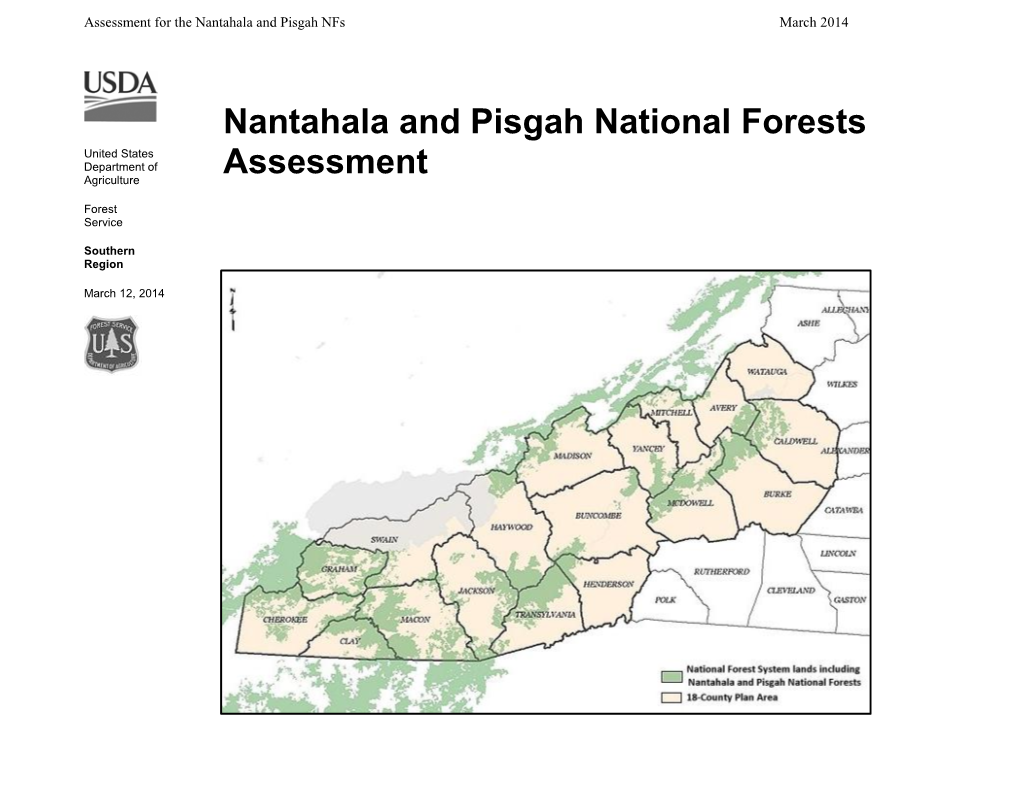

Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North Carolina Arboretum Reopens Bonsai Exhibit for the 2018 Season on World Bonsai Day, Saturday, May 12

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Whitney Smith, Marketing & PR Manager [email protected] (828) 665-2492 x204 The North Carolina Arboretum Reopens Bonsai Exhibit for the 2018 Season on World Bonsai Day, Saturday, May 12 ASHEVILLE, N.C. (May 4, 2018) – The North Carolina Arboretum, a 434-acre public garden located just south of Asheville, will celebrate the mighty power of tiny trees at its World Bonsai Day event on Saturday, May 12, 2018, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. inside its Bonsai Exhibition Garden. This popular annual celebration marks the reopening of the Arboretum’s full bonsai display for the season and includes educational programming related to bonsai trees and maintenance. As part of the event, from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., representatives from the local Blue Ridge Bonsai Society will be on site to present informal programs related to basic bonsai information, including how to get started and how to maintain a bonsai, as well as discussing what design features are desirable in a good bonsai. These programs are free to the public and club members will also be available to answer questions. “We are excited and thankful to have members from the Blue Ridge Bonsai Society at the Arboretum to share their knowledge with our visitors and members, and help us celebrate the reopening of our bonsai display,” said Arthur Joura, award-winning bonsai curator at The North Carolina Arboretum. World Bonsai Day is an international event dedicated to furthering bonsai awareness and appreciation worldwide. Initiated by the World Bonsai Friendship Federation (WBFF) in honor of Mr. -

