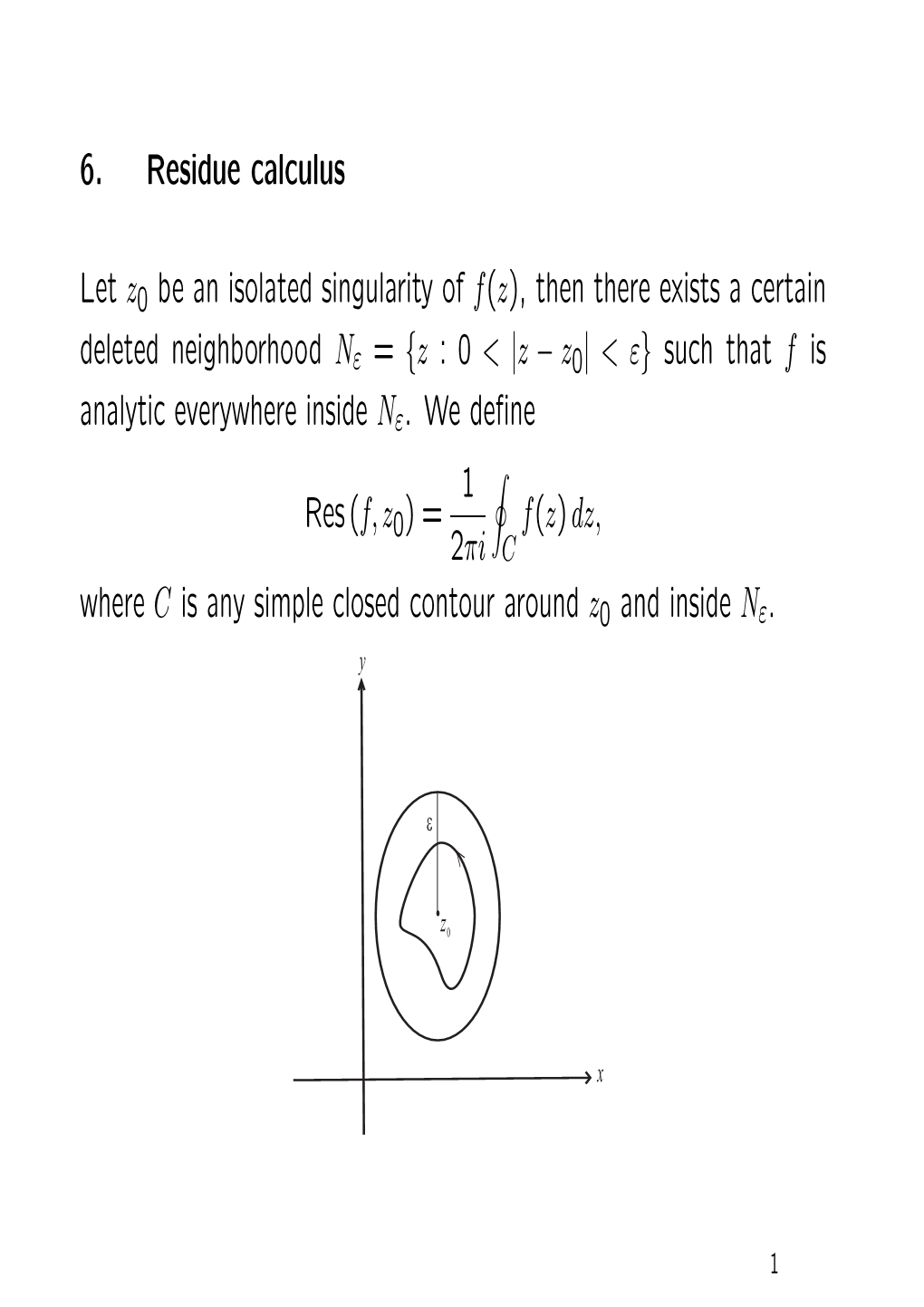

6. Residue Calculus Let Z0be an Isolated Singularity of F(Z)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Subanalytic Cmc Surfaces

