Mongolia RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Briefing Paper Landmine Policy in South and East Asia and the Pacific July 2019

Briefing Paper Landmine Policy in South and East Asia and the Pacific July 2019 Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 2 Use, Production, Transfer, and Stockpiling .............................................................................................. 2 Landmine Contamination ........................................................................................................................ 3 Mine Ban Policy by Country ..................................................................................................................... 3 Afghanistan ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Australia .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Bangladesh ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Bhutan ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Brunei .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Cambodia........................................................................................................................................ -

Virtual Inauguration Ceremony of the Cyber Security Centre in Mongolia

Emerging Security Challenges Division Virtual Inauguration Ceremony of the Cyber Security Centre in Mongolia Science for Peace 18 January 2021 and Security (SPS) Programme About the Project Description The goal of this Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme project was to develop the cyber defence capabilities in the Mongolian Armed Forces. It achieved this by creating a Cyber Security Centre incorporating a Cyber Incident Response Capability (CIRC) for the Ministry of Defence and General Staff of the Mongolian Armed Forces. In addition, the project provided network administrators and cyber security staff with the necessary knowledge and training to operate the Cyber Security Centre and CIRC. Cyber defence experts from the NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA) have contributed to this project with support from the SPS Programme. The project was officially launched in July 2017 and ended in November 2020. Deliverables This project had the following main deliverables: • Building defence capacities of Mongolia through the establishment of a Cyber Security Center with supporting infrastructure at the Mongolian Ministry of Defence (MOD); • Providing specialized cyber defence training in network technology skills and CIRC-specific skills, as well as English language skills, to MOD personnel; • Providing technical advice for the design and integration of the cyber laboratory; • Providing necessary IT equipment for the cyber laboratory; • Providing assistance to the Mongolian Armed Forces in expanding cooperation with specialized institutions from NATO in the area of cyber defence, so as to develop and ensure their information security. Programme 09:00 - 09:25 Remarks Moderator: Mr. David van Weel, Assistant Secretary General, Emerging Security Challenges Division, NATO • H.E. -

Ubimaf-Catalog-Eng.Pdf

4TH ULAANBAATAR INTERNATIONAL MEDIA ART FESTIVAL MIGRATION Energy center, Dornogobi MN 17 Art gallery Centrel Museum of Playtime music festival Mongolian Dinosaurus 2019.06.21-23 2019.06.27-07.07 2019.07.05-07 2019.06.27 Organizer: Co-Organizer: Sponsors: Official partners: Supporters: Media partners: GREETING FROM ARTS COUNCIL OF MONGOLIA With high smartphone and internet users edition expands the festival’s scope with reaching 2.6 million in 2016 (Media Atlas. four different occasions being held over the Mongolia. 2016), Mongolia is considerably a course of the festival. The festival will open country with high technology consumers. with “Train Migration to Gobi” a mobile However, advancement of technology installation, performance and interactive and its use in the arts is underdeveloped. talks with 36 people on the train trip to Gobi Responding to this challenge, ACM initiated within the framework of Нүүдэл-movement Ulaanbaatar International Media Arts Festival aspect of migration. The idea is to focus on in 2016 with commitment to facilitating the movement part of migration and invite innovation, collaboration, strategic growth young artist, curators,and scholars to share and cultural impact for the media arts in their work and practice related to mobility. Mongolia and around the world and through Food migration will also be the main platform of forward-thinking and inclusive highlight of the journey and chef Kumar programs that hold space for a dynamic Bansal will share his story on food migration network of artists and organizations from India to Mongolia along with each committed to powerful creative storytelling participants story food migration. -