Design of Bioreactors for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tissue Engineering

Design of Bioreactors for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tissue Engineering Pankaj Godara A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Engineering Graduate School of Biomedical Engineering 2010 Originality Statement ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substan- tial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowl- edgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ...................................................... Date ...................................................... Copyright Statement ‘I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University li- braries in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the abstract of my thesis in Dissertations Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Word Catalogue.Docx

H.J. Pugh & Co. HAZLE MEADOWS AUCTION CENTRE, LEDBURY, HEREFORDSHIRE HR8 2LP ENGINEERING MACHINERY, LATHES, MILLS, SAWS, DRILLS AND COLLECTABLE TOOLS, SEASONED AND GREEN SAWN TIMBER SATURDAY 2nd JANUARY 9:30AM Viewing 29th 30th & 31st Dec 9am - 1pm and 8am onward morning of sale 10% buyers premium + VAT 2 Rings RING 1 1-450 (sawn timber, workshop tools, machinery and lathes) 9:30am RING 2 501-760 (specialist woodworking tools and engineering tools) 10am Caterer in attendance LIVE AND ONLINE VIA www.easyliveauction.com Hazle Meadows Auction Centre, Ledbury, Herefordshire, HR8 2AQ Tel: (01531) 631122. Fax: (01531) 631818. Mobile: (07836) 380730 Website: www.hjpugh.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. All prospective purchasers to register to bid and give in their name, address and telephone number, in default of which the lot or lots purchased may be immediately put up again and re-sold 2. The highest bidder to be the buyer. If any dispute arises regarding any bidding the Lot, at the sole discretion of the auctioneers, to be put up and sold again. 3. The bidding to be regulated by the auctioneer. 4. In the case of Lots upon which there is a reserve, the auctioneer shall have the right to bid on behalf of the Vendor. 5. No Lots to be transferable and all accounts to be settled at the close of the sale. 6. The lots to be taken away whether genuine and authentic or not, with all faults and errors of every description and to be at the risk of the purchaser immediately after the fall of the hammer but must be paid for in full before the property in the goods passes to the buyer. -

Production of Yttrium Aluminum Silicate Microspheres by Gelation of an Aqueous Solution Containing Yttrium and Aluminum Ions in Silicone Oil

Volume 12, No 2 International Journal of Radiation Research, April 2014 Production of yttrium aluminum silicate microspheres by gelation of an aqueous solution containing yttrium and aluminum ions in silicone oil M.R. Ghahramani*, A.A. Garibov, T.N. Agayev Institute of Radiation Problems, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Baku, Azerbaijan ABSTRACT Background: Radioacve yrium glass microspheres are used for liver cancer treatment. These yrium aluminum silicate microspheres are synthesized from yrium, aluminum and silicone oxides by melng. There are two known processes used to transform irregular shaped glass parcles into ► Original article microspheres, these ‘spheroidizaon by flame’ and ‘spheroidizaon by gravitaonal fall in a tubular furnace’. Materials and Methods: Yrium aluminum silicate microspheres with the approximate size of 20‐50 µm were obtained when an aqueous soluon of YCl3 and AlCl3 was added to tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and pumped in to silicone oil and srred constantly the * Corresponding author: temperature of 80˚C. The resulng spherical shapes were then invesgated Dr. M.R. Ghahramani, for crystallizaon, chemical bonds, composion and distribuon of elements Fax: +99 41 25398318 by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X‐ray diffracon (XRD), Fourier E‐mail: transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), carbon/sulfur analysis, X‐ray [email protected] photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and SEM/EDS analysis. Results: The parcles produced by the above‐menoned method were regular and nearly Received: July 2013 spherical in shape. The results of topographical analysis of a cross‐secon Accepted: Oct. 2013 showed that form of the microspheres had formed a ‘boiled egg’ structure. This method has an advantage over other methods in that the process does Int. -

B-Hikes (3 to 6 Miles)

