Lahr Buscemi Fact.L.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Courts Act Review

OPEN COURTS ACT REVIEW The Hon. Frank Vincent AO QC September 2017 The consultations and submissions process of the Open Courts Act Review was confidential. The final report has been revised to the limited extent necessary to publish contributors’ views with their consent. Minor amendments were also made to clarify expression without making any material changes. Review of the Open Courts Act 2013 Table of Contents Review of the Open Courts Act 2013 .............................................................................................. 1 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 2 Summary of Recommendations ............................................................................................... 9 2.1 Presumption or principle? ................................................................................................. 9 2.2 A broader context ............................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1 Harmonising related areas of the law ......................................................................... 9 2.2.2 Unifying the law across jurisdictions ........................................................................... 9 2.3 Reforming the Open Courts Act ........................................................................................ 9 2.3.1 The duty to give reasons ........................................................................................... -

Modeling Annotators a Generative Approach to Annotators Are Useful

Zaidan & Eisner – Modeling ModelingAnnotators Annotators: Zaidan & Eisner – Modeling Annotators A Generative Approach to Annotators are useful. Learning from Annotator Rationales They provide us with data sets that we use everyday in the context of statistical learning. Omar F. Zaidan Jason Eisner Annotators are smart! ☺ The Center for Language We achieve good performance using such data in and Speech Processing many NLP tasks. Johns Hopkins University Annotators are underutilized… EMNLP 2008 – Honolulu, HI A lot of thought goes into annotation, but little of that is th Saturday October 25 , 2008 captured. {ozaidan |jason} @cs.jhu.edu Zaidan & Eisner – Modeling Annotators Zaidan & Eisner – Modeling Annotators Annotators are Underutilized? Annotators are Underutilized! م اب ,Hey annotator, Armageddon “Hey annotator“ ها ا ار ه آر . ا، إاج is this review This disaster flick is a disaster alright. Directed by is this review Tony Scott (Top Gun), it's the story of an asteroid the ت ( ج ب ) ، وي آ positive or size of Texas caught on a collision course with Earth. positive or و س ام ة ار . negative?” After a great opening, in which an American negative?” ا را، ء أ، إ إ spaceship, plus NYC, are completely destroyed by a رك، ا اآ و . comet shower, NASA detects said asteroid and go ن ا ا ( وس و ) ، :Annotator says: into a frenzy. They hire the world's best oil driller Annotator says (Bruce Willis), and send him and his crew up into و و إ اء ح ا ه. .space to fix our global problem ه ارة واآ و و ي The action scenes are over the top and too ludicrous آت، إ وت أ، و for words. -

This Thing of Ours Youtube

This thing of ours youtube Maverick Movies. Nicholas Santini (Danny Provenzano) is a young man trying to earn his “button” as a full. This Thing of Ours. armando chico. Loading Unsubscribe from armando chico? Cancel Unsubscribe. This Thing of Ours Trailer. This Thing of Ours is a crime/drama film released in starring Frank Vincent. Using the internet and old school mafia traditions, a crew of young gangsters led by Nicholas "Nicky" Santini. This Thing Of Ours frank vincent. jasongmar This shinebox of ours. Read more Let me tell you a couple of. Nicholas Santini (Danny Provenzano) is a young man trying to earn his button as a full-fledged member of the. Movie trailer for Mafia Film: This Thing of Ours Starring Danny Provenzano, Frank Vincent, and Vincent. Provided to YouTube by CDBaby This Thing of Ours · Geriko Triarchy ℗ Geriko Released on: When Danny agrees, Nicky - along with his partner and friend Johnny "Irish" Kelly - use violence and murder. "This Thing of Ours" from "Beauty Is " The Final Sessions Visit for more. Provided to YouTube by The Orchard Enterprises This Thing of Ours · Ray Price Beauty Is The Final. AND TESLAS GHOST) - THIS THING OF OURS (THE PRELUDE) The Sopranos: This Thing Of Ours (Own An Era) THE SOPRANOS teems with the mindless commerce and. The Sopranos "This Thing Of Ours" trailer. Montage by Lyle from This Thing of Ours Mafia Movie english movie part 3 - Duration: Horst Januk 10, views · The. Frank Vincent Gattuso (born August 4, ), known professionally as Frank Vincent, is an American actor. I gotta make a fuckin' living, they wanna fuckin' eat. -

