Regional Inequalities and Spatial Economic Interdependence: Learning from the Greek Prefectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

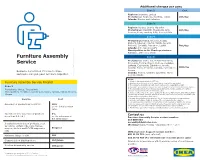

Assembly Leaflet AES ACS

Additional charges per zone Υπηρεσία Zone 2 Cost Regions: Ioannina, Larissa συναρμολόγησης επίπλων Prefectures: Magnesia, Karditsa, Trikala 20€/day Islands: Rhodes and Salamina Zone 3 Regions: Achaea, Chania, Heraklion Prefectures: Chalkidiki, Thesprotia, Arta, 40€/day Preveza, Pieria, Imathia, Pella, Serres, Kilkis Zone 4 Prefectures: Drama, Grevena, Kozani, Kastoria, Rhodope, Kavala, Xanthi, Boeotia, Phthiotis, Corinthia, Rethymno, Lasithi 70€/day © Islands: Argo-Saronic Gulf's Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2018 B.V. Inter IKEA Systems Municipalities in the Chania prefecture: Kantanos, Selino and Sfakia Furniture Assembly Zone 5 Prefectures: Corfu, Ilia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Service Evrytania, Florina, Phocis, Euboea, Cyclades, Lefkada, Cephalonia, Zakynthos, Argolis, Arcadia, Evros, Messinia, Laconia, Dodecanese, 100€/day Because sometimes it’s nice to have Lesbos Islands: Thasos, Cythera, Sporades, North someone else put your furniture together. Aegean islands Notes: 1. All above listed prices include VAT 24%. Furniture Assembly Service Pricelist 2. Furniture must be located to the space where they will be assembled. 3. The charge for an additional visit, due to customer’s responsibility, is 25€. Zone 1 4. Consumer is not obliged to pay if the notice of payment is not received (receipt-invoice). Prefectures: Attica, Thessaloniki 5. The assembly charge for products purchased from the As-Is Department or with a discount is calculated based on their initial value. Municipalities: Heraklion, Ioannina, Komotini, Larissa, Patras, Rhodes, 6. Disassembly service in the store, applies for the stores IKEA Airport, IKEA Kifissos, IKEA Chania Thessaloniki and IKEA Ioannina. Maximum waiting time is 2 hours. Service is available until 2 hours before closing time of the store. -

Government Spending on Regional Public Services in Greece: Spatial Distribution of Their Evolution Before and During the Financial Crisis

Government spending on regional public services in Greece: Spatial distribution of their evolution before and during the financial crisis. Anastasiou Eugenia1,*, Theodossiou George2, Thanou Eleni3 1 PhD Candidate, Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Greece 2Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, TEI of Thessaly 3Lecturer, Graduate Program on Banking, Hellenic Open University *Corresponding author: [email protected], Tel +30 24210 74433 Abstract Greece is still caught in a prolonged recession, which started in 2008. As a result, the economy continues to shrink, which has direct repercussions on the level of private and public consumption as well as on the level government's functions. The present paper attempts to record and depict spatially the evolution of the per capita public spending of the central government on regional services. The specific category of public spending represents a measure of relative welfare as well as a measure of regional development. For the purposes of the research we applied analytical methods such as descriptive statistics and we used specialized mapping analysis programs and geographical information systems (GIS). The evolution over time is observed on the basis of the annual percentage changes of per capita spending. The period of analysis is 2008-2013 and it includes years before the manifestation of the economic crisis as well as the years of the crisis' peak. The thematic maps that were constructed on the basis of the data clearly demonstrate that government spending on the regions was dramatically reduced during the crisis while the period during which the tightening of fiscal policy had a direct impact on the regions stands out. -

Rabiesrabies Eradicationeradication Programprogram 20142014

GreekGreek RabiesRabies EradicationEradication ProgramProgram 20142014 Directorate General of Sustainable Animal Production & Veterinary Services Animal Health Directorate Department of Zoonoses Brussels 9-10 September 2015 Epidemiological situation 9 May 2014: Detection of the last rabies case in a fox in the Regional Unit of Pella No further cases have been identified RabiesRabies CasesCases 20122012--todaytoday Regional Unit Animal Rabies Cases Kilkis**F 18 FAT & PCR Positive : 48 Pella* F 10 Serres* 1 40 2014 Thessaloniki*F 10 5 Kozani F 2 1 Trikala*F 5 Larisa* 1 * Domestic animal 2 ** Livestock Kastoria* 1 F fox(es) RabiesRabies CasesCases GreeceGreece -- 20142014 http://www.who-rabies-bulletin.org/Queries/Maps.aspx PassivePassive SurveillanceSurveillance datadata 20122012--JuneJune 20152015 Year Number of Samples 2012 237 2013 587 Annual target : 1100 2014 410 2015 (first semester) 138 PassivePassive SurveillanceSurveillance (total)(total) -- 20142014 PassivePassive SurveillanceSurveillance (domestic(domestic-- wildwild--bats)bats) -- 20142014 PassivePassive SurveillanceSurveillance samplessamples collectedcollected perper RegionalRegional UnitUnit (2014)(2014) Passive Surveillance – 2014 340 out of 410 animal samples (nervous tissue samples) belonged to indicatorsindicators ¾clinical signs ¾abnormal behaviour suspect of rabies ¾ found dead ¾ road kills ¾animals involved in human exposure In the remaining animals the cause of sampling was not mentioned or it was mentioned that the animal had been found poisoned Oral Red Foxes Vaccination -

ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS “Archaeological Tourism in Greece

UNIVERSITY OF THE PELOPONNESE ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS (R.N. 1012201502004) DIPLOMA THESIS: “Archaeological tourism in Greece: an analysis of quantitative data, determining factors and prospects” SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara EXAMINATION COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikolaos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara - Dr. Nikolaos Platis ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ, MARCH 2017 Abstract . For many decades now, Greece has invested a lot in tourism which can undoubtedly be considered the country’s most valuable asset and “heavy industry”. The country is gifted with a rich and diverse history, represented by a variety of cultural heritage sites which create an ideal setting for this particular type of tourism. Moreover, the variations in Greece’s landscape, cultural tradition and agricultural activity favor the development and promotion of most types of alternative types of tourism, such as agro-tourism, religious, sports and medicinal tourism. However, according to quantitative data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, despite the large number of visitors recorded in state-run cultural heritage sites every year, the distribution pattern of visitors presents large variations per prefecture. A careful examination of this data shows that tourist flows tend to concentrate in certain prefectures, while others enjoy little to no visitor preference. The main factors behind this phenomenon include the number and importance of cultural heritage sites and the state of local and national infrastructure, which determines the accessibility of sites. An effective analysis of these deficiencies is vital in order to determine solutions in order to encourage the flow of visitors to the more “neglected” areas. The present thesis attempts an in-depth analysis of cultural tourism in Greece and the factors affecting it. -

The Fourth Season of Danish-Greek Archaeological Fieldwork on the Lower Acropolis of Kalydon in Aitolia Has Now Been Underway for Two Weeks

The fourth season of Danish-Greek archaeological fieldwork on the Lower Acropolis of Kalydon in Aitolia has now been underway for two weeks. The fieldwork is a collaboration between the Danish Institute at Athens and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Aetolia-Acarnania and Lefkada in Messolonghi and directed by Dr. Søren Handberg, Associate Professor at the University of Oslo and the Ephor Dr. Olympia Vikatou. This year work focuses on the completion of the excavation of the Hellenistic house with a courtyard, which was first identified in 2013. During the past two weeks, the excavations have already produced significant new finds. In one room, where a collapsed roof has preserved the content of the room intact, fifteen small nails have been identified, which presumably originally belonged to a small wooden box kept inside the room. Last Friday, an Ionic column drum was excavated in an area that might be part of the courtyard of the house. A considerable amount of Roman Terra Sigillata pottery of the Augustan period has also been found, which is surprising since the ancient literary sources suggest that the city was abandoned at this time. The ongoing topographical survey of the entire ancient city has revealed approximately thirty previously undocumented structures, one of which might be a larger public building in the eastern part of the city. This year’s team comprises 50 people from Greece, Denmark, and Norway including students of archaeology from Aarhus University, the University of Copenhagen and the University of Oslo. The project is grateful to the Carlsberg Foundation for the continued financial support, which facilitates the fieldwork that is essential for establishing the ancient history of Kalydon and the region of Aitolia. -

Monitoring Geophysical Activity from Space, in the Framework Of

Monitoring geophysical activity from Space, in the framework of BEYOND Center of Excellence Ioannis Papoutsis1, Christina Psychogyiou1, Nikos Svigkas1, Maria Kaskara1, Charalampos Kontoes1, Athanassios Ganas2, Vassilis Karastathis2, George Balasis1, Aggeliki Barberopoulou1 Institute of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications & Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens Institute of Geodynamics, National Observatory of Athens A major objective of BEYOND Centre of Excellence is the operational monitoring of geohazards in Southeastern Europe. BEYOND primarily builds upon state-of-the-art optical remote sensing technologies and differential interferometry techniques. The resulting products are integrated with in-situ observations from the National Seismological Network, and the NOANET GPS network established at the National Observatory of Athens, to monitor the geodetic activity in Greece and beyond, interpret geophysical phenomena, assess and map damages after catastrophic events. Additionally, the ENIGMA magnetometer network is used in an attempt to address the issue of earthquake predictability by studying electromagnetic signals attributed to the coupled lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere system as one of the most promising potential pre-seismic transients. Characteristic examples of services offered in the framework of BEYOND will be highlighted, to address different phenomena and processes in Greece. Three thematic pillar services are offered on a systematic basis, namely ground deformation estimation following catastrophic earthquakes, time-series analysis for mapping ground velocity patterns and signals in large scale and damage assessment using UAV technology for prompt response during or immediately after a crisis. Persistent scatterer techniques are employed for a number of test sites. Firstly we discuss the 2011-2012 volcanic unrest in Santorini volcano. Using Envisat data, up to 15 cm/yr line- of-sight uplift was observed in the highly touristic villages of Fira and Imerovigli. -

ESPON ESCAPE Final Report Annex 11

ESCAPE European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance Applied Research Final Report – Annex 11 Case Study Kastoria, Western Macedonia, Greece Annex 11 This report is one of the deliverables of the ESCAPE project. This Applied ResearchProject is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Eleni Papadopoulou, Prof. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Faculty of Engineering, School of Spatial Planning and Development (Greece) Christos Papalexiou, Dr, Agricultural Engineer - Rural Economist Elena Kalantzi, Spatial Planing and Development Engineer Afroditi Basiouka, MSc, Spatial Planing and Development Engineer, Municipality of Tzumerka, Epirus (Greece) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Benoit Esmanne, DG Agriculture and Rural Development (EU), Izabela Ziatek, Ministry of Economic Development (Poland), Jana Ilcikova, Ministry of Transport and Construction (Slovakia), Amalia Virdol, Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration (Romania) ESPON EGTC: Gavin Daly, Nicolas Rossignol, -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

Stamna Hesperos.Pdf

Heirs of the Loom? Funerary Textiles from Stamna (Aitolia, Greece). A preliminary analysis Kolonas, Lazaros; Sarri, Kalliopi; Margariti, Christina; Vanden Berghe, Ina; Skals, I.; Nosch, Marie Louise Bech Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Kolonas, L., Sarri, K., Margariti, C., Vanden Berghe, I., Skals, I., & Nosch, M. L. B. (2017). Heirs of the Loom? Funerary Textiles from Stamna (Aitolia, Greece). A preliminary analysis. 533-544. Abstract from Hesperos. The Aegean seen from the West. , Ioannina, Greece. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 This pdf is a digital offprint of your contribution in M. Fotiadis, R. Laffineur, Y. Lolos & A. Vlachopoulos (eds), Hesperos. The Aegean Seen from the West, ISBN 978-90-429- 3562-4. The copyright on this publication belongs to Peeters Publishers. As author you are licensed to make printed copies of the pdf or to send the unaltered pdf file to up to 50 relations. You may not publish this pdf on the World Wide Web – including websites such as academia.edu and open-access repositories – until three years after publication. Please ensure that anyone receiving an offprint from you observes these rules as well. If you wish to publish your article immediately on open- access sites, please contact the publisher with regard to the payment of the article processing fee. For queries about offprints, copyright and republication of your article, please contact the publisher via [email protected] AEGAEUM 41 Annales liégeoises et PASPiennes d’archéologie égéenne ΕΣΠΕΡΟΣ / ΗESPEROS THE AEGEAN SEEN FROM THE WEST Proceedings of the 16th International Aegean Conference, University of Ioannina, Department of History and Archaeology, Unit of Archaeology and Art History, 18-21 May 2016 Edited by Michael FOTIADIS, Robert LAFFINEUR, Yannos LOLOS, and Andreas VLACHOPOULOS PEETERS LEUVEN -LIÈGE 2017 CONTENTS Preface ix KEYNOTE LECTURE Sebastiano TUSA The Ancient and Long History of East, Central and West Mediterranean Sea Routes 3 I. -

List of Designated Points of Import in Greece

List of Designated Points of Import for Food in Greece 1. Port of Pireus . Warehouse PCDC, Pireus Consolidation and Distribution Center, N.Ikonio, Perama Attikis . Warehouse C4, Pireus Port Authority SA, N.Ikonio, Perama Attikis . Warehouse C3 and C5 of Pireus Port Organisation SA, Keratsini Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2104009997 email: [email protected] 2 Athens International Airport “Eleftherios Venizelos” Building 26A, Athens International Airport, Spata Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2103538456 / 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2103538457, 2104009997 email: [email protected] / [email protected] 3 Athens Customs of Athens, Metamorfosi Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2104009997 email: [email protected] 4 Port of Thessaloniki APENTOMOTIRIO, 26th Octovriou, Gate 12, p.c.54627, Organismos Limena Thessalonikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Thessaloniki tel: (+30) 2310547749 Fax: (+30) 2310476663 / 2310547749 email: [email protected] 5 Thessaloniki International Airport “Makedonia” Thermi, Thessaloniki CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Thessaloniki tel: (+30) 2310547749 Fax: (+30) 2310476663 / 2310547749 email: -

In Focus: Corfu, Greece

OCTOBER 2019 IN FOCUS: CORFU, GREECE Manos Tavladorakis Analyst Pavlos Papadimitriou, MRICS Director www.hvs.com HVS ATHENS | 17 Posidonos Ave. 5th Floor, 17455 Alimos, Athens, GREECE Introduction The region of the Ionian Islands consists of the islands in the Ionian Sea on the western coast of Greece. Since they have long been subject to influences from Western Europe, the Ionian Islands form a separate historic and cultural unit than that of continental Greece. The region is divided administratively into four prefectures (Corfu, Lefkada, Kefallinia and Zakinthos) and comprises the islands of Kerkira (Corfu), Zakinthos, Cephalonia (Kefallinia), Lefkada, Ithaca (Ithaki), Paxi, and a number of smaller islands. The Ionian Islands are the sunniest part of Greece, but the southerly winds bring abundant rainfall. The region is noted for its natural beauty, its long history, and cultural tradition. It is also well placed geographically, since it is close to both mainland Greece and Western Europe and thus forms a convenient stepping-stone, particularly for passenger traffic between Greece and the West. These factors have favored the continuous development of tourism, which has become the most dynamic branch of the region’s economy. Island of Corfu CORFU MAP Corfu is located in the northwest part of Greece, with a size of 593 km2 and a costline, which spans for 217 km, is the largest of the Ionian Islands. The principal city of the island and seat of the municipality is also named Corfu, after the island’s name, with a population of 32,000 (2011 census) inhabitants. Currently, according to real estate agents, foreign nationals who permanently reside on Corfu are estimated at 18,000 individuals.