Smithsonian Magazine: from the Editor If You Are Still Having Problems Viewing This Message, Please Click Here for Additional Help

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria: the Irg L Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R

Volume 18 Article 7 May 2019 Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R. Richwine Gettysburg College Class of 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Richwine, Lindsay R. (2019) "Victoria: The irlG Who Would Become Queen," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 18 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Abstract This research reviews the early life of Queen Victoria and through analysis of her sequestered childhood and lack of parental figures explains her reliance later in life on mentors and advisors. Additionally, the research reviews previous biographical portrayals of the Queen and refutes the claim that she was merely a receptacle for the ideas of the men around her while still acknowledging and explaining her dependence on these advisors. Keywords Queen Victoria, England, British History, Monarchy, Early Life, Women's History This article is available in The Gettysburg Historical Journal: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 Victoria: The Girl Who Would Become Queen By Lindsay Richwine “I am very young and perhaps in many, though not in all things, inexperienced, but I am sure that very few have more real good-will and more real desire to do what is fit and right than I have.”1 –Queen Victoria, 1837 Queen Victoria was arguably the most influential person of the 19th century. -

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in the Young Victoria (2009)

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in The Young Victoria (2009) Julia Kinzler (Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) Abstract This article explores the ambivalent re-imagination of Queen Victoria in Jean-Marc Vallée’s The Young Victoria (2009). Due to the almost obsessive current interest in Victorian sexuality and gender roles that still seem to frame contemporary debates, this article interrogates the ambiguous depiction of gender relations in this most recent portrayal of Victoria, especially as constructed through the visual imagery of actual artworks incorporated into the film. In its self-conscious (mis)representation of Victorian (royal) history, this essay argues, The Young Victoria addresses the problems and implications of discussing the film as a royal biopic within the generic conventions of heritage cinema. Keywords: biopic, film, gender, genre, iconography, neo-Victorianism, Queen Victoria, royalty, Jean-Marc Vallée. ***** In her influential monograph Victoriana, Cora Kaplan describes the huge popularity of neo-Victorian texts and the “fascination with things Victorian” as a “British postwar vogue which shows no signs of exhaustion” (Kaplan 2007: 2). Yet, from this “rich afterlife of Victorianism” cinematic representations of the eponymous monarch are strangely absent (Johnston and Waters 2008: 8). The recovery of Queen Victoria on film in John Madden’s visualisation of the delicate John-Brown-episode in the Queen’s later life in Mrs Brown (1997) coincided with the academic revival of interest in the monarch reflected by Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich in Remaking Queen Victoria (1997). Academia and the film industry brought the Queen back to “the centre of Victorian cultures around the globe”, where Homans and Munich believe “she always was” (Homans and Munich 1997: 1). -

A Study of the Floral Biology of Viciaria Amazonica (Poepp.) Sowerby (Nymphaeaceae)

A study of the Floral Biology of Viciaria amazonica (Poepp.) Sowerby (Nymphaeaceae) Ghillean T. Prance (1) Jorge R. Arias (2) Abstract Victoria and the beetles which visit the flowers in large numbers, and to collect data A field study of the floral biology of Victoria on V. amazonica to compare with the data of amazonica (Poepp.) Sowerby (Nymphaeaceae) was Valia & Girino (1972) on V. cruziana. made for comparison with the many studies made in cultivated plants, of Victoria in the past. In thE: study areas in the vicinity of Manaus, four species HISTORY OF WORK ON THE FLORAL of Dynastid beetles were found in flowers of V. BIOLOGY OF VICTORIA. amazonica, three of the genus Cyclocephala and one o! Ligyrus . The commonest species of beetle The nomenclatura( and taxonomic history proved to be a new species of Cyclocephala and was found in over 90 percent of the flowers studied. of the genus has already been summarized in The flowers of V. amazonica attract beetles by Prance (1974). where it has been shown that their odour and their white colour on the first the correct name for the Amazonian species day that they open. The beetles are trapped in the of Victoria is V. amazonica, and not the more flower for twenty-four hours and feed on the starchy carpellary appendages. Observations were frequently used name, V. regia. The taxonomic made of flower temperature, which is elevated up history is not treated further here. to 11 aC above ambient temperature, when the flower Victoria amazonica has been a subject of emits the odour to attract the beetles. -

