Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0505234V1 11 May 2005 Eouini U Nesadn Fpaeaysses the Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAV Rundbrief Nr. 3 (2014)

BAV Rundbrief 2014 | Nr. 3 | 63. Jahrgang | ISSN 0405-5497 Bundesdeutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Veränderliche Sterne e.V. (BAV) BAV Rundbrief 2014 | Nr. 3 | 63. Jahrgang | ISSN 0405-5497 Table of Contents G. Maintz Revised elements of AP CVn and BH Ser 137 R. Gröbel Lightcurve and period of four RR Lyrae stars in Ursa Major: AG UMa, AV UMa, BK UMa and CK UMa 139 Inhaltsverzeichnis G. Maintz Verbesserte Elemente von AP CVn und BH Ser 137 R. Gröbel Lichtkurve und Periode von vier RR-Lyrae-Sternen in Ursa Major: AG UMa, AV UMa, BK UMa und CK UMa 139 Beobachtungsberichte D. Böhme Ist MP Gem ein Bedeckungsveränderlicher? 146 E. Pollmann / Zwischenergebnisse der 28-Tau-Kampagne 149 W. Vollmann F. Vohla U Orionis - ein (B-R)-Schelm 152 K. Wenzel Visuelle Lichtkurve von S5 0716+71 für den Beobachtungszeit- raum von August 2013 bis April 2014 154 K. Bernhard / Datamining leicht gemacht: Onlinekataloge für Einsteiger 155 S. Hümmerich Aus der Literatur Uni Bonn Spektakuläre Doppelexplosion am Sternenhimmel 161 E. Wischnewski Beobachtungsaufruf für Eta Orionis 163 Aus der BAV D. Bannuscher Neuigkeiten aus dem BAV-Vereinsleben 164 BAV-Vorstand BAV-Tagung Programmpunkte 165 D. Bannuscher Veränderlichenbeobachter-Treffen 2014 in Hartha 167 J. Hübscher Die systematische Überwachung veränderlicher Sterne durch BAV-Beobachter 170 W. Braune Veränderliche Sterne in „Sterne und Weltraum“ 174 T. Lange Rudolf Obertrifter ist verstorben 175 P. Reinhard Erlebnisbericht Namibia 2014 176 Aus den Sektionen F. Walter Bericht der Sektion „Bedeckungsveränderliche“ 2012 - 2014 178 G. Maintz Bericht der Sektion RR-Lyrae-Sterne 2012 - 2014 179 G. Monninger Bericht der Sektion Delta-Scuti-Sterne 2012 - 2014 180 R. -

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

Winter Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory Winter Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye NGC 457 CASSIOPEIA eta Cas Look for Notice how the constellations 5 the ‘W’ swing around Polaris during shape the night Is Dubhe yellowish compared 2 Polaris to Merak? Dubhe 3 Merak URSA MINOR Kochab 1 Is Kochab orange Pherkad compared to Polaris? THE PLOUGH 4 Mizar Alcor Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in winter. North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. To your right is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan standing up on it’s handle. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The top two stars are called the Pointers. Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white-hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you to the left, to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the right are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. Check with binoculars. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 2.0 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad mark the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. -

Rochester Skies

A S T R O N O M Y Rochester Skies First Newsletter ¨ Freezing Star-Party ¨ March Over Rochester ¨ Constellation Prize Rochester Astronomy Club Newsletter Issue #1 Winter ‘06 RAC Grows Up Constellation Prize Star Party The Rochester Astron- From our favorite Our coldest month omy Club has been meeting segment, turns out one of growing. As the size Randy Hemann will our best attended increases, so do the lead us by the optics Star Parties. Dean possibilities. If you are through the constel- Johnson fills us in on curious what RAC is lation Hydra, point- Eagle Bluff January. all about, take a look at ing out deep sky gems “Who We Are...” along the way. Page 1 Page 3 Page 4 ing to feel some growing pains. First Newsletter We appreciate feedback and Rochester Skies Welcome to the first newsletter of the encourage participation. If you Contents Rochester Astronomy Club. We hope have ideas, articles or images, March Over Rochester Pg 2 you find it fun and informative. You please submit them. Hunting the Hunter Pg 8 might even want to keep it around— It’s a Little Known Fact Pg 11 could be worth something someday! “Rochester Skies In the Beginning is a newsletter by the Pg 11 We hope this newsletter will be- club, for the club.” Satellite Satellbright Pg 10 come a source of anticipation for Up-Coming Events Pg 12 our members. As we ramp up If you have questions, comments or material for the Rochester Skies newsletter, our editorial process, we are go- please contact our lead editor Duane Deal at [email protected] A. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = Easy = Not Too Difficult = Difficult but Possible

