Bioshock Infinite (2K Games, 2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

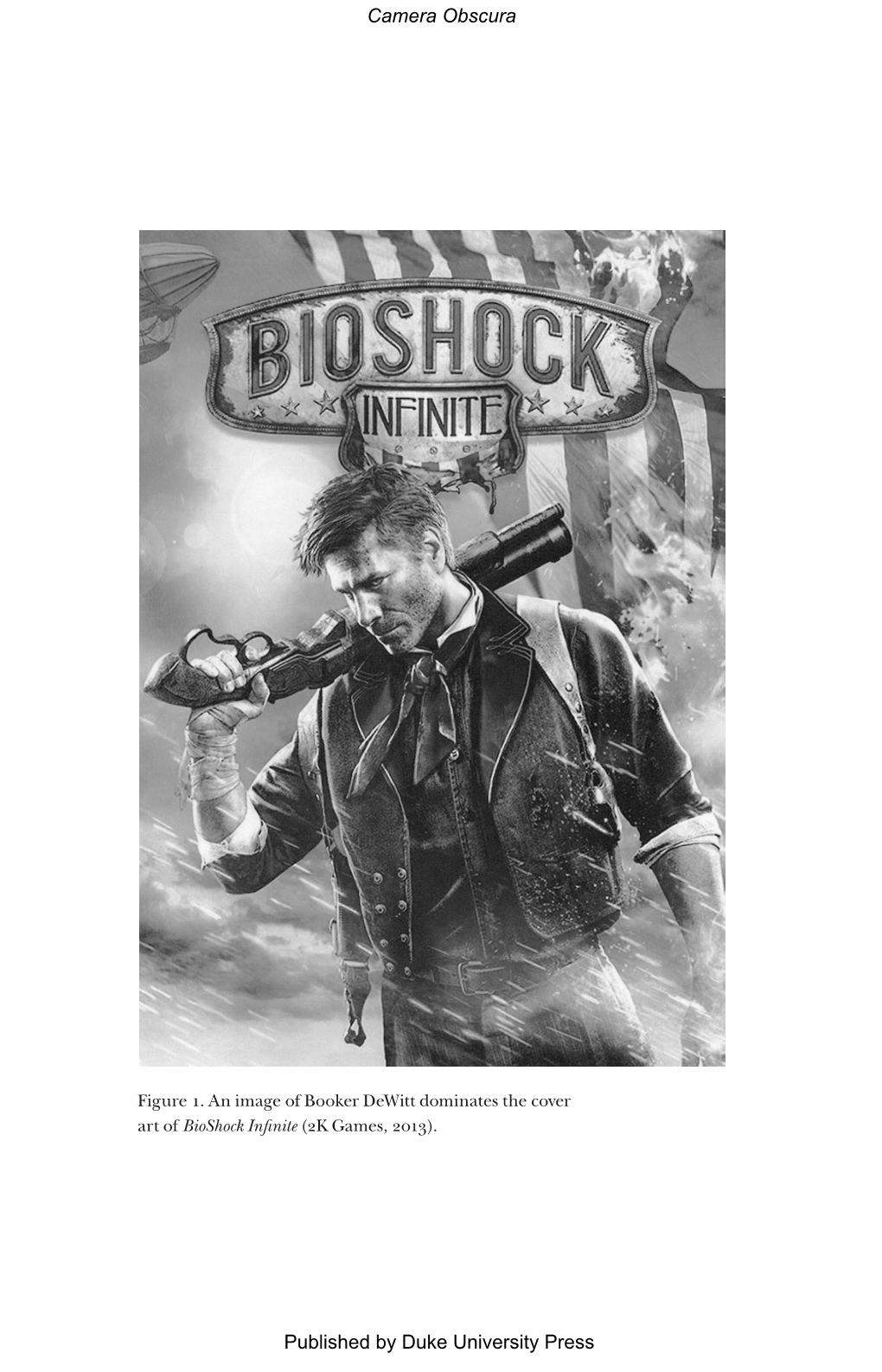

Everyman, All at Once Formatted 4.10.18

Ben Phelan Brigham Young University, United States Everyman, All at Once Baptism and the Liberal Subject in BioShock Infinite Even as liberalism has penetrated nearly every nation on earth, its vision of human liberty seems increasingly to be a taunt rather than a promise. —Patrick J. Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed Abstract The 2013 video game BioShock Infinite stages baptism as a way to place the player within a liminal space where he or she is ostensibly a free subject, able to choose from an array of political options, but who will inevitably choose liberalism. In order to get the player to the point where they make—or rather confirm—their choice, the game must also force the player to arrive there. This conundrum mirrors the paradox of liberalism, following theorists like Patrick J. Deneen: that we supposedly choose among a realm of infinite possibly and yet those possibilities are forced upon us. This paradox is also the mode within which BioShock Infinite operates. The game uses self-referential and metatextual techniques to call attention to its gameness, and yet, it still asks the player to accept its liberal ideology. Althusser argues that the role of “Ideological State Apparatuses” (or ISAs) is to convince us that we are subjects who freely choose the dominant ideology, as opposed to any other system. ISAs do this through confirming us as subjects through rituals of ideological recognition enacted through, among other things, theatre, film, and video games. BioShock Infinite places the player in a position where they confirm that they are, indeed, a liberal subject, and then asks that liberal subject to choose the very order from which their (mis)recognition occurs. -