Frameworks for the Downtown Arts Scene

ACADEMIC REGISTRAR ROOM 261 DIVERSITY OF LONDON 3Ei’ ATE HOUSE v'Al i STREET LONDON WC1E7HU Strategy in Context: The Work and Practice of New York’s Downtown Artists in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s By Sharon Patricia Harper Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art at University College London 2003 1 UMI Number: U602573 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602573 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The rise of neo-conservatism defined the critical context of many appraisals of artistic work produced in downtown New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Although initial reviews of the scene were largely enthusiastic, subsequent assessments of artistic work from this period have been largely negative. Artists like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf have been assessed primarily in terms of gentrification, commodification, and political commitment relying upon various theoretical assumptions about social processes. The conclusions reached have primarily centred upon the lack of resistance by these artists to post industrial capitalism in its various manifestations. -

![Bradley Whitford and Rob Lowe [Intro Music]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7234/bradley-whitford-and-rob-lowe-intro-music-407234.webp)

Bradley Whitford and Rob Lowe [Intro Music]

The West Wing Weekly 4.06: “Game On” Guests: Bradley Whitford and Rob Lowe [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to The West Wing Weekly, where it is a very special and exciting day. JOSH: A Very Special Episode…of Blossom. HRISHI: I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: You may know Joshua Malina from such things as this episode. JOSH [laughter]: Oh, man. Is there gonna be a lot of this? HRISHI: How did it feel to watch yourself on screen for the first time? JOSH: I’m almost embarrassed to admit I had butterflies in my stomach when I watched it. HRISHI: That’s great. JOSH: And it wasn’t nerves or anything, it’s literally like I was tying in organically to the excitement of that job and getting that job. I didn’t expect it at all. But yeah, that was like a very special time of my life, and as I started to watch it I just got, like, chills. HRISHI: You had a Proustian moment? JOSH: Yeah, exactly. HRISHI: You were transported. That’s great. In this episode, of course, we’re talking about “Game On.” It’s episode six from season four. JOSH: It was written by Aaron Sorkin and Paul Redford. It was directed by Alex Graves, and it first aired on October 30, 2002. HRISHI: This episode is a famous one because it features President Bartlet debating Governor Ritchie. There’s also some stuff about Qumar, there’s some stuff about Toby and Andy, but the real headline is that baby-faced Joshua Malina makes his first appearance as Will Bailey, who’s running the Horton Wilde campaign from a mattress store in Newport Beach. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