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = easy = not too difficult = difficult but possible 1. Sigma Cassiopeiae (STF 3049). 23 hr 59.0 min +55 deg 45 min This system is tight but very beautiful. Use a high magnification (150x or more). Primary: 5.2, yellow or white Seconary: 7.2 (3.0″), blue 2. Eta Cassiopeiae (Achird, STF 60). 00 hr 49.1 min +57 deg 49 min This is a multiple system with many stars, but I will restrict myself to the brightest one here. Primary: 3.5, yellow. Secondary: 7.4 (13.2″), purple or brown 3. 65 Piscium (STF 61). 00 hr 49.9 min +27 deg 43 min Primary: 6.3, yellow Secondary: 6.3 (4.1″), yellow 4. Psi-1 Piscium (STF 88). 01 hr 05.7 min +21 deg 28 min This double forms a T-shaped asterism with Psi-2, Psi-3 and Chi Piscium. Psi-1 is the uppermost of the four. Primary: 5.3, yellow or white Secondary: 5.5 (29.7), yellow or white 5. Zeta Piscium (STF 100). 01 hr 13.7 min +07 deg 35 min Primary: 5.2, white or yellow Secondary: 6.3, white or lilac (or blue) 6. Gamma Arietis (Mesarthim, STF 180). 01 hr 53.5 min +19 deg 18 min “The Ram’s Eyes” Primary: 4.5, white Secondary: 4.6 (7.5″), white 7. Lambda Arietis (H 5 12). 01 hr 57.9 min +23 deg 36 min Primary: 4.8, white or yellow Secondary: 6.7 (37.1″), silver-white or blue 8. -

THE ORION CONSTELLATION the Great Hunter Orion Constellation Lies in the Northern Sky, on the Celestial Equator

THE ORION CONSTELLATION the Great Hunter Orion constellation lies in the northern sky, on the celestial equator. It is one of the brightest and best known constellations in the night sky. Orion is also known as the Hunter: it is associated with one in mythology. The constellation represents the mythical hunter Orion, who is often depicted in star maps as either facing the charge of Taurus, the bull, or chasing after the hare (constellation Lepus) with his two hunting dogs, represented by the nearby constellations Canis Major and Canis Minor. The constellation contains two of the ten brightest stars in the sky – Rigel (Beta Orionis) and Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) – a number of famous nebulae – the Orion Nebula, De Mairan’s Nebula and the Horsehead Nebula, among others, and one of the most prominent asterisms in the night sky – Orion’s Belt. FACTS • Orion is the 26th constellation in size, occupying an area of 594 square degrees. • It is located in the first quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ1) and can be seen at latitudes between +85° and -75°. • The neighboring constellations are Eridanus, Gemini, Lepus, Monoceros and Taurus. • Orion contains three Messier objects – M42, (NGC 1976) The Orion Nebula, M43, (NGC 1982) De Mairan’s Nebula, and M78, (NGC 2068) • It has seven stars with known planets. • There are two meteor showers associated with Orion, the Orionids and the Chi Orionids. The Orionid meteor shower reaches its peak around October 21 every year • Orion belongs to the Orion family of constellations, along with Canis Major, Canis Minor, Lepus and Monoceros MYTH The constellation Orion has its origins in Sumerian mythology, specifically in the myth of Gilgamesh. -