Bioshock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two Available for Download Starting Today

BioShock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two Available for Download Starting Today March 25, 2014 8:00 AM ET Irrational Games delivers its final episode and concludes the story of BioShock Infinite and Burial at Sea NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Mar. 25, 2014-- 2K and Irrational Games announced today that BioShock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two is downloadable* in all available territories** on the PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft and Windows PC starting today. BioShock Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two, developed from the ground up by Irrational Games, is the final content pack for the award-winning BioShock Infinite, and features Elizabeth in a film noir-style story that provides players with a different perspective on the BioShock universe. “I think the work the team did on this final chapter speaks for itself,” said Ken Levine, creative director of Irrational Games. “We built something that is larger in scope and length, and at the same time put the player in Elizabeth’s shoes. This required overhauling the experience to make the player see the world and approach problems as Elizabeth would: leveraging stealth, mechanical insight, new weapons and tactics. The inclusion of a separate 1998 Mode demands the player complete the experience without any lethal action. BioShock fans are going to plotz.” *BioShock Infinite is not included in this add-on content, but is required to play all of the included content. **BioShock Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two will be available in Japan later this year. About BioShock Infinite From the creators of the highest-rated first-person shooter of all time***, BioShock, BioShock Infinite puts players in the shoes of U.S. -

Music, Time and Technology in Bioshock Infinite 52 the Player May Get a Feeling That This Is Something She Does Frequently

The Music of Tomorrow, Yesterday! Music, Time and Technology in BioShock Infinite ANDRA IVĂNESCU, Anglia Ruskin University ABSTRACT Filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino have taken full advantage of the disconcerting effect that pop music can have on an audience. Recently, video games have followed their example, with franchises such as Grand Theft Auto, Fallout and BioShock using appropriated music as an almost integral part of their stories and player experiences. BioShock Infinite takes it one step further, weaving popular music of the past and pop music of the present into a compelling tale of time travel, multiverses, and free will. The third installment in the BioShock series has as its setting the floating city of Columbia. Decidedly steampunk, this vision of 1912 makes considerable use of popular music of the past alongside a small number of anachronistic covers of more modern pop music (largely from the 1980s) at crucial moments in the narrative. Music becomes an integral part of Columbia but also an integral part of the player experience. Although the soundscape matches the rest of the environment, the anachronistic covers seem to be directed at the player, the only one who would recognise them as out of place. The player is the time traveller here, even more so than the character they are playing, making BioShock Infinite one of the most literal representations of time travel and the tourist experience which video games can represent. KEYWORDS Video game music, film music, intertextuality, time travel. Introduction For every choice there is an echo. With each act we change the world […] If the world were reborn in your image, Would it be paradise or perdition? (BioShock 2 launch trailer, 2010) Elizabeth hugs a postcard of the Eiffel Tower. -

Interactive Emotions: Empathy in the Bioshock Series* *Spoiler Warning: This Paper Contains Spoilers for the Bioshock Series of Video Games

Archived article from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s Journal of Undergraduate Research, retrieved from UNC Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ University of North Carolina at Asheville Journal of Undergraduate Research Asheville, North Carolina December 2013 Interactive Emotions: Empathy in the Bioshock Series* *Spoiler Warning: This paper contains spoilers for the Bioshock series of video games. Zac Hegwood Literature: Concentration in Creative Writing The University of North Carolina at Asheville One University Heights Asheville, NC 28804 USA Faculty Advisor: Dr. Amanda Wray Abstract Video games are a multi-billion dollar industry, embraced by a large majority of U.S. households. People of all ages and from all backgrounds participate in the stories and experiences offered by these games. Unfortunately, most of the research done on videogames considers them only from a technical aspect: how they assist in cognitive abilities (see Oei and Patterson, 2013) or how they make us violent or cooperative (see Saleem, Anderson, and Gentile, 2012). Both of these research foci underestimate video games as an interactive form of storytelling. My undergraduate research project attempts to address this gap by studying video games as a medium of literature that creates an emotive experience for the user through interactive storytelling. Building upon interviews conducted at the Escapist Expo in Durham, NC, and current game theory scholarship, this paper deconstructs the use of emotion within the critically-acclaimed 2013 video game “Bioshock: Infinite,” and the entire Bioshock series. In particular, I analyze how the games’ interactive/empathetic components force players to question our conceptualizations of the culturally relevant themes of religion, race, and social class. -