GLOBALLY SUBANALYTIC CMC SURFACES IN R3 WITH SINGULARITIES JOSE´ EDSON SAMPAIO Abstract. In this paper we present a classification of a class of globally sub- 3 analytic CMC surfaces in R that generalizes the recent classification made by Barbosa and do Carmo in 2016. We show that a globally subanalytic CMC 3 surface in R with isolated singularities and a suitable condition of local con- nectedness is a plane or a finite union of round spheres and right circular cylinders touching at the singularities. As a consequence, we obtain that a 3 globally subanalytic CMC surface in R that is a topological manifold does not have isolated singularities. It is also proved that a connected closed glob- 3 ally subanalytic CMC surface in R with isolated singularities which is locally Lipschitz normally embedded needs to be a plane or a round sphere or a right circular cylinder. A result in the case of non-isolated singularities is also pre- sented. It is also presented some results on regularity of semialgebraic sets and, in particular, it is proved a real version of Mumford's Theorem on regu- larity of normal complex analytic surfaces and a result about C1 regularity of minimal varieties. 1. Introduction The question of describing minimal surfaces or, more generally, surfaces of con- stant mean curvature (CMC surfaces) is known in Analysis and Differential Geom- etry since the classical papers of Bernstein [4], Bombieri, De Giorgi and Giusti [9], Hopf [26] and Alexandrov [1]. Recently, in the paper [2], Barbosa and do Carmo showed that the connected algebraic smooth CMC surfaces in R3 are only the planes, round spheres and right circular cylinders. -

Topic 7 Notes 7 Taylor and Laurent Series

Topic 7 Notes Jeremy Orloff 7 Taylor and Laurent series 7.1 Introduction We originally defined an analytic function as one where the derivative, defined as a limit of ratios, existed. We went on to prove Cauchy's theorem and Cauchy's integral formula. These revealed some deep properties of analytic functions, e.g. the existence of derivatives of all orders. Our goal in this topic is to express analytic functions as infinite power series. This will lead us to Taylor series. When a complex function has an isolated singularity at a point we will replace Taylor series by Laurent series. Not surprisingly we will derive these series from Cauchy's integral formula. Although we come to power series representations after exploring other properties of analytic functions, they will be one of our main tools in understanding and computing with analytic functions. 7.2 Geometric series Having a detailed understanding of geometric series will enable us to use Cauchy's integral formula to understand power series representations of analytic functions. We start with the definition: Definition. A finite geometric series has one of the following (all equivalent) forms. 2 3 n Sn = a(1 + r + r + r + ::: + r ) = a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ::: + arn n X = arj j=0 n X = a rj j=0 The number r is called the ratio of the geometric series because it is the ratio of consecutive terms of the series. Theorem. The sum of a finite geometric series is given by a(1 − rn+1) S = a(1 + r + r2 + r3 + ::: + rn) = : (1) n 1 − r Proof. -

Complex Analysis Class 24: Wednesday April 2

Complex Analysis Math 214 Spring 2014 Fowler 307 MWF 3:00pm - 3:55pm c 2014 Ron Buckmire http://faculty.oxy.edu/ron/math/312/14/ Class 24: Wednesday April 2 TITLE Classifying Singularities using Laurent Series CURRENT READING Zill & Shanahan, §6.2-6.3 HOMEWORK Zill & Shanahan, §6.2 3, 15, 20, 24 33*. §6.3 7, 8, 9, 10. SUMMARY We shall be introduced to Laurent Series and learn how to use them to classify different various kinds of singularities (locations where complex functions are no longer analytic). Classifying Singularities There are basically three types of singularities (points where f(z) is not analytic) in the complex plane. Isolated Singularity An isolated singularity of a function f(z) is a point z0 such that f(z) is analytic on the punctured disc 0 < |z − z0| <rbut is undefined at z = z0. We usually call isolated singularities poles. An example is z = i for the function z/(z − i). Removable Singularity A removable singularity is a point z0 where the function f(z0) appears to be undefined but if we assign f(z0) the value w0 with the knowledge that lim f(z)=w0 then we can say that we z→z0 have “removed” the singularity. An example would be the point z = 0 for f(z) = sin(z)/z. Branch Singularity A branch singularity is a point z0 through which all possible branch cuts of a multi-valued function can be drawn to produce a single-valued function. An example of such a point would be the point z = 0 for Log (z). -