Victoria, Koningin

Victoria, koningin Julia Baird ictoria Vkoningin Een intieme biografie van de vrouw die een wereldrijk regeerde Nieuw Amsterdam Vertaling Chiel van Soelen en Pieter van der Veen Oorspronkelijke titel Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire. Penguin Random House LLC, New York © 2016 Julia Baird Kaarten en stamboom © 2016 David Lindroth, Inc. © 2017 Nederlandse vertaling: Chiel van Soelen en Pieter van der Veen/ Nieuw Amsterdam Voor de herkomst van het beeldmateriaal, zie de illustratieverantwoording vanaf blz. 753 Alle rechten voorbehouden Tekstredactie Marianne Tieleman Register Ansfried Scheifes Omslagontwerp Bureau Beck Omslagbeeld: Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Victoria (1842, detail)/Bridgeman Images. Auteursportret Alex Ellinghausen nur 681 isbn 978 90 468 2179 4 www.nieuwamsterdam.nl Voor Poppy en Sam, mijn betoverende kinderen [Koningin Victoria] behoorde tot geen enkele denkbare categorie van vorsten of vrouwen, zij vertoonde geen gelijkenis met een aristocratische Engelse dame, niet met een rijke Engelse middenklassevrouw, noch met een typische prinses van een Duits hof (...). Ze regeerde langer dan de andere drie koninginnen samen. Tijdens haar leven kon ze nooit worden verward met iemand anders, en dat zal ook in de geschiedenis zo zijn. Uit- drukkingen als ‘mensen zoals koningin Victoria’ of ‘dat soort vrouw’ konden voor haar niet worden gebruikt (...). Meer dan zestig jaar lang was ze gewoon ‘de konin- gin’, zonder voor- of achtervoegsel.1 Arthur PONSONBY We kijken allemaal of we al tekenen van -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860- 1901 Charles Vincent Reed, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Richard Price Department of History ABSTRACT: The dissertation explores the development of global identities in the nineteenth-century British Empire through one particular device of colonial rule – the royal tour. Colonial officials and administrators sought to encourage loyalty and obedience on part of Queen Victoria’s subjects around the world through imperial spectacle and personal interaction with the queen’s children and grandchildren. The royal tour, I argue, created cultural spaces that both settlers of European descent and colonial people of color used to claim the rights and responsibilities of imperial citizenship. The dissertation, then, examines how the royal tours were imagined and used by different historical actors in Britain, southern Africa, New Zealand, and South Asia. My work builds on a growing historical literature about “imperial networks” and the cultures of empire. In particular, it aims to understand the British world as a complex field of cultural encounters, exchanges, and borrowings rather than a collection of unitary paths between Great Britain and its colonies. ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860-1901 by Charles Vincent Reed Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard Price, Chair Professor Paul Landau Professor Dane Kennedy Professor Julie Greene Professor Ralph Bauer © Copyright by Charles Vincent Reed 2010 DEDICATION To Jude ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is both a profoundly collective project and an intensely individual one. -

JEWELS of the EDWARDIANS by Elise B

JEWELS OF THE EDWARDIANS By Elise B. Misiorowski and Nancy K. Hays Although the reign of King Edward VII of ver the last decade, interest in antique and period jew- Great Britain was relatively short (1902- elry has grown dramatically. Not only have auction 1910), the age that bears his name produced 0 houses seen a tremendous surge in both volume of goods distinctive jewelry and ushered in several sold and prices paid, but antique dealers and jewelry retail- new designs and manufacturing techniques. ers alikereportthat sales inthis area of the industry are During this period, women from the upper- excellent and should continue to be strong (Harlaess et al., most echelons of society wore a profusion of 1992). As a result, it has become even more important for extravagant jewelry as a way of demon- strating their wealth and rank. The almost- jewelers and independent appraisers to understand-and exclusive use of platinum, the greater use of know how to differentiate between-the many styles of pearls, and the sleady supply of South period jewelry on the market. African diamonds created a combination Although a number of excellent books have been writ- that will forever characterize Edwardian ten recently on various aspects of period jewelry, there are jewels. The Edwardian age, truly the last so many that the search for information is daunting. The era of the ruling classes, ended dramatically purpose of this article is to provide an overview of one type with the onset of World War I. of period jewelry, that of the Edwardian era, an age of pros- perity for the power elite at the turn of the 19th century. -

