Night Thoughts Romanticism Inaugurated a Lasting, If Embattled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock

Colby Quarterly Volume 30 Article 4 Issue 2 June June 1994 Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 30, no.2, June 1994, p.98-108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sturrock: Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William B Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market by JlTNE STURROCK IIyEA, THOUGH I walk through the valley ofthe shadow ofdeath, I shall fear no evil, for thou art with me, thy rod and thy staffthey comfort me." The twenty-third psalm has been offered as comfort to the sick and the grieving for thousands ofyears now, with its image ofGod as the good shepherd and the soul beloved ofGod as the protected sheep. This psalm, and such equally well-known passages as Isaiah's "He shall feed his flock as a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs in his arms" (40. 11), together with the specifically Christian version: "I am the good shepherd" (John 10. 11, 14), have obviously affected the whole pastoral tradition in European literature. Among othereffects the conceptofGod as shepherd has allowed for development of the protective implications of classical pastoral. The pastoral idyll-as opposed to the pastoral elegy suggests a safe, rural world in that corruption, confusion and danger are placed elsewhere-in the city. -

Introduction

Introduction The notes which follow are intended for study and revision of a selection of Blake's poems. About the poet William Blake was born on 28 November 1757, and died on 12 August 1827. He spent his life largely in London, save for the years 1800 to 1803, when he lived in a cottage at Felpham, near the seaside town of Bognor, in Sussex. In 1767 he began to attend Henry Pars's drawing school in the Strand. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver, making plates from which pictures for books were printed. He later went to the Royal Academy, and at 22, he was employed as an engraver to a bookseller and publisher. When he was nearly 25, Blake married Catherine Bouchier. They had no children but were happily married for almost 45 years. In 1784, a year after he published his first volume of poems, Blake set up his own engraving business. Many of Blake's best poems are found in two collections: Songs of Innocence (1789) to which was added, in 1794, the Songs of Experience (unlike the earlier work, never published on its own). The complete 1794 collection was called Songs of Innocence and Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. Broadly speaking the collections look at human nature and society in optimistic and pessimistic terms, respectively - and Blake thinks that you need both sides to see the whole truth. Blake had very firm ideas about how his poems should appear. Although spelling was not as standardised in print as it is today, Blake was writing some time after the publication of Dr. -

William Carlos Williams' Indian Son(G)

The News from That Strange, Far Away Land: William Carlos Williams’ Indian Son(g) Graziano Krätli YALE UNIVERSITY 1. In his later years, William Carlos Williams entertained a long epistolary relationship with the Indian poet Srinivas Rayaprol (1925-98), one of a handful who contributed to the modernization of Indian poetry in English in the first few decades after the independence from British rule. The two met only once or twice, but their correspondence, started in the fall of 1949, when Rayaprol was a graduate student at Stanford University, continued long after his return to India, ending only a few years before Williams’ passing. Although Williams had many correspondents in his life, most of them more important and better known literary figures than Rayaprol, the young Indian from the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh was one of the very few non-Americans and the only one from a postcolonial country with a long and glorious literary tradition of its own. More important, perhaps, their correspondence occurred in a decade – the 1950s – in which a younger generation of Indian poets writing in English was assimilating the lessons of Anglo-American Modernism while increasingly turning their attention away from Britain to America. Rayaprol, doubly advantaged by virtue of “being there” (i.e., in the Bay Area at the beginning of the San Francisco Renaissance) and by his mentoring relationship with Williams, was one of the very first to imbibe the new poetic idiom from its sources, and also one of the most persistent in trying to keep those sources alive and meaningful, to him if not to his fellow poets in India. -

Artist and Spectre: Divine Vision in the Earthly Work of William Blake

Artist and Spectre: Divine Vision in the Earthly Work of William Blake Robert Searway My first encounter with William Blake, best reading teachers available, a radical though perhaps not as magnificent as a fiery challenge to the reasoning mind, a training star descending to my foot (as Blake depicted ground for knowledge in as many areas as both his brother Robert’s and his own you are willing to open for yourself” (14). encounter with the poet Milton above), came Blake did, however, hope for understanding during my freshman year in college when my within his own lifetime. In an advertisement professor admitted he had not studied Blake for his last artistic exhibition, Blake implores extensively and did not fully understand him. the public: “those who have been told that my From that moment I was intrigued, and have Works are but an unscientific and irregular come to find that not understanding Blake has Eccentricity, a Madman’s Scrawls, I demand been and remains a common theme even of them to do me the justice to examine among English literature studies. Though he before they decide” (Complete Poetry 527- was considered mad and neglected artistically 528). Blake hoped to cultivate a new for much of his life, modern scholars have understanding of the human potential in begun to change his fortunes. Blake still has Imagination. He hoped to change perceptions something, even if only a fleeting confusing of reality, and believed in the power of art to vision, to offer in his art and idea of art. cultivate the minds of his audience. -