Jordan Erica Webber Jordan Erica Webber Is a Freelancer Who Writes and Talks About Games for the Observer, PC Gamer, Gamestm, Family Gamer TV, IGN, and More

preview v redefine By the time this issue goes to ‘press’, I’ll be putting the finishing touches on a presentation for the Critical Proximity conference in San Francisco. This will be a prerecorded video - somewhat ironic given the word ‘prox- imity’ in the title - about how magazines can exist in the age of instant, unlimited, free information. Now we’re into our second year, we have demonstrated that we can continue to exist. But by producing a ten- minute talk that justifies your existence, it does make you think: are we heading in the right direction? Are we meeting our own expectations? Our second year is about sustainability: taking a production and process that we made up as we went along and refining it into something that can stand the test of time. There will always be ups and downs - life has a habit of getting in the way of art, as well as influencing it - but those setbacks give us the resolve to fight back even stronger. This issue’s theme is ‘Power’, and that’s all the direction we have given our contributors. We want to create a blank canvas for our writers - we’ve even got two comics from Elizabeth Simins, who also designed our front cover. I’d be lying if I said I knew what the future holds for Five out of Ten, but I sure am excited about it. I guess that’s one way to define power. Alan Williamson Alan is the Editor of Five out of Ten, occasional contributor to the New Statesman, Eurogamer (that’s a new one!) and Critical Distance. -

Bioshock: the Collection Available Now on PS4™ and Xbox One

BioShock: The Collection Available Now on PS4™ and Xbox One September 13, 2016 8:00 AM ET Revisit the worlds of Rapture and Columbia, fully remastered for modern consoles Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #BioShock NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 13, 2016-- 2K announced today that BioShock®: The Collection is available now in North America for the PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system, and Xbox One, containing all three installments of the award-winning BioShock franchise fully remastered for modern consoles. Originally developed by Irrational Games and 2K Marin, and revitalized in full 1080p HD and up to 60 frames-per-second by Blind Squirrel Games, BioShock: The Collection brings all three games and all single-player add-on content from one of the highest-rated franchises* of the last console generation to new audiences at an incredible value of $59.99. BioShock: The Collection will be available for the PS4™ system and Xbox One in Australia on September 15, 2016, and internationally on September 16, 2016, and will be released globally on Windows PC via Steam on September 15th, 2016 at 3:00 p.m. PT. PC owners of BioShock, BioShock 2, and/or Minerva’s Den will be able to access the remastered versions of these titles as a free upgrade. For more details on the upgrade process, please visit the official 2K blog. “We’re immensely proud of the BioShock series, and we’ve taken great care in bringing these beloved games to the current generation of consoles,” said Christoph Hartmann, President of 2K. “Whether you’ve experienced these critically acclaimed classics before or are new to the series, there’s never been a better time to play and immerse yourself in the rich worlds of Rapture and Columbia.” BioShock: The Collection brings together the epic and immersive stories set in the BioShock universe in one incredible package with 1080p resolution and up to 60 frames-per-second, along with new and improved textures and art assets created by Blind Squirrel Games. -

Pdf, 204.06 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Music Transition “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:19 Jesse Host It’s Bullseye. I’m Jesse Thorn. This next interview is about video Thorn games. And even if that’s not the kind of thing you’re into—maybe you don’t know what Fortnite is or the last console you owned was a Sega Genesis, but still, hear me out. You’re gonna wanna keep listening. For the better part of a decade, the video game industry has made more in revenue than Hollywood. Year after year. It’s not even close anymore. The two industries have a fair amount in common. Both movies and video games take enormous amounts of work to produce—work that spans dozens of disciplines, sometimes employing thousands of people on a single project. There are big studios, small studios, indie projects, multibillion dollar franchises. But the video game industry—at least compared to film and TV—is relatively new. It’s changing constantly. Sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. And the folks who make these games, most of them don’t have the same protections movie crews find in, say, a union or guild. Jason Schreier has made a career reporting on exactly that. -

