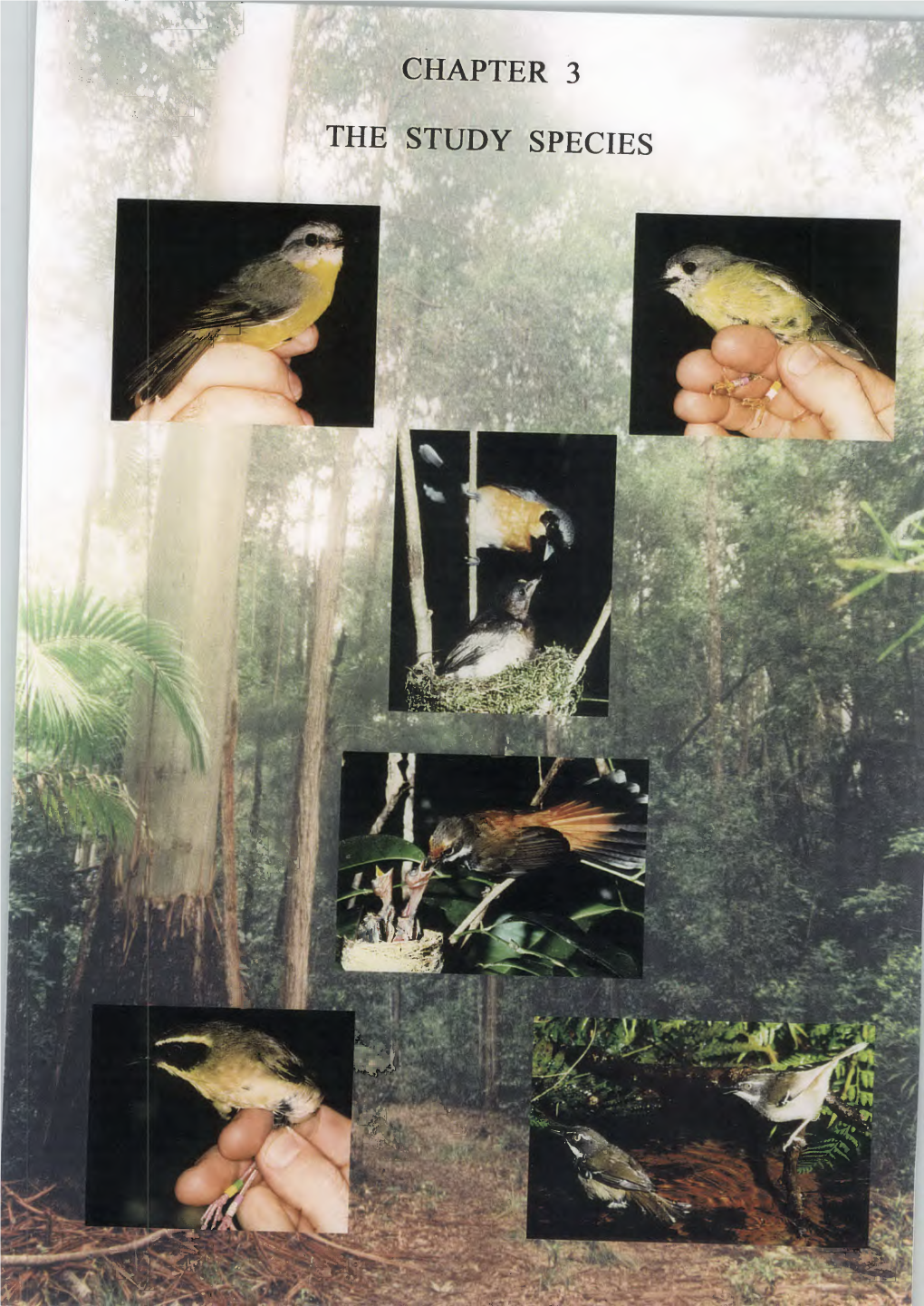

Chapter 3 the Study Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solomon Islands

THE SOLOMON ISLANDS 14 SEPTEMBER – 7 OCTOBER 2007 TOUR REPORT LEADER: MARK VAN BEIRS Rain, mud, sweat, steep mountains, shy, skulky birds, shaky logistics and an airline with a dubious reputation, that is what the Solomon Islands tour is all about, but these forgotten islands in the southwest Pacific also hold some very rarely observed birds that very few birders will ever have the privilege to add to their lifelist. Birdquest’s fourth tour to the Solomons went without a hiccup. Solomon Airlines did a great job and never let us down, it rained regularly and we cursed quite a bit on the steep mountain trails, but the birds were out of this world. We birded the islands of Guadalcanal, Rennell, Gizo and Malaita by road, cruised into Ranongga and Vella Lavella by boat, and trekked up into the mountains of Kolombangara, Makira and Santa Isabel. The bird of the tour was the incredible and truly bizarre Solomon Islands Frogmouth that posed so very, very well for us. The fantastic series of endemics ranged from Solomon Sea Eagles, through the many pigeons and doves - including scope views of the very rare Yellow-legged Pigeon and the bizarre Crested Cuckoo- Dove - and parrots, from cockatoos to pygmy parrots, to a biogeographer’s dream array of myzomelas, monarchs and white-eyes. A total of 146 species were seen (and another 5 heard) and included most of the available endemics, but we also enjoyed a close insight into the lifestyle and culture of this traditional Pacific country, and into the complex geography of the beautiful forests and islet-studded reefs. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

The Avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, Including Evidence for Long-Term Population Dynamics in Undisturbed Tropical Forest

Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman 30 Bull. B.O.C. 2014 134(1) The avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, including evidence for long-term population dynamics in undisturbed tropical forest Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman Received 27 July 2013 Summary.—We conducted ornithological feld work on Mt. Karimui and in the surrounding lowlands in 2011–12, a site frst surveyed for birds by J. Diamond in 1965. We report range extensions, elevational records and notes on poorly known species observed during our work. We also present a list with elevational distributions for the 271 species recorded in the Karimui region. Finally, we detail possible changes in species abundance and distribution that have occurred between Diamond’s feld work and our own. Most prominently, we suggest that Bicolored Mouse-warbler Crateroscelis nigrorufa might recently have colonised Mt. Karimui’s north-western ridge, a rare example of distributional change in an avian population inhabiting intact tropical forests. The island of New Guinea harbours a diverse, largely endemic avifauna (Beehler et al. 1986). However, ornithological studies are hampered by difculties of access, safety and cost. Consequently, many of its endemic birds remain poorly known, and feld workers continue to describe new taxa (Prat 2000, Beehler et al. 2007), report large range extensions (Freeman et al. 2013) and elucidate natural history (Dumbacher et al. 1992). Of necessity, avifaunal studies are usually based on short-term feld work. As a result, population dynamics are poorly known and limited to comparisons of diferent surveys or diferences noticeable over short timescales (Diamond 1971, Mack & Wright 1996). -

Sericornis, Acanthizidae)

GENETIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND PHYLOGENY IN THE AUSTRALO-PAPUAN SCRUBWRENS (SERICORNIS, ACANTHIZIDAE) LESLIE CHRISTIDIS,1'2 RICHARD $CHODDE,l AND PETER R. BAVERSTOCK 3 •Divisionof Wildlifeand Ecology, CSIRO, P.O. Box84, Lyneham,Australian Capital Territory 2605, Australia, 2Departmentof EvolutionaryBiology, Research School of BiologicalSciences, AustralianNational University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia, and 3EvolutionaryBiology Unit, SouthAustralian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia ASS•CRACr.--Theinterrelationships of 13 of the 14 speciescurrently recognized in the Australo-Papuan oscinine scrubwrens, Sericornis,were assessedby protein electrophoresis, screening44 presumptivelo.ci. Consensus among analysesindicated that Sericorniscomprises two primary lineagesof hithertounassociated species: S. beccarii with S.magnirostris, S.nouhuysi and the S. perspicillatusgroup; and S. papuensisand S. keriwith S. spiloderaand the S. frontalis group. Both lineages are shared by Australia and New Guinea. Patternsof latitudinal and altitudinal allopatry and sequencesof introgressiveintergradation are concordantwith these groupings,but many featuresof external morphologyare not. Apparent homologiesin face, wing and tail markings, used formerly as the principal criteria for grouping species,are particularly at variance and are interpreted either as coinherited ancestraltraits or homo- plasies. Distribution patternssuggest that both primary lineageswere first split vicariantly between -

Tropical Birding Tour Report

AUSTRALIA’S TOP END Victoria River to Kakadu 9 – 17 October 2009 Tour Leader: Iain Campbell Having run the Northern Territory trip every year since 2005, and multiple times in some years, I figured it really is about time that I wrote a trip report for this tour. The tour program changed this year as it was just so dry in central Australia, we decided to limit the tour to the Top End where the birding is always spectacular, and skip the Central Australia section where birding is beginning to feel like pulling teeth; so you end up with a shorter but jam-packed tour laden with parrots, pigeons, finches, and honeyeaters. Throw in some amazing scenery, rock art, big crocs, and thriving aboriginal culture you have a fantastic tour. As for the list, we pretty much got everything, as this is the kind of tour where by the nature of the birding, you can leave with very few gaps in the list. 9 October: Around Darwin The Top End trip started around three in the afternoon, and the very first thing we did was shoot out to Fogg Dam. This is a wetlands to behold, as you drive along a causeway with hundreds of Intermediate Egrets, Magpie-Geese, Pied Herons, Green Pygmy-geese, Royal Spoonbills, Rajah Shelducks, and Comb-crested Jacanas all close and very easy to see. While we were watching the waterbirds, we had tens of Whistling Kites and Black Kites circling overhead. When I was a child birder and thought of the Top End, Fogg Dam and it's birds was the image in my mind, so it is always great to see the reaction of others when they see it for the first time. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Scarlet