Investment in Mongolia

Investment in Mongolia KPMG in Mongolia 2016 Edition CONTENTS 1 COUNTRY OUTLINE 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Geography and climate 6 1.3 History 6 1.4 Political system 7 1.5 Population, language and religion 7 1.6 Currency 8 1.7 Public holidays 8 2 BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT 10 2.1 Mongolian economy overview 10 2.2 Economic trading partners 11 Exports 11 Imports 11 2.3 Business culture 11 2.4 Free trade zones 12 2.5 Foreign exchange controls 12 3 INVESTMENT CLIMATE FOR FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT 14 3.1 Foreign investment opportunities 14 3.2 Foreign investment legislation 14 3.3 Commencing business in Mongolia 15 Practical considerations 15 Registration 15 Mergers, acquisitions and restructurings 16 Exit strategy 16 3.4 Financing 17 3.5 Intellectual property 17 Copyright 17 Trademarks and trade names 17 Patents 18 4 REPORTING, AUDITING AND THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT 20 4.1 Financial reporting 20 4.2 Auditing 21 4.3 Regulatory environment 21 Competition law 21 © 2016 KPMG Audit LLC, the Mongolian member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. 2 / Investment in Mongolia Corporate governance 22 Land ownership and use 22 Anti-corruption law 23 Arbitration 23 5 TAXATION 25 5.1 General tax law 25 Overview 25 Rights and duties – taxpayers and tax authorities 26 Tax reporting and payments 26 Tax audits 26 Debt collection 27 5.2 Corporate tax 27 Overview of the corporate tax system 27 Taxable income 28 Losses 28 5.3 Transfer pricing 29 5.4 Double tax agreements -

MONGOLIA CONSTRAINTS ANALYSIS a Diagnostic Study of the Most Binding Constraints to Economic Growth in Mongolia

The production of this constraints analysis was led by the partner governments, and was used in the development of a Millennium Challenge Compact or threshold program. Although the preparation of the constraints analysis is a collaborative process, posting of the constraints analysis on this website does not constitute an endorsement by MCC of the content presented therein. 2014-001-1569-02 MONGOLIA CONSTRAINTS ANALYSIS A diagnostic study of the most binding constraints to economic growth in Mongolia August 18, 2016 Produced by National Secretariat for the Second Compact Agreement between the Government of Mongolia and the Millennium Challenge Corporation of the USA With technical assistance from the Millennium Challenge Corporation i Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ vi Glossary of Terms .......................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. -

Mongolian Defence Policy

MONGOLIAN DEFENCE POLICY Major Abai Kanad JCSP 45 PCEMI 45 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2019. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2019. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 45 – PCEMI 45 MAY 2019 – MAI 2019 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT MONGOLIAN DEFENCE POLICY Major Abai Kanad “This paper was written by a candidate “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes fulfilment of one of the requirements of the pour satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au document, and thus contains facts and cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions opinions which the author alone considered que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et appropriate and correct for the subject. It convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas does not necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion d'un opinion of any agency, including the organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the Canadian gouvernement du Canada et le ministère de la Department of National Defence. -

Mongolian European Chamber Of

MONGOL Since 1991 the MESSENGER 500 ¥ No. 07-08 (1076-1077) MONGOLIA’S FIRST ENGLISH WEEKLY PUBLISHED BY MONTSAME NEWS AGENCY Friday, February 17, 2012 Mongolia Economic Happy Tsagaan Sar! Forum planned for early March The Mongolian Economic Forum 2012 will run on March 5-6. At a February 10 press conference, organizers of the forum reported about the preparations and measures for the forum. As of information given by MP S. Oyun; Deputy Finance Minister Ch.Gankhuyag; Ch.Khashchuluun, head of the National Development and Innovation Committee; and P.Tsagaan, senior advisor to the President, the forum that is to be organized for the third time, will run this year under the motto ‘Together for Development’. The forum will have sub-meetings under themes on economic development, social policy and competitiveness, and bring together over 1000 foreign and domestic participants. During the forum, it is planned to publicly introduce Mongolia’s development forum until 2021 issued by Open Society. MP S. Oyun said, “In reality, why isn’t poverty decreasing while the economy has grown over the past five or six years. We believe that issues on how to decrease poverty and what should be done for the fruits of economic growth to improve livelihoods will develop into hot discussions during the forum. For instance, the statistical figures on poverty percentages are very confusing. The National Statistical Committee evaluates the poverty rate at 39 percent while the World Bank says it is lower using a different methodology to evaluate poverty. Therefore, -