B-HIKES (3 TO 6 MILES) = Trails maintained by MHHC ## = Designated Wilderness Area B3 Appletree Trail Loop . This is a new 5 mile hike for the Club. Moderate climbing, Start out of the campground on the Appletree Trail for 1.6 miles, then turn onto Diamond Valley Trail for 1.1 miles, the turn onto Junaluska Trail for 2 miles back to Appletree Trail and .2 miles back to trailhead. Several moderate climbs, uneven trail. Pretty cove. Meet at Andrews Rest Area, Hwy 74/19/129 B2 ## Arkaquah Trail from Brasstown Bald parking lot. An easy in and out hike of about 3 miles. Spectacular views. Some rough footing. Meet at Jacks Gap at base of Brasstown Bald on Hwy. 180. B3 ## Arkequah Trail from Brasstown Bald parking lot down. This is a moderate hike of about 5.5 miles, mostly downhill. Spectacular views. See the petro glyphs at the end. Some rough footing. Shuttle Meet at Blairsville Park and Ride B2 Bartram Trail from Warwoman Dell (3 miles east of Clayton) to the viewing platform at Martin Creek Falls. This scenic (4 mile) round trip also passes by Becky Creek Falls. Meet at Macedonia Baptist Church parking lot east of Hiawassee. B3## Bear Hair Trail in Vogel State Park. Loop hike of about 4 miles with some moderate to steep climbs. Bring hiking sticks and State Park pass or $5. Meet at Choestoe Baptist Church parking lot on Hwy 180. B1 Benton Falls, Red Leaf, Arbutus, Azalea, Clear Creek Trails in the Chilhowee Recreation Area in east Tennessee. 4.8 mile easy trail. -

Moorhead Ph 1 Final Report

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Ecological Assessment of a Wetlands Mitigation Bank August 2001 (Phase I: Baseline Ecological Conditions and Initial Restoration Efforts) 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Kevin K. Moorhead, Irene M. Rossell, C. Reed Rossell, Jr., and James W. Petranka 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Departments of Environmental Studies and Biology University of North Carolina at Asheville Asheville, NC 28804 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Research and Special Programs Administration May 1, 1994 – September 30, 2001 400 7th Street, SW Washington, DC 20590-0001 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation and the North Carolina Department of Transportation, through the Center for Transportation and the Environment, NC State University. 16. Abstract The Tulula Wetlands Mitigation Bank, the first wetlands mitigation bank in the Blue Ridge Province of North Carolina, was created to compensate for losses resulting from highway projects in western North Carolina. The overall objective for the Tulula Wetlands Mitigation Bank has been to restore the functional and structural characteristics of the wetlands. Specific ecological restoration objectives of this Phase I study included: 1) reestablishing site hydrology by realigning the stream channel and filling drainage ditches; 2) recontouring the floodplain by removing spoil that resulted from creation of the golf ponds and dredging of the creek; 3) improving breeding habitat for amphibians by constructing vernal ponds; and 4) reestablishing floodplain and fen plant communities. -

City Bio Asheville, North Carolina Is Located in Western North Carolina; It Is Located in Buncombe County

City Bio Asheville, North Carolina is located in Western North Carolina; it is located in Buncombe County. It is known as the largest city in Western North Carolina and is the 11th largest city in North Carolina overall. The city of Asheville is known for its art and architecture. Fun Fact The National Climate Data Center (NCDC) is located in Ashville and is known as the world’s largest active archive of weather data. You can take a tour of the NCDC, which is located at 151 Patton Avenue. Places to See Biltmore Estates: is the largest privately owned house in the United States, owned by the Vanderbilt family. From the complex, to the gardens, to the winery, to the shopping and outdoor activities there is plenty to see at the Estate and is said to take up a long portion of your day, so plan accordingly. Located at 1 Lodge Street. Basilica of Saint Lawrence: is a Roman Catholic Church, a minor basilica thanks to the upgraded status from Pope John Paul II, it is on the National Register of Historic Places. Located at 97 Haywood Street. North Carolina Arboretum: is a great place to walk, bike and educate, the location is full of gardens, national parks with great views and educational sites. There are activities for both younger and older children. Located at 100 Frederick Law Olmsted Way. Asheville Zipline Canopy Adventures: is a 124 acre zipline course that takes you into 150 year old trees that overlook historic downtown and the Blue Ridge Mountains. The experience takes around 2-3 hours long so plan accordingly. -

