Here We Are: Spatial Personalization and Inhabitance in Byron and Lovecraft”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O-Iwa's Curse

O-Iwa’s Curse Apparitions and their After-Effects in the Yotsuya kaidan Saitō Takashi 齋藤 喬 Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture In traditional Japanese theater, ghosts appear in the shadowlands between the visible and the invisible. They often try to approach those who harmed or abused them in life to seek revenge with the aid of supernatural powers. In such scenes, the dead are visible as a sign of impending doom only to those who are the target of their revenge. An examination of the Yotsuya kaidan, one of the most famous ghost stories in all of Japanese literature, is a case in point. The story is set in the Edo period, where the protagonist, O-Iwa, is reputed to have put a curse on those around her with catastrophic results. Her legend spread with such effect that she was later immortalized in a Shinto shrine bearing her name. In a word, so powerful and awe-inspiring was her curse that she not only came to be venerated as a Shinto deity but was even memorialized in a Buddhist temple. There is no doubt that a real historical person lay behind the story, but the details of her life have long since been swallowed up in the mists of literary and artistic imagination. In this article, I will focus on the rakugo (oral performance) version of the tale (translated into English by James S. de Benneville in 1917) and attempt to lay out the logic of O-Iwa’s apparitions from the viewpoint of the narrative. ho is O-Iwa? This is the name of the lady of Tamiya house, which appeared in the official documents of Tokugawa Shogunate. -

Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2015 The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho Eric Fischbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fischbach, Eric, "The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho" (2015). Masters Theses. 146. https://doi.org/10.7275/6499369 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/146 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2015 Asian Languages and Literatures - Japanese © Copyright by Eric D. Fischbach 2015 All Rights Reserved THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Amanda C. Seaman, Chair __________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Program Head Asian Languages and Literatures ________________________________________ William Moebius, Department Head Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all my professors that helped me grow during my tenure as a graduate student here at UMass. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