Victoria & Abdul

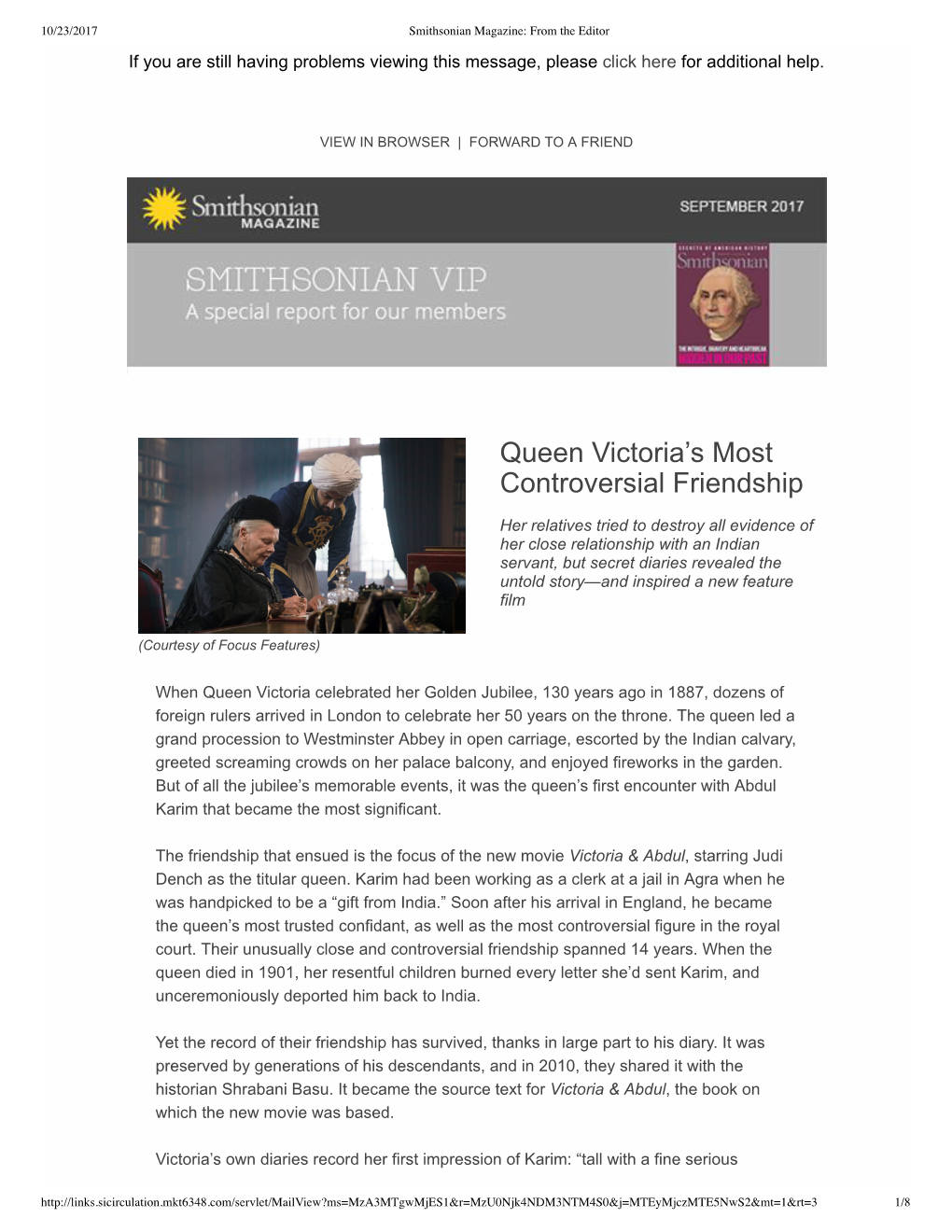

Victoria & Abdul For those Anglophiles who want another immersion in the warm, luxurious stew of the British monarchy, look no further for your latest fix than “Victoria and Abdul,” an engaging if utterly predictable dip into late Victorianism by a whole passel of old British pros, plus an attractive newcomer. All you need to know is that Dame Judi Dench rules this film as Queen Victoria, way late in her reign, alienated from her son (the future Edward VII), sour as vinegar from her unending rule, and looking for some—any—breath of the novel and the fresh. As she herself admits when challenged in the film: ”I am cantankerous, greedy, fat; I am perhaps, disagreeably, attached to power.” Her relief comes in the form of one Abdul Karim, a young, literate Indian Muslim (Ali Fazal) who is selected to come to London from Agra in 1887 to deliver a special commemorative coin to Her Majesty on the occasion of her Golden Jubilee. Abdul is supposed to be invisible to the Queen, but instead he catches her eye, then her mood, and finally, her spirit to the point where he becomes her teacher, or “munshi,” in all things Muslim and Indian as well as serving as her clerk. Theirs is a relationship which appalls her family—including the Prince of Wales (a bombastic Eddie Izzard)— and the court—especially in the person of Sir Henry Ponsonby (the uptight Tim Pigott- Smith) but which lasted until the Queen’s death in 1901. Sound familiar? Of course, we are in the same realm as the earlier “Mrs. -