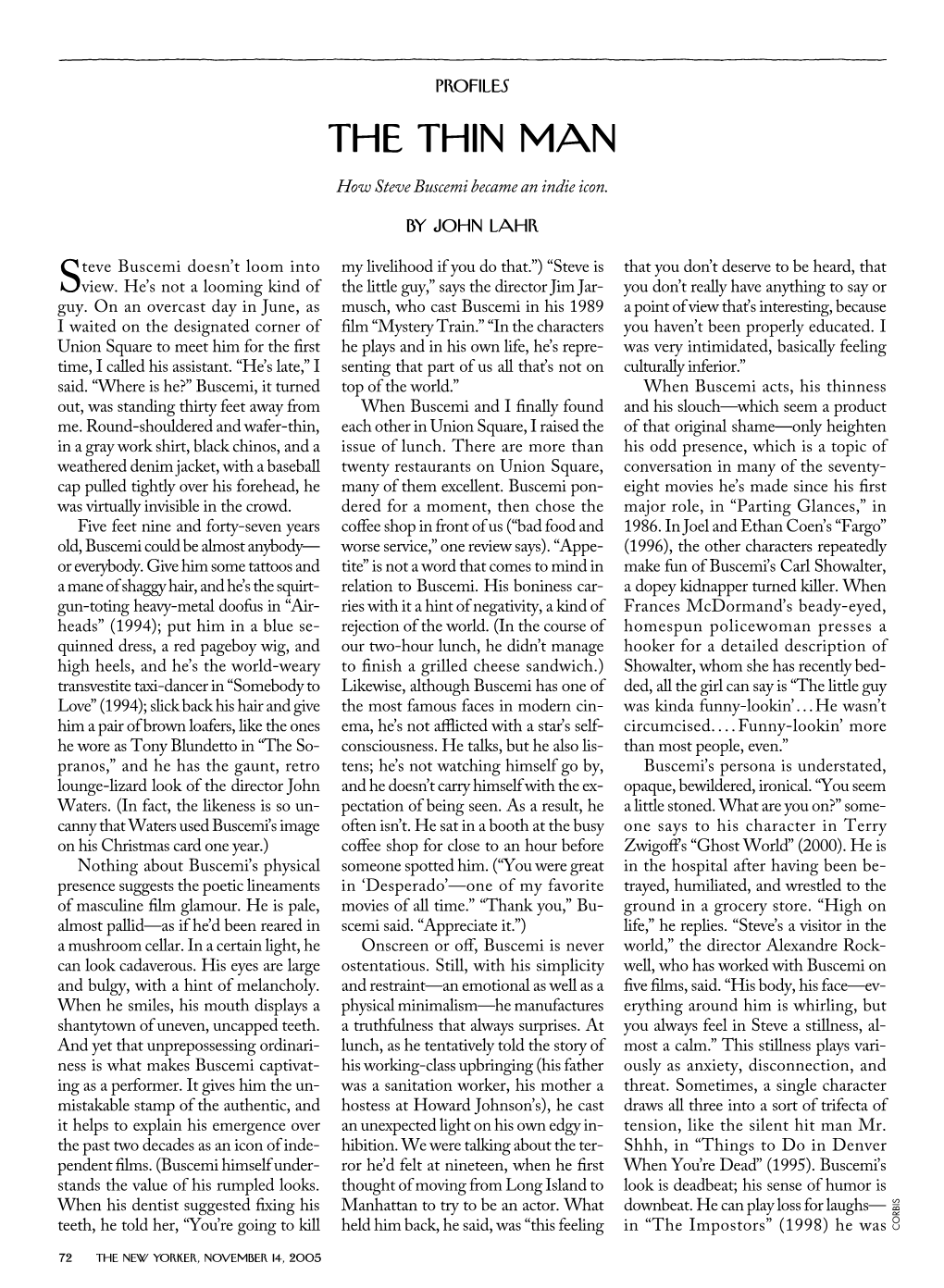

Working Class

>>brief encounters Indie poster boy Steve Buscemi on filmmaking, celebrity culture, and putting out fires By Harlan Jacobson There are endless things to say about Buscemi, closing in on 50 later this year— from his early days as a stand-up come- dian in the East Village in the Eighties to his work both in front of and behind the camera on The Sopranos to his still unre- alized dream project, an adaptation of William Burroughs’s Queer—and it’s a lit- tle odd interviewing him about Interview. In the real world, Buscemi is hard to reach, doesn’t do much publicity, wouldn’t meet in person—in short, the whole process of setting up the interview took on many of the trappings of how art and media have been derailed by celebrity culture, which of course is at the heart of Interview. Get him on the phone, or see him at Sundance responding to audience questions, how- ever, and he’s a straight shooter, earnest and open. The face of the new indepen- dent and quasi-independent American cinema for nearly 20 years, he remembers where he came from when the gates finally swing open. Before his murder Van Gogh was planning to remake Interview in English.Why did you step in? I didn’t know his work at all. Bruce Weiss, the producer, called me about the project, explaining that Theo wanted to remake Working Class Act three of his own films in the States, and that they were trying to honor that using steve buscemi’s career is an american spin-off of the American directors. -

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706 FILM FATALE Personal Hair Stylist to Hillary Swank Director: Deon Taylor ANT-MAN AND THE WASP Department Head Director: Peyton Reed Cast: Hannah John-Karmen, Paul Rudd, Judy Greer DEN OF THEIVES Department Head; Personal Hair Stylist to Gerard Butler Director: Christian Gudegast Cast: Gerard Butler, Dawn Olivieri SUBURBICON Personal Hair Stylist to Julianne Moore Director: George Clooney SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING Department Head Director: Jon Watts Cast: Tom Holland, Michael Keaton, Marisa Tomei, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jon Favreau, Laura Harrier, Tyne Daley KEEP WATCHING Department Head Director: Sean Carter Cast: Bella Thorne GHOST IN THE SHELL Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Rupert Saunders CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE WINTER Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson SOLDIER Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CHEF Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Jon Favreau WISH I WAS HERE Department Head Director: Zach Braff Cast: Zach Braff, Kate Hudson, Ashley Greene, Josh Gad, Mandy Patinkin, Joey King DON JON Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Joseph Gordon-Levitt THE MILTON AGENCY Jeri Baker 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 WE BOUGHT A ZOO Assistant Department Head Director: Cameron Crowe Cast: Thomas Haden Church, Elle Fanning BUTTER Assistant Department Head Director: Jim Field Smith Cast: Hugh Jackman, Alicia Silverstone, Ty Burrell SUPER 8 Assistant Department Head Director: J.J. Abrams Cast: Kyle Chandler, Jessica Tuck PEEP WORLD Department Head Director: Barry W. -

![“President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [Ad Insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’Re Listening to the West Wing Weekly](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1282/president-bartlet-special-guest-martin-sheen-ad-insert-intro-music-hrishi-you-re-listening-to-the-west-wing-weekly-841282.webp)

“President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [Ad Insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’Re Listening to the West Wing Weekly

