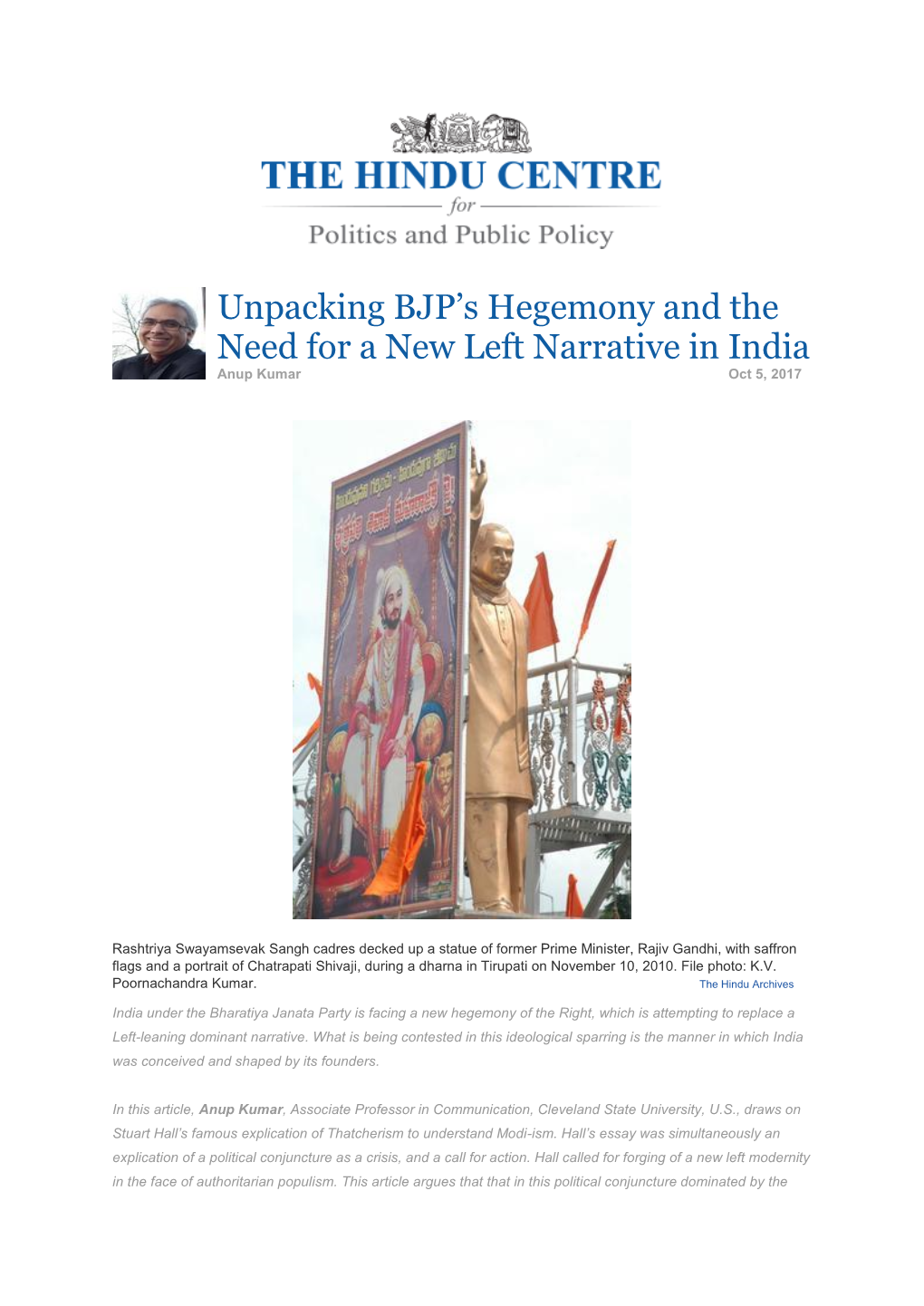

Unpacking BJP's Hegemony and the Need for a New Left Narrative in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal*

Feminist Dissent Hindutva Past and Present: From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal* *Correspondence: secularspaces@ gmail.com Abstract This essay outlines the beginnings of Hindutva, a political movement aimed at establishing rule by the Hindu majority. It describes the origin myths of Aryan supremacy that Hindutva has developed, alongside the campaign to build a temple on the supposed birthplace of Ram, as well as the re-writing of history. These characteristics suggest that it is a far-right fundamentalist movement, in accordance with the definition of fundamentalism proposed by Feminist Dissent. Finally, it outlines Hindutva’s ‘re-imagining’ of Peer review: This article secularism and its violent campaigns against those it labels as ‘outsiders’ has been subject to a double blind peer review to its constructed imaginary of India. process Keywords: Hindutva, fundamentalism, secularism © Copyright: The Hindutva, the fundamentalist political movement of Hinduism, is also a Authors. This article is issued under the terms of foundational movement of the 20th century far right. Unlike its European the Creative Commons Attribution Non- contemporaries in Italy, Spain and Germany, which emerged in the post- Commercial Share Alike License, which permits first World War period and rapidly ascended to power, Hindutva struggled use and redistribution of the work provided that to gain mass acceptance and was held off by mass democratic movements. the original author and source are credited, the The anti-colonial struggle as well as Left, rationalist and feminist work is not used for commercial purposes and movements recognised its dangers and mobilised against it. Their support that any derivative works for anti-fascism abroad and their struggles against British imperialism and are made available under the same license terms. -