Residue Theorem

Topic 8 Notes Jeremy Orloff 8 Residue Theorem 8.1 Poles and zeros f z z We remind you of the following terminology: Suppose . / is analytic at 0 and f z a z z n a z z n+1 ; . / = n. * 0/ + n+1. * 0/ + § a ≠ f n z n z with n 0. Then we say has a zero of order at 0. If = 1 we say 0 is a simple zero. f z Suppose has an isolated singularity at 0 and Laurent series b b b n n*1 1 f .z/ = + + § + + a + a .z * z / + § z z n z z n*1 z z 0 1 0 . * 0/ . * 0/ * 0 < z z < R b ≠ f n z which converges on 0 * 0 and with n 0. Then we say has a pole of order at 0. n z If = 1 we say 0 is a simple pole. There are several examples in the Topic 7 notes. Here is one more Example 8.1. z + 1 f .z/ = z3.z2 + 1/ has isolated singularities at z = 0; ,i and a zero at z = *1. We will show that z = 0 is a pole of order 3, z = ,i are poles of order 1 and z = *1 is a zero of order 1. The style of argument is the same in each case. At z = 0: 1 z + 1 f .z/ = ⋅ : z3 z2 + 1 Call the second factor g.z/. Since g.z/ is analytic at z = 0 and g.0/ = 1, it has a Taylor series z + 1 g.z/ = = 1 + a z + a z2 + § z2 + 1 1 2 Therefore 1 a a f .z/ = + 1 +2 + § : z3 z2 z This shows z = 0 is a pole of order 3. -

Chapter 2 Complex Analysis

Chapter 2 Complex Analysis In this part of the course we will study some basic complex analysis. This is an extremely useful and beautiful part of mathematics and forms the basis of many techniques employed in many branches of mathematics and physics. We will extend the notions of derivatives and integrals, familiar from calculus, to the case of complex functions of a complex variable. In so doing we will come across analytic functions, which form the centerpiece of this part of the course. In fact, to a large extent complex analysis is the study of analytic functions. After a brief review of complex numbers as points in the complex plane, we will ¯rst discuss analyticity and give plenty of examples of analytic functions. We will then discuss complex integration, culminating with the generalised Cauchy Integral Formula, and some of its applications. We then go on to discuss the power series representations of analytic functions and the residue calculus, which will allow us to compute many real integrals and in¯nite sums very easily via complex integration. 2.1 Analytic functions In this section we will study complex functions of a complex variable. We will see that di®erentiability of such a function is a non-trivial property, giving rise to the concept of an analytic function. We will then study many examples of analytic functions. In fact, the construction of analytic functions will form a basic leitmotif for this part of the course. 2.1.1 The complex plane We already discussed complex numbers briefly in Section 1.3.5. -

Laurent Series and Residue Calculus

Laurent Series and Residue Calculus Nikhil Srivastava March 19, 2015 If f is analytic at z0, then it may be written as a power series: 2 f(z) = a0 + a1(z − z0) + a2(z − z0) + ::: which converges in an open disk around z0. In fact, this power series is simply the Taylor series of f at z0, and its coefficients are given by I 1 (n) 1 f(z) an = f (z0) = n+1 ; n! 2πi (z − z0) where the latter equality comes from Cauchy's integral formula, and the integral is over a positively oriented contour containing z0 contained in the disk where it f(z) is analytic. The existence of this power series is an extremely useful characterization of f near z0, and from it many other useful properties may be deduced (such as the existence of infinitely many derivatives, vanishing of simple closed contour integrals around z0 contained in the disk of convergence, and many more). The situation is not much worse when z0 is an isolated singularity of f, i.e., f(z) is analytic in a puncured disk 0 < jz − z0j < r for some r. In this case, we have: Laurent's Theorem. If z0 is an isolated singularity of f and f(z) is analytic in the annulus 0 < jz − z0j < r, then 2 b1 b2 bn f(z) = a0 + a1(z − z0) + a2(z − z0) + ::: + + 2 + ::: + n + :::; (∗) z − z0 (z − z0) (z − z0) where the series converges absolutely in the annulus. In class I described how this can be done for any annulus, but the most useful case is a punctured disk around an isolated singularity. -

