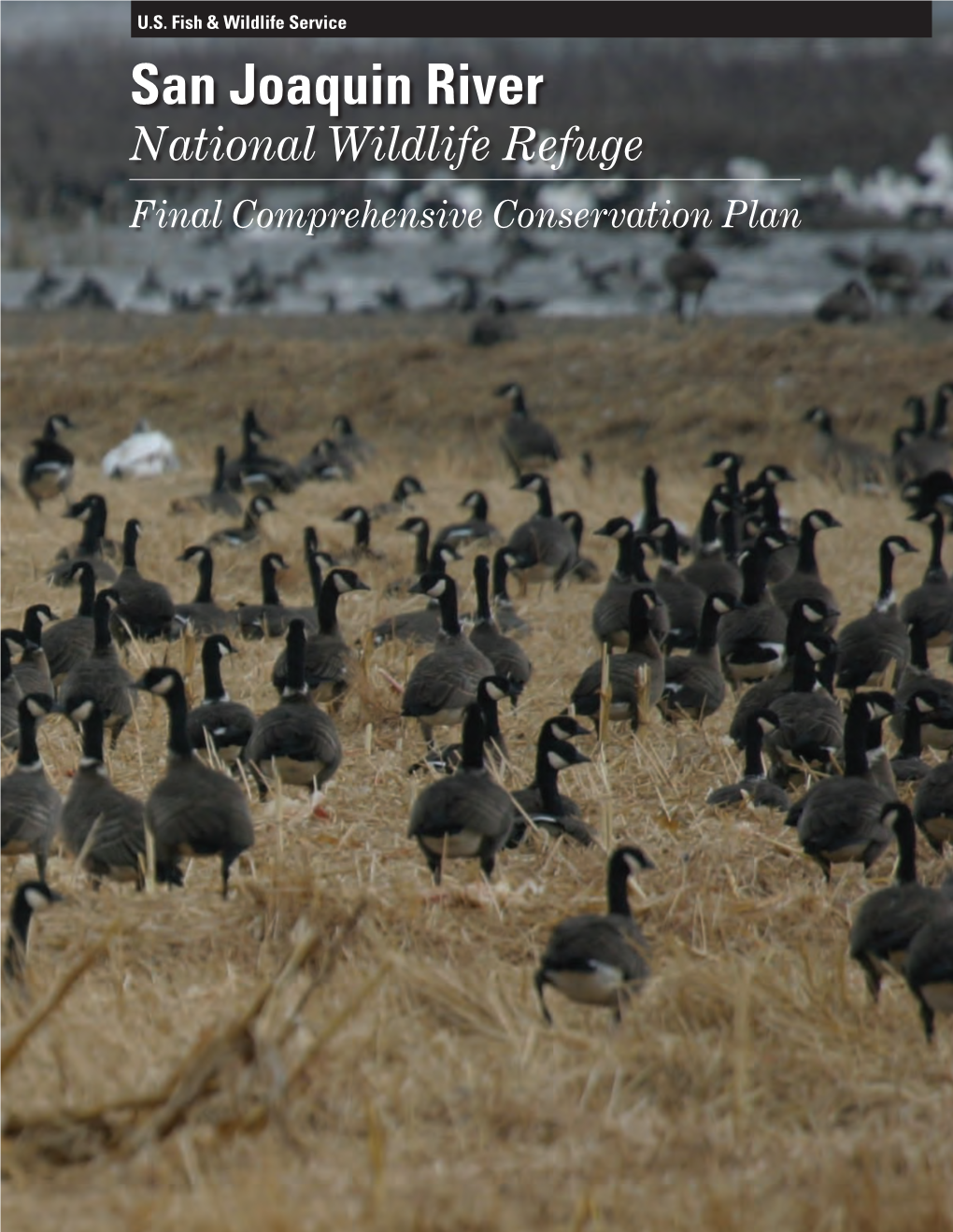

San Joaquin River NWR Comprehensive Conservation Plan I Mosquito Abatement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing Indicators of Stream Health in the Tuolumne Watershed