HINDUTVA AS an INFORMAL INSTITUTION Abstract

International Journal of Economics, Politics, Humanities & Social Sciences Vol: 3 Issue: 4 e-ISSN: 2636-8137 Fall 2020 HINDUTVA AS AN INFORMAL INSTITUTION Hayati ÜNLÜ1 Makale İlk Gönderim Tarihi / Recieved (First): 30.05.2020 Makale Kabul Tarihi / Accepted: 10.10.2020 Abstract In this article, Hindu nationalism has been considered as an informal institution through an institutionalist perspective. The purpose of the article is to identify how Hindutva functions as an informal institution. In this context, Hindutva has been evaluated based on three basic features of an institution: setting rules, shaping behavior and effecting the result. The rule- making feature has been studied through the ideas of ideologists such as Savarkar and Golwalkar with reference to the Hindu social order. Subsequently, it has been argued that these socio-political rules have been accepted by the huge social segments in the country and influenced the behaviors of the social base. Finally, it has been emphasized how Hindutva has influenced the result and brought the Hindu nationalists to power. Accordingly, it will be concluded how Hindutva has become the mainstream of politics in the country. However, with reference to the recent Citizenship Law protests in the country, it has been noted how other informal institutions, particularly secularism, threaten the future of Hindutva. Keywords: Hindutva, Informal Institutions, Rules, Behaviors, Results. 1 Dr. Öğr. Üyesi, Şırnak Üniversitesi, İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, Siyaset Bilimi ve Kamu Yönetimi Bölümü, [email protected] , ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2645-5930 Vol: 3 Issue: 4 Hayati Ünlü Hindutva as an Informal Institution Fall 2020 1. Introduction The return of institutions has been discussed in global politics these days. -

Hindu Fundamentalism and Christian Response in India

HINDU FUNDAMENTALISM AND CHRISTIAN RESPONSE IN INDIA Rev. Shadakshari T.K. (Bangalore, India and Pastoring Divyajyothi Church of the Nazarene) Introduction One of the purposes of religion, humanly speaking, is to enable people to live a responsible life. One desire is that religious people may not disturb the harmonious life; rather, they may contribute towards it. Today, religions have become a source of conflict and violence in many Asian societies. This is very evident in India where the inter-relationship among religions is breaking up. The contemporary problem in India is the question of nationalism and the issue of marginalized identities. Christians are caught between two: participation in the nationalism in the one hand and commitment to the cause of the marginalized on the other. There is an awakening of nationalism, which bears strong religious stamp, which is strongly promoted by the Hindutva ideology. At the same time there is a strong awakening of the Tribals and Dalits. In this context, the question comes to our mind: how do Christians in India serve both nationalism and marginal groups when both of them are opposing each other? I am not promising the absolute answer for the question raised. However, this article provides some clues by analyzing the historical development of religious fundamentalism and suggesting an appropriate response for Christians. Though there are several religious fundamental groups in the history of India (including Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, and others), this article limits its study to the religious fundamentalism of Hinduism. The importance of Hindu fundamentalism lies in its very contemporary and nationalistic scope, compared to other, more regional expressions. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage As Violation of Human Rights

Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage as Violation of Human Rights Case of India: a small Note Ram Puniyani India is a country with rich diversity. It has immense cultural heritage which came as a synthesis, blending and independent existence of different cultures which interacted and lived together harmoniously for centuries. It is a place where the people of all religions have been frequenting the places of worship of other religions. We have Bhakti (devotional) stream which is revered by people of all religions, it has Sufi saint shrines where people of different religions rub shoulders with each other in paying respect to the humanistic Sufi saints. There are places like Shabriamala in Kerala, where the Hindu devotees throng. On their way to their favorite deity they also visit a mosque and a Church. We have Mother Velinkini shrine where again people of diverse faith come and pay their respect. Such places abound all over the country, well revered and respected by one and all. Last few decades there is a lot of problem in such traditions of the country. The identity based politics of Hindutva has targeted the religious minorities particularly Muslims and Christians. Hindutva is not religion, it is a politics based on the dominant tendency within Hinduism, i.e. Brahmanism. Due to the overwhelming domination of Hindutva politics in cultural matters, in matters related to places of worship, and the ones related to food habits, the traditions are being violated on political ground. The major victims of this are not only religious minorities, but even the indigenous people, Adivasis, and other downtrodden sections of society. -