FACT SHEET Frogmore House Frogmore House

FACT SHEET Frogmore House Frogmore House is a private, unoccupied residence set in the grounds of the Home Park of Windsor Castle. It is frequently used by the royal family for entertaining. It was recently used as the reception venue for the wedding of The Queen’s eldest grandson, Peter Phillips, to Autumn Kelly, in May 2008. How history shaped Frogmore The estate in which Frogmore House now lies first came into royal ownership in the 16th century. The original Frogmore House was built between 1680 and 1684 for tenants Anne Aldworth and her husband Thomas May, almost certainly to the designs of his uncle, Hugh May who was Charles II’s architect at Windsor. From 1709 to 1738 Frogmore House was leased by the Duke of NorthumberlandNorthumberland, son of Charles II by the Duchess of Cleveland. The House then had a succession of occupants, including Edward Walpole, second son of the Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole. In 1792 George III (r. 1760-1820) bought Frogmore House for his wife Queen CharlotteCharlotte, who used it for herself and her unmarried daughters as a country retreat. Although the house had been continuously occupied and was generally in good condition, a number of alterations were required to make it fit for the use of the royal family, and architect James Wyatt was appointed to the task. By May 1795, Wyatt had extended the second floor and added single- storey pavilions to the north and south of the garden front, linked by an open colonnade and in 1804 he enlarged the wings by adding a tall bow room and a low room beyond, to make a dining room and library at the south end and matching rooms at the north. -

Osborne Teachers' Resource Pack (KS2-KS3)

KS2–KS3 TEACHERS’ RESOURCE PACK Osborne This resource pack will help teachers plan a visit to Osborne, which offers unrivalled insight into the private lives of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and the empire over which they ruled. Use this pack in the classroom to help students get the most out of their learning about Osborne. INCLUDED • Historical Information • Glossary • Sources • Site Plan Get in touch with our Education Booking Team 0370 333 0606 [email protected] https://bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Don’t forget to download our Hazard Information Sheets and Discovery Visit Risk Assessments to help with planning: • The Adventures of a Victorian Explorer (KS2) • Waiting on Hand and Foot (KS2) • Story Mat (KS1) Share your visit with us on Twitter @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published January 2018 HISTORICAL INFORMATION DISCOVER THE STORY OF Below is a short history of Osborne. Use this OSBORNE information to learn how the site has changed over time. You will find definitions of the key words in the Glossary. AN EXCELLENT HOME In October 1843, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were looking for a new country home for their ever-growing family. The royal couple visited the Osborne estate in 1844 and Victoria was delighted with how private it was: ‘…we can walk anywhere without being mobbed or followed.’ Best of all, it had Osborne House was built of brick its own beach where they could come and with a smooth cement layer on top to make the house look as if go by boat without being seen. -

Mrs Brown by Jeremy Brock Ext. the Grounds Of

MRS BROWN BY JEREMY BROCK EXT. THE GROUNDS OF WINDSOR CASTLE, FOREST - NIGHT Begin on black. The sound of rain driving into trees. Something wipes frame and we are suddenly hurtling through a forest on the shoulders of a wild-eyed, kilted JOHN BROWN. Drenched hair streaming, head swivelling left and right, as he searches the lightening-dark. A crack to his left. He spins round, raises his pistol, smacks past saplings and plunges on. EXT. THE GROUNDS OF WINDSOR CASTLE, FOREST - NIGHT Close-up on BROWN as he bangs against a tree and heaves for air. A face in its fifties, mad-fierce eyes, handsome, bruised lips, liverish. He goes on searching the dark. Stops. Listens through the rain. A beat. Thinking he hears a faint thump in the distance, he swings round and races on. EXT. THE GROUNDS OF WINDSOR CASTLE, FOREST - NIGHT BROWN tears through the trees, pistol raised at full arm's length, breath coming harder and harder. But even now there's a ghost grace, a born hunter's grace. He leaps fallen branches, swerves through turns in the path, eyes forward, never stumbling once. EXT. THE GROUNDS OF WINDSOR CASTLE, FOREST - NIGHT BROWN bursts into a clearing, breaks to the centre and stops. With his pistol raised, he turns one full slow circle. His eyes take in every swerve and kick of the wildly swaying trees. There's a crack and a branch snaps behind him. He spins round, bellows deep from his heart: BROWN God save the Queen!! And fires. Nothing happens. The trees go on swaying, the storm goes on screaming and BROWN just stands there, staring into empty space. -

