Sinclair Comment 11.2 DG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Structure and Media Diversity Scott J. Savage, Donald M

Market Structure and Media Diversity1 Scott J. Savage, Donald M. Waldman, Scott Hiller University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Economics Campus Box 256 Boulder, CO 80309-0256 Abstract We estimate the demand for local news service described by the offerings from newspapers, radio, television, the Internet, and Smartphone. The results show that the representative consumer values diversity in the reporting of news, more coverage of multicultural issues, and more information on community news. About two-thirds of consumers have a distaste for advertising, which likely reflects their consumption of general, all-purpose advertising delivered by traditional media. Demand estimates are used to calculate the impact on consumer welfare from a marginal decrease in the number of independent television stations that lowers the amount of diversity, multiculturalism, community news, and advertising in the market. Welfare decreases, but the losses are smaller in large markets. For example, small-market consumers lose $53 million annually while large-market consumers lose $15 million. If the change in market structure occurs in all markets, total losses nationwide would be about $830 million. September 25, 2012 Key words: market structure, media diversity, mixed logit, news, welfare JEL Classification Number: C9, C25, L13, L82, L96 1 The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Time Warner Cable (TWC) Research Program on Digital Communications provided funding for this research. We are grateful to Jessica Almond, Fernando Laguarda, Jonathan Levy, and Tracy Waldon for their assistance during the completion of this project. Yongmin Chen, Nicholas Flores, Jin-Hyuk Kim, David Layton, Edward Morey, Gregory Rosston, Bradley Wimmer, and seminar participants at the University of California, University of Colorado, SUNY and attendees at the Conference in Honor of Professor Emeritus Lester D. -

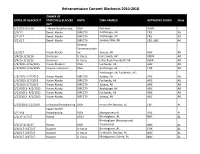

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Minority Views

MINORITY VIEWS The Minority Members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence on March 26, 2018 submit the following Minority Views to the Majority-produced "Repo11 on Russian Active Measures, March 22, 2018." Devin Nunes, California, CMAtRMAN K. Mich.J OI Conaw ay, Toxas Pe1 or T. King. New York F,ank A. LoBiondo, N ew Jersey Thom.is J. Roonev. Florida UNCLASSIFIED Ileana ROS·l chtinon, Florida HVC- 304, THE CAPITOL Michnel R. Turner, Ohio Brad R. Wons1 rup. Ohio U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES WASHINGTON, DC 20515 Ou is S1cwart. U1ah (202) 225-4121 Rick Cr.,w ford, Arka nsas P ERMANENT SELECT C OMMITTEE Trey Gowdy, South Carolina 0A~lON NELSON Ellsr. M . S1nfn11ik, Nnw York ON INTELLIGENCE SrAFf. D IREC f()ti Wi ll Hurd, Tcxa~ T11\'10l !IV s. 8 £.R(.REE N At1am 8 . Schiff, Cohforn1a , M tNORllV STAFF OtR ECToq RANKIN G M EMtlER Jorncs A. Himes, Connec1icut Terri A. Sewell, AlabJma AndrC Carso n, lncli.1 na Jacki e Speier, Callfomia Mike Quigley, Il linois E,ic Swalwell, California Joilq u1 0 Castro, T exas De nny Huck, Wash ington P::iul D . Ry an, SPCAl([ R or TH( HOUSE Noncv r c1os1. DEMOC 11t.1 1c Lr:.11.orn March 26, 2018 MINORITY VIEWS On March I, 201 7, the House Permanent Select Commiltee on Intelligence (HPSCI) approved a bipartisan "'Scope of In vestigation" to guide the Committee's inquiry into Russia 's interference in the 201 6 U.S. e lection.1 In announc ing these paramete rs for the House of Representatives' onl y authorized investigation into Russia's meddling, the Committee' s leadership pl edged to unde1take a thorough, bipartisan, and independent probe. -

PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-12-2012 PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation John, Tamara Cherisse, "PBS and the Young Adult Viewer" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 218. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/218 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER by Tamara John B.A., Radio-Television, Southern Illinois University, 2010 B.A., Spanish, Southern Illinois University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER By Tamara John A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Professional Media and Media Management Approved by: Dr. Paul Torre, Chair Dr. Beverly Love Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale March 28, 2012 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Tamara John, for the Master of Science degree in Professional Media and Media Management, presented on March 28, 2012, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Paul Torre Attracting and retaining teenage and young adult viewers has been a major challenge for most broadcasters. -

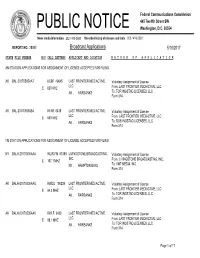

Broadcast Applications 5/10/2017

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28982 Broadcast Applications 5/10/2017 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING AK BAL-20170505AAT KCBF 49645 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 820 KHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 AK BAL-20170505ABA KFAR 6438 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 660 KHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: ROB INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NY BALH-20170505AAA WLIR-FM 61089 LIVINGSTONE BROADCASTING, Voluntary Assignment of License INC. E 107.1 MHZ From: LIVINGSTONE BROADCASTING, INC, NY , HAMPTON BAYS To: VMT MEDIA, INC. Form 314 AK BALH-20170505AAU KWDD 190239 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 94.3 MHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 AK BALH-20170505AAV KWLF 6439 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 98.1 MHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 17 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

