Evaluation of an Enterprise Learning Management System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Stephen Peachey

MICHAEL STEPHEN PEACHEY San Mateo, CA www.peachey.com . [email protected] . 415-786-7322 SUMMARY • User experIence advocate, product vIsIonary, executIve producer, and Internet technologIst wIth 15+ years of proven experIence building and leading cross-functional experience desIgn, product management, and engineerIng teams for enterprIse software products and mobIle and web end-user applIcatIons. • SenIor manager wIth P&L responsIbIlIty and a Total QualIty Management focus. • LeadershIp success wIth both start-up and enterprIse-grade teams. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE SUMO LOGIC – ENTERPRISE SAAS, REDWOOD CITY, CA 2015 – PRESENT Business-to-developer cloud log management and analytics software. Vice President, Product Experience 01/2015 - present Built and led global user experience design and development team of 22. Redesigned processes and tools to enable Product and Engineering team success. Led HR and culture development projects. • Recruited and hired top desIgn and UI development talent to focus on cloud-based enterprIse software desIgn problems, successfully onboarding 15 candidates from 16 offers presented In 2015. • Championed a culture of mutual DesIgn and Development accountabilIty, reducIng effort, rework, and cycle times. • StandardIzed desIgn patterns to reduce desIgn rework, delIver a consIstent user experIence, and Increase development velocIty. • Re-engineered UI development processes and re-archItected GUI from Backbone to Angular and MaterIal, signIfIcantly Increasing output per developer and reducing design and dev rework. • Pivoted tech pubs from a homegrown Madcap Flair to Mindtouch, a modern SaaS platform integrated with CX touchpoints In Community, Support and Onboarding, and added capabIlItIes for user tracking and feedback analytics, and SEO optImIzatIon. • Gave voIce to CTO and Product teams though prototypIng of Ideas before desIgn and ImplementatIon, greatly acceleratIng consensus on product dIrectIon before engineerIng kickoff. -

Edutainment Case Study

What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned Carly Shuler The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Fall 2012 1 © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center 2012. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to harness digital media teChnologies to advanCe Children’s learning. The Center supports aCtion researCh, enCourages partnerships to ConneCt Child development experts and educators with interactive media and teChnology leaders, and mobilizes publiC and private investment in promising and proven new media teChnologies for Children. For more information, visit www.joanganzCooneyCenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center has a deep Commitment toward dissemination of useful and timely researCh. Working Closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisors, media sCholars, and praCtitioners, the Center publishes industry, poliCy, and researCh briefs examining key issues in the field of digital media and learning. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniC or meChaniCal, inCluding photoCopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. For permission to reproduCe exCerpts from this report, please ContaCt: Attn: PubliCations Department, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY 10023 p: 212 595 3456 f: 212 875 7308 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Shuler, C. (2012). Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. -

The Role of Information Technology in Fulfilling the Promise of Corporate Social Responsibility

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Brooklyn College 2011 The Role of Information Technology in Fulfilling the Promise of Corporate Social Responsibility David Salb CUNY Kingsborough Community College Hershey H. Friedman CUNY Brooklyn College Linda Weiser Friedman CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bc_pubs/211 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] www.ccsenet.org/cis Computer and Information Science Vol. 4, No. 4; July 2011 The Role of Information Technology in Fulfilling the Promise of Corporate Social Responsibility David Salb, Ph.D. (Corresponding author) Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York 2001 oriental Blvd. Brooklyn, NY 11210 USA Tel: 1-718-368-5925 E-mail: [email protected] Hershey H. Friedman, Ph.D. Department of Economics Brooklyn College of the City University of New York 2900 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210 USA Tel: 1-718-951-2084 E-mail: [email protected] Linda Weiser Friedman, Ph.D. Baruch College Zicklin School of Business and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York 55 Lexington Ave. New York, NY 10010 USA Tel: 1-646-312-3361 E-mail: [email protected] Received: May25, 2011 Accepted: June 14, 2011 doi:10.5539/cis.v4n4p2 The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of PSC-CUNY award #61630-00-39. Abstract Young people today want to work at a meaningful job and make a difference in the world. -

Network Position and Exploratory Knowledge Creation: Evidence from US IT Clusters