Characterization, Purpose, and Action: Creating Strong Characters in Video Games

Characterization, Purpose, and Action: Creating Strong Characters in Video Games Jeremy Bernstein @fajitas Freelance Writer/Designer Hi. I am a silent protagonist. I have no voice of my own. This helps you empathize with me. As I have no characteristics of my own… …you can imbue me… …with any characteristic you want. I’m just like you. Isn’t it great? We’re like BFFs! ? Silent Cinematic Open Half-Life Uncharted Walking Dead Portal/Portal 2 Gears of War The Room God of War Bioshock Bioshock Infinite Dead Space Dead Space 2 Linear Zelda GTA Fallout Myst Batman: Arkham Fable Elder Scrolls Dragon Age Sandbox ? Silent Cinematic Open Half-Life Uncharted Walking Dead Portal/Portal 2 Gears of War The Room God of War Bioshock Bioshock Infinite Dead Space Dead Space 2 Linear Zelda GTA Fallout Myst Batman: Arkham Fable Elder Scrolls Dragon Age Sandbox Yes* * WARNING: Theory may be neither grand nor unifying I THESE GAMES Why character? Deborah Hendersen, User Researcher Why character? Story:Character: A Definition A Definition The People In the Story Story in games? Must we? Story: A Definition Someone who wants something badly and is havingOBJECTIVE a hard time getting it. GAMEPLAYOBSTACLE SOMEONEPROTAGONIST OBSTACLE OBSTACLE OBSTACLE OBJECTIVEWANT Story:Character: A Definition A Definition PROTAGONIST Someone who wants something badly and is having a hard time getting it. Character: A Definition PROTAGONIST Someone who wants something badly Character: A Definition PROTAGONIST Someone who WANTS wants something badly Character: A Definition PROTAGONIST -

The Sacred and the Digital. Critical Depictions of Religions in Digital Games

religions Editorial The Sacred and the Digital. Critical Depictions of Religions in Digital Games Frank G. Bosman Department of Systematic Theology and Philosophy, Tilburg University, 5037 AB Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] Received: 17 January 2019; Accepted: 21 February 2019; Published: 22 February 2019 Abstract: In this editorial, guest editor Frank Bosman introduces the theme of the special issue on critical depictions of religion in video games. He does so by giving a tentative oversight of the academic field of religion and video game research up until present day, and by presenting different ways in which game developers critically approach (institutionalized, fictional and non-fictional) religions in-game, of which many are discussed by individual authors later in the special issue. In this editorial, Bosman will also introduce all articles of the special issue at hand. Keywords: game studies; religion studies; games and religion studies; religion criticism 1. Introduction Video game studies are a relative young but flourishing academic discipline. But within game studies, however, the perspective of religion and spirituality is rather neglected, both by game scholars and religion scholars. Although some fine studies have appeared, like Halos & Avatars (Detweiler 2010), Godwired. Religion, ritual, and virtual reality (Wagner 2012), eGods. Faith versus fantasy in computer gaming (Bainbridge 2013), Of Games and God (Schut 2013), Playing with Religion in digital games (Campbell and Grieve 2014), Methods for Studying Video Games and Religion (Sisler et al. 2018), and Gaming and the Divine (Bosman 2019), still little attention has been given to the depiction of religion, both institutionalized and privatized, both fantasy and non-fictional, deployed by game developers for their games’ stories, aesthetics, and lore. -

The Purposes and Meanings of Video Game Bathrooms

The Purposes and Meanings of Video Game Bathrooms David Antognoli Joshua Fisher Interactive Arts and Media Department Interactive Arts and Media Department Columbia College Chicago Columbia College Chicago Chicago, US Chicago, US [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— Through an archaeogaming framing and an object- II. PRIVACY AND THE HISTORICAL REPRESENTATION OF THE inventory method, the purposes and meanings of video game BATHROOM bathrooms are put forward with a framework. The framework assesses each video game bathroom based on its immersive An analysis of video game bathrooms to ascertain their qualities, ludic affordances, and ideological commentary. By purposes and meanings intersects with the concept of privacy. analyzing games and establishing the framework, this article The bathroom or toilet has been historically viewed, in Western addresses how designers employ these affordances to use culture, as a private and solitary affair [3], [4]. As urban studies bathrooms as representative spaces. While bathrooms in video scholars Rob Kitchin and Robin Law observe, “The dominant games contribute to a sense of place through environmental Western norms of proper toilet behaviour for adults include storytelling, they also represent situated perspectives on privacy, discreetly dealing with your body’s needs, away from the gaze cleanliness, dirt, gender, and other ideological concepts. This of others, in demarcated settings with some spatial separation article places video game bathrooms in a larger history of from other activity spaces, using facilities which meet public bathroom representations in media. However, unlike other media, health standards on the disposal of human waste and control of video games enable players to view themselves in different bodies dirt” [5]. -

Roles of Female Video Game Characters and Their Impact on Gender Representation

Roles of female video game characters and their impact on gender representation. Author: Paulina Ewa Rajkowska Thesis Supervisor: Else Nygren Master's Thesis Submitted to the Department of Informatics and Media Uppsala University, May 2014 For obtaining the Master's Degree of Social Science In the field of Media and Communication Studies Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background Information ................................................................................................ 5 What are video games? .................................................................................................. 5 Important terms .............................................................................................................. 7 Evolution of games ......................................................................................................... 8 3. Literature review: ......................................................................................................... 12 Media Effects: .............................................................................................................. 12 The concept of Gender ................................................................................................. 13 Gender in video games ................................................................................................