The Case of Tiong Bahru, Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAVOURING SINGAPORE This Urbane Island-State Is All About Its Sophisticated Fusion of Diverse Cuisines, Vibrant Cultures and Architectural Gems

TRAVEL TRAVEL SAVOURING SINGAPORE This urbane island-state is all about its sophisticated fusion of diverse cuisines, vibrant cultures and architectural gems. By Doug Wallace ity, state and country, all rolled into one Tamil — but you will also hear many other It’s also worth noting that, for a country that — Singapore, the chameleon nation of tongues, including the colloquial “Singlish.” has been evolving for centuries, Singapore boasts Southeast Asia, is many things all at once. This island nation is also an architect’s paradise, a surprising number of green spaces where Its colourful history as a trading settlement with cutting-edge skyscrapers coexisting with visitors and locals alike can saunter through influences all facets of modern life, colonial-era buildings meticulously revived and and relax. One of these is the Botanic Gardens, C harmoniously, in innovative ways. infused with modern elements. Streets are awash which showcases the world’s largest collection The population of 5.8 million is a vibrant in colour, thanks to the lively façades of the of orchids. Gardens by the Bay, a futuristic eco- mix of Chinese, Indian and Malay cultures iconic mixed-use traditional shophouses, where architectural park, features two biomes and a — Peranakans (locally born Singaporeans) retail stores are on the main floor and, above “forest” of tree-like towers covered with tropical The glittering Marina Bay skyline at descended from people who began immigrating them, one or two storeys of apartments. Well- flowers and ferns. In addition to running tracks sundown is an irresistable magnet for to the Malay Archipelago 400 years ago — preserved places of worship anchor almost every and dog-walking parks, as well as yoga and tai Instagram aficionados, whether they’re and more than 145 years of British rule left an neighbourhood, such as the Sri Mariamman, the chi class venues, these urban oases also offer a locals or first-time visitors to Singapore. -

Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in Medishield Life Scheme Last Updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board

1 Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in MediShield Life Scheme Last updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board PUBLIC HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Alexandra Hospital Admiralty Medical Centre Changi General Hospital Institute of Mental Health Jurong Medical Centre Khoo Teck Puat Hospital KK Women's And Children's Hospital National Cancer Centre National Dental Centre National Heart Centre Singapore National Skin Centre National University Hospital Ng Teng Fong General Hospital Singapore General Hospital Singapore National Eye Centre Sengkang General Health (Hospital) Tan Tock Seng Hospital PRIVATE HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Concord International Hospital Farrer Park Hospital Gleneagles Hospital Mt Alvernia Hospital Mt Elizabeth Hospital Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital Parkway East Hospital Raffles Hospital Pte Ltd Thomson Medical Centre DAY SURGERY CENTRES A Clinic For Women A Company For Women A L Lim Clinic For Women Pte Ltd Abraham’s Ear, Nose & Throat Surgery Pte Ltd Access Medical (Bedok South) Access Medical (Bukit Batok) Access Medical (Circuit Road) Access Medical (East Coast) Access Medical (Jurong West) Access Medical (Kim Keat) Access Medical (Marine Terrace) Access Medical (Redhill Close) Access Medical (Tampines 730) Access Medical (Toa Payoh) Access Medical (Whampoa) 2 Access Medical (Teck Ghee) Adult & Child Eye (ACE) Clinic Advance Surgical Group Advanced Centre For Reproductive Medicine Pte. Ltd. Advanced Medicine Imaging Advanced Urology (Parkway East Medical Center) Agape Women’s Specialists -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Auction & Sales Private Treaty