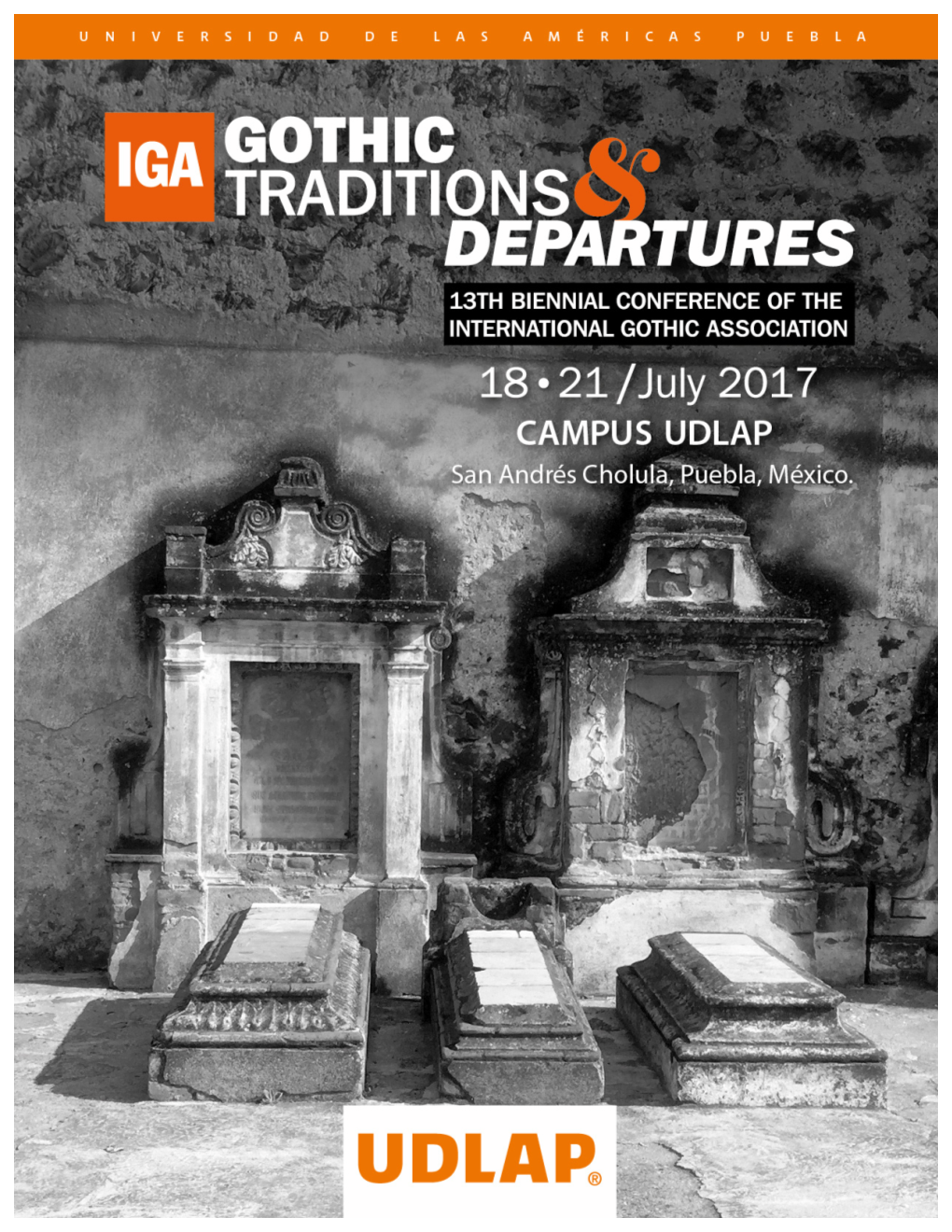

13Th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association

13th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association: Gothic Traditions and Departures Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP) 18 – 21 July 2017 Conference Draft Programme 1 Conference Schedule Tuesday 18 July 10:00 – 18:00 hrs: Registration, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins (Foyer). 15:00 – 15:30 hrs: Welcome remarks, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofia Jenkins. 15:30 – 16:45 hrs: Opening Plenary Address, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins: Isabella Van Elferen (Kingston University) Dark Sound: Reverberations between Past and Future 16:45 – 18:15 hrs: PARALLEL PANELS SESSION A A1: Scottish Gothic Carol Margaret Davison (University of Windsor): “Gothic Scotland/Scottish Gothic: Theorizing a Scottish Gothic “tradition” from Ossian and Otranto and Beyond” Alison Milbank (University of Nottingham): “Black books and Brownies: The Problem of Mediation in Scottish Gothic” David Punter (University of Bristol): “History, Terror, Tourism: Peter May and Alan Bilton” A2: Gothic Borders: Decolonizing Monsters on the Borderlands Cynthia Saldivar (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley): “Out of Darkness: (Re)Defining Domestic Horror in Americo Paredes's The Shadow” Orquidea Morales (University of Michigan): “Indigenous Monsters: Border Horror Representation of the Border” William A. Calvo-Quirós (University of Michigan): “Border Specters and Monsters of Transformation: The Uncanny history of the U.S.-Mexico Border” A3: Female Gothic Departures Deborah Russell (University of York): “Gendered Traditions: Questioning the ‘Female Gothic’” Eugene -

After Fantastika Programme

#afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com After Fantastika July 6/7th, Lancaster University, UK Schedule Friday 6th 8.45 – 9.30 Registration (Management School Lecture Theatre 11/12) 9.30 – 10.50 Panels 1A & 1B 11.00 – 12.20 Panels 2A, 2B & 2C 12.30 – 1.30 Lunch 1.30 – 2.45 Keynote – Caroline Edwards 3.00 – 4.20 Panels 3A & 3B 4.30 – 6.00 Panels 4A & 4B Saturday 7th 10.30 – 12.00 Panels 5A & 5B 12.00 – 1.00 Lunch 1.00 – 2.15 Keynote – Andrew Tate 2.30 – 3.45 Panels 6A, 6B & 6C 4.00 – 5.00 Roundtable 5.00 Closing Remarks Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who has helped contribute to either the journal or conference since they began, we massively appreciate your continued support and enthusiasm. We would especially like to thank the Department of English and Creative Writing for their backing – in particular Andrew Tate, Brian Baker, Catherine Spooner and Sara Wasson for their assistance in promoting and supporting these events. A huge thank you to all of our volunteers, chairs, and helpers without which these conferences would not be able to run as smoothly as they always have. Lastly, the biggest thanks of all must go to Chuckie Palmer-Patel who, although sadly not attending the conference in-person, has undoubtedly been an integral part of bringing together such a vibrant and engaging community – while we are all very sad that she cannot be here physically, you can catch her digital presence in panel 6B – technology willing! Thank you Kerry Dodd and Chuckie Palmer-Patel Conference Organisers #afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Fantasy Magazine, Issue 60 (People of Colo(U)R Destroy Fantasy