Economic Development Strategy and Implemenation

MEDIA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION PLAN October 31, 2017 REPORT SUBMITTED TO: Jeff Smith, Borough Manager Media Borough 301 N. Jackson Street Media, PA 19063 REPORT SUBMITTED BY: Econsult Solutions, Inc. 1435 Walnut Street, 4th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19102 Econsult Solutions, Inc.| 1435 Walnut Street, 4th floor| Philadelphia, PA 19102 | 215-717-2777 | econsultsolutions.com Media, Pennsylvania | Economic Development Strategy and Implementation Plan | i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Our Charge and Our Approach ................................................................................ 1 1.2 Overview of the Report ............................................................................................... 2 2.0 Economic Vision and Goals ................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Vision Overview ............................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Public Outreach Methodology .................................................................................. 4 2.3 Summary of Public Outreach Findings ...................................................................... 4 2.4 Principles for the Economic Development Vision and Goals ................................ 5 2.5 Vision Statement ......................................................................................................... -

2019 Annual Report

A TEAM 2019 ANNU AL RE P ORT Letter to our Shareholders Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Dear Fellow Shareholders, BOARD OF DIRECTORS CORPORATE OFFICERS ANNUAL MEETING David D. Smith David D. Smith The Annual Meeting of stockholders When I wrote you last year, I expressed my sincere optimism for the future of our Company as we sought to redefine the role of a Chairman of the Board, Executive Chairman will be held at Sinclair Broadcast broadcaster in the 21st Century. Thanks to a number of strategic acquisitions and initiatives, we have achieved even greater success Executive Chairman Group’s corporate offices, in 2019 and transitioned to a more diversified media company. Our Company has never been in a better position to continue to Frederick G. Smith 10706 Beaver Dam Road grow and capitalize on an evolving media marketplace. Our achievements in 2019, not just for our bottom line, but also our strategic Frederick G. Smith Vice President Hunt Valley, MD 21030 positioning for the future, solidify our commitment to diversify and grow. As the new decade ushers in technology that continues to Vice President Thursday, June 4, 2020 at 10:00am. revolutionize how we experience live television, engage with consumers, and advance our content offerings, Sinclair is strategically J. Duncan Smith poised to capitalize on these inevitable changes. From our local news to our sports divisions, all supported by our dedicated and J. Duncan Smith Vice President INDEPENDENT REGISTERED PUBLIC innovative employees and executive leadership team, we have assembled not only a winning culture but ‘A Winning Team’ that will Vice President, Secretary ACCOUNTING FIRM serve us well for years to come. -

Report on New York City, NY Media Advertising Markets

Report on New York City, NY Media Advertising Markets Traditional Media Revenue Share and Concentration Analysis in Support of the Request For Waiver of Station WPIX Mark R. Fratrik, Ph. D. Vice President BIA Financial Network Introduction. This Report is submitted by Mark R. Fratrik, Ph. D., Vice President, BIA Financial Network. BIA Financial Network (BIAfn) is a financial and strategic consulting firm specializing in the media and communications industries. A copy of Dr. Fratrik’s vitae is attached at the end of this report, establishing his qualifications to collect and evaluate media advertising data, as well as the presence of media outlets in the New York DMA. On behalf of Station WPIX, New York City, New York (“WPIX”) and its parent, Tribune Company (“Tribune”), we are providing an analysis of the traditional media in the New York DMA with respect to the advertising revenue share and concentration of the New York media marketplace. We have looked specifically at the combination of WPIX and Newsday, a daily newspaper published in New York (“Newsday” together with WPIX, the “Tribune Properties”).1 In this Report, we compare estimated revenue shares of the Tribune Properties in the New York DMA with other media properties in the New York DMA. We also compare the revenue shares of the Tribune Properties in the New York DMA with the estimated revenue shares of the market revenue leaders in other top 10 DMAs in the United States2, and the average of the market revenue leaders in the nation as a whole. We also assess concentration in the New York DMA, and compare that level of concentration to the average of the top 10 DMAs, and the average concentration of all traditional media markets in the nation. -

