Fire and Fire Ecology: Concepts and Principles Mark A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Extinguisher Booklet

NY Fire Consultants, Inc. NY Fire Safety Institute 481 Eighth Avenue, Suite 618 New York, NY 10001 (212) 239 9051 (212) 239 9052 fax Fire Extinguisher Training The Fire Triangle In order to understand how fire extinguishers work, you need to understand some characteristics of fire. Four things must be present at the same time in order to produce fire: 1. Enough oxygen to sustain combustion, 2. Enough heat to raise the material to its ignition temperature, 3. Some sort of fuel or combustible material, and 4. The chemical, exothermic reaction that is fire. Oxygen, heat, and fuel are frequently referred to as the "fire triangle." Add in the fourth element, the chemical reaction, and you actually have a fire "tetrahedron." The important thing to remember is: take any of these four things away, and you will not have a fire or the fire will be extinguished. Essentially, fire extinguishers put out fire by taking away one or more elements of the fire triangle/tetrahedron. Fire safety, at its most basic, is based upon the principle of keeping fuel sources and ignition sources separate Not all fires are the same, and they are classified according to the type of fuel that is burning. If you use the wrong type of fire extinguisher on the wrong class of fire, you can, in fact, make matters worse. It is therefore very important to understand the four different fire classifications. Class A - Wood, paper, cloth, trash, plastics Solid combustible materials that are not metals. (Class A fires generally leave an Ash.) Class B - Flammable liquids: gasoline, oil, grease, acetone Any non-metal in a liquid state, on fire. -

Spring Is on the Horizon! Before the Rains Clear and the Wildflowers Pop

PAGE 2 Upcoming Events. PAGE 3 Tree School Lane & Land Stewards Course Douglas County Master Woodland Managers inspecting a downed tree for bark beetles and wood borers. Photo by Alicia Christiansen, OSU Extension. PAGE 4 Choosing the Right Service Provider: Consulting Forester Spring is on the horizon! Before the rains clear and the wildflowers pop, take PAGE 5 advantage of time spent indoors to do some forest management planning Starker Lecture Series for the upcoming dry season. Are you looking to hire a consulting forester to complete a timber cruise or administer a harvest on your land this summer? PAGE 6 (check out page 4) Maybe you’re considering venturing into the world of So you want to grow Christmas tree farming. Converting to Christmas trees requires a lot of Christmas trees? What you planning, so be sure to read the article on page 6. We’ve got some good need to know before you news in store about log prices, get the scoop on trends on page 8! plant. Of course, we should appreciate the season we are in, so take advantage of PAGE 8 all the wonderful classes and workshops coming up in Douglas and Lane We’ve got a good feeling: Counties while it’s still soggy outside. From Tree School to Rural Living Day Logs & Non-timber Forest to Fire Preparedness, we’ve got you covered so you’re ready for anything Products - Prices & Trends that comes your way in 2020 and beyond. PAGE 9 May your spring be productive and your forest healthy! Congratulations Douglas County 2019 Master Alicia & Lauren Douglas & Lane County Extension Foresters Woodland Manager Graduates! Oregon State University Extension Service prohibits discrimination in all its programs, services, activities, and materials on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. -

Fire Ecology of the Valdivian Rain Forest*

Proceedings: 8th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1968 Fire Ecology of the Valdivian Rain Forest* E. J. WILHELM, JR. University of Virginia ALTHOUGH less widespread than formerly, there exists perhaps nowhere in Latin America a better example of a tem perate-marine forest than in the Lake District of southern Chile and Argentina. This forest reaches its optimum growth on the slopes of the Chilean watershed between 39° and 42° S (Fig. 1). Here thrives the exuberant plant community known as the Valdivian rain forest. The extraordinary growth of trees and shrubs, the thick stands of bamboo, the imposing lianas artistically twisting round the trunks of the massive beeches, and the luxuriant upholstering of epiphytes recall impressions of the tropical rain forest (Fig. 2). The sole purpose .in presenting this paper is to emphasize how man, through the agency of fire, has drastically altered the Valdivian rain forest ecosystem, and to conclusively show that most ruthless forest destruction has occurred in the past 75 years. BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE RAIN FOREST With just reason, the rain forest has been designated by Dimitri • Data for this paper were collected during a 1961-62 field investigation to Patagonia, Argentina-Chile. The research project was sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, Foreign Field Research Program, and financed by the Geography Branch, Office of Naval Research under contract number Nonr-2300 (09). 55 E. J. WILHELM, JR. VALDIVIAN RAIN FOREST o Former Distribution 1 ~ Present (1961) 36° Distribution ( ~ Data Taken "From Lerman ..:i ;IICI 1962 n Q 20 40 J: \ KM. -