Betelgeuse and the Crab Nebula

The monthly newsletter of the Temecula Valley Astronomers Feb 2020 Events: General Meeting : Monday, February 3rd, 2020 at the Ronald H. Roberts Temecula Library, Room B, 30600 Pauba Rd, at 7:00 PM. On the agenda this month is “What’s Up” by Sam Pitts, “Mission Briefing” by Clark Williams then followed by a presentation topic : “A History of Palomar Observatory” by Curtis Oort Cloud in Perspective. Credit NASA / JPL- Croulet. Refreshments by Chuck Caltech Dyson. Please consider helping out at one of the many Star Parties coming up over the next few months. For General information: the latest schedule, check the Subscription to the TVA is included in the annual $25 Calendar on the web page. membership (regular members) donation ($9 student; $35 family). President: Mark Baker 951-691-0101 WHAT’S INSIDE THIS MONTH: <[email protected]> Vice President: Sam Pitts <[email protected]> Cosmic Comments Past President: John Garrett <[email protected]> by President Mark Baker Treasurer: Curtis Croulet <[email protected]> Looking Up Redux Secretary: Deborah Baker <[email protected]> Club Librarian: Vacant compiled by Clark Williams Facebook: Tim Deardorff <[email protected]> Darkness Star Party Coordinator and Outreach: Deborah Baker by Mark DiVecchio <[email protected]> Betelgeuse and the Crab Nebula: Stellar Death and Rebirth Address renewals or other correspondence to: Temecula Valley Astronomers by David Prosper PO Box 1292 Murrieta, CA 92564 Send newsletter submissions to Mark DiVecchio th <[email protected]> by the 20 of the month -

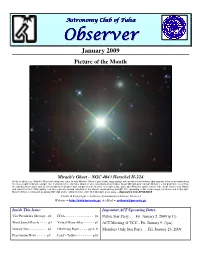

Observer Page 2 of 12

AAAssstttrrrooonnnooomyyy CCCllluuubbb ooofff TTTuuulllsssaaa OOOOOObbbbbbsssssseeeeeerrrrrrvvvvvveeeeeerrrrrr January 2009 Picture of the Month Mirach’s Ghost – NGC 404 / Herschel II-224 As far as ghosts go, Mirach's Ghost isn't really that scary. In fact, Mirach's Ghost is just a faint, fuzzy galaxy, well known to astronomers, that happens to be seen nearly along the line-of-sight to Mirach, a bright star. Centered in this star field, Mirach is also called Beta Andromedae. About 200 light-years distant, Mirach is a red giant star, cooler than the Sun but much larger and so intrinsically much brighter than our parent star. In most telescopic views, glare and diffraction spikes tend to hide things that lie near Mirach and make the faint, fuzzy galaxy look like a ghostly internal reflection of the almost overwhelming starlight. Still, appearing in this sharp image just above and to the right, Mirach's Ghost is cataloged as galaxy NGC 404 and is estimated to be some 10 million light-years away. – Explanation from APOD/NASA Credit & Copyright – Anthony Ayiomamitis (Athens, Greece) Website = http://www.perseus.gr/ & eMail = [email protected] Inside This Issue: Important ACT Upcoming Dates: Vice President's Message - p2 IYoA - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - p6 Public Star Party… Fri. January 2, 2009 (p11) Word Search Puzzle - - - - p3 Virtual Moon Atlas - - - - - - p7 ACT Meeting @ TCC - Fri. January 9, ( 7pm ) January Stars - - - - - - - - p4 Observing Pages - - - - pp 8- 9 Members Only Star Party … Fri. January 23, 2009 Planetarium News - - - - - p5 Land’s Tidbits - - - - - - - - p10 ACT Observer Page 2 of 12 Vice President’s Message by Tom Mcdonough Happy New Year to everyone, we have a very exciting year ahead of us! 2009 is the International Year of Astronomy in celebration of the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s observations of the heavens with one of the first telescopes. -