Assessing Indicators of Stream Health in the Tuolumne Watershed By: Devon Lambert, Robert Miyashiro, Miles Ryan, and Sarah Baird Ecogeomorphology, Spring 2014 University of California, Davis Abstract The Tuolumne River watershed, ranging from Yosemite National Park in the high Sierra Nevada mountains to the central valley floor, contains multiple dams that provide a range of services from water supply and hydroelectric generation to recreation. We studied the impacts of these dams on the Tuolumne river ecology by assessing a series of stream health indicators in regulated and unregulated portions of the watershed. Data was collected on channel bed substrate distributions, algal biomass, benthic macroinvertebrates, and fish assemblages as indicators of overall stream health. Our findings indicate that dams, and especially daily pulse flows released below the dams, alter the variables for which we collected data. We provide some information on the costs and benefits to environmental flows in the Tuolumne River and suggest management of water releases below dams can be shaped to sustain essential ecosystem functions, without severely altering the economic and water delivery benefits. Implementing changes to the flow regime that will benefit the ecosystem, such as better mimicking the characteristics of the spring snowmelt recession or limiting pulse flows to the appropriate high flow season, is attainable and affordable within the Tuolumne watershed. Introduction The Tuolumne river watershed lies in the southern portion of the Western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and encompasses 1,958 square miles. There are four dams within the watershed primarily used for hydroelectric power, recreational flows, and a steady water supply during California’s dry summers. -

HYDROLOGY and WATER QUALITY 3.8 Hydrology and Water Quality

3.8 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY 3.8 Hydrology and Water Quality This section of the Draft EIR addresses the potential for the Merced General Plan to affect or modify the existing hydrology and water quality of the Planning Area. Two comment letters were received on the NOP from the Merced Irrigation District (MID) in which they said that they would “Upon development of new and existing land covered within the scope of the 2030 General Plan, MID will provide a detailed response in regards to the proposed projects and their impacts upon MID facilities.” The second letter received was in response to the NOP regarding hydrology and water quality. The commenter wants the City to prepare a Water Element and “perform an environmental review of the potentially positive environmental effects that could be based upon such additional elements.” 3.8.1 SETTING Environmental Setting CLIMATE The climate of the City of Merced is hot and dry in the summer and cool and humid in the winter. The average daily temperature ranges from 47 to 76 degrees Fahrenheit. Extreme low and high temperatures of 15°F and 111°F are also known to occur. Historical average precipitation is approximately 12” per year, with the rainy season commencing in October and running through April. On average, approximately 80% of the annual precipitation occurs between November and March. The hot and dry weather of the summer months usually results in high water demands for landscape irrigation during those months. REGIONAL TOPOGRAPHY The project area is located in and immediately adjacent to the City of Merced. -

State and Private Forestry, Tribal Relations Regions 1 & 4 Tribes Of

State and Private Forestry, Tribal Relations Regions 1 & 4 Tribes of Interest by State State Tribe(s) Idaho Coeur D’ Alene Tribe Idaho Nez Perce Tribe Idaho Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Idaho Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Montana Blackfeet Nation Montana Chippewa Tribe Montana/Wyoming Crow Nation Montana Fort Belknap Indian Community Montana Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes Montana Northern Cheyenne Tribe Montana Rocky Boys Chippewa Cree Montana Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes Montana Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians Nevada Battle Mountain Band (Shoshone) Nevada/California Benton Paiute Nevada/California Bishop Colony (Paiute-Shoshone) Nevada/California Bridgeport Indian Colony (Paiute) Nevada Carson Colony (Washoe) Nevada Dresslerville Community (Washoe) Nevada Duckwater Shoshone Tribe Nevada Elko Band (Western Shoshone) Nevada Ely Shoshone Nevada Fallon Colony (Paiute and Shoshone) Nevada Fort McDermitt Nevada Las Vegas Paiute Nevada Lovelock Paiute Nevada Moapa Band of Paiute Nevada Pyramid Lake Paiute Nevada Reno-Sparks Colony (Washoe, Paiute, Shoshone) 1 State Tribe(s) Nevada Shoshone-Paiute Tribes Nevada South Fork Band Council Nevada Stewart Community Council Nevada Summit Lake Paiute Tribe Nevada Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Nevada/California Timbi-sha Shoshone Band Nevada Walker River Paiute Tribe Nevada/California Washoe Tribe: Includes: Carson, Dresslerville, Stewart, Washoe, Reno-Sparks, Woodsfords Colonies Nevada Wells Band Colony Nevada Winnemucca Colony Council (Paiute and Shoshone) Nevada/California Woodsfords -

Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River Project Information

Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River Project Information 1. Proposal Title: Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River 2. Proposal applicants: Steve Felte, Tri-Dam Project 3. Corresponding Contact Person: Jason Reed Tri-Dam Project P.O. Box 1158 Pinecrest, CA 95364 209 965-3996 [email protected] 4. Project Keywords: Anadromous salmonids At-risk species, fish Fish mortality/fish predation 5. Type of project: Research 6. Does the project involve land acquisition, either in fee or through a conservation easement? No 7. Topic Area: At-Risk Species Assessments 8. Type of applicant: Local Agency 9. Location - GIS coordinates: Latitude: 37.739 Longitude: -121.076 Datum: Describe project location using information such as water bodies, river miles, road intersections, landmarks, and size in acres. The proposed project will be conducted in the Stanislaus River between Knight’s Ferry at river mile 54.6 and the confluence with the San Joaquin River, in the mainstem San Joaquin River immediately downstream of the confluence, and in the deepwater ship channel near Stockton. 10. Location - Ecozone: 12.1 Vernalis to Merced River, 13.1 Stanislaus River, 1.2 East Delta, 11.2 Mokelumne River, 11.3 Calaveras River 11. Location - County: San Joaquin, Stanislaus 12. Location - City: Does your project fall within a city jurisdiction? No 13. Location - Tribal Lands: Does your project fall on or adjacent to tribal lands? No 14. Location - Congressional District: 18 15. Location: California State Senate District Number: 5, 12 California Assembly District Number: 25, 17 16. How many years of funding are you requesting? 3 17. -

Nye County Agenda Information Form

NYE COUNTY AGENDA INFORMATION FORM X Action a Presentation CI) Presentation & Action Agenda Number Department: Nye County Clerk I/ Category: Contact: Sandra Merlino Phone: 482-8127 Continued from meeting of: Action requested: (Include what, with whom, when, where, why, how much ($) and terms) Approval of the LLB Minutes for July 6,2004 and July 20, 2004 Complete description of requested action: (Include, if applicable, background, impact, long-term commitment, existing county policy, future goals, obtained by competitive bid, accountability measures) Approval of the LLB Minutes for July 6,2004 and July 20, 2004 Any information provided after the agenda is published or during the meeting of the Commissioners will require you to provide 10 copies: one for each Commissioner, one for the Clerk, one for the District Attorney, one for the Public and two for the County Manager. Contracts or documents requiring signature must be submitted with three original copies. Ex~enditureImpact by FY(s): (Provide detail on Financial Form) C;) No financial impact Routing & Approval (Sign ((l Date) I 1 Dept Date 1 6. Date I I I Date 2. 1 7. HR Date I I I 3. Date 1 8. Legal Date I I I Date 4. 1 9. Budgets Date 0 Approved 0 Disapproved 0 Amended as follows: 1 Clerk of the Board Date AGENDA FINANCIAL FORM Agenda Item No.: 1. Department Name: 2. Financial Contact Person: Direct Phone 3. Personnel Contact Person Direct Phone 4. Was the Budget Director consulted during the completion of this form (Y or N )? 5. Does this item require a budget adjustment to be made (Y or N)? 6. -

When Black Plus White Equals Gray: the Nature of Variation in the Variable Seedeater Complex (Emberizinae: Sporophila)

Volume 7 1996 No.2 ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 7: 75-107, 1996 CiJ'The Neotropical Ornithological Society WHEN BLACK PLUS WHITE EQUALS GRAY: THE NATURE OF VARIATION IN THE VARIABLE SEEDEATER COMPLEX (EMBERIZINAE: SPOROPHILA) F. Gary Stiles Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Apartado 7495, Bogotá D.C., Colombia. Resumen. Las afinidades taxon6micas del Espiguero Variable (Sporophila aurita) yel Espiguero Alifajeado (S. ameri- cana) han sido discutidos por más de 80 años. El descubrimiento de una zona de hibridizaci6n entre el primero y el Espiguero Gris (S. intermedia) -anteriormente no considerado como emparentado debido a que el plumaje definitivo del 0" es gris, no blanco y negro -me estimul6 a reexaminar esta cuesti6n. Mi hip6tesis de trabajo era que existiera una relaci6n estrecha entre todas estas formas. Esta hip6tesis fue apoyada por la gran similitud morfol6gica y las distribuciones casi perfectamente complementarias de todas ellas, la identificaci6n de otra zona de solapamiento y hibridizaci6n limitada, y por la existencia de variaci6n previamente ignorada dentro de la especie intermedia. Concluyo que S. intermedia es un miembro integral del llamado "complejo del Espiguero Variable", y que ésto constituye un grupo monofilético reconocible al nivel de superespecie.Los patrones de distri- buci6n geográfica y divergencia morfol6gica me permiten reconocer los siguientes cuatro aloespecies: S. corvina (Espiguero Variable); S. intermedia (Espiguero Gris); S. murallae (Espiguero del Caquetá); y S. americana (Espigue- ro Alifajeado). Con base en un análises cuantitativo de la variaci6n dentro de S. intermedia, llego a la conclusi6n de que la subespecie agustini no es reconocibre, como tampoco lo es S. -