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 60, December 2016 People of Colo(u)r Destroy Fantasy! Special Issue FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner People of Colo(u)r Editorial Roundtable POC Destroy Fantasy! Editors ORIGINAL SHORT FICTION edited by Daniel José Older Black, Their Regalia Darcie Little Badger (illustrated by Emily Osborne) The Rock in the Water Thoraiya Dyer The Things My Mother Left Me P. Djèlí Clark (illustrated by Reimena Yee) Red Dirt Witch N.K. Jemisin REPRINT SHORT FICTION selected by Amal El-Mohtar Eyes of Carven Emerald Shweta Narayan gezhizhwazh Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (illustrated by Ana Bracic) Walkdog Sofia Samatar Name Calling Celeste Rita Baker NONFICTION edited by Tobias S. Buckell Learning to Dream in Color Justina Ireland Give Us Back Our Fucking Gods Ibi Zoboi Saving Fantasy Karen Lord We Are More Than Our Skin John Chu Crying Wolf Chinelo Onwualu You Forgot to Invite the Soucouyant Brandon O’Brien Still We Write Erin Roberts Artists’ Gallery Reimena Yee, Emily Osborne, Ana Bracic AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS edited by Arley Sorg Darcie Little Badger Thoraiya Dyer P. Djèlí Clark N.K. Jemisin Shweta Narayan Leanne Betasamosake Simpson Sofia Samatar Celeste Rita Baker MISCELLANY Subscriptions & Ebooks Special Issue Staff © 2016 Fantasy Magazine Cover by Emily Osborne Ebook Design by John Joseph Adams www.fantasy-magazine.com FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner | 187 words Welcome to issue sixty of Fantasy Magazine! As some of you may know, Fantasy Magazine ran from 2005 until December 2011, at which point it merged with her sister magazine, Lightspeed. Once a science fiction-only market, since the merger, Lightspeed has been bringing the world four science fiction stories and four fantasy shorts every month. -

The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of the Lost Decade, Jessica

The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan “Our Fear Has Taken on a Life of its Own”: The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of The Lost Decade, Jessica Balanzategui University of Melbourne, Australia 0168 The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract The monstrous child of Japanese horror film has become perhaps the most transnationally recognisable and influential horror trope of the past decade following the release of “Ring” (Hideo Nakata, 1999), Japan’s most commercially successful horror film. Through an analysis of “Ring”, “The Grudge” (Takashi Shimizu, 2002), “Dark Water” (Nakata, 2002), and “One Missed Call” (Takashi Miike, 2003), I argue that the monstrous children central to J-horror film of the millenial transition function as anomalies within the symbolic framework of Japan’s national identity. These films were released in the aftermath of the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in the early 1990s — a period known in Japan as ‘The Lost Decade’— and also at the liminal juncture represented by the turn of the millennium. At this cultural moment when the unity of national meaning seems to waver, the monstrous child embodies the threat of symbolic collapse. In alignment with Noël Carroll’s definition of the monster, these children are categorically interstitial and formless: Sadako, Toshio, Mitsuko and Mimiko invoke the wholesale destruction of the boundaries which separate victim/villain, past/present and corporeal/spectral. Through their disturbance to ontological categories, these children function as monstrous incarnations of the Lacanian gaze. As opposed to allowing the viewer a sense of illusory mastery, the J- horror monster-child figures a disruption to the spectator’s sense of power over the films’ diegetic worlds. -

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema a Thesis

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jordan G. Parrish August 2017 © 2017 Jordan G. Parrish. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema by JORDAN G. PARRISH has been approved for the Film Division and the College of Fine Arts by Ofer Eliaz Assistant Professor of Film Studies Matthew R. Shaftel Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract PARRISH, JORDAN G., M.A., August 2017, Film Studies The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema Director of Thesis: Ofer Eliaz This thesis argues that Japanese Horror films released around the turn of the twenty- first century define a new mode of subjectivity: “undead subjectivity.” Exploring the implications of this concept, this study locates the undead subject’s origins within a Japanese recession, decimated social conditions, and a period outside of historical progression known as the “Lost Decade.” It suggests that the form and content of “J- Horror” films reveal a problematic visual structure haunting the nation in relation to the gaze of a structural father figure. In doing so, this thesis purports that these films interrogate psychoanalytic concepts such as the gaze, the big Other, and the death drive. This study posits themes, philosophies, and formal elements within J-Horror films that place the undead subject within a worldly depiction of the afterlife, the films repeatedly ending on an image of an emptied-out Japan invisible to the big Other’s gaze. -

Kurosawa Kiyoshi Profile Prepared by Richard Suchenski Articles Translated by Kendall Heitzman Profile

Kurosawa Kiyoshi Profile prepared by Richard Suchenski Articles translated by Kendall Heitzman Profile Born in Kobe in 1955, Kurosawa Kiyoshi became interested in filmmaking as an elementary school student after he saw films by Italian horror filmmakers Mario Bava and Gorgio Ferroni. He formed a filmmaking club in high school and made his first Super 8mm short film, Rokkô, in 1973. Kurosawa continued making short 8mm films as a student at Rikkyô University, where he began to attend classes on cinema taught by Hasumi Shigehiko, the most important film critic and theorist of his era. Hasumi’s auteurist approach and deep admiration for American cinema of the 1950s deeply influenced a generation of Rikkyô students that, in addition to Kurosawa, included Suo Masayuki, Shiota Akihiko, Aoyama Shinji, and Shinozaki Makoto. While still a student, Kurosawa won a prize for his film Student Days at the Pia Film Festival in 1978. After presenting Vertigo College at Pia in 1980, he worked on Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s The Man Who Stole the Sun (1979) and Sômai Shinji’s Sailor Uniforms and Machine Guns (1981). Kurosawa was invited to join the Directors Company, an alternative to the major studios that offered creative freedom to young directors such as Hasegawa and Sômai. Under their auspices, he made his feature film debut with the pink film, The Kandagawa Wars, in 1983. Kurosawa next attempted to work directly for a major studio by directing a Nikkatsu Roman Porno entitled Seminar of Shyness, but the studio rejected the film, claiming that it lacked the requisite love interest. The film was eventually purchased from Nikkatsu and released as The Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl in 1985, but the incident gave him a reputation as an idiosyncratic character and made securing funding for other studio projects difficult. -

Bryan Kneale Bryan Kneale Ra

BRYAN KNEALE BRYAN KNEALE RA Foreword by Brian Catling and essays by Andrew Lambirth, Jon Wood and Judith LeGrove PANGOLIN LONDON CONTENTS FOREWORD Another Brimful of Grace by Brian Catling 7 CHAPTER 1 The Opening Years by Andrew Lambirth 23 CHAPTER 2 First published in 2018 by Pangolin London Pangolin London, 90 York Way, London N1 9AG Productive Tensions by Jon Wood 55 E: [email protected] www.pangolinlondon.com ISBN 978-0-9956213-8-1 CHAPTER 3 All rights reserved. Except for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, sorted in a Seeing Anew by Judith LeGrove 87 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Pangolin London © All rights reserved Set in Gill Sans Light BIOGRAPHY 130 Designed by Pangolin London Printed in the UK by Healeys Printers INDEX 134 (ABOVE) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 136 Bryan Kneale, c.1950s (INSIDE COVER) Bryan Kneale with Catalyst Catalyst 1964, Steel Unique Height: 215 cm 4 5 FOREWORD ANOTHER BRIMFUL OF GRACE “BOAYL NAGH VEL AGGLE CHA VEL GRAYSE” BY BRIAN CATLING Since the first draft of this enthusiasm for Bryan’s that is as telling as a storm and as monumental as work, which I had the privilege to write a couple a runic glyph. And makes yet another lens to look of years ago, a whole new wealth of paintings back on a lifetime of distinctively original work. have been made, and it is in their illumination that Notwithstanding, it would be irreverent I keep some of the core material about the life to discuss these works without acknowledging of Bryan Kneale’s extraordinary talent. -

Newsletter Template Summer.Qxd

The Ghost Club Founded 1862 Newsletter – Summer 2006 ISSUED TO MEMBERS ONLY Copyright: The Ghost Club. All rights reserved “Nasci, Laborare, Mori, Nasci” a member of the Ghost Club, a cultural his- torian and worked as Press Officer for the The Ghost National Trust for more than eight years, so had a real insight into the properties and their ghostly residents. Cover: VictorianC Cartel deu Posteb P4 The AGM saw Council Members give a brief account of their work during the last Chairman’s Letter . 2 year and the new roles of Newsletter Producer and Scientific Officer were for- A Victorian Classic . 4 mally endorsed by the membership. Photographing Ghosts . 5 Congratulations to Ian Johnson, who was elected as Science Officer, and to Sarah County Ghosts . .11 Darnell and Monica Tandy, who were for- mally elected as Newsletter Producer and Book Reviews. .12 Newsletter Editor respectively. The remaining Council were re-elected to serve Personal acounts . .20 another year. (Details of the Council Members, their positions and contact Ghosts in the News . 24 details can be found on the back page). I News from AGHOST. 28 would like to take this opportunity to thank the Council for all their hard work last year Meet the Council . 32 and am looking forward to serving another year with them all. Investigations . .35 The Council would like to thank every- body instrumental in organising and set- ting up investigations last year. In recog- nition of their hard work in 2005, the Council awarded the following Area CHAIRMAN’S LETTER Coordinators a year’s free membership: Derek Green Yves (Nobby) Clarke Carol Tolhurst Clarke n Saturday June 17th, members Steve Rose braved the heat and the crowds in Kellie Kirkman London who were attending the Thank you all very much, for your time OQueens Birthday celebrations, to attend the and effort.