Access to Finance: Developing the Microinsurance Market in Mongolia

Access to Finance Developing the Microinsurance Market in Mongolia Mongolia experienced a challenging transition from socialist economy to market economy from 1990 onwards. Its commercial insurance market is still at its infancy, with gross written premiums in 2013 amounting to only 0.54% of gross domestic production. ADB undertook this technical assistance study to support microinsurance development in Mongolia. The study provides an overview of the development of Mongolia’s insurance market in ACCESS TO FINANCE general and the microinsurance segment in particular, then identifies gaps in the insurance regulatory framework that need to be bridged to expand microinsurance coverage to more households. DEVELOPING THE MICROINSURANCE MARKET IN MONGOLIA About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. ISBN Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines ACCESS TO FINANCE DEVELOPING THE MICROINSURANCE MARKET IN MONGOLIA Access to Insurance Initiative Kelly Rendek and Martina Wiedmaier-Pfister © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

U.S.$5,000,000,000 GLOBAL MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAM the GOVERNMENT of MONGOLIA Bofa Merrill Lynch Deutsche Bank HSBC J.P. Morgan

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM U.S.$5,000,000,000 GLOBAL MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAM THE GOVERNMENT OF MONGOLIA Under this U.S.$5,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Program (the “Program”), the Government of Mongolia (the “Issuer”) may from time to time issue notes (the “Notes”) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined in “Subscription and Sale”). Notes may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively, “Bearer Notes” and “Registered Notes”). The aggregate nominal amount of all Notes to be issued under the Program will not exceed U.S.$5,000,000,000 or its equivalent in other currencies at the time of agreement to issue. The Notes and any relative Receipts and Coupons (as defined herein), will constitute direct, unconditional, unsubordinated and (subject to the Terms and Conditions of the Notes (the “Conditions”)) unsecured obligations of the Issuer and rank pari passu without any preference among themselves and (save for certain obligations required to be preferred by law) equally with all other unsecured and unsubordinated debt obligations of the Issuer. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers. References in this Information Memorandum to the relevant Dealer shall, in the case of an issue of Notes being (or intended to be) subscribed for by more than one Dealer, be to all Dealers agreeing to subscribe for such Notes. Approval in-principle has been granted for the listing and quotation of Notes that may be issued pursuant to the Program and which are agreed at or prior to the time of issue thereof to be so listed and quoted on the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (the “SGX-ST”). -

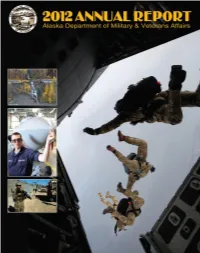

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Governor Sean Parnell Main photo: Commander in Chief Catching Air. Members of the Alaska Air National Guard’s 212th Rescue Squadron perform a free-fall jump from a 144th Airlift Squadron C-130 over the Malemute Drop Zone on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in October 2012. Photo: First Lieutenant Bernie Kale, DMVA Public Affairs From top to bottom: Disaster Strikes. A portion of the Alaska Railroad was washed out by heavy rains and high winds, which created disas- Major General Thomas H. Katkus ter conditions in many communities across the st ate in what Adjutant General, Alaska National Guard became known as the 2012 September Severe Storms. & Commissioner of the DMVA Photo: Courtesy of the Office of Governor Sean Parnell Cadet Confidence. Alaska Military Youth Academy cadet Cy Lewis of Anchorage tours the 3rd Maintenance Squadron, Fighter Aircraft Fuels System Repair Facility on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson and holds the nose of an F-22 Raptor in his fingertips. Photo: Roman Schara, Alaska Military Youth Academy Deployment Success. Sergeant Benjamin Angaiak, a secu rity force member from B Company, 1st Battalion (Airborne), 143rd Infantry Regiment, Alaska Army National Guard, assigned to Provincial Reconstruction Team Farah, provides security during a key leader engagement in Ms. Kalei Rupp Farah City, Farah province, Afghanistan, in September 2012. Photo: Lieutenant Benjamin Addison, U.S. Navy Managing Editor/DMVA Public Affairs DMVA Public Affairs Major Guy Hayes Reports: Second Lieutenant Bernie Kale Sergeant Balinda O’Neal For the People . .2 Alaska Army National Guard . .8 The Adjutant General . .3 Alaska Air National Guard . -