Auction & Sales Private Treaty. DECEMBER 2019: RESIDENTIAL Salespersons to contact: Tricia Tan, CEA R021904I, 6228 7349 / 9387 9668 Gwen Lim, CEA R027862B, 6228 7331 / 9199 2377 Noelle Tan, CEA R047713G, 6228 7380 / 9766 7797 Teddy Ng, CEA R006630G, 6228 7326 / 9030 4603 Lock Sau Lai, CEA R002919C, 6228 6814 / 9181 1819 Sharon Lee (Head of Auction), CEA R027845B, 6228 6891 / 9686 4449 Ong HuiQi (Admin Support) 6228 7302 Website: http://www.knightfrank.com.sg/auction Email: [email protected] LANDED PROPERTIES FOR SALE * Owner's ** Public Trustee's *** Estate's @ Liquidator's @@ Bailiff's % Receiver's # Mortgagee's ## Developer's ### MCST's Approx. Land / Guide Contact S/no District Street Name Tenure Property Type Room Remarks Floor Area (sqft) Price Person MORTGAGEE SALE One of the best location in Sentosa Cove with a picturesque waterway view. Leasehold 99 2½-Storey Bungalow Noelle / Upside potential. Foreigners are eligible to purchase landed properties only in # 1 D04 PARADISE ISLAND years wef. with Private Pool and 5- 5 7,045 / 8,170 $11.59M Sau Lai / Sentosa Cove. 5 ensuite bedrooms. Efficient layout. Private pool & yacht 07/11/2005 Bedrooms Sharon berth. Vacant possession. More Info MORTGAGEE SALE Leasehold 99 2½-Storey Detached Noelle / Scenic waterway view. Unique façade. Internal lift serving all levels. With # 2 D04 SANDY ISLAND years wef. House with Basement 7 7,307 / 6,727 $11.57M Sau Lai private pool and yacht berth. Basement parking with mechanized parking. 13/06/2007 Parking More Info MORTGAGEE SALE Leasehold 2½-Storey Detached Noelle / Lifestyle living with an enchanting waterway view! 4 ensuite bedrooms. -

851 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

851 bus time schedule & line map 851 Bt Merah Int View In Website Mode The 851 bus line (Bt Merah Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bt Merah Int: 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM (2) Yishun Int: 5:40 AM - 11:42 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 851 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 851 bus arriving. Direction: Bt Merah Int 851 bus Time Schedule 56 stops Bt Merah Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Monday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009) Tuesday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Blk 757 (59069) Wednesday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059) Thursday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM 612 Yishun Street 61, Singapore Friday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn (59049) Saturday 5:30 AM - 11:34 PM Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039) Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029) Lentor Ave - Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019) 851 bus Info Direction: Bt Merah Int Lentor Ave - Opp Bullion Pk Condo (55269) Stops: 56 Trip Duration: 92 min Lentor Ave - Opp Countryside Est (55259) Line Summary: Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009), Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Blk 757 (59069), Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059), Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn Lentor Ave - Bef Yio Chu Kang Rd (55249) (59049), Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039), Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029), Lentor Ave - Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Opp Castle Green (55179) Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019), Lentor Ave - Opp Bullion Pk Condo (55269), Lentor Ave - Opp Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Yio Chu Kang Stn (55189) Countryside -

175 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

175 bus time schedule & line map 175 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 175 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM (2) Lor 1 Geylang Ter: 6:00 AM - 11:26 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 175 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 175 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 175 bus Time Schedule 62 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 AM - 11:30 PM Monday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Lor 1 Geylang - Lor 1 Geylang Ter (80009) Lorong 1 Geylang Terminal, Singapore Tuesday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Lor 1 Geylang - Opp Blk 2c (80101) Wednesday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upp Boon Keng Rd - Geylang West Cc (80319) Thursday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upper Boon Keng Road, Singapore Friday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upp Boon Keng Rd - Aft Geylang West Cc (80309) Saturday 6:00 AM - 11:30 PM Upper Boon Keng Road, Singapore Geylang Bahru - Opp Blk 82 (80299) Kallang Bahru - Opp Blk 66 (60039) 175 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Kallang Bahru - Blk 16 (60029) Stops: 62 16 Kallang Place, Singapore Trip Duration: 95 min Line Summary: Lor 1 Geylang - Lor 1 Geylang Ter Kallang Bahru - Bendemeer Stn Exit B (60019) (80009), Lor 1 Geylang - Opp Blk 2c (80101), Upp Boon Keng Rd - Geylang West Cc (80319), Upp Boon Lavender St - Aft Kallang Bahru (07369) Keng Rd - Aft Geylang West Cc (80309), Geylang 103 Lavender Street, Singapore Bahru - Opp Blk 82 (80299), Kallang Bahru - Opp Blk 66 (60039), Kallang Bahru - Blk 16 (60029), Kallang Lavender St - Aperia/Bef Kallang -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

1 参考资料list of References 阿窿ā Lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽

参考资料 List of References 阿窿 ā lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽子凡(2008)。香港粤语惯用语研究。香港城市大学出版社。 吴昊(2006)。港式广府话研究(1)。次文化堂出版社。 Chan, K. S. (2005). One more story to tell: Memories of Singapore, 1930s-1980s. Landmark Books. Geisst, C. R. (2017). Loan sharks: The birth of predatory lending. Brookings Institution Press. Iskandar, T. (2005). Kamus dewan edisi keempat. Dewan Bahasa Dan Pustaka. 爱它死 ài tā sǐ 周清海(2002)。新加坡华语词与语法。玲子传媒私人有限公司。 Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Drugs and inhalants. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/drugs-and-inhalants. Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Misuse of Drugs Act. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/misuse-of-drugs-act. Holland, J. (2001). Ecstasy: The complete guide: A comprehensive look at the risks and benefits of MDMA. Park Street Press. Lee, T. K., et al. (1998). A 10-year review of drug seizures in Singapore. Medicine, Science and the Law, 38(4), 311-316. National Archives of Singapore. (1997). Keynote address by Mr Wong Kan Seng. Minister for Home Affairs at the 1997 National Seminar on drug abuse at Shangri-La Hotel. Retrieved on 16 October 2019: www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/1997040502/wks19970405s.pdf. 按柜金 àn guì jīn 邓贵华(2015 年 8 月 26 日)。较上届大选少约 10% 候选人竞选按柜金 1 万 4500 元。 联合早报。Retrieved on 12 September 2019: https://www.zaobao.com.sg/zpolitics/news/story20150826-518789. 湖南法制院(1912)、湖南调查局编(1911 年)、劳柏文校(清)。湖南民情风俗报 告书:湖南商事习惯报告书。湖南教育出版社,2010。 汪惠迪(1999)。时代新加坡特有词语词典。联邦出版社。 Elections Department. (2011). Parliamentary Elections Act (Chapter 218). -

List of Publicly Accessible Locations Where E-Bins Are Deployed*

List of publicly accessible locations where E-Bins are deployed* *This is a working list, more locations will be added every week* Name Location Type of Bin Placed Ang Mo Kio CC • Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Best Denki • 1 Harbourfront Walk, Vivocity, #2-07 • 3155 Commonwealth Avenue West, The Clementi Mall, #04-46/47/48/49 • 68 Orchard Road, Plaza Singapura, #3-39 • 2 Jurong East Street 21, IMM, #3-33 • 63 Jurong West Central 3, Jurong Point, #B1-92 • 109 North Bridge Road, Funan, #3-16 3-in-1 Bin • 1 Kim Seng Promenade, Great World City, #07-01 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • 391A Orchard Road, Ngee Ann City Tower A • 9 Bishan Place, Junction 8 Shopping Centre, #03-02 • 17 Petir Road, Hillion Mall, #B1-65 • 83 Punggol Central, Waterway Point • 311 New Upper Changi Road, Bedok Mall • 80 Marine Parade Road #03 - 29 / 30 Parkway Parade Complex Bugis Junction • 230 Victoria Street 3-in-1 Bin Towers (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Merah CC • 4000 Jalan Bukit Merah 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Panjang • 8 Pending Rd 3-in-1 Bin CC (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Cash • 135 Jurong Gateway Road Converters • 510 Tampines Central 1 3-in-1 Bin • Lor 4 Toa Payoh, Blk 192, #01-674 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • Ang Mo Kio Ave 8, Blk 710A, #01-2625 Causeway Point • 1 Woodlands Square 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Central Plaza • 298 Tiong Bahru Rd 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Challenger • 302 Tiong Bahru Road, Tiong Bahru Plaza, #03-19 • 1 Jurong West Central 2, Jurong Point, #B1-94 • 200 Victoria Street, Bugis Junction, #03-10E • 5 Changi Business -