2816 MACARTHUR ROAD WHITEHALL, PA La-Z-Boy TABLE of CONTENTS

2816 MACARTHUR ROAD WHITEHALL, PA La-Z-Boy TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Offering Summary Section 3: Location Overview Property Analysis.......................................................5 Area Demographics.................................................12 Lead Agents: Investment Overview & Highlights................................6 Economy and Travel.................................................13 Derrick Dougherty First Vice President Financing Details........................................................7 Economic Drivers.....................................................14 Philadelphia, PA Lease Abstract............................................................8 Regional Map..........................................................15 215.531.7026 [email protected] Competition Map.......................................................9 License: PA RS305854 Section 2: Tenant Overview Tenant Description....................................................10 Steven Garthwaite National Retail Group In The News............................................................11 Philadelphia, PA 215.531.7025 [email protected] NON-ENDORSEMENT PA RS332182 AND DISCLAIMER NOTICE NON-ENDORSEMENTS Scott Woodard Marcus & Millichap is not affiliated with, sponsored by, or endorsed by any commercial tenant or lessee identified in this marketing National Retail Group package. The presence of any corporation’s logo or name is not intended to indicate or imply affiliation with, or sponsorship or Philadelphia, -

September 28, 2017

1 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE EXECUTIVE SESSION PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WASHINGTON, D.C. INTERVIEW OF: BORIS EPSHTEYN Thursday, September 28, 2017 Washington, D.C. The interview in the above matter was held in Room HVC-304, the Capitol, commencing at 11:44 a.m. Present: Representatives Rooney, Schiff, Himes, Speier, Swalwell, and UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Castro. UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 3 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Appearances: For the PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE: For BORIS EPSHTEYN: CHRISTOPHER AMOLSCH UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 4 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Good morning. This is an unclassified, committee sensitive, transcribed interview of Boris Epshteyn. Thank you for speaking to us today. For the record, I am a staff member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. Others present today will introduce themselves when they speak. Before we begin, I have a security reminder. If you haven't left your electronics outside, please do at this time. I'm sure you've all left your electronics outside. MR. EPSHTEYN: Yes. That includes BlackBerrys, iPhones, Androids, tablets, iPads, or e-readers, laptop, iPods, MP3 players, recording devices, cameras, wireless headsets, pagers, and any other type of Bluetooth wristbands or watches. I also want to state a few things for the record. The questioning will be conducted by members and staff during their allotted time period. Some questions may seem basic, but that is because we need to clearly establish facts and understand the situation. -

Report on Chicago, IL Media Advertising Markets

Report on Chicago, IL Media Advertising Markets Traditional Media Revenue Share and Concentration Analysis in Support of the Request For Waiver of Stations WGN (TV) and WGN (AM) Mark R. Fratrik, Ph. D. Vice President BIA Financial Network Introduction. This Report is submitted by Mark R. Fratrik, Ph. D., Vice President, BIA Financial Network. BIA Financial Network (BIAfn) is a financial and strategic consulting firm specializing in the media and communications industries. A copy of Dr. Fratrik’s vitae is attached at the end of this report, establishing his qualifications to collect and evaluate media advertising data, as well as the presence of media outlets in the Chicago DMA. On behalf of WGN (TV), WGN (AM), the Chicago Tribune and its parent, Tribune Company (“Tribune”), we are providing an analysis of the traditional media in the Chicago DMA with respect to the advertising revenue share and concentration of the Chicago media marketplace. We have looked specifically at the combination of WGN (TV), WGN (AM), and the Chicago Tribune, a daily newspaper published in Chicago. In this Report, we compare estimated revenue shares of the Tribune Properties in the Chicago DMA with other media properties in the Chicago DMA. We also compare the revenue shares of the Tribune Properties in the Chicago DMA with the estimated revenue shares of the market revenue leaders in other top 10 DMAs in the United States,1 and the average of the market revenue leaders in the nation as a whole. We also assess concentration in the Chicago DMA, and compare that level of concentration to the average of the top 10 DMAs, and the average concentration of all traditional media markets in the nation. -

The Growth of Sinclair's Conservative Media Empire – the New Yorker

1/15/2019 The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire | The New Yorker Annals of Media October 22, 2018 Issue The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire The company has achieved formidable reach by focussing on small markets where its TV stations can have a big inuence. By Sheelah Kolhatkar Sinclair has largely evaded the kind of public scrutiny given to its more famous competitor, Fox News. Illustration by Paul Sahre; photograph from Blend Images / ColorBlind Images / Getty https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/22/the-growth-of-sinclairs-conservative-media-empire 1/19 1/15/2019 The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire | The New Yorker 0:00 / 45:27 Audio: Listen to this article. To hear more, download the Audm iPhone app. auren Hills knew that she wanted to be a news broadcaster in the fourth grade, when a veteran television anchor L came to speak at her school’s career day. “Any broadcast journalist will tell you something very similar,” Hills said recently, when I met her. “For a majority of us, we knew at a very young age.” She became a sports editor at her high-school newspaper, in Wellington, Florida, near Palm Beach, and then attended the journalism program at the University of Florida, in Gainesville. Before graduation, she began sending résumé tapes to dozens of TV stations in small markets, hoping for an offer. Hills showed me the list she had used in her search. Written in pen in the margin was a note to herself: “You can do it!!!!” Hills was hired as a general-assignment reporter at a channel in West Virginia, in 2005, and began covering what she called “typical small-market news”—city-council meetings and local football games.