BDSEC JSC Weekly Market Update Mongolia’S Largest Broker December 7, 2020

BDSEC JSC Weekly Market Update Mongolia’s Largest Broker December 7, 2020 MSE Market Commentary MSE Top Movers • MSE Top-20 Index was up 0.42%, MSE A Index ended higher 0.18%, When will MSE delist some companies? (marketinfo.mn) and MSE B Index decreased 0.01% Market capitalization amounted to • Mongolian Stock Exchange was established 30 years ago, and 2,606.3 billion and average volume of 134,654 shares were traded at an currently 194 companies listed on MSE. Of which businesses of many Indexes Points % Change aggregate average value of MNT 20.4 million. companies have already been halted, some companies have not held MSE Top-20 Index 17.658.44 +0.42% • APU (APU) was the most actively traded stock with an aggregate value shareholders meeting and violated interest of their shareholders, of MNT 19.8 million. Following was Erdene Resource Dev. (ERDN) with and stocks of some companies have not been traded in the market. MSE A Index 8,117.58 +0.18% its total value of MNT 11.3 million. However, Mongolian Stock Exchange has not taken arrangement on MSE B Index 7,326.15 -0.01% • Tier 1 top gainers of the week were Mongolian Mortgage Corp. (MIK), the matter till now. LendMN (LEND), and Bayangol Hotel (BNG) on the other hand BDSec • Looking at the statistics of stock trading, stocks of 58% out of all Market Summary Value (USD) (BDS) lost as much as 8.07% of its value and closed at MNT 791.5. companies listed on MSE have not been traded on the market for last Market capitalization 914,491,673 Mongolia Headlines one year. -

East Asian Strategic Review 2019

East Asian Strategic Review 2019 East Asian Strategic Review 2019 The National Institute for Defense Studies, Japan ISBN978-4-86482-074-5 Printed in Japan East Asian Strategic Review 2019 The National Institute for Defense Studies Japan Copyright © 2019 by the National Institute for Defense Studies First edition: July 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form without written, prior permission from the National Institute for Defense Studies. This publication is an English translation of the original Japanese edition published in April 2019. EASR 2019 comprises NIDS researchers’ analyses and descriptions based on information compiled from open sources in Japan and overseas. The statements contained herein do not necessarily represent the official position of the Government of Japan or the Ministry of Defense. Edited by: The National Institute for Defense Studies 5-1 Ichigaya Honmura-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8808, Japan URL: http://www.nids.mod.go.jp Translated and Published by: Urban Connections Osaki Bright Core 15F, 5-15, Kitashinagawa 5-chome, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0001, Japan Phone: +81-3-6432-5691 URL: https://urbanconnections.jp/en/ ISBN 978-4-86482-074-5 The National Institute for Defense Studies East Asian Strategic Review 2019 Printed in Japan Cover photo Japan-India joint exercise (JIMEX18) (JMSDF Maritime Staff Office) Eighth Japan-Australia 2+2 Foreign and Defence Ministerial Consultations (Japan Ministry of Defense) F-35A fighter (JASDF Air Staff Office) Preface This edition of the East Asian Strategic Review (EASR) marks the twenty-third year of the flagship publication of the National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS), Japan’s sole national think tank in the area of security affairs.