Bank & Branch Code Guide

ACH BANK & BRANCH CODE GUIDEs Last updated: 20 September 2021 IMPORTANT NOTE: 1. This guide is for customer using the old IBG payment and collections. 2. Customer using the new FAST/GIRO service, please be reminded that the following 3 banks require the 3 digits branch code to be appended to the account number. OCBC – Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Limited HSBC – The Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited SBI – State Bank of India Please follow the instruction given in Appendix C for more information. 3. UOB will not be held responsible for any errors or omissions that may appear in the guide. For updates of the codes, please refer to www.uobgroup.com/ACHcodes. 4. For DBS enquiries, please call 1800 222 2200. For OCBC enquiries, please call 1800 438 3333. The ACH Bank Code, Branch Code and Account Number are key fields in the required information to be provided for Interbank GIRO (IBG) transactions only. For accounts belonging to the following banks, you may wish to take note of the following conditions when preparing the IBG transactions: Bank Bank Branch Account Remarks Name Code Code No (Example) - 10-digit Account No - Use first 3 digits of Account No and refer to Appendix A to retrieve the corresponding Branch Code UOB 7375 030 9102031012 eg. For account 9102031012, use 910 to refer to Appendix A to retrieve the Branch Code 030. (Account No will remain as 9102031012.) UOB 7375 001 860012349101 - VAN: Virtual Account Number (for VAN - Length of Account Number varies from 7 to account 18 digits (except 8, 10, 15 and 16) only) - Use 001 as default Branch Code - Usually 10-digit Account No - Use first 3 digits of Account No as the Branch Code DBS 7171 005 0052312891 eg. -

MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE HALAL DINING•PRAYERHALAL SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES to Singapore Your FOREWORD

Your MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE to Singapore HALAL DINING • PRAYER SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES FIRST EDITION | 2020 | ENGLISH VERSION EDITION | 2020 FIRST FOREWORD Muslim-friendly Singapore P18 LITTLE INDIA Muslims make up 14 percent of Singapore’s population As a Muslim traveller, this guide provides you and it is no surprise that this island state offers a large with the information you need to enjoy your stay variety of Muslim-friendly gastronomic experiences. in Singapore — a city where your passions in life MASJID SULTAN P10 KAMPONG GLAM Many of these have been Halal certified by MUIS, are made possible. You may also download the P06 ORCHARD ROAD also known as the Islamic Religious Council of MuslimSG app and follow @halalSG on Twitter for Singapore (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura). Visitors any Halal related queries while in Singapore. can also consider Muslim-owned food establishments throughout the city. Furthermore, mosques and – Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS) musollahs around the island allow you to fulfill your P34 ESPLANADE religious obligations while you are on vacation. TIONG BAHRU P22 TIONGMARKET BAHRU P26 CHINATOWN P34 MARINA BAY CONTENTS 05 TIPS 26 CHINATOWN ORCHARD 06 ROAD 30 SENTOSA KAMPONG MARINA BAY & MAP OF SEVEN 10 GLAM 34 ESPLANADE NEIGHBOURHOODS This Muslim-friendly guide to the seven main LITTLE TRAVEL P30 SENTOSA neighbourhoods around 18 INDIA 38 ITINERARIES Singapore helps you make the best of your stay. TIONG HALAL RESTAURANT 22 BAHRU 42 DIRECTORY Tourism Court This guide was developed with inputs from writers Nur Safiah 1 Orchard Spring Lane Alias and Suffian Hakim, as well as CrescentRating, a leading Singapore 247729 authority on Halal travel. -

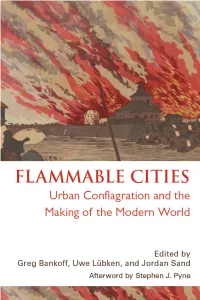

Flammable Cities: Urban Conflagration and the Making of The

F C Flammable Cities Urban Conflagration and the Making of the Modern World Edited by G B U L¨ J S T U W P Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the German Historical Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society at LMU Munich, Germany. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711–2059 uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2012 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flammable cities: Urban conflagration and the making of the modern world / edited by Greg Bankoff, Uwe Lübken, and Jordan Sand. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-299-28384-1 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-299-28383-4 (e-book) 1. Fires. 2. Fires—History. I. Bankoff, Greg. II. Lübken, Uwe. III. Sand, Jordan. TH9448.F59 2012 363.3709—dc22 2011011572 C Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 P : C F R 1 Jan van der Heyden and the Origins of Modern Firefighting: Art and Technology in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam 23 S D K 2 Governance, Arson, and Firefighting in Edo, 1600–1868 44 J S and S W 3 Taming Fire in Valparaíso, Chile, 1840s–1870s 63 S J.