The Nikwasi Indian Mound

The Nikwasi Indian Mound The Nikwasi Indian Mound is the last remnant of a Cherokee town of the same name which once stood here on the banks of the Little Tennessee River. The Cherokee Nation towns were divided into Lower, Middle, and Over the Hill Towns. The Middle Towns, of which Nikwasi was one, were found every few miles along the Little Tennessee and its tributaries from its headwaters to the Smokies. While the mound was probably built during the earlier Mississippian Culture, it was the spiritual center of the area. A Council House, or Town House, used for councils, religious ceremonies, and general meetings, was located on top the mound, and the ever-burning sacred fire, which the Cherokee had kept burning since the beginning of their culture, was located there. Thus the mound was a most revered site. The town of Nikwasi was a "white", or peace, town. It was believed that the Nunne'hi, the spirit people, lived under this mound. When James Mooney was studying the legends of the Cherokee for the Smithsonian in 1887 - 1890, he was told the legend of these Spirit Defenders of Nikwasi by an old medicine man name Swimmer. Today it stands as a stately and silent reminder of a time, a culture, and a people of a bygone era. The mound has never been excavated for any reason, agricultural, archeological, or commercial. It stands at near its original height. One cannot truly experience the mound by merely driving by. One must stand at the base to appreciate the size and grace of Nikwasi, and try to envision a time from the past when the mound was surrounded not by busy 21st century traffic and businesses, but by fields, orchards, and a people who lived in complete harmony with the land and the river. -

Pisgah Forest, NC, 28769

OFFERING MEMORANDUM 3578 HENDERSONVILLE HWY | PISGAH FOREST, NC REPRESENTATIVE PHOTO ™ 3578 HENDERSONVILLE HWY | PISGAH FOREST, NC 3 INVESTMENT SUMMARY EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY: WESLEY CONNOLLY Associate VIce President 4 D: +1 (949) 432-4512 FINANCIAL SUMMARY M: +1 (707) 477-7185 [email protected] License No. 01962332 (CA) 6 KYLE MATTHEWS Broker of Record TENANT PROFILE License No. C27092 (NC) 7 AREA OVERVIEW 2 Dollar General INVESTMENT SUMMARY 3578 Hendersonville Hwy ADDRESS Pisgah Forest, NC 28769 $1,360,780 6.15% $83,688 ±9,100 SF 2017 LIST PRICE CAP RATE ANNUAL RENT GLA YEAR BUILT PRICE $1,360,780 CAP RATE 6.15% NOI $83,688 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS GLA ±9,100 SF Corporate Guaranteed Essential Retailer LOT SIZE ±6.72 AC • Newer construction building with long term absolute NNN Lease; No YEAR BUILT 2017 Landlord Responsibilities • Dollar General has investment grade rated corporate guarantee • Dollar General has been identified as an essential retailer and has maintained business operations throughout the Covid-19 Pandemic DEMOGRAPHICS Prototypical Dollar General Market 3-MILE 5-MILE 10-MILE • Lack of Major competition in immediate vicinity POPULATION 5,225 17,083 61,536 • 33 miles from Asheville, NC HOUSEHOLDS 2,453 7,440 27,369 • 10 Mile Population in excess of 61,615 HH INCOME $68,333 $73,778 $79,155 • Minutes to John Rock, Looking Glass Rock, and Coontree Mountain Dollar General 3 FINANCIAL SUMMARY ANNUALIZED OPERATING DATA LEASE COMMENCE MONTHLY RENT ANNUAL RENT CAP RATE Lease Type NNN Type of Ownership Fee Simple Current -