Astronomical League

Astronomical League 1 Table of Contents Eta Cassiopeiae (U) 3 Kappa Puppis 9 Rho Herculis 15 65 Piscium Zeta Cancri Nu Draconis Psi 1 Piscium Iota Cancri Psi Draconis Zeta Piscium 38 Lyncis 40/41 Draconis Gamma Arietis (U) Alpha Leonis 95 Herculis Lambda Arietis Gamma Leonis (U) 70 Ophiuchi Alpha Piscium 4 54 Leonis 10 Epsilon Lyrae (U) 16 Gamma Andromedae (U) N Hydrae Zeta Lyrae Iota Trianguli Delta Corvi Beta Lyrae Alpha Ursae Minoris 24 Comae Berenices Struve 2404 Gamma Ceti Gamma Virginis Otto Struve 525 Eta Persei 32 Camelopardalis Theta Serpentis Struve 331 5 Alpha Canum Ven. 11 Beta Cygni (U) 17 32 Eridani Zeta Ursae Majoris (U) 57 Aquilae Chi Tauri Kappa Bootis 31 Cygni 1 Camelopardalis Iota Bootis Alpha Capricorni 55 Eridani Pi Bootis Beta Capricorni Beta Orionis Epsilon Bootis Gamma Delphini (U) 118 Tauri 6 Alpha Librae 12 61 Cygni 18 Delta Orionis Xi Bootis Beta Cephei Struve 747 Delta Bootis Struve 2816 Lambda Orionis Mu Bootis Epsilon Pegasi Theta 1 Orionis (U) Delta Serpentis Xi Cephei Iota Orionis Zeta Coronae Borealis Zeta Aquarii Theta 2 Orionis 7 Xi Scorpii 13 Delta Cephei (U) 19 Sigma Orionis Struve 1999 8 Lacertae Zeta Orionis Beta Scorpii (U) 94 Aquarii Gamma Leporis Kappa Herculis Sigma Cassiopeiae Theta Aurigae Nu Scorpii Epsilon Monocerotis Sigma Coronae Borealis Beta Monocerotis (U) 8 16/17 Draconis 14 12 Lyncis Mu Draconis Epsilon Canis Majoris Alpha Herculis Delta Geminorum Delta Herculis 19 Lyncis 36 Ophiuchi Alpha Geminorum Omicron Ophiuchi The 12 stars marked with a (U) are also required for the AL Urban Club. -

Sigma Orionisorionis

CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review MIRCMIRC ObservationsObservations ofof thethe O-starO-star TripleTriple SigmaSigma OrionisOrionis Gail Schaefer Doug Gies John Monnier Nils Turner CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review New Title: Do NPOI and CHARA Orbits Agree? .... stay tuned.... CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review SigmaSigma OrionisOrionis Image credit: Peter Wienerroither CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationAssociation • Members of Orion OB1 sub-associations as defined by Brown et al. (2004) • Mainly OB stars plotted with a few AF stars Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationAssociation • Members of Orion OB1 sub-associations as defined by Brown et al. (2004) σ Ori • Mainly OB stars plotted with a few AF stars Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationsAssociations Orion OB1a (open squares) ~ 10 Myr old Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationsAssociations Orion OB1c (filled circles) Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationsAssociations Orion Nebula Cluster ~ 1 Myr Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review OrionOrion OB1OB1 AssociationsAssociations Orion OB1b (small dots) ~ 2-3 Myr Sherry et al. 2004 CHARA/NPOI 2013 Science & Technology Review SigmaSigma OrionisOrionis σ Ori A - 09.5V (Aa+Ab) σ Ori B - B0.5V (0.26") σ Ori C - A2V σ Ori D - B2V σ Ori -

Space Traveler 1St Wikibook!

Space Traveler 1st WikiBook! PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 25 Jan 2013 01:31:25 UTC Contents Articles Centaurus A 1 Andromeda Galaxy 7 Pleiades 20 Orion (constellation) 26 Orion Nebula 37 Eta Carinae 47 Comet Hale–Bopp 55 Alvarez hypothesis 64 References Article Sources and Contributors 67 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 69 Article Licenses License 71 Centaurus A 1 Centaurus A Centaurus A Centaurus A (NGC 5128) Observation data (J2000 epoch) Constellation Centaurus [1] Right ascension 13h 25m 27.6s [1] Declination -43° 01′ 09″ [1] Redshift 547 ± 5 km/s [2][1][3][4][5] Distance 10-16 Mly (3-5 Mpc) [1] [6] Type S0 pec or Ep [1] Apparent dimensions (V) 25′.7 × 20′.0 [7][8] Apparent magnitude (V) 6.84 Notable features Unusual dust lane Other designations [1] [1] [1] [9] NGC 5128, Arp 153, PGC 46957, 4U 1322-42, Caldwell 77 Centaurus A (also known as NGC 5128 or Caldwell 77) is a prominent galaxy in the constellation of Centaurus. There is considerable debate in the literature regarding the galaxy's fundamental properties such as its Hubble type (lenticular galaxy or a giant elliptical galaxy)[6] and distance (10-16 million light-years).[2][1][3][4][5] NGC 5128 is one of the closest radio galaxies to Earth, so its active galactic nucleus has been extensively studied by professional astronomers.[10] The galaxy is also the fifth brightest in the sky,[10] making it an ideal amateur astronomy target,[11] although the galaxy is only visible from low northern latitudes and the southern hemisphere.