Radical Islam and Democracy

RADICAL ISLAM & DEMOCRACY INDIAN AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN EXPERIENCES CONFERENCE REPORT Edited by Maj Gen Dipankar Banerjee D. Suba chandran Sonali HURIA Organized by IPCS & KAS RADICAL ISLAM & DEMOCRACY Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) German House, 1st Floor, 2, Nyaya Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 11 00 21 INDIA Tel: 91-11- 26113520 , 24104008; Fax: 91-11- 26113536 The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung is one of the Institute of Peace and Conflict political foundations of the Federal Republic Studies (IPCS) of Germany. With its activities and projects, B 7/3 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi 110029 IN- the Foundation realizes an active and substan- DIA tial contribution to international cooperation and understanding. Phone: (91-11) 41652556-59; Fax: (91-11) 41652560 The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung has organized its program priorities in India into five working The Institute was established in August 1996 as areas: Social Changes, Civil Society, Political an independent think tank devoted to studying Parties, Rule of Law; Economic Reforms, security issues relating to South Asia. Over the Small Medium Enterprises; Bilateral Relations, years leading strategic thinkers, academicians, International Relations, Security Policy; Pov- former members of the Civil Services, Foreign erty Alleviation, Integrated Rural Develop- Services, Armed Forces, Police Forces, Para- ment, Panchayati Raj Institutions; and Media, military Forces and media persons (print and Public Relations. In implementing its project electronic) have been associated with the Insti- and programs, the Foundation cooperates with tute in its endeavour to chalk out a comprehen- Indian partner organisations, such as think sive framework for security studies - one which tanks, government and non-governmental in- can cater to the changing demands of national, stitutions. -

Behavioural Thatcherism and Nostalgia: Tracing the Everyday Consequences of Holding Thatcherite Values

This is a repository copy of Behavioural Thatcherism and nostalgia: tracing the everyday consequences of holding Thatcherite values. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/156333/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Farrall, S., Hay, C. orcid.org/0000-0001-6327-6547, Gray, E. et al. (1 more author) (2020) Behavioural Thatcherism and nostalgia: tracing the everyday consequences of holding Thatcherite values. British Politics. ISSN 1746-918X https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-019-00130-7 This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in British Politics. The final authenticated version is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41293-019- 00130-7. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ___________________________________________________________________ Behavioural Thatcherism And Nostalgia: Tracing the Behavioural Consequences of holding Thatcherite Values _______________________________________________ Stephen Farrall*ᵻ, Colin Hay**, Emily Gray* and Phil Jones* *Department of Criminology, College of Business, Law and the Social Sciences, University of Derby, UK; ** Centre d’Études Européennes, CNRS, Sciences Po, Paris, France and SPERI, University of Sheffield, UK. -

Class Struggle and Education: Neoliberalism, (Neo)-Conservatism, and the Capitalist Assault on Public Education’, Critical Education

South Asian University, Delhi, 22-23 March 2014 Transformative Education, Critical Education, Marxist Education: Possibilities and Alternatives to the Restructuring of Education in Global Neoliberal / Neoconservative Times Dave Hill Research Professor of Education at Anglia Ruskin University Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education Anglia Ruskin University Chelmsford Campus Bishop Hall Lane Chelmsford, CM11SQ, England Work Phone: +44 845271333 Home Phone: +441273270943 Mobile Phone: +44 7973194357 TOTAL WORD COUNT: 6,742 words Transformative Education, Critical Education, Marxist Education: Possibilities and Alternatives to the Restructuring of Education in Global Neoliberal / Neoconservative Times Abstract This paper briefly examines the context-specific paths and policies of neoliberalism and neoconservatism and the resistance to their depradations. While calling for activism with micro-, meso- and macro-social and political arenas, the paper focuses on activity within formal education institutions. It suggests a series of measures- a socialist Manifesto for education, for discussion. It concludes with a call to action for teachers and education workers (and others) to be “Critical Educators,” Resistors, Marxist activists, within and outside official education. Neoliberalism and (Neo)-conservatism and The Nature and Power of the Resistance The paths of neoliberalisation and (neo)-conservatism are similar in many countries. But each country has its own history, has its own particular context; each country has its own balance of class forces, its own level of organization of the working class and the capitalist class, and different levels of confidence within the working class and within the capitalist class. In countries where resistance to neoliberalism is very strong, as in Greece, then the government has found it actually so far very difficult to engage in large-scale privatization. -