Corella, 2006, 30(3/4):5945 BREEDINGBIOLOGY AND BEHAVIOUROF THE SCARLETROBIN Petroicamulticolor AND EASTERNYELLOW ROBIN Eopsaltriaaustralis IN REMNANTWOODLAND NEAR ARMIDALE, NEW SOUTH WALES S.J. S.DEBUS Division of Zoology, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351 E-mail: [email protected] Received:I3 January 2006 The breeding biology and behaviour of the Scarlet Robin Petroica multicolor and Eastern Yellow Robin Eopsaltria australis were studied at lmbota Nature Reserve, on the New England Tableland of New South Wales,in 200G-2002by colour-bandingand nest-monitoring.Yellow Robins nested low in shelteredpositions, in plants with small stem diameters(mostly saplings,live trees and shrubs),whereas Scarlet Robins nested high in exposed positions, in plants with large stem diameters (mostly live trees, dead branches or dead trees).Yellow Robin clutch size was two or three eggs (mean 2.2; n = 19). Incubationand nestling periods were 15-17 days and 11-12 days respectively(n = 6) for the Yellow Robin, and 16-18 days (n = 3) and 16 days (n = 1) respectivelyfor the ScarletRobin. Both specieswere multi-brooded,although only YellowRobins successfully raised a second brood. The post-fledging dependence period lasted eight weeks for Yellow Robins, and six weeks for Scarlet Robins. The two robins appear to differ in their susceptibilityto nest predation, with corresponding differences in anti-predator strategies. INTRODUCTION provides empirical data on aspects that may vary geographicallywith seasonalconditions, or with habitator The -

Yarra's Topography Is Gently Undulating, Which Is Characteristic of the Western Basalt Plains

Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgement of country ............................................................................................................................ 3 Message from the Mayor ................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision and goals ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Nature in Yarra .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy and strategy relevant to natural values ................................................................................................. 27 Legislative context ........................................................................................................................................... 27 What does Yarra do to support nature? .......................................................................................................... 28 Opportunities and challenges for nature ......................................................................................................... -

Social Behaviour and Breeding Biology of the Yeliow-Rumped Thornbill

Social Behaviour and Breeding Biology of the Yeliow-Rumped Thornbill Daniel Ebert A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of hilosophy of The Australian National University April 2004 Declaration The research presented in this thesis is my own original work and no part has been submitted for a previous degree. Signed Daniel Ebert April 2004 Dedication In memory of Anjeli Catherine Nathan 18 March 1975 - 3 November 1999 Acknowledgements This thesis was a work in progress, or not, for some years and many people made significant contributions of supervision, assistance or support. My supervisor, Rob Magrath, and Andrew Cockburn and David Green were instrumental in promoting thombill research as a worthwhile pursuit. I thank them for their contributions to the formulation of this project and their interest in my work. Rob Magrath’s particular combination of insight, knowledge and patience was invaluable throughout this study. I am also grateful for the general advice and guidance of Rob Heinsohn and Sarah Legge. This project involved many early morning mist-netting sessions which would have been even more “miss” than “hit” without the enthusiastic assistance of numerous volunteers. David Green, Mike Double, James Nicholls, Sarah Legge, Anjeli Nathan, Janet Gardner, Nie MacGregor, Rob Heinsohn, Rob Magrath, Andrew Cockburn and Peter Marsack all cheerfully participated in the usually unrewarding exercise of netting thombills in the mist and cold. I’m especially grateful to Steve Murphy for his competence and enthusiasm in the field and his impressive ability to find thombill nests after half an hour of “training”. Minisatellite DNA fingerprinting is an error-prone and frustrating procedure usually requiring good fortune as well as good management for success. -

Australia ‐ Part Two 2016 (With Tasmania Extension to Nov 7)

Field Guides Tour Report Australia ‐ Part Two 2016 (with Tasmania extension to Nov 7) Oct 18, 2016 to Nov 2, 2016 Chris Benesh & Cory Gregory For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The sunset over Cumberland Dam near Georgetown was especially vibrant. Photo by guide Cory Gregory. The country of Australia is a vast one, with a wide range of geography, flora, and fauna. This tour, ranging from the Top End over to Queensland (with some participants continuing on to Tasmania), sampled a diverse set of regions and an impressively wide range of birds. Whether it was the colorful selection of honeyeaters, the variety of parrots, the many rainforest specialties, or even the diverse set of world-class mammals, we covered a lot of ground and saw a wealth of birds. We began in the tropical north, in hot and humid Darwin, where Torresian Imperial-Pigeons flew through town, Black Kites soared overhead, and we had our first run-ins with Magpie-Larks. We ventured away from Darwin to bird Fogg Dam, where we enjoyed Large-tailed Nightjar in the predawn hours, majestic Black-necked Storks in the fields nearby, and even a Rainbow Pitta and Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove in the nearby forest! We also visited areas like Darwin River Dam, where some rare Black-tailed Treecreepers put on a show and Northern Rosellas flew around us. We can’t forget additional spots near Darwin, like East Point, Buffalo Creek, and Lee Point, where we gazed out on the mudflats and saw a variety of coast specialists, including Beach Thick-knee and Gull-billed Tern.