I Sensitivity Analysis of California Water Supply

Sensitivity analysis of California water supply: Assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptations By Max Fefer B.S. (University of California, Berkeley) 2016 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Civil and Environmental Engineering in the OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS Approved: Jonathan Herman, Chair Jay Lund Samuel Sandoval-Solis Committee in Charge 2017 i Abstract Long-term changes in climate and population will have significant impacts on California’s freshwater management. Hydro-economic models can address climate change concerns by identifying system vulnerabilities and exploring adaptation strategies for statewide water operations. This thesis combines the new Python implementation of the CALVIN model, a hydro-economic model describing California water resources, with an ensemble of climate scenarios to identify adaptation strategies for managing water in a range of possible climates. A sensitivity analysis is performed by altering the magnitude and the timing of statewide inflows, defined as water availability and winter index respectively, to emulate changes in precipitation and temperature predicted by climate models. Model results show quadratic increases in shortage cost and marginal value of environmental flows, conveyance expansion, and reservoir expansion as water availability decreases. Reservoirs adapt to warmer climates by increasing average storage levels in winter and routing excess runoff to reservoirs downstream with available capacity. Both small and large changes to reservoir operations were observed compared to historical hydrology, showing that no single operating strategy achieves optimality for all reservoirs. Increasing the fraction of winter flow incurs small increases in total shortage cost, showing the state’s ability to manage a changing hydrologic regime with adaptive reservoir operations. -

Chlorospingus Flavovirens Rediscovered, with Notes on Other Pacific Colombian and Cauca Valley Birds

CHLOROSPINGUS FLAVOVIRENS REDISCOVERED, WITH NOTES ON OTHER PACIFIC COLOMBIAN AND CAUCA VALLEY BIRDS STEVEN L. HILTY ABSTRACT.--Aspecimen of the Yellow-green Bush Tanager collectedin 1972 was the first Colombianand third known specimensince the previoustwo taken in Ecuadorin 1935,and the specieshas not been reported since. Presentsnotes and new recordsof 36 other speciesfrom this region of high endemismon the westernslopes of the westernAndes.--Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson,Arizona 85721. Accepted2 June 1975. THE Pacific slope of Colombia records the highest annual rainfall in the Western Hemisphere (Rumney 1968), yet the distribution of many birds in this unique region of high endemism is still known chiefly through early collections(e.g. Cassin 1860; Bangs 1908, 1910; Chapman 1917) and the extensive collectionsof Von Sheidern (fide Meyer de Schauensee)during 1938, 1940, 1941, 1945, and 1946. This and other information has been compiledby Meyer de Schauensee(1948-52, 1964, 1966, 1970). Recent papers by Haffer (1967a, 1967b), Miller (1966), Olivares (1957a, 1957b, 1958), and Ralph and Chaplin (1973) contributeto our knowledgeof Pacific Colom- bian avifauna but the status of many speciesis still poorly known. The data reported here were obtained during portions of 1972, 1973 and 1975, chiefly in the AnchicayJ Valley at low to moderate elevationson the west slopeof the westernAndes and in the upper Cauca Valley near Cali, Department of Valle. Llano Bajo, Aguaclara, Saboletas,Danubio, and La Cascada, mentioned in text, are small villagesalong the Old BuenaventuraRoad, southof Buenaventura. Yatacu• is a site administered by the Corporaci6n Aut6noma del Valle del Cauca (C.V.C.) in the upper Anchicay/t Valley above the confluenceof the Rio Digua and Rio An- chicay/t. -

MAA FY 2021 Annual Work Plan | Iii Table of Contents

Management Agency Agreement Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Work Plan October 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021 Program to Meet Standards, California California-Great Basin Region U.S. Department of the Interior June 2020 Mission Statements The Department of the Interior (DOI) conserves and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, provides scientific and other information about natural resources and natural hazards to address societal challenges and create opportunities for the American people, and honors the Nation’s trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities to help them prosper. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Table of Contents Table of Contents Page Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Reclamation Staff Resources ........................................................................................................................ 11 Fiscal Year 2021 Goals and Objectives ...................................................................................................... 13 Detailed Description of FY 2021 Goals for the RTMP .................................................................... 13 Goal 1. Provide -