Pyrogeography: the Where, When, and Why of Fire on Earth Philip Higuera, Assistant Professor, CNR, University of Idaho REM 244 Guest Lecture, 2 Feb., 2012

Pyrogeography: the where, when, and why of fire on Earth Philip Higuera, Assistant Professor, CNR, University of Idaho REM 244 Guest Lecture, 2 Feb., 2012 Bowman et al. 2009. Outline for Today’s Class 1. What is pyrogeography? 2. What can you infer from the pattern of fire? 3. Application – How will fire change with climate? What is biogeography? The study of life across space and through time: what do we see, where, and why? The view from Crater Peak, in Washington’s North Cascades 3 Solifluction lobes in Alaska’s Brooks Range Fire boundary in Montana’s Bitter Root Mountains What is pyrogeography? The study of fire across space and through time: what do we see, where, and why? The view from Crater Peak, in Washington’s North Cascades 4 Solifluction lobes in Alaska’s Brooks Range Fire boundary in Montana’s Bitter Root Mountains Fact: Energy released during a fire comes from stored energy in chemical bonds Implication: Fire at all scales is regulated by rates of plant growth University of Idaho Experimental Forest, 2009 What else does fire need to exist? 2006 wildfire, Yukon Flats NWR, Alaska Pyrogeographic framework: “fire” as an organism At multiple scales, the presence of fire depends upon the coincidence of: (1) Consumable resources (2) Atmospheric conditions (3) Ignitions Outline for Today’s Class 1. What is pyrogeography? 2. What can you infer from the pattern of fire? 3. Application – How will fire change with climate? Global patterns of fire – what can we infer? Fires per year (Bowman et al. 2009) . 80-86% of global area burned: grassland and savannas, primarily in Africa, Australia, and South Asia and South America Krawchuk et al., 2009, PLoS ONE: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0005102 Global patterns of fire – what can we infer? Net primary productivity (Bowman et al. -

FIGHTING FIRE with FIRE: Can Fire Positively Impact an Ecosystem?

FIGHTING FIRE WITH FIRE: Can Fire Positively Impact an Ecosystem? Subject Area: Science – Biology, Environmental Science, Fire Ecology Grade Levels: 6th-8th Time: This lesson can be completed in two 45-minute sessions. Essential Questions: • What role does fire play in maintaining healthy ecosystems? • How does fire impact the surrounding community? • Is there a need to prescribe fire? • How have plants and animals adapted to fire? • What factors must fire managers consider prior to planning and conducting controlled burns? Overview: In this lesson, students distinguish between a wildfire and a controlled burn, also known as a prescribed fire. They explore multiple controlled burn scenarios. They explain the positive impacts of fire on ecosystems (e.g., reduce hazardous fuels, dispose of logging debris, prepare sites for seeding/planting, improve wildlife habitat, manage competing vegetation, control insects and disease, improve forage for grazing, enhance appearance, improve access, perpetuate fire- dependent species) and compare and contrast how organisms in different ecosystems have adapted to fire. Themes: Controlled burns can improve the Controlled burns help keep capacity of natural areas to absorb people and property safe while and filter water in places where fire supporting the plants and animals has played a role in shaping that that have adapted to this natural ecosystem. part of their ecosystems. 1 | Lesson Plan – Fighting Fire with Fire Introduction: Wildfires often occur naturally when lightning strikes a forest and starts a fire in a forest or grassland. Humans also often accidentally set them. In contrast, controlled burns, also known as prescribed fires, are set by land managers and conservationists to mimic some of the effects of these natural fires. -

