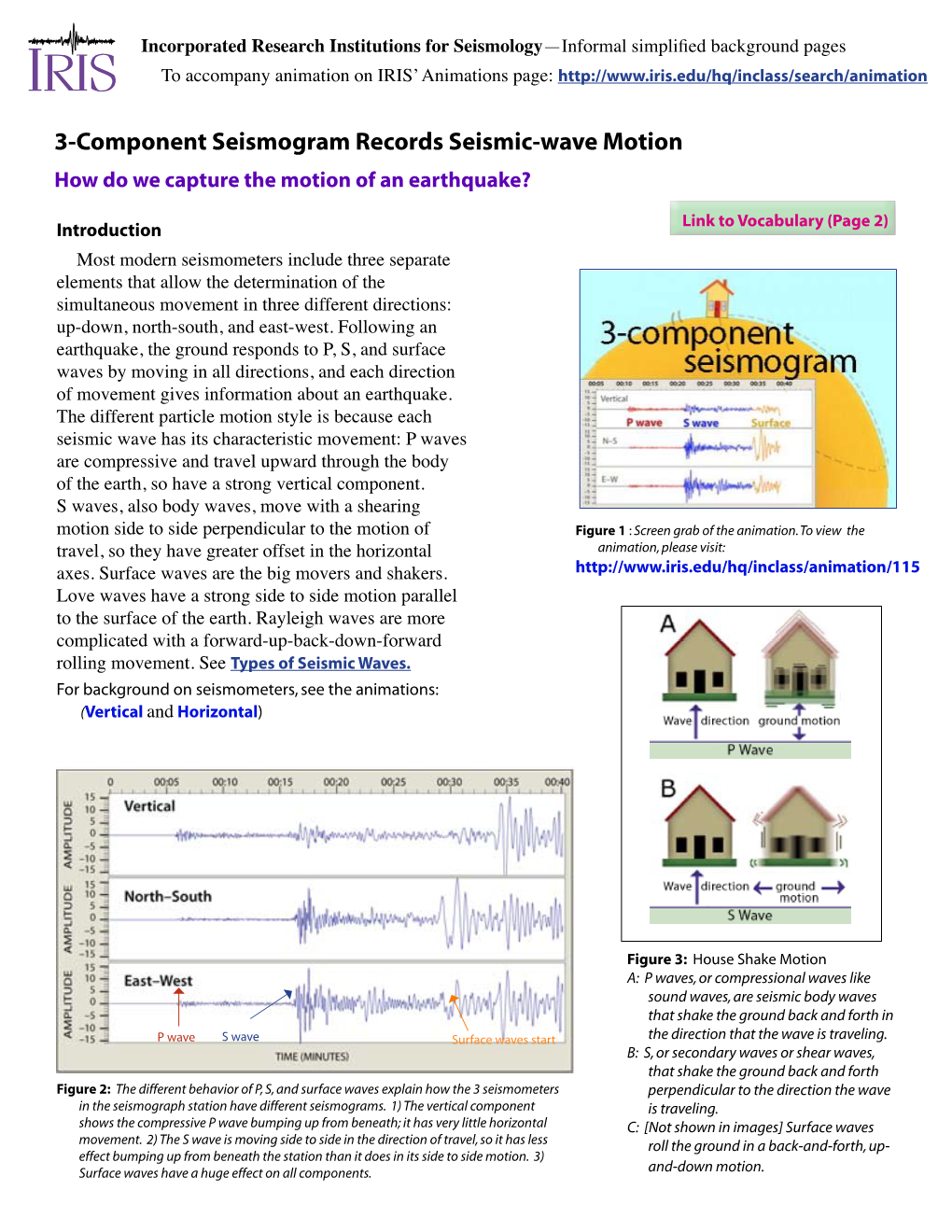

3-Component Seismogram Records Seismic-Wave Motion How Do We Capture the Motion of an Earthquake?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keck Combined Strong-Motion/Broadband Obs

KECK COMBINED STRONG-MOTION/BROADBAND OBS WHOI Ocean Bottom Seismograph Laboratory W.M. Keck Foundation Award to Understand Earthquake Predictability at East Pacific Rise Transform Faults. • In 2006, the W.M. Keck Foundation awarded funding to Jeff McGuire and John Collins to determine the physical mechanisms responsible for the observed capability to predict, using foreshocks, large (Mw ~6) transform-fault earthquakes at the East Pacific Rise, and to gain greater insight into the fundamentals of earthquake mechanics in general. • Achieving this objective required building 10 OBS of a new and unique type that could record, without saturation, the large ground motions generated by moderate to large earthquakes at distances of less than ~10 km. W.M. Keck OBS: Combined Broadband Seismometer and Strong-Motion Accelerometer • The broadband OBS available from OBSIP carry a broadband seismometer whose performance is optimized to resolve the earth’s background noise, which can be as small as 10-11 g r.m.s. in a bandwidth of width 1/6 decade at periods of about 100 s. Thus, these sensors are ideal for resolving ground motions from large distant earthquakes, necessary for structural seismology studies. • Ground motions from local, moderate to large earthquakes can generate accelerations of up a g or more, which would saturate or clip these sensors. Currently, there are no sensors (or data-loggers) that have a dynamic range to resolve this ~220 dB range of ground motion. • To overcome this limitation, we used Keck Foundation funding to build 10 OBS equipped with both a conventional broadband seismometer and a strong- motion accelerometer with a clip level of 2.5 g. -

Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on the Dynamic Mechanical Behavior Of

EFFECT OF FABRIC ANISOTROPY ON THE DYNAMIC MECHANICAL BEHAVIOR OF GRANULAR MATERIALS by Bo Li Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Prof. Xiangwu Zeng Department of Civil Engineering Case Western Reserve University January, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Bo Li Candidate for Ph. D. degree*. (signed) Xiangwu Zeng Chair of Commitee Adel Saada Wojbor A. Woyczynski Xiong Yu (date) 11/15/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein Table of Contents Table of Contents I List of Tables IV List of Figures VI Acknowledgement XI Abstract XII Notation XIV Chapter 1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 Effect of Anisotropy on Granular Materials ........................................................................... 1 1.2 Research Objectives ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Outline of the Dissertation ...................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Review of the Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on Clay ............................................................... 3 1.4.1 Experimental Study on Effect of Fabric Anisotropy on Clay ......................................... 3 1.4.2 Analytical Method on Effect of Fabric Anisotropy -

Confidential Manuscript Submitted to Engineering Geology

Confidential manuscript submitted to Engineering Geology 1 Landslide monitoring using seismic refraction tomography – The 2 importance of incorporating topographic variations 3 J S Whiteley1,2, J E Chambers1, S Uhlemann1,3, J Boyd1,4, M O Cimpoiasu1,5, J L 4 Holmes1,6, C M Inauen1, A Watlet1, L R Hawley-Sibbett1,5, C Sujitapan2, R T Swift1,7 5 and J M Kendall2 6 1 British Geological Survey, Environmental Science Centre, Nicker Hill, Keyworth, 7 Nottingham, NG12 5GG, United Kingdom. 2 School of Earth Sciences, University 8 of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, United 9 Kingdom. 3 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Earth and 10 Environmental Sciences Area, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, United 11 States of America. 4 Lancaster Environment Center (LEC), Lancaster University, 12 Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, United Kingdom 5 Division of Agriculture and Environmental 13 Science, School of Bioscience, University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington, 14 Leicestershire, LE12 5RD, United Kingdom 6 Queen’s University Belfast, School of 15 Natural and Built Environment, Stranmillis Road, Belfast, BT9 5AG, United 16 Kingdom 7 University of Liege, Applied Geophysics, Department ArGEnCo, 17 Engineering Faculty, B52, 4000 Liege, Belgium 18 19 Corresponding author: Jim Whiteley ([email protected]) 20 21 Copyright British Geological Survey © UKRI 2020/ University of Bristol 2020 22 1 Confidential manuscript submitted to Engineering Geology 23 Abstract 24 Seismic refraction tomography provides images of the elastic properties of 25 subsurface materials in landslide settings. Seismic velocities are sensitive to 26 changes in moisture content, which is a triggering factor in the initiation of many 27 landslides. -

On the Wave Bottom Shear Stress in Shallow Depths: the Role of Wave Period and Bed Roughness

water Article On the Wave Bottom Shear Stress in Shallow Depths: The Role of Wave Period and Bed Roughness Sara Pascolo *, Marco Petti and Silvia Bosa Dipartimento Politecnico di Ingegneria e Architettura, University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (S.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0432-558-713 Received: 6 September 2018; Accepted: 25 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: Lagoons and coastal semi-enclosed basins morphologically evolve depending on local waves, currents, and tidal conditions. In very shallow water depths, typical of tidal flats and mudflats, the bed shear stress due to the wind waves is a key factor governing sediment resuspension. A current line of research focuses on the distribution of wave shear stress with depth, this being a very important aspect related to the dynamic equilibrium of transitional areas. In this work a relevant contribution to this study is provided, by means of the comparison between experimental growth curves which predict the finite depth wave characteristics and the numerical results obtained by means a spectral model. In particular, the dominant role of the bottom friction dissipation is underlined, especially in the presence of irregular and heterogeneous sea beds. The effects of this energy loss on the wave field is investigated, highlighting that both the variability of the wave period and the relative bottom roughness can change the bed shear stress trend substantially. Keywords: finite depth wind waves; bottom friction dissipation; friction factor; tidal flats; bottom shear stress 1. Introduction The morphological evolution of estuarine and coastal lagoon environments is a widely discussed topic in literature, because of its complexity and the great variability of morphological patterns. -

STRUCTURE of EARTH S-Wave Shadow P-Wave Shadow P-Wave

STRUCTURE OF EARTH Earthquake Focus P-wave P-wave shadow shadow S-wave shadow P waves = Primary waves = Pressure waves S waves = Secondary waves = Shear waves (Don't penetrate liquids) CRUST < 50-70 km thick MANTLE = 2900 km thick OUTER CORE (Liquid) = 3200 km thick INNER CORE (Solid) = 1300 km radius. STRUCTURE OF EARTH Low Velocity Crust Zone Whole Mantle Convection Lithosphere Upper Mantle Transition Zone Layered Mantle Convection Lower Mantle S-wave P-wave CRUST : Conrad discontinuity = upper / lower crust boundary Mohorovicic discontinuity = base of Continental Crust (35-50 km continents; 6-8 km oceans) MANTLE: Lithosphere = Rigid Mantle < 100 km depth Asthenosphere = Plastic Mantle > 150 km depth Low Velocity Zone = Partially Melted, 100-150 km depth Upper Mantle < 410 km Transition Zone = 400-600 km --> Velocity increases rapidly Lower Mantle = 600 - 2900 km Outer Core (Liquid) 2900-5100 km Inner Core (Solid) 5100-6400 km Center = 6400 km UPPER MANTLE AND MAGMA GENERATION A. Composition of Earth Density of the Bulk Earth (Uncompressed) = 5.45 gm/cm3 Densities of Common Rocks: Granite = 2.55 gm/cm3 Peridotite, Eclogite = 3.2 to 3.4 gm/cm3 Basalt = 2.85 gm/cm3 Density of the CORE (estimated) = 7.2 gm/cm3 Fe-metal = 8.0 gm/cm3, Ni-metal = 8.5 gm/cm3 EARTH must contain a mix of Rock and Metal . Stony meteorites Remains of broken planets Planetary Interior Rock=Stony Meteorites ÒChondritesÓ = Olivine, Pyroxene, Metal (Fe-Ni) Metal = Fe-Ni Meteorites Core density = 7.2 gm/cm3 -- Too Light for Pure Fe-Ni Light elements = O2 (FeO) or S (FeS) B. -

Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conferences on Recent Advances 2010 - Fifth International Conference on Recent in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Soil Dynamics Engineering and Soil Dynamics 26 May 2010, 4:45 pm - 6:45 pm Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method Sumit Ghose Bengal Engineering and Science University, India Ambarish Ghosh Bengal Engineering and Science University, India Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Ghose, Sumit and Ghosh, Ambarish, "Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential of Soil by Down Borehole Method" (2010). International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. 15. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd/05icrageesd/session01/15 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF LIQUEFACTION -

Defining P-Wave and S-Wave Stratal Surfaces with Nine-Component Vsps

INTERPRETER’S CORNER Coordinated by Rebecca B. Latimer Defining P-wave and S-wave stratal surfaces with nine-component VSPs BOB A. HARDAGE, MICHAEL DEANGELO, and PAUL MURRAY, Bureau of Economic Geology, Austin, Texas, U.S. Nine-component vertical seismic profile (9C VSP) data were acquired across a three-state area (Texas, Kansas, Colorado) to evaluate the relative merits of imaging Morrow and post-Morrow stratigraphy with compressional (P-wave) seismic data and shear (S-wave) seismic data. 9C VSP data generated using three orthogonal vector sources were used in this study rather than 3C data generated by only a ver- tical-displacement source because the important SH shear mode would not have been available if only the latter had been acquired. The popular SV converted mode (or C wave) utilized in 3C seismic technology is created by P-to-SV mode conversions at nonvertical angles of incidence at subsurface interfaces rather than propagating directly from an SV source as in 9C data acquisition. In contrast, 9C acquisition generates a P-wave mode and both fundamental S-wave modes (SH and SV) directly at the source station and allows these three basic compo- nents of the elastic seismic wavefield to be isolated from each other for imaging purposes. The purpose of these field tests was to compare SH, SV, and P reflectivity at targeted inter- faces. Because C waves were not an imaging objective, we used zero-offset acquisition geometry, which caused C-wave reflectivity to be quite small. We consider zero offset a source- to-receiver offset that is less than one-tenth of the depth to the shallowest receiver station. -

Summary of the New W4300 Course in DEES: “The Earth's Deep Interior” Instructor: Paul G

Summary of the new W4300 course in DEES: “The Earth's Deep Interior” Instructor: Paul G. Richards ([email protected]) This course emphasizes the geophysical study of Earth structure below the crust, drawing upon geodesy, geomagnetism, gravity, thermal studies, seismology, and some geochemistry. It covers the principal techniques by which discoveries have been made in deep Earth structure, and describes particular features of the mantle, and fluid and solid cores, such as: • the upper mantle beneath old and young oceans and continents • the transition zone in the mantle between about 400 and 700 km depth (within which density and elastic moduli increase anomalously with depth), • the lowermost mantle and core/mantle boundary (across which density doubles and sound speed halves), and • the outer core/inner core boundary (discovered by seismology, and profoundly affecting the Earth's magnetic field). The course is part of the core curriculum for graduate students in solid Earth geophysics and marine geophysics, is an elective for solid Earth geochemistry and geology, and is accessible to undergraduate science majors with adequate math and physics. The course, together with EESC W 4950x (Math Methods in the Earth Sciences), replaces the previous W 4945x – 4946y (Geophysical Theory I and II). It includes parts of previous courses (no longer listed) in seismology, geomagnetism, and thermal history. Emphasis is on current structure, rather than evaluation of dynamic processes (such as convection). Prerequisites calculus, differential -

Seismic Wavefield Imaging of Earth's Interior Across Scales

TECHNICAL REVIEWS Seismic wavefield imaging of Earth’s interior across scales Jeroen Tromp Abstract | Seismic full- waveform inversion (FWI) for imaging Earth’s interior was introduced in the late 1970s. Its ultimate goal is to use all of the information in a seismogram to understand the structure and dynamics of Earth, such as hydrocarbon reservoirs, the nature of hotspots and the forces behind plate motions and earthquakes. Thanks to developments in high- performance computing and advances in modern numerical methods in the past 10 years, 3D FWI has become feasible for a wide range of applications and is currently used across nine orders of magnitude in frequency and wavelength. A typical FWI workflow includes selecting seismic sources and a starting model, conducting forward simulations, calculating and evaluating the misfit, and optimizing the simulated model until the observed and modelled seismograms converge on a single model. This method has revealed Pleistocene ice scrapes beneath a gas cloud in the Valhall oil field, overthrusted Iberian crust in the western Pyrenees mountains, deep slabs in subduction zones throughout the world and the shape of the African superplume. The increased use of multi- parameter inversions, improved computational and algorithmic efficiency , and the inclusion of Bayesian statistics in the optimization process all stand to substantially improve FWI, overcoming current computational or data- quality constraints. In this Technical Review, FWI methods and applications in controlled- source and earthquake seismology are discussed, followed by a perspective on the future of FWI, which will ultimately result in increased insight into the physics and chemistry of Earth’s interior. -

Earthquake Measurements

EARTHQUAKE MEASUREMENTS The vibrations produced by earthquakes are detected, recorded, and measured by instruments call seismographs1. The zig-zag line made by a seismograph, called a "seismogram," reflects the changing intensity of the vibrations by responding to the motion of the ground surface beneath the instrument. From the data expressed in seismograms, scientists can determine the time, the epicenter, the focal depth, and the type of faulting of an earthquake and can estimate how much energy was released. Seismograph/Seismometer Earthquake recording instrument, seismograph has a base that sets firmly in the ground, and a heavy weight that hangs free2. When an earthquake causes the ground to shake, the base of the seismograph shakes too, but the hanging weight does not. Instead the spring or string that it is hanging from absorbs all the movement. The difference in position between the shaking part of the seismograph and the motionless part is Seismograph what is recorded. Measuring Size of Earthquakes The size of an earthquake depends on the size of the fault and the amount of slip on the fault, but that’s not something scientists can simply measure with a measuring tape since faults are many kilometers deep beneath the earth’s surface. They use the seismogram recordings made on the seismographs at the surface of the earth to determine how large the earthquake was. A short wiggly line that doesn’t wiggle very much means a small earthquake, and a long wiggly line that wiggles a lot means a large earthquake2. The length of the wiggle depends on the size of the fault, and the size of the wiggle depends on the amount of slip. -

BY JOHNATHAN EVANS What Exactly Is an Earthquake?

Earthquakes BY JOHNATHAN EVANS What Exactly is an Earthquake? An Earthquake is what happens when two blocks of the earth are pushing against one another and then suddenly slip past each other. The surface where they slip past each other is called the fault or fault plane. The area below the earth’s surface where the earthquake starts is called the Hypocenter, and the area directly above it on the surface is called the “Epicenter”. What are aftershocks/foreshocks? Sometimes earthquakes have Foreshocks. Foreshocks are smaller earthquakes that happen in the same place as the larger earthquake that follows them. Scientists can not tell whether an earthquake is a foreshock until after the larger earthquake happens. The biggest, main earthquake is called the mainshock. The mainshocks always have aftershocks that follow the main earthquake. Aftershocks are smaller earthquakes that happen afterwards in the same location as the mainshock. Depending on the size of the mainshock, Aftershocks can keep happening for weeks, months, or even years after the mainshock happened. Why do earthquakes happen? Earthquakes happen because all the rocks that make up the earth are full of fractures. On some of the fractures that are known as faults, these rocks slip past each other when the crust rearranges itself in a process known as plate tectonics. But the problem is, rocks don’t slip past each other easily because they are stiff, rough and their under a lot of pressure from rocks around and above them. Because of that, rocks can pull at or push on each other on either side of a fault for long periods of time without moving much at all, which builds up a lot of stress in the rocks. -

Characteristics of Foreshocks and Short Term Deformation in the Source Area of Major Earthquakes

Characteristics of Foreshocks and Short Term Deformation in the Source Area of Major Earthquakes Peter Molnar Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 USGS CONTRACT NO. 14-08-0001-17759 Supported by the EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS REDUCTION PROGRAM OPEN-FILE NO.81-287 U.S. Geological Survey OPEN FILE REPORT This report was prepared under contract to the U.S. Geological Survey and has not been reviewed for conformity with USGS editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Opinions and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the USGS. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USGS. Appendix A A Study of the Haicheng Foreshock Sequence By Lucile Jones, Wang Biquan and Xu Shaoxie (English Translation of a Paper Published in Di Zhen Xue Bao (Journal of Seismology), 1980.) Abstract We have examined the locations and radiation patterns of the foreshocks to the 4 February 1978 Haicheng earthquake. Using four stations, the foreshocks were located relative to a master event. They occurred very close together, no more than 6 kilo meters apart. Nevertheless, there appear to have been too clusters of foreshock activity. The majority of events seem to have occurred in a cluster to the east of the master event along a NNE-SSW trend. Moreover, all eight foreshocks that we could locate and with a magnitude greater than 3.0 occurred in this group. The're also "appears to be a second cluster of foresfiocks located to the northwest of the first. Thus it seems possible that the majority of foreshocks did not occur on the rupture plane of the mainshock, which trends WNW, but on another plane nearly perpendicualr to the mainshock.