March 1999 No

The Area meet wrap-up ► 4 - - Spiral screwdrivers ► 14 r1stm1 Old signboards ► 16 Auxiliary news ► 22 A Publication of the Mid-West Tool Collector's Association M-WTCA.ORG Wooden patent model of a J. Siegley plane. Owned by Ron Cushman. March 1999 No. 94 Chaff N. 94 March, 1999 Copyright 1999 by Mid-West Tool Collectors Assodation, Inc. All rights reserved. From the President Editor Mary Lou Stover S76Wl9954 Prospect Dr. I have just Muskego, WI 53150 a new feature in this issue. Check out Associate Editor Roger K. Smith returned from a the list and ask yourself if you might be Contributing Editor Thomas Lamond PAST meeting in San of help. I am sure that most of those Advertising Manager Paul Gorham Diego where I was making a study do not actually own THE GRISTMILL is the official publication of the Mid-West Tool Collectors Association, Inc. Published 4uar1erly in March. June, welcomed by PAST each piece they include in the study. September and December. "Chief' Laura Pitney The purpose of the association is lo promote the preservation, You might have a tool the researchers study and understanding of ancient tools, implements and devices and other members. need to know about. If you think you of farm, home, industry and shop of lhc pioneers; also, lo study the crafts in which these objects were used and the craftsmen who The weather was can help in an area, please contact one of used them; and to share knowledge and understanding with others, especially where ii may benefit rcsloralion, museums and like quite different than the authors. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide North Carolina Byway Highway # "Waterfall Byway"

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide North Carolina Byway Highway # "Waterfall Byway" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Start of Waterfall Byway Byway starts at the juction of United States Highway #64 with State Highway #215 at Rosman, North Carolina. This byway passes through lands full of scenic wonder and historical significance. Bridal Veil Falls has a spectacular 120-foot cascade into the Cullasaja River. Nearby Dry Falls derives its name from the fact that visitors can walk behind the falls without getting wet. Byway towns such as Gneiss and Murphy are important landmarks about North Carolina's Native American history. 1.1 Old Toxaway Road / State Old Toxaway Road / State Route #1139, Frozen Lake, Fouth Falls, Route #1139 Upper Whitewwater Falls, Lake Jocassee, The Wilds Christian Association, a Protestant Christian organization, located here in North Carolina 2.6 Silverstein Road Silverstain Road / State Route #1309, Quebec, North Carolina, 3.7 Flat Creek Valley Road Flat Creek Valley Road / State Route #1147, 3.8 Oak Grove Church Road 5.3 Flat Creek Valley Road Flat Creek Valley Road / State Route #1147, Toxaway River, 5.4 Indian Creek Trail Road Indian Creek Trail Road, Falls Country Club, 6.8 Lake Toxaway, North Junction State Highway #281, Lake Toxaway, a community in Carolina Transylvania County, North Carolina, Tanasee Creek Reservoir, Wolf Mountain, North Carolina, Wolf Creek Reservoir, 7.3 Toxaway Fall Drive Toxaway Fall Drive, Lake Toxaway Spillway, Toxaway Lake, the largest man-made , privately held Lake in North Carolina. This is fed by natureal streams and flows out to make Toxaway Falls and on to Toxaway River. -

July 2013 Wannagofast Is Back! Wanna GO Last September, Thousands Came to Heaven’S Landing FAST for a One Day Event of Epic Magnitude!

Like no Place on Earth July 2013 wannaGOFAST is Back! Wanna GO Last September, thousands came to Heaven’s Landing FAST for a one day event of epic magnitude! Heaven's Landing is pleased to announce the return of Oshkosh wannaGOFAST 1/2 Mile Shootout this fall! On September 14 and 15, enjoy TWO days of outstanding up-close action on the beautiful 5,069 foot Heaven’s Landing runway. Two days Baby Greer filled with camaraderie, speed, industry vendors and experts, and every car imaginable. Join us for a weekend adventure Father’s Day with your friends and family; or maybe, you have plans to be behind the wheel, on the track, living your dream! Air McIntosh We’ve learned that registration for drivers has JUST closed! However, it is not too late to plan your trip and have a great time on the sidelines! Operation 300 WannaGOFAST brings all types of participants and spectators together. On the Heaven’s Landing airfield, you will find car enthusiasts and experienced drivers. Some will come with their Lamborghini and others with a souped-up Pinto! (There are always surprises!) This year, 125 cars Gorgeous per day will compete, doubling the action. Hopefully, if you wish to be on the runway, you have Gorges already secured your seat behind the wheel and are gearing up to race down the precision timed 1/2 mile field; if not, the good news is there is a waitlist, so get on it FAST. Streets Over the past year, the wannaGOFAST events have grown both in scope and in word of mouth at each venue.