Margaret Thatcher, Thatcherism and Education

Commentary Reginald Edwards McGill University Margaret Thatcher, Thatcherism and Education The changes in educational policy in Britain that are being promoted by Margaret Thatcher's government are of such significance that educators in North America might be well advised to take notice of them. Professor Buck, in the Win ter issue of this journal, detailed many of these changes and compared them to the policies of Matthew Arnold. In this commentary, an attempt is made to examine the personal and political background of Margaret Thatcher and to draw sorne inferences about the origin of her ideas and policies, which have come to be known commonlyas "Thatcherism." Thatcher's personal background Margaret Roberts, born in Grantham, Lincolnshire, in 1925, began her education in a local primary school, and at the age of eleven began secondary education at the Kestevan and Grantham Grammar School for Girls. Admitted to Somerville College, Oxford, in 1943, she graduated in Science in 1946. In her final year she was the President of the Oxford University Conservative Association and, in this capacity, was invited to her first Annual Conference of the Conservative Party in 1946. She attended her second conference in 1948, as the representative of the Graduates' Association, and met representatives of the Dartford constituency. Asking to submit her name as a candidate for nomination, she was accepted, and she contested, unsuccessfully, the elections of 1950 and 1951 for that constituency. Through her political activities she met Dennis Thatcher, whom she married in an East London Methodist Chapel in December 1951. After marriage she began to study law, specializing in taxation law, and was adJTJitted to the Bar in 1954, one year after giving birth to twins. -

Behavioural Thatcherism and Nostalgia: Tracing the Everyday Consequences of Holding Thatcherite Values

Behavioural thatcherism and nostalgia: tracing the everyday consequences of holding thatcherite values Item Type Article Authors Farrall, Stephen; Gray, Emily; Jones, Phillip Mike; Hay, Colin Citation Farrall, S., Hay, C., Gray, E. and Jones, P. J., (2020). 'Behavioural Thatcherism and nostalgia: tracing the everyday consequences of holding Thatcherite Values'. British Politics, pp. 1-21. DOI: 10.1057/s41293-019-00130-7. DOI 10.1057/s41293-019-00130-7 Publisher Palgrave Journal British Politics Download date 26/09/2021 13:26:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/624431 ___________________________________________________________________ Behavioural Thatcherism And Nostalgia: Tracing the Everyday Consequences of holding Thatcherite Values _______________________________________________ Stephen Farrall*ᵻ, Colin Hay**, Emily Gray* and Phil Mike Jones* *Department of Criminology, College of Business, Law and the Social Sciences, University of Derby, UK; ** Centre d’Études Européennes, CNRS, Sciences Po, Paris, France and SPERI, University of Sheffield, UK. ᵻ Corresponding author ([email protected]). Abstract With the passing of time and the benefit of hindsight there is, again, growing interest in Thatcherism – above all in its substantive and enduring legacy. But, to date at least, and largely due to data limitations, little of that work has focussed on tracing the behavioural consequences, at the individual level, of holding Thatcherite values. That oversight we seek both to identify more clearly and to begin to address. Deploying new survey data, we use multiple linear regression and structural equation modelling to unpack the relationship between ‘attitudinal’ and ‘behavioural’ Thatcherism. In the process we reveal the considerably greater behavioural consequences of holding neo-liberal, as distinct from neo-conservative, values whilst identifying the key mediating role played by social, political and economic nostalgia. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

The State, Society and Markets in Hindu Nationalism Modern Asian Studies, 2018; Online Publ:1-34

ACCEPTED VERSION Priya Chacko Marketising Hindutva: The state, society and markets in Hindu Nationalism Modern Asian Studies, 2018; Online Publ:1-34 © CambridgeUniversity Press 2018 Originally Published at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X17000051 PERMISSIONS https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/open-access-policies/open-access-journals/green-open- access-policy-for-journals Green OA applies to all our journal articles, but it is primarily designed to support OA for articles that are otherwise only available by subscription or other payment. For that reason, we are more restrictive in what we allow under Green OA in comparison with Gold OA: The final, published version of the article cannot be made Green OA (see below). The Green OA version of the article is made available to readers for private research and study only (see also Information for repositories, below). We do not allow Green OA articles to be made available under Creative Commons licences. Funder policies vary in which version of an article can be made Green OA. We use the following definitions (adapted from the National Information Standards Organization – NISO): Exceptions Some of our journals do not follow our standard Green archiving policy. Please check the relevant journal's individual policy here. 21 January 2019 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/117274 7 June 2016 Marketising Hindutva: The state, society and markets in Hindu Nationalism Priya Chacko Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Adelaide, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract The embrace of markets and globalisation by radical political parties is often taken as reflecting and facilitating the moderation of their ideologies.