Lecture #31: the Cauchy Residue Theorem

Mathematics312(Fall2013) November25,2013 Prof. Michael Kozdron Lecture #31: The Cauchy Residue Theorem Recall that last class we showed that a function f(z)hasapoleoforderm at z0 if and only if g(z) f(z)= (z z )m − 0 for some function g(z)thatisanalyticinaneighbourhoodofz and has g(z ) =0.Wealso 0 0 derived a formula for Res(f; z0). Theorem 31.1. If f(z) is analytic for 0 < z z0 <Rand has a pole of order m at z0, then | − | m 1 m 1 1 d − m 1 d − m Res(f; z0)= m 1 (z z0) f(z) = lim m 1 (z z0) f(z). (m 1)! dz − − (m 1)! z z0 dz − − z=z0 → − − In particular, if z0 is a simple pole, then Res(f; z0)=(z z0)f(z) =lim(z z0)f(z). − z z0 − z=z0 → Example 31.2. Suppose that sin z f(z)= . (z2 1)2 − Determine the order of the pole at z0 =1. Solution. Observe that z2 1=(z 1)(z +1)andso − − sin z sin z sin z/(z +1)2 f(z)= = = . (z2 1)2 (z 1)2(z +1)2 (z 1)2 − − − Since sin z g(z)= (z +1)2 2 is analytic at 1 and g(1) = 2− sin(1) =0,weconcludethatz =1isapoleoforder2. 0 Example 31.3. Determine the residue at z0 =1of sin z f(z)= (z2 1)2 − and compute f(z)dz C where C = z 1 =1/2 is the circle of radius 1/2centredat1orientedcounterclockwise. {| − | } 31–1 Solution. Since we can write (z 1)2f(z)=g(z)where − sin z g(z)= (z +1)2 is analytic at z =1withg(1) =0,theresidueoff(z)atz =1is 0 0 1 d2 1 d Res(f;1)= − (z 1)2f(z) = (z 1)2f(z) (2 1)! dz2 1 − dz − − − z=1 z=1 d sin z = dz (z +1)2 z=1 (z +1)2 cosz 2(z +1)sinz = − (z +1)4 z=1 4cos1 4sin1 = − 16 cos 1 sin 1 = − . -

Complex Analysis in a Nutshell

Complex analysis in a nutshell. Definition. A function f of one complex variable is said to be differentiable at z0 2 C if the limit f(z) − f(z ) lim 0 z z0 ! z − z0 exists and does not depend on the manner in which the variable z 2 C approaches z0. Cauchy-Riemann equations. A function f(z) = f(x; y) = u(x; y) + iv(x; y) (with u and v the real and the imaginary parts of f respectively) is differentiable at z0 = x0 + iy0 if and only if it satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations @u @v @u @v = ; = − at (x ; y ): @x @v @y @x 0 0 Definition. A function f is analytic at z0 if it is differentiable in a neighborhood of z0. Harmonic functions. Let D be a region in IR2 identified with C. A function u : D ! IR is the real (or imaginary) part of an analytic function if and only if it is harmonic, i.e., if it satisfies @2u @2u + = 0: @x2 @y2 Cauchy formulas. Let a function f be analytic in an open simply connected region D, let Γ be a simple closed curve contained entirely in D and traversed once counterclockwise, and let z0 lie inside Γ. Then f(z) dz = 0; IΓ f(z) dz = 2πif(z0); IΓ z − z0 f(z) dz 2πi (n) n+1 = f (z0); n 2 IN: IΓ (z − z0) n! Definition. A function analytic in C is called entire. Zeros and poles. If a function f analytic in a neighborhood of a point z0, vanishes at z0, k and is not identically zero, then f(z) = (z − z0) g(z) where k 2 IN, g is another function analytic in a neighborhood of z0, and g(z0) =6 0. -

Applied Picard–Lefschetz Theory

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/surv/097 Applied Picard-Lefschetz Theory Mathematical Surveys and Monographs Volume 97 Applied Picard-Lefschetz Theory V. A. Vassiliev AVAEM^ American Mathematical Society Editorial Board Peter S. Landweber Tudor Stefan Ratiu Michael P. Loss, Chair J. T. Stafford 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 14D05, 14B05, 31B10, 32S40, 35B60; Secondary 33C70, 35L67. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vasil'ev, V. A., 1956- Applied Picard-Lefschetz theory / V. A. Vassiliev. p. cm. — (Mathematical surveys and monographs, ISSN 0076-5376 ; v. 97) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8218-2948-3 (alk. paper) 1. Picard-Lefschetz theory. 2. Singularities (Mathematics) 3. Integral representations. I. Title. II. Mathematical surveys and monographs ; no. 97. QA564.V37 2002 516.3'5—dc21 2002066541 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. Requests for such permission should be addressed to the Acquisitions Department, American Mathematical Society, 201 Charles Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02904-2294, USA. Requests can also be made by e-mail to [email protected]. © 2002 by the American Mathematical Society. All rights reserved. The American Mathematical Society retains all rights except those granted to the United States Government. -