Programme East Cowes 2019

PROGRAMME EAST COWES 2019 24 -27 MAY May - 4th to 2nd June Open every Thursday to Sunday 11am to 4pm BEYOND THE RED ROPE - A Contemporary Art Installation @ Space5. This is a selection of works first exhibited at Osborne House in 2015. From May 24th - 10.00 TO 5.00 OSBORNE HOUSE BIRTHDAY TRAIL – The trail is contained within the house and exhibits the gifts exchanged between Victoria and Albert. May - 24th - 4.30 OPENING OF THE QUEEN VICTORIA TRAIL - The Mayors of Coburg & East Cowes and Her Excellency, The Indian High Commissioner will open the trail in the entrance grounds of Osborne House. This is followed by the first Guided Tour of the trail. 4.45 Laying of flowers at the Abdul Karim Stone, near the Gate House of Osborne House, by his descendants. 6.30 CIVIC RECEPTION and opening of the Victorian Grand Exhibition (By Invitation) May - 25th- 9.30 GRAND EXIBITION - The Queen Victoria Lifeboat on display outside the Town Hall. 10.00 – 3.00 VICTORIAN DAY - Kings Square, Music and Children’s Swing Boats, Best Dressed Victorian, Morris dancers in the square and around the Umbrella Tree. 10.00 CHURCHES TOGETHER - The Romanov Monument, Jubilee Recreation Ground, York Ave. Blessing of V&A Memorial Bench. 7.30 TOWN SHOW - Victorian Time Machine at the Town Hall. Tickets £5 at the door. May - 26th - 9.30 – 5.00 GRAND EXHIBITION – East Cowes Town Hall 10.00 RNLI INSHORE CENTRE OPEN DAY - Opposite the East Cowes Marina. Tours of the lifeboat Manu- facture Centre, Music and RNLI display. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

Teresa Sorolla-Romero La reina del (melo)drama. La representación cinematográfica de Victoria del Reino Unido 105 La reina del (melo)drama. La representación cinematográfica de Victoria del Reino Unido The (Melo)Drama Queen. Filmic Representations of Queen Victoria Teresa Sorolla-Romero Universitat Jaume I Recibido: 20/04/2019 Evaluado: 05/06/2019 Aprobado: 05/06/2019 Resumen: En este texto nos proponemos destacar los aspectos más signi- ficativos de las estrategias de representación –estéticas y narrativas– que entretejen los discursos de los filmes dedicados a Victoria del Reino Unido durante las dos primeras décadas del siglo xxi: The Young Victoria (Jean- Marc Valleé, 2009), Mrs. Brown (John Madden, 1997) y Victoria & Abdul (Stephen Frears, 2017) identificando qué elecciones biográficas son desta- can en ellas –qué aspectos se enfatizan, omiten o inventan– con el fin de comprender los mecanismos de articulac ión de las diferentes imágenes fílmicas de la monarca británica y emperatriz de la India. Palabras clave: Victoria del Reino Unido; monarquía británica; drama de época; biopic. Abstract: In this article we intend to focus on the most significant as- pects of the aesthetic and narrative strategies which interwave the filmic discourses devoted to Victoria of the United Kingdom along the first two decades of the 21st century: The Young Victoria (Jean-Marc Valleé, 2009), Mrs. Brown (John Madden, 1997) and Victoria & Abdul (Stephen ISSN: 1888-9867 | e-ISSN 2340-499X | http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Potestas.2019.14.5 106 POTESTAS, No 14, junio 2019 | pp. 105-141 Frears, 2017). Our aim is to identify which biographical choices are em- phasized –that is, which facets are highlighted, omitted or invented– in order to understand which mechanisms articula te several filmic images of the British monarch and Empress of the India.