Session 611 Fire Behavior Ppt Instructor Notes

The Connecticut Fire Academy Unit 6.1 Recruit Firefighter Program Chapter 6 Presentation Instructor Notes Fire Behavior Slide 1 Recruit Firefighter Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program 1 Slide 2 © Darin Echelberger/ShutterStock, Inc. CHAPTER 6 Fire Behavior Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 3 Some have said that fires in modern furnished Fires Are Not Unpredictable! homes are unpredictable • A thorough knowledge of fire behavior will help you predict fireground events Nothing is unpredictable, firefighters just need to know what clues to look for Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 4 Connecticut Fire Academy Recruit Program CHEMISTRY OF COMBUSTION Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program 1 of 26 Revision: 011414 The Connecticut Fire Academy Unit 6.1 Recruit Firefighter Program Chapter 6 Presentation Instructor Notes Fire Behavior Slide 5 A basic understanding of how fire burns will give a Chemistry firefighter the ability to choose the best means of • Understanding the • Fire behavior is one of chemistry of fire will the largest extinguishment make you more considerations when effective choosing tactics Fire behavior and building construction are the basis for all of our actions on the fire ground Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 6 What is Fire? • A rapid chemical reaction that produces heat and light Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 7 Types of Reactions Exothermic Endothermic • Gives off heat • Absorbs heat Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 8 Non-flaming -

Prescribed Fire: the Fuels Component

FORESTRY Prescribed Fire: The Fuels Component ► In this second of a four-part series, you will learn the importance of the fuel component in prescribed fire. A common science experiment in grade school is to light a candle, place a glass jar over the candle, and watch the flame go out as the oxygen is consumed. This demonstrates the fire triangle of heat, oxygen, and fuel (figure 1). A prescribed fire is a working example of the principles of the fire triangle. In conducting a prescribed fire, you are either working to move a fire across the land or working to extinguish a fire. In either case, good fire lines are critical for containing the fire within a specific area (figure 2). Fire lines remove the fuel side of the fire triangle. Without the fuel, there is no heat and the fire goes out. Figure 1. The three components needed for a fire to occur are oxygen, heat, and fuel. These make up what is called the fire triangle. Remove one of the Fuel Components sides from this triangle and a fire cannot occur or will be extinguished. The way a fire burns depends on a number of Fuel Volume characteristics of the fuel. An often forgotten component The volume of fuel in the area affects the behavior of is the predominant species of the fuel. Not all grasses the fire and the amount of smoke it produces. Large burn the same; neither do all hardwood leaves or even volumes of fuel pose a significant risk for creating a pine needles. -

The Role of Old-Growth Forests in Frequent-Fire Landscapes

Copyright © 2007 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Binkley, D., T. Sisk, C. Chambers, J. Springer, and W. Block. 2007. The role of old-growth forests in frequent-fire landscapes. Ecology and Society 12(2): 18. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/ iss2/art18/ Synthesis, part of a Special Feature on The Conservation and Restoration of Old Growth in Frequent-fire Forests of the American West The Role of Old-growth Forests in Frequent-fire Landscapes Daniel Binkley 1, Tom Sisk 2,3, Carol Chambers 4, Judy Springer 5, and William Block 6 ABSTRACT. Classic ecological concepts and forestry language regarding old growth are not well suited to frequent-fire landscapes. In frequent-fire, old-growth landscapes, there is a symbiotic relationship between the trees, the understory graminoids, and fire that results in a healthy ecosystem. Patches of old growth interspersed with younger growth and open, grassy areas provide a wide variety of habitats for animals, and have a higher level of biodiversity. Fire suppression is detrimental to these forests, and eventually destroys all old growth. The reintroduction of fire into degraded frequent-fire, old-growth forests, accompanied by appropriate thinning, can restore a balance to these ecosystems. Several areas require further research and study: 1) the ability of the understory to respond to restoration treatments, 2) the rate of ecosystem recovery following wildfires whose level of severity is beyond the historic or natural range of variation, 3) the effects of climate change, and 4) the role of the microbial community. In addition, it is important to recognize that much of our knowledge about these old-growth systems comes from a few frequent-fire forest types. -

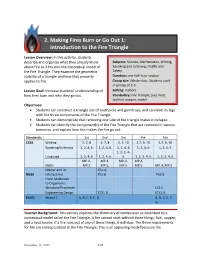

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

Fire Ecology of Ponderosa Pine and the Rebuilding of Fire-Resilient Ponderosa Pine Ecosystems 1