The Prophetic Books of William Blake : Milton

W. BLAKE'S MILTON TED I3Y A. G.B.RUSSELL and E.R.D. MACLAGAN J MILTON UNIFORM WirH THIS BOOK The Prophetic Books of W. Blake JERUSALEM Edited by E. R. D. Maclagan and A. G. B. Russell 6s. net : THE PROPHETIC BOOKS OF WILLIAM BLAKE MILTON Edited by E. R. D. MACLAGAN and A. G. B. RUSSELL LONDON A. H. BULLEN 47, GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1907 CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. INTRODUCTION. WHEN, in a letter to his friend George Cumberland, written just a year before his departure to Felpham, Blake lightly mentions that he had passed " nearly twenty years in ups and downs " since his first embarkation upon " the ocean of business," he is simply referring to the anxiety with which he had been continually harassed in regard to the means of life. He gives no hint of the terrible mental conflict with which his life was at that time darkened. It was more actually then a question of the exist- ence of his body than of the state of his soul. It is not until several years later that he permits us to realize the full significance of this sombre period in the process of his spiritual development. The new burst of intelle6tual vision, accompanying his visit to the Truchsessian Pi6lure Gallery in 1804, when all the joy and enthusiasm which had inspired the creations of his youth once more returned to him, gave him courage for the first time to face the past and to refledl upon the course of his deadly struggle with " that spe6lrous fiend " who had formerly waged war upon his imagination. -

Charlotte Smith's Life Writing Among the Dead

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LIFE WRITING VOLUME IX (2020) LW&D56–LW&D80 Un-earthing the Eighteenth-Century Churchyard: Charlotte Smith’s Life Writing Among the Dead James Metcalf King’s College London ABSTRACT The work of poet and novelist Charlotte Smith (1749–1806) has been consis- tently associated with life writing through the successive revelations of her autobiographical paratexts. While the life of the author is therefore familiar, Smith’s contribution to the relationship between life writing and death has been less examined. Several of her novels and poems demonstrate an awareness of and departure from the tropes of mid-eighteenth-century ‘graveyard poetry’. Central among these is the churchyard, and through this landscape Smith re- vises the literary community of the ‘graveyard school’ but also its conventional life writing of the dead. Reversing the recuperation of the dead through reli- gious, familial, or other compensations common to elegies, epitaphs, funeral sermons, and ‘graveyard poetry’, Smith unearths merely decaying corpses; in doing so she re-writes the life of the dead and re-imagines the life of living com- munities that have been divested of the humic foundations the idealised, famil- iar, localised dead provide. Situated in the context of churchyard literature and the churchyard’s long history of transmortal relationships, this article argues that Smith’s sonnet ‘Written in the Church-Yard at Middleton in Sussex’ (1789) intervenes in the reclamation of the dead through life writing to interrogate what happens when these consolatory processes are eroded. Keywords: Charlotte Smith, graveyard poetry, churchyard, death European Journal of Life Writing, Vol IX, 56–80 2020. -

The Way to Otranto: Gothic Elements

THE WAY TO OTRANTO: GOTHIC ELEMENTS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH POETRY, 1717-1762 Vahe Saraoorian A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1970 ii ABSTRACT Although full-length studies have been written about the Gothic novel, no one has undertaken a similar study of poetry, which, if it may not be called "Gothic," surely contains Gothic elements. By examining Gothic elements in eighteenth-century poetry, we can trace through it the background to Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, the first Gothic novel. The evolutionary aspect of the term "Gothic" itself in eighteenth-century criticism was pronounced, yet its various meanings were often related. To the early graveyard poets it was generally associated with the barbarous and uncouth, but to Walpole, writing in the second half of the century, the Gothic was also a source of inspiration and enlightenment. Nevertheless, the Gothic was most frequently associated with the supernatural. Gothic elements were used in the work of the leading eighteenth-century poets. Though an age not often thought remark able for its poetic expression, it was an age which clearly exploited the taste for Gothicism, Alexander Pope, Thomas Parnell, Edward Young, Robert Blair, Thomas and Joseph Warton, William Collins, Thomas Gray, and James Macpherson, the nine poets studied, all expressed notes of Gothicism in their poetry. Each poet con tributed to the rising taste for Gothicism. Alexander Pope, whose influence on Walpole was considerable, was the first poet of significance in the eighteenth century to write a "Gothic" poem. -