PIT Tag Monitoring for Emigrating Juvenile Chinook Salmon at Three Flow Conditions

PIT Tag Monitoring for Emigrating Juvenile Chinook Salmon at Three Flow Conditions Introduction Historically, California’s upper San Joaquin River (SJR) supported stable populations of fall- and spring-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). However, both populations were extirpated from the system in the mid-twentieth century following the development of Friant Dam (Moyle 2002). In response to the San Joaquin River litigation Settlement, the San Joaquin River Restoration Program (SJRRP) has implemented an objective to restore a naturally reproducing and self-sustaining population of Chinook salmon, as well as other fishes, in the system. Because the anadromous life-cycle of SJR Chinook salmon requires conveyance of juveniles from a riverine system to the Pacific Ocean to support the return of spawning adults, meeting this objective requires the consideration of environmental conditions and a connected river system. Though there are likely a multitude of environmental parameters that impact emigrating juvenile salmon, flow regime and predation are often cited as having a significant effect on travel speed and survivability (Raymond 1968; Berggren and Filardo1993; Michel et al. 2013). Flows in the SJR are highly regulated as means to support agricultural production, and non-native piscivorous fish in the restoration reach tend to occur more frequently downstream of Reach 1 (Gravelly Ford to confluence of Merced River; SJRRP 2013 I&M Report). Anecdotal evidence collected during SJRRP fish inventory and monitoring efforts suggests many of the non-native piscivores tend to reside in anthropogenic altered habitats (e.g., mine pits, altered channels, etc), which may pose a challenge to emigrating salmon. River flow conditions and water temperatures were managed during spring releases to elicit downstream fish movement with pulse flows and receding flows benches to avoid stranding. -

Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project Is Located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River

Hydropower Project License Summary STANISLAUS RIVER, CALIFORNIA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) Photo Credit: California State Water Board This summary was produced by the Hydropower Reform Coalition Stanislaus River, CA STANISLAUS RIVER, CA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) DESCRIPTION: The Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project is located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River. Owned. The project, operated by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), has an installed capacity of 87.9 MW and occupies approximately 1,060 acres of federal land within the Stanislaus National Forest. Both the Middle and South Forks are popular destinations for a variety of outdoor recreation activities. With a section of the lower river designated by the State of CA as a Wild Trout Fishery, the Middle Fork is widely considered to be one of California’s best wild trout fisheries. The South Fork on the other hand, with its high gradient and steep rapids, is a popular whitewater kayaking and rafting destination. A. SUMMARY 1. License application filed: December 26, 2002 2. License Issued: April 24, 2009 3. License expiration: March 31, 2047 4. Capacity: Spring Gap- 6.0 MW Stanislaus- 81.9 MW 5. Waterway: Middle & North Forks of the Stanislaus River 6. Counties: Calaveras, Tuolumne 7. Licensee: Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) 8. Licensee Contact: Pacific Gas and Electric Company P.O. Box 997300 Sacramento, CA 95899-7300 9. Project area: The project is located in the Sierra Nevada mountain range of north- central California. -

California's San Joaquin Valley: a Region and Its Children Under Stress

CALIFORNIA’S SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY: A REGION AND ITS CHILDREN UNDER STRESS January 2017 Commissioned by Study Conducted by California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Region and Its Children Under Stress January 2017 Dear Colleagues, We are pleased to share with you California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Region and its Children Under Stress, commissioned by the San Joaquin Valley Health Fund, with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Sierra Health Foundation, and prepared by the UC Davis Center for Regional Change. In preparing this report, researchers met with residents and those working with and on behalf of Valley communities to learn what their priorities are for policy and systems change. As detailed in the report, their quest for a more equitable region is focused on several priorities that include early education, healthy food, healthy living environments and equitable land use planning as the primary issues of concern. While the report documents the many racial, health and other inequities, and the particular effects they have on the lives and life chances of families raising children in the region, it also presents the vision of local leaders and community residents. We know the challenges that lie ahead will be difficult to address. While the San Joaquin Valley includes the top agricultural producing counties in California, almost 400,000 of the region’s children live in poverty and seven of the 10 counties with the highest child poverty rates in the state are in the Valley. One out of every four Valley children experiences food insecurity and they are much more likely to be exposed to pesticides while in school and to go to schools with unsafe drinking water.