HEC MONTRÉAL École affiliée à l’Université de Montréal Network Position and Exploratory Knowledge Creation: Evidence from US IT Clusters YANG GAO Master of Science in International Business February 2017 © YANG GAO, 2017 Abstract In This study, I explore the effects of structures of technological alliance networks on firms’ exploratory knowledge creation. The research is built upon the connections between social network, organizational learning, and organizational ambidexterity theories. Firms pursue knowledge creation opportunities by forming technological alliances, but no consensus has been reached regarding the optimum strategy of alliance formation activities, i.e., whether the return of knowledge creation always increases in tandem with numbers of alliances or it diminishes at some point due to various factors such as costs of maintaining ties and capabilities of absorb information and knowledge generated from alliances. The study sheds light on the controversy of whether the relationship between network structures and knowledge creation is positive or curvilinear by distinguishing different orientations of knowledge creation activities, which entail different network structures and strategies. More specifically, by extracting exploratory knowledge creation from the overall knowledge creation activities, the relationship between basic network position features and exploration is more focused and accurate. Empirical investigation, which uses hand-collected data of alliance activities and patent application behaviors of 67 firms in several IT clusters in US, proves the curvilinear relationship between alliance network centrality and exploratory knowledge creation. Results of the study help to address the conflicts of networks’ effects on knowledge creation with new evidence from knowledge intensive industries, and provided insights on organizational learning and firm innovation strategies. -

6 GOLDEN “Mom, That’S a Great Poem, but I Need Some Money,” He Replied Quickly

KEVIN O’LEARY When Kevin graduated from the University of Waterloo with a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies, he was hit with a startling reality. He was cut off. THE O’LEARY FAMILY SECRETS When it happened his mother shared a bit of insight, “My mother said to me, ‘The dead bird under the nest is the one that never learned how to fly,’” 6 GOLDEN “Mom, that’s a great poem, but I need some money,” he replied quickly. But his days of being provided for were over, and he knew it was time to learn how to provide. “Woah, no dead bird for me,” he decided. Less than 10 years later he would start the software company SoftKey, that would RULES eventually become The Learning Company and be sold to Mattel for $4.2 billion. He credits his mother’s loving financial desertion for his individual success as he OF INVESTING presides over a multitude of companies bearing his last name: O’Leary Fine Wines, financial company O’Shares Investments, and private equity firm O’Leary Ventures. My Personal Plan for Financial Peace Kevin continues this practice with his own children, Trevor and Savannah. It’s import- ant to give people what they need, not just what they want. He says, “You can’t empower them, you can’t entitle them. You have to prepare people to go and do their own thing.” Kevin sees it as his responsibility as a successful entrepreneur to provide a road map for the next generation of hustlers. Not just of his successes, but his failures as well, so that they don’t have to keep making the same mistakes. -

MATTEL and the LEARNING COMPANY: a CASE of an ACQUISITION in TROUBLE Laurel Mitchell, Claremont Mckenna College, 500 E

MATTEL AND THE LEARNING COMPANY: A CASE OF AN ACQUISITION IN TROUBLE Laurel Mitchell, Claremont McKenna College, 500 E. Ninth Street, Claremont, CA 9171 I 1-909-607-3686, lmitchell@,mckenna edu ABSTRACT At yearond 1998, Mattel announced the acquisition of The Learning Company, the second largest consumer software publisher (Reader Rabbit, the Princeton Review test preparation series, etc.). The purchase price was $3.5 billion for The Learning Company, and Mattel amicipated transforming itself from a traditional toy company to a global provider of products for children. A mere sixteen months lat~, the acquisition was deemed a failure. In September 2000, MaRel announced the sale of the Learning Company unit, for almost no cash and the right to a share of the unit's future earnings. Along the way, the Learning Company unit lost up to $1 million per day under Mattel's leadership. This case, appropriate for Financial Statement Analysis or a capstone course, gives background on the industry, the acquisition and subsequent developments, and asks students to consider accounting and valuation issues relevant to the decisions to purchase and subsequently sell the Learning Company. DESCRIPTION OF COMPANIES AND INDUSTRIES The Learning Company was formed in 1994. Through more than a dozen acquisitions, by 1998 it was a giant in educational software, with over 500 titles including the Reader Rabbit and Princeton Review series. Revenue in 1998 totaled $839 million, making the Learning Compan); the second largest manufacturer of software (after Microsoft) and the leader in educational software with over a 40% market share. So, the Learning Company was well positioned as a leader in the fast growing (sales of $1.8 billion in 1998) educational and entertainment software industry. -

MTA--Art of Reading 2016-17.Pdf

ART OF READING 2016 -17 The book of books of Mondragon Team Academy The following pages contain lists on excellent books in the domains of personal development, coaching, learning, communities and teamwork, entrepreneurship, leadership, marketing and customers, innovation. They have been chosen on the basis of practicality and suitability in the context of entrepreneurial education and action. Part of this list is based on Johannes Partanen’s (Team Academy's Headcoach) recommendations and Mondragon Team Academy has added some fields and domains taking into account the social context of Mondragon University. The number indicates the book’s” literature point number”. The number varies from one to three. 1 point: Basic level book 2 points: More demanding book 3 points: Demanding book; it takes time to digest all the ideas presented in the book" The difficulty level is based both on the amount of work needed to apply the book’s ideas into practice and on theoretical difficulty. These points are used in various coaching programs and processes that use Mondragon Team Academy Methods to indicate and measure the amount of theory studies. This list is an open one and it will be updated every year with newest theories. At the same time most of the books they have a mark with start conecting how valuable is the book acording Johannes Partanen. * Ok. Nice book ** Excellent book *** Master piece !! At such recommendation is it totally subjective an you might have a different taste of books. BOOKS ON PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT, LEARNING, COMMUNITIES AND TEAMWORK "Know thyself. You have to explore yourself through your whole life. -

Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected]

July 2012 Fall of the Wall Deborah H. Quazzo Managing Partner Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected] Michael Cohn Vice President 1 (312) 397-1971 [email protected] Jason Horne Associate 1 (312) 397-0072 [email protected] Michael Moe Special Advisor 1 (650) 294-4780 [email protected] Global Silicon Valley Advisors gsvadvisors.com Table of Contents 1) Executive Summary 3 2) Education’s Emergence, Decline and Re-Emergence as an Investment Category 11 3) Disequilibrium Remains 21 4) Summary Survey Results 27 5) Interview Summaries 39 6) Unique Elements of 2011 and Beyond 51 7) Summary Conclusions 74 8) The GSV Education Innovators: 2011 GSV/ASU Education Innovation Summit Participants 91 2 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY American Revolution 2.0 Fall of the Wall: Capital Flows to Education Innovation Executive Summary § Approximately a year ago, GSV Advisors set out to analyze whether there is adequate innovation and entrepreneurialism in the education sector and, if not, whether a lack of capital was constraining education innovation § Our observations from research, interviews, and collective experience indicate that there is great energy and enthusiasm around the PreK-12, Post Secondary and Adult (“PreK to Gray”) education markets as they relate to innovation and the opportunity to invest in emerging companies at all stages § Investment volume in 2011 exceeded peak 1999 – 2000 levels, but is differentiated from this earlier period by entrepreneurial leaders with a breadth of experience including education, social media and technology; companies with vastly lower cost structures; improved education market receptivity to innovation, and elevated investor sophistication. -

E-Learning and Knowledge Technology: Changing the Way We

SunTrust Equitable Securities 7DEOHRI&RQWHQWV Technology & the Internet are Changing the Way We Learn............................................................................................ 3 The Power of the Internet ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 • Factors Driving Growth 5 • E-Commerce — The New Economy 5 • Computer and Bandwidth Growth 6 • The Result: A Growing User Base 8 The New Way of Learning ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 • The Education and Knowledge Market 10 • Learning Benefits Created by Technology and the Internet 12 • Which Business Models Will Prevail? 13 Content/Publishing — Providing the Information for Learning........................................................................................ 14 • K-12 Sector 15 • P2 Sector 17 • Corporate Training Sector 18 • Lifelong Learning Sector 20 Tools/Enablers — Providing the Platforms for Learning ................................................................................................. 21 • K-12 Sector 21 • P2 Sector 23 • Corporate Training Sector 24 • Lifelong Learning Sector 28 Learning Service Providers — Transforming Information into Knowledge.................................................................. 28 • K-12 Sector 29 • P2 Sector 31 • Corporate Training Sector 32 • Lifelong Learning Sector 35 Knowledge Hubs/Portals/Communities -

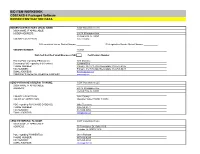

Bid Item Workbook Bidder/Contractor Data

BID ITEM WORKBOOK COSTARS-6 Packaged Software BIDDER/CONTRACTOR DATA BIDDER/CONTRACTOR'S LEGAL NAME: CDW Government LLC D/B/A NAME, IF APPLICABLE: BIDDER ADDRESS: 230 N. Milwaukee Ave. Vernon Hills, IL, 60061 COUNTY LOCATED IN: Lake County PA Legislative House District Number PA Legislative Senate District Number VENDOR NUMBER: 163101 DGS Self-Certified Small Business (SB) Certification Number Primary POC regarding IFB/Contract: Rick Martinez Secondary POC regarding IFB/Contract: Jumana Dihu PHONE NUMBER: Primary: 847-371-7182 Secondary: 312-547-2495 FAX NUMBER: Primary: 312 705-8649 Secondary: 312-705-9437 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] COMPANY'S GENERAL WEBSITE ADDRESS www.cdwg.com SEND PURCHASE ORDER(S) TO NAME: CDW Government LLC D/B/A NAME, IF APPLICABLE: ADDRESS: 230 N. Milwaukee Ave. Vernon Hills, IL, 60061 COUNTY LOCATED IN: Lake County HOURS OF OPERATION: Monday-Friday 7:00AM-7:30PM POC regarding PURCHASE ORDER(S): Mike Truncone PHONE NUMBER: 866-769-8471 FAX NUMBER: 847-990-8050 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] SEND PAYMENT(S) TO NAME: CDW Government LLC D/B/A NAME, IF APPLICABLE: ADDRESS: 75 Remittance Dr. Suite 1515 Chicago, IL, 60675-1515 POC regarding PAYMENT(S): Janet Pishotta PHONE NUMBER: 847-419-6284 FAX NUMBER: 847-465-6884 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] BID ITEM WORKBOOK COSTARS-6 Packaged Software QUESTIONS BIDDERS/CONTRACTOR'S LEGAL NAME: CDW Government LLC. PLEASE BE ADVISED - COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS AND EXPLANATIONS FOR YOUR BID TO BE ACCEPTED AS A RESPONSIBLE AND RESPONSIVE BID The bidder must answer the following questions: QUESTION YES NO EXPLANATION 1) Does the Bidder-Contractor have any minimum order requirements? If yes, please explain. -

Lessons from Merger and Acquisition Analysis

2012 2nd International Conference on Computer and Software Modeling (ICCSM 2012) IPCSIT vol. 54 (2012) © (2012) IACSIT Press, Singapore DOI: 10.7763/IPCSIT.2012.V54.14 Lessons from Merger and Acquisition Analysis Gurkirat Singh1 , Pankaj Maan1 and V.B. Khanapuri2 1Student, PGDIM, National Institute of Industrial Engineering (N I T I E), Vihar Lake, Mumbai, India 2Faculty, National Institute of Industrial Engineering (N I T I E), Vihar Lake, Mumbai, India Abstract. The Merger and Acquisitions (M&A‟s) activity is influenced by a multitude of factors (like strategic, behavioural, and economic). It is a particular aspect of the M&A process, where the acquirer holds a vision with its own distinctive competitive strategy, accordingly tries to dictate the future developments in the post-merger scenario. Consequently, the resulting post-merger entity undergoes evolution and partake some actions leading to strategic-fit cohesion. Also, such state of affairs directly affects different entities of the value chain. Developing on these lines, this paper tries to analyze M&A in different industries and identify the key factors that led to success/failures of these M&A‟s. Keywords: Mergers and Acquisitions, Reasons for failures, Business associations 1. Introduction During the last few decades the business landscape has been deeply impacted by the globalization. Firms can no longer expand by embracing part-by-part approach for diverse markets, while ignoring the spillover and transmission effect of the elements constituting the economic scene. The outlook needs to be comprehensive and prudent for surviving in today‟s business scene. Furthermore, the existence of multinational firms along with domestic ones makes the sustenance all the more challenging. -

The Dark Side of Leadership: Troubling Times at the Top / 1

THE DARK SIDE TROUBLiNg TiMES at ThE TOp OF LEADERSHIPINSIGHTS @ SEMANN & SLATTERY DISCUSSION PAPER SEMANN & SLATTERY • SYDNEY • MELBOURNE • WWW.SEMANNSLATTERY.COM SEMANN & SLATTERY • SYDNEY • MELBOURNE • WWW.SEMANNSLATTERY.COM AUTHOR: Colin Slattery PUBLICATION DATE: November 2009 CORRESPONDENCE: please direct all correspondence to [email protected] COPYRIGHT: This document is protected under copyright legislation. This document cannot be reproduced, wholly or partly, without prior written consent from Semann & Slattery ThE DARK SiDE OF LEADERShip: TROUBLiNg TiMES AT ThE TOp / 1 Abstract Spectacular failures of organisations such as WorldCom, Enron and Lenham This discussion paper has several purposes. First it argues that the ‘dark Bros have highlighted the dark side of leadership and the relationship side of leadership’ is ill defined and, depending on the scholar’s ideology, between leaders, followers and environmental factors. With 50 – 75% the definition becomes self-fulfilling. Second, it sets out the characteristics of leaders experiencing leadership problems or failures, the topic of the of the dark side of leadership and proposes a definition that encompasses dark side of leadership has been increasingly popularised in academic and leader, follower and situational factors that contribute to behaviour popular press. The definition of dark side of leadership in current literature associated with leadership failure more broadly. Third, the importance of is unclear. The causes of the dark side of leadership are multifaceted and power from personalised and socialised perspectives is discussed and it will are exposed through a combination of situational and behavioural factors be argued that personalised power motives result in negative outcomes. which impact on organisational outcomes. Fourth, it examines the main causes of the dark side of leadership including incompetence, laissez-faire leadership; problems with charismatic leaders Between 50 – 75% of leaders do not perform well or experience leadership and personality disorders.