20. Isolated Singularities Definition 20.1. Let F : U −→ C Be A

20. Isolated Singularities Definition 20.1. Let f : U −! C be a holomorphic function on a region U. Let a2 = U. We say that a is an isolated singularity of f if U contains a punctured neighbourhood of a. Note that Log z does not have an isolated singularity at 0, since we have to remove all of (−∞; 0] to get a continuous function. By contrast its derivative 1=z is holomorphic except at 0 and so it has an isolated singularity at 0. Suppose that f has an isolated singularity at a. As a punctured neighbourhood of a is a special type of annulus, f has a Laurent ex- pansion centred at a, 1 X k f(z) = ak(z − a) ; k=−∞ valid for 0 < jz − aj < r; for some real r. The behaviour at a is dictated by the negative part of the Laurent expansion. Definition 20.2. If f has an isolated singularity at a and all of the coefficients ak of the Laurent expansion 1 X k f(z) = ak(z − a) ; k=−∞ vanish if k < 0, then we say that f has a removable singularity. If f has a removable singularity then in fact we can extend f to a holomorphic function in a neighbourhood of a. Indeed, the Laurent ex- pansion of f is a power series expansion, and this defines a holomorphic function in a neighbourhood of a. Example 20.3. The function sin z z has a removable singularity at a. 1 Indeed, sin z 1 z3 z3 = z − + + ::: z z 3! 5! z2 z4 = 1 − + + :::; 3! 5! is the Laurent series expansion of sin z=z. -

Chapter 4 Complex Analysis

Chapter 4 Complex Analysis 4.1 Complex Differentiation Recall the definition of differentiation for a real function f(x): f(x + δx) − f(x) f 0(x) = lim . δx→0 δx In this definition, it is important that the limit is the same whichever direction we approach from. Consider |x| at x = 0 for example; if we approach from the right (δx → 0+) then the limit is +1, whereas if we approach from the left (δx → 0−) the limit is −1. Because these limits are different, we say that |x| is not differentiable at x = 0. Now extend the definition to complex functions f(z): f(z + δz) − f(z) f 0(z) = lim . δz→0 δz Again, the limit must be the same whichever direction we approach from; but now there is an infinity of possible directions. Definition: if f 0(z) exists and is continuous in some region R of the complex plane, we say that f is analytic in R. If f(z) is analytic in some small region around a point z0, then we say that f(z) is analytic at z0. The term regular is also used instead of analytic. Note: the property of analyticity is in fact a surprisingly strong one! For example, two consequences include: (i) If a function is analytic then it is differentiable infinitely many times. (Cf. the existence of real functions which can be differentiated N times but no more, for any given N.) 64 © R. E. Hunt, 2002 (ii) If a function is analytic and bounded in the whole complex plane, then it is constant. -

Summary of Results from Chapter 4: Complex Analysis

Summary of Results from Chapter 4: Complex Analysis Analyticity A function f(z) is differentiable at z if the limit f(z + δz) − f(z) f 0(z) = lim δz→0 δz exists and is independent of the direction taken by δz in the limiting process. A function f(z) is analytic (or regular) in a region R ⊆ C if f 0(z) exists and is continuous for all z ∈ R. It is analytic at a point z0 if it is analytic in some neighbourhood of z0, i.e., in some region enclosing z0. f(z) is differentiable at z0 if and only if the Cauchy–Riemann equations ∂u ∂v ∂u ∂v = , = − ∂x ∂y ∂y ∂x hold at z0, where u(x, y) = Re f(x + iy) and v(x, y) = Im f(x + iy). The functions u and v are harmonic, i.e., satisfy Laplace’s equation in two dimensions. Laurent Expansions If f(z) is analytic in some annulus centred at z0 then there exist complex constants an such that ∞ X n f(z) = an(z − z0) n=−∞ within the annulus. An isolated singularity of a function f(z) is a point z0 at which f is singular, but where otherwise f is analytic within some neighbourhood of z0. A Laurent expansion of f always exists about an isolated singularity. If there are non-zero an for arbitrarily large negative n then f has an essential isolated singularity at z0. If an = 0 for all n < −N, but a−N 6= 0, where N is a positive integer, then f has a pole of order N at z0.