Fire Ecology of Ponderosa Pine and the Rebuilding of Fire-Resilient Ponderosa Pine Ecosystems 1 Stephen A. Fitzgerald2 Abstract The ponderosa pine ecosystems of the West have change dramatically since Euro-American settlement 140 years ago due to past land uses and the curtailment of natural fire. Today, ponderosa pine forests contain over abundance of fuel, and stand densities have increased from a range of 49-124 trees ha-1 (20-50 trees acre-1) to a range of 1235-2470 trees ha-1 (500 to 1000 stems acre-1). As a result, long-term tree, stand, and landscape health has been compromised and stand and landscape conditions now promote large, uncharacteristic wildfires. Reversing this trend is paramount. Improving the fire-resiliency of ponderosa pine forests requires understanding the connection between fire behavior and severity and forest structure and fuels. Restoration treatments (thinning, prescribed fire, mowing and other mechanical treatments) that reduce surface, ladder, and crown fuels can reduce fire severity and the potential for high-intensity crown fires. Understanding the historical role of fire in shaping ponderosa pine ecosystems is important for designing restoration treatments. Without intelligent, ecosystem-based restoration treatments in the near term, forest health and wildfire conditions will continue to deteriorate in the long term and the situation is not likely to rectify itself. Introduction Historically, ponderosa pine ecosystems have had an intimate and inseparable relationship with fire. No other disturbance has had such a re-occurring influence on the development and maintenance of ponderosa pine ecosystems. Historically this relationship with fire varied somewhat across the range of ponderosa pine, and it varied temporally in concert with changes in climate. -

Ecological Role of Fire

NCSR Education for a Sustainable Future www.ncsr.org Ecological Role of Fire NCSR Fire Ecology and Management Series Northwest Center for Sustainable Resources (NCSR) Chemeketa Community College, Salem, Oregon DUE # 0455446 Published 2008 Funding provided by the National Science Foundation opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the foundation 1 Fire Ecology and Management Series This six-module series is designed to address both the general role of fire in ecosystems as well as specific wildfire management issues in forest ecosystems. The series includes the following modules: • Ecological Role of Fire • Historical Fire Regimes and their Application to Forest Management • Anatomy of a Wildfire - the B&B Complex Fires • Pre-Fire Intervention - Thinning and Prescribed Burning • Post-Wildfire (Salvage) Logging – the Controversy • An Evaluation of Media Coverage of Wildfire Issues The Ecological Role of Fire introduces the role of wildfire to students in a broad range of disciplines. This introductory module forms the foundation for the next four modules in the series, each of which addresses a different aspect of wildfire management. An Evaluation of Media Coverage of Wildfire Issues is an adaptation of a previous NCSR module designed to provide students with the skills to objectively evaluate articles about wildfire-related issues. It can be used as a stand-alone module in a variety of natural resource offerings. Please feel free to comment or provide input. Wynn W. Cudmore, Ph.D., Principal Investigator Northwest Center for Sustainable Resources Chemeketa Community College P.O. Box 14007 Salem, OR 97309 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ncsr.org Phone: 503-399-6514 2 NCSR curriculum modules are designed as comprehensive instructions for students and supporting materials for faculty. -

Historical Pyrogeography of Texas, Usa

Fire Ecology Volume 10, Issue 3, 2014 Stambaugh et al.: Historical Pyrogeography doi: 10.4996/fireecology.1003072 Page 72 RESEARCH ARTICLE HISTORICAL PYROGEOGRAPHY OF TEXAS, USA Michael C. Stambaugh1*, Jeffrey C. Sparks2, and E.R. Abadir1 1 Department of Forestry, University of Missouri, 203 ABNR Building, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA 2 State Parks Wildland Fire Program, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 12016 FM 848, Tyler, Texas 75707, USA * Corresponding author: Tel.: +001-573-882-8841; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT RESUMEN Synthesis of multiple sources of fire La síntesis de múltiples fuentes de informa- history information increases the pow- ción sobre historia del fuego, incrementa el er and reliability of fire regime charac- poder de confiabilidad en la caracterización de terization. Fire regime characterization regímenes de fuego. La caracterización de es- is critical for assessing fire risk, identi- tos regímenes es crítica para determinar el fying climate change impacts, under- riesgo de incendio, identificar impactos del standing ecosystem processes, and de- cambio climático, entender procesos ecosisté- veloping policies and objectives for micos, y desarrollar políticas y objetivos para fire management. For these reasons, el manejo del fuego. Por esas razones, hici- we conducted a literature review and mos una revisión bibliográfica y un análisis es- spatial analysis of historical fire inter- pacial de los intervalos históricos del fuego en vals in Texas, USA, a state with diverse Texas, EEUU, un estado con diversos ambien- fire environments and significant tes de fuego y desafíos importantes en el tema fire-related challenges. Limited litera- de incendios. La literatura que describe regí- ture describing historical fire regimes menes históricos de fuego es limitada, y muy exists and few studies have quantita- pocos estudios han determinado cuantitativa- tively assessed the historical frequency mente la frecuencia histórica de fuegos de ve- of wildland fire.