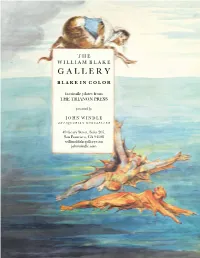

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Night Thoughts

DISCUSSION A Re-View of Some Problems in Understanding Blake’s Night Thoughts John E. Grant Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 18, Issue 3, Winter 1984-85, pp. 155- 181 PAGE 155 WINTER 1984-85 BLAKE/AS ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY prehensive project which seeks to explain and restore an but does not, however, achieve it. historical methodology to literary studies" (ix). Much of The Romantic Ideology, in fact, reads like an introduction reliant on generalizations that one hopes the author will 1 substantiate and perhaps qualify. I say this not to dismiss All of these critics, like McGann, regard Natural Superna- turalism as a canonical text. In "Rationality and Imagination in the book, only to indicate its limits. I sympathize with Cultural History," Critical Inquiry, 2 (Spring, 1976), 447-64—a McGann's desire to restore historical self-consciousness discussion of Natural Supernaturalism that McGann should acknowl- to Romantic scholarship and, more generally, to aca- edge—Abrams answers some of these critics and defends his omis- demic criticism. The Romantic Ideology affirms this goal sion of Byron. the proper forum for detailed discussion of several points I shall raise. Furthermore, some of the issues I shall DISCUSSION address extend beyond the specific problems of the Clar- with intellectual spears SLIODQ winged arrows of thought endon edition of Night Thoughts to larger questions of how Blake's visual works can be presented and under- stood. This re-view of the Clarendon edition should make it easier for readers to use the edition in ways that A Re-View of Some Problems in will advance scholarship on Blake's most extensive proj- ect of pictorial criticism. -

Sample Poem Book

The Lord is My Shepherd; I shall not Our Father which art in want. He maketh me to lie down in green heaven, Hallowed be thy I’d like the memory of me pastures; He leadeth me beside the still name. Thy kingdom come. To be a happy one, waters. He restoreth my soul. He leadeth I’d like to leave an afterglow me in the path of righteousness for His Thy will be done in earth, as it Of smiles when day is done. name’s sake. Yea, though I walk through is in heaven. Give us this day I’d like to leave an echo the valley of the shadow of death, I will Whispering softly down the ways, fear no evil; for Thou art with me; Thy our daily bread. And forgive Of happy times and laughing times rod and Thy staff they comfort me. Thou us our debts, as we forgive And bright and sunny days. preparest a table before me in the our debtors. And lead us not I’d like the tears of those who grieve presence of mine enemies. Thou To dry before the sun anointest my head with oil; my cup into temptation, but deliver us Of happy memories that I leave behind, runneth over. Surely goodness and from evil: For Thine is the When the day is done. mercy shall follow me all the days of my life; and I will dwell in the house of the kingdom, and the power, and -Helen Lowrie Marshall Lord forever. the glory, for ever. -

The Four Zoas Vala

THE FOUR ZOAS The torments of Love & Jealousy in The Death and Judgement of Albion the Ancient Man by William Blake 1797 Rest before Labour For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. (Ephesians 6: 12; King James version) VALA Night the First The Song of the Aged Mother which shook the heavens with wrath Hearing the march of long resounding strong heroic Verse Marshalld in order for the day of Intellectual Battle Four Mighty Ones are in every Man; a Perfect Unity John XVII c. 21 & 22 & 23 v Cannot Exist. but from the Universal Brotherhood of Eden John I c. 14. v The Universal Man. To Whom be Glory Evermore Amen και. εςηνωςεν. ηµιν [What] are the Natures of those Living Creatures the Heavenly Father only [Knoweth] no Individual [Knoweth nor] Can know in all Eternity Los was the fourth immortal starry one, & in the Earth Of a bright Universe Empery attended day & night Days & nights of revolving joy, Urthona was his name In Eden; in the Auricular Nerves of Human life Which is the Earth of Eden, he his Emanations propagated Fairies of Albion afterwards Gods of the Heathen, Daughter of Beulah Sing His fall into Division & his Resurrection to Unity His fall into the Generation of Decay & Death & his Regeneration by the Resurrection from the dead Begin with Tharmas Parent power. darkning in the West Lost! Lost! Lost! are my Emanations Enion O Enion We are become a Victim to the Living We hide in secret I have hidden Jerusalem in Silent Contrition O Pity Me I will build thee a Labyrinth also O pity me O Enion Why hast thou taken sweet Jerusalem from my inmost Soul Let her Lay secret in the Soft recess of darkness & silence It is not Love I bear to [Jerusalem] It is Pity She hath taken refuge in my bosom & I cannot cast her out. -

![Printed Performance and Reading the Book[S] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8900/printed-performance-and-reading-the-book-s-of-urizen-blakes-bookmaking-process-and-the-transformation-of-late-eighteenth-century-print-culture-2988900.webp)

Printed Performance and Reading the Book[S] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture

Colby Quarterly Volume 35 Issue 2 June Article 3 June 1999 Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation of Late Eighteenth- Century Print Culture John H. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 35, no.2, June 1999, p. 73-89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Jones: Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bo Printed Performance and Reading The Book[s] of Urizen: Blake's Bookmaking Process and the Transformation ofLate Eighteenth Century Print Culture by JOHN H. JONES NTIL RECENTLY, CRITICS have considered the textual problems in The U [First] Book of Urizen as impediments in their search for a definitive, synoptic edition of the poem. While eight copies of the poem are known to exist, each copy is unique for a variety of reasons, including missing plates, changes in plate order, inconsistencies with chapter and verse numbering, and individual plate alterations. About these difficulties Jerome McGann notes that no editors have been willing to pursue their quest for narrative consistency far enough so as to remove one or another of the duplicate chapters 4. Furthermore, all later editions enshrine the problem of this unstable text in that curious title-so difficult to read aloud-with the bracketed word: The [First] Book of Urizen.... Thus a residue of the text's "extraordinary inconsistency" always remains a dra matic presence in our received scholarly editions.