The West Wing Weekly 4.00: “President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [ad insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And mine is Joshua Malina. This is a very special episode of Blossom, no, of The West Wing Weekly. We finally got to sit down with Martin Sheen and so we decided to celebrate. Let’s give him his own episode. The man deserves it. Hrishi and I were planning originally to pair our talk with Martin with our own conversation about the season opener “20 Hours in America” but then we decided to make an executive decision and give the president his own episode of the podcast. We hope you enjoy it. We think you will. HRISHI: Thank you so much for finding time to speak with us. MARTIN: I’m delighted. HRISHI: We actually have some gifts for you. MARTIN: You do? HRISHI: We do. Every president has a challenge coin and so we thought that President Bartlet deserves one too. MARTIN: Oh my…Thank you… HRISHI: [crosstalk] so here’s one. MARTIN: Look at that! Wow! Bartlet’s Army…ohh! Look at that…Do you know someone did a survey on the show for all of our seven years and do you know what the most frequent phrase was? “Hey.” ALL: [laughter] JOSH: That’s funny. That’s Sorkin’s legacy MARTIN: Exactly. How often do you remember saying it? I mean, did you ever do an episode where you didn’t say “hey” to somebody? JOSH: [crosstalk] That’s funny. -

Download Detailseite

Berlinale 2007 INTERVIEW Panorama INTERVIEW INTERVIEW Regie: Steve Buscemi USA/Niederlande 2007 Darsteller Pierre Peders Steve Buscemi Länge 81 Min. Katya Sienna Miller Format 35 mm, 1:1.77 Robert Peders Michael Buscemi Farbe Maggie Tara Elders Maitre’d David Schechter Stabliste Kellnerin Molly Griffith Buch David Schechter Restaurantgäste Elizabeth Bracco Steve Buscemi, James Villemaire nach dem Film von Fan Jackson Loo Theo van Gogh, dem Fahrer Doc Dougherty Original dreh buch Kommentatorin Donna Hanover von Theodor Holman Schauspieler Wayne Wilcox und einer Idee von Politexperte Danny Schechter Hans Teeuwen Autogrammjäger Philippe Vonlanthen Kamera Thomas Kist Yan Xi Kameraassistenz M. Autumn Eakin Schnitt Kate Williams Ton Jeff Pullman Musik Evan Lurie Production Design Loren Weeks Sienna Miller Ausstattung Christina Tonkin Requisite Pastor Alvarado Kostüm Vicki Farrell INTERVIEW Maske Maya Hardinge Der Film von Steve Buscemi ist der erste Teil einer Trilogie, die auf Arbeiten Casting Shelia Jaffe Theo van Goghs basiert. Als der niederländische Regisseur am 2. November Herstellungsltg. Mark Kamine 2004 von einem religiösen Fundamentalisten ermordet wurde, war ein eng - Aufnahmeleitung Christopher Johnston lischsprachiges Remake seines Films INTERVIEW mit amerikanischen Schau - Produzenten Bruce Weiss Gijs van de spielern unter van Goghs Regie bereits in Erwägung gezogen worden. Westelaken Nunmehr werden Remakes von zwei weiteren Filmen unter der Regie von Executive Producers Nick Stiliades Stanley Tucci und Bob Balaban folgen. Ellen Verbeek INTERVIEW schildert die Begegnung des Journalisten Pierre Peders mit dem Co-Executive Boyd Willat jungen Starlet Katya während eines Interviewtermins, bei dem sich Frager Producers Bob Savage Nanette Lepore und Befragte intensiver kennen lernen, als dies von beiden beabsichtigt Al Miller war. -

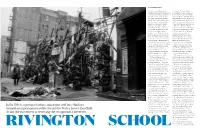

In the 1980S, a Group of Artists, Musicians and Free Thinkers Formed

Words Andy Thomas In 1986, if you walked east along discussions. They overlooked Rivington Street, in New York’s Lower everything that was not strictly for East Side, you would be confronted profit and tried to pretend it didn’t by a hulk of metal that twisted into exist,” says Kantor. “While highbrow the air like a giant spider hauling museum scholars wrote their essays itself from the earth. It was welded on auction winners, bestsellers and together, over many dope-fuelled gallery favourites, we had parties in nights, by a collection of artists, abandoned buildings and empty lots.” musicians and outsiders known Although critics and cultural as the Rivington School, who had historians overlooked the Rivington salvaged the abandoned cars and School, it was an important strand scrap metal that littered their to 1980s New York art. “It might neighbourhood. They christened sound contradictory, but the it the Rivington Sculpture Garden. Rivington School was not part A year later it was bulldozed by the of the downtown art scene,” says city, eager to capitalise on the area’s Kantor. “The downtown art scene property boom – which in turn was mostly meant the East Village driven by the art scene at the end of wannabe galleries and nightclubs, the street, where artists such as Keith seeking recognition and money, Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat dominated by fashion and cheap were gaining international glamour. The Rivington School recognition. Visit the corner of was a guerrilla-style art community Rivington and Forsyth today and camping in the ruins of a remote you’ll find luxury condos, built in area in the Lower East Side.” 1988, worth millions of dollars. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir.