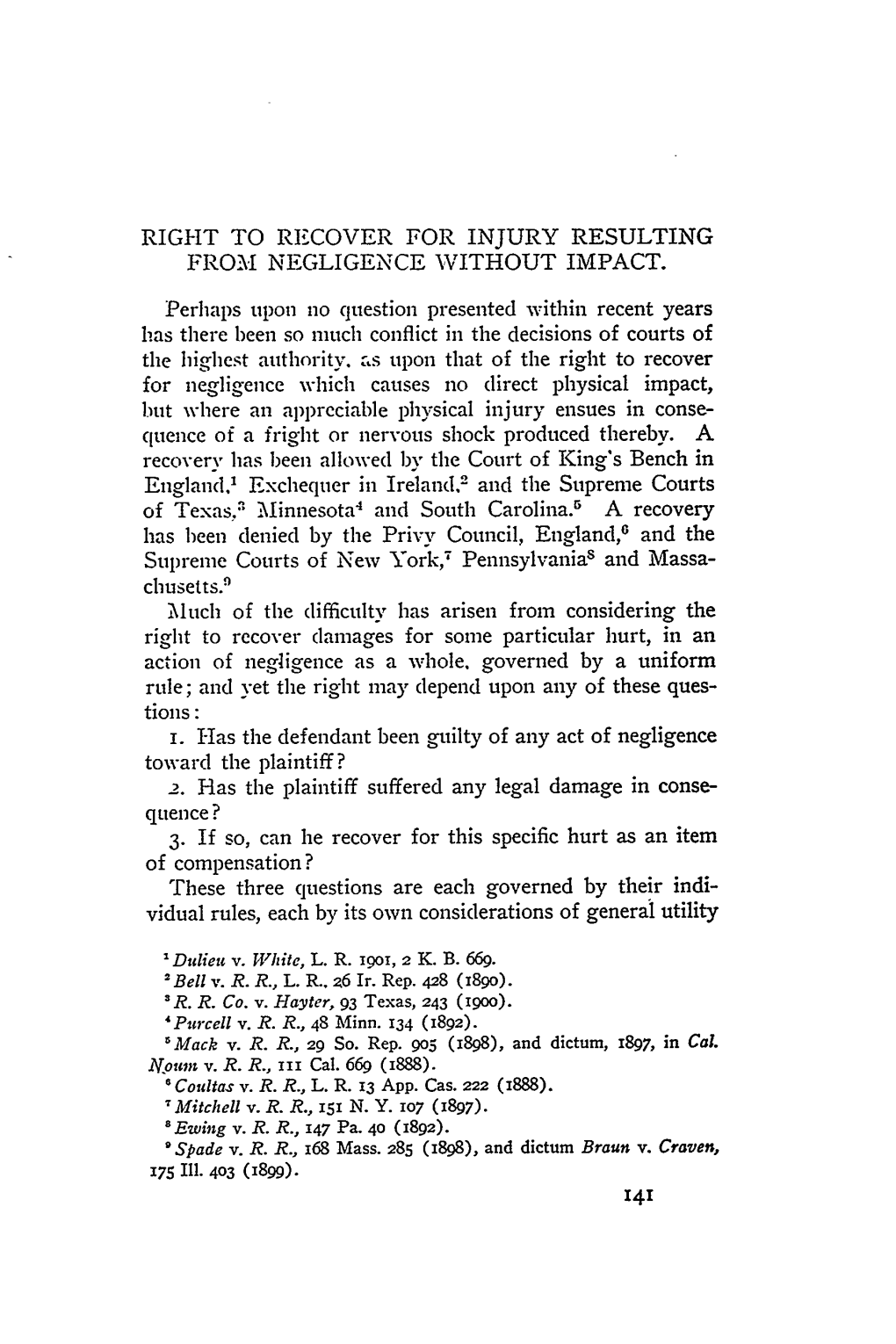

Right to Recover for Injury Resulting from Negligence Without Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotion, Seduction and Intimacy: Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R

Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/2619/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. (2010). Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour. Silent Revolution Series . Seattle, Libertary Editions. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Silent Revolution Series Emotion Seduction & Intimacy Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour Third Edition © Dr Rory Ridley-Duff, 2010 Edited by Dr Poonam Thapa Libertary Editions Seattle © Dr Rory Ridley‐Duff, 2010 Rory Ridley‐Duff has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial‐No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. -

Agreement and Release of All Claims

SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT AND RELEASE OF ALL CLAIMS This Settlement Agreement and Release of All Claims (“Agreement”) is made and entered into by and between ANDRES ALEXANDER CACEDA-MANTILLA and CITY OF PALMER, ALASKA (hereinafter collectively referred to as “the Parties”). “Claimant” shall collectively mean Andres Alexander Caceda-Mantilla and his respective heirs, executors, administrators, successors, trustees, and assigns. “Released Party” shall collectively mean City of Palmer, Alaska, and its respective, employees, assigns, heirs, agents, attorneys, adjusters, insurers, and re-insurers. I. Recitals A. The purpose this Agreement is to facilitate the settlement, dismissal with prejudice, and release of any and all claims which were asserted, or which could have been asserted, with respect to the facts giving rise to Andres Alexander Caceda-Mantilla v. City of Palmer, Alaska, Kristi Muilenburg, Jamie Hammons, Daniel Potter, and Hilary Schwaderer, Case No. 3PA-18-01410 CI, a lawsuit now pending in the Superior Court for the State of Alaska at Palmer (“the Lawsuit”). B. The City of Palmer denies all the allegations of the Lawsuit and specifically denies that it has any liability based on the allegations set forth in the Lawsuit. C. The City of Palmer regrets any inconvenience, embarrassment, or personal hardship the incident may have caused Mr. Caceda-Mantilla. D. The Parties desire to enter into this Agreement to provide, among other things, for consideration in full settlement and discharge of all claims and actions of {00821062} SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT AND RELEASE OF ALL CLAIMS Andres Alexander Caceda-Mantilla v. City of Palmer, Alaska, et al., Case No. 3PA-18-01410 Civil Page 1 of 9 Claimant for damages that allegedly arose out of, or due to, the facts and circumstances giving rise to the Lawsuit, on the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement. -

The Hand Formula in the Draft "Restatement (Third) of Torts": Encompassing Fairness As Well As Efficiencyalues V

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 54 Issue 3 Issue 3 - Symposium: The John W. Wade Conference on the Third Restatement of Article 10 Torts 4-2001 The Hand Formula in the Draft "Restatement (Third) of Torts": Encompassing Fairness as Well as Efficiencyalues V Kenneth W. Simons Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth W. Simons, The Hand Formula in the Draft "Restatement (Third) of Torts": Encompassing Fairness as Well as Efficiencyalues, V 54 Vanderbilt Law Review 901 (2001) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol54/iss3/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hand Formula in the Draft Restatement (Third) of Torts: Encompassing Fairness as Well as Efficiency Values Kenneth W. Simons* I. THE DRAFT RESTATEMENTS DEFINITION OF NEGLI- GENCE ............................................................................... 902 II NEGLIGENCE AND FAULT ................................................... 905 III. THE DRAFT's NEGLIGENCE CRITERION AND ECONOMIC EFFICIENCY ..................................................... 906 A. DistinguishingTradeoffs from Economic Efficiency ................................................................ 908 B. DistinguishingEx Ante Balancingfrom Consequentialism.................................................. -

The Seduction of Innocence: the Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 95 Article 7 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2005 The educS tion of Innocence: The Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy Carol S. Steiker Jordan M. Steiker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Carol S. Steiker, Jordan M. Steiker, The eS duction of Innocence: The ttrA action and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy, 95 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 587 (2004-2005) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-41 69/05/9502-0587 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 95, No. 2 Copyright 0 2005 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in US.A. THE SEDUCTION OF INNOCENCE: THE ATTRACTION AND LIMITATIONS OF THE FOCUS ON INNOCENCE IN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LAW AND ADVOCACY CAROL S. STEIKER"& JORDAN M. STEIKER** INTRODUCTION Over the past five years we have seen an unprecedented swell of debate at all levels of public life regarding the American death penalty. Much of the debate centers on the crisis of confidence engendered by the high-profile release of a significant number of wrongly convicted inmates from the nation's death rows. Advocates for reform or abolition of capital punishment have seized upon this issue to promote various public policy initiatives to address the crisis, including proposals for more complete DNA collection and testing, procedural reforms in capital cases, substantive limits on the use of capital punishment, suspension of executions, and outright abolition. -

The Great Spill in the Gulf . . . and a Sea of Pure Economic Loss: Reflections on the Boundaries of Civil Liability

The Great Spill in the Gulf . and a Sea of Pure Economic Loss: Reflections on the Boundaries of Civil Liability Vernon Valentine Palmer1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Event and Aftermath What has been called the greatest oil spill in history, and certainly the largest in United States history, began with an explosion on April 20, 2010, some 41 miles off the Louisiana coast. The accident occurred during the drilling of an exploratory well by the Deepwater Horizon, a mobile offshore drilling unit (MODU) under lease to BP (formerly British Petroleum) and owned by Transocean.2 The well-head blowout resulted in 11 dead, 17 injured, and oil spewing from the seabed 5,000 ft. below at an estimated rate of 25,000-30,000 barrels per day.3 The Deepwater Horizon is technically described as “a massive floating, dynamically positioned drilling rig” capable of operating in waters 8,000 ft. deep.4 In maritime law, such a rig qualifies as a vessel; yet, as a MODU, the rig also qualifies as an offshore facility that may attract higher liability limits under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA).5 Under these provisions the double designation as vessel and/or MODU 1. Thomas Pickles Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Eason Weinmann Center for Comparative Law, Tulane University. This paper was presented in October 2010 in Hong Kong at a conference convened under the auspices of the Centre for Chinese and Comparative Law of the City University of Hong Kong. The conference theme was “Towards a Chinese Civil Code: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.” The conference papers will be published in a forthcoming volume edited by Professors Chen Lei and Remco van Rhee. -

GUZMAN Delivered the Opinion of the Court

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS 444444444444 NO. 14-0067 444444444444 MIRTA ZORRILLA, PETITIONER, v. AYPCO CONSTRUCTION II, LLC AND JOSE LUIS MUNOZ, RESPONDENTS 4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 ON PETITION FOR REVIEW FROM THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRTEENTH DISTRICT OF TEXAS 4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 Argued March 26, 2015 JUSTICE GUZMAN delivered the opinion of the Court. In this residential construction dispute, the paramount issue on appeal is whether the statutory cap on exemplary damages is waived if not pleaded as an affirmative defense or avoidance. See TEX. R. CIV. P. 94 (requiring pleading and proof of affirmative defenses and avoidances); see also TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 41.008(b) (limiting exemplary damages to the greater of $200,000 or two times economic damages plus noneconomic damages not exceeding $750,000). Our courts of appeals are split on the issue, and in this case, the lower court affirmed an exemplary damages award in excess of the statutory cap because the petitioner did not assert the cap until her motion for new trial. 421 S.W.3d 54, 68-69 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi 2013). We hold the exemplary damages cap is not a “matter constituting an avoidance or affirmative defense” and need not be affirmatively pleaded because it applies automatically when invoked and does not require proof of additional facts. See TEX. R. CIV. P. 94. Here, the petitioner did not plead the statutory cap but she timely asserted the cap in her motion for new trial. We therefore reverse the court of appeals’ judgment in part and render judgment capping exemplary damages at $200,000. -

TORTS I PROFESSOR DEWOLF Summer 1994 July 8, 1994 MID-TERM SAMPLE ANSWER

TORTS I PROFESSOR DEWOLF Summer 1994 July 8, 1994 MID-TERM SAMPLE ANSWER QUESTION 1 I would consider claims against Larry Lacopo ("LL") and the Azure Shores Country Club. To establish liability, it would need to be proven that one of the parties breached a duty to Jason, either by being negligent or engaging in an activity for which strict liability is imposed, and that such a breach of duty was a proximate cause of injuries to him. Lacopo's Potential Liability We would argue that LL was negligent in striking the ball so hard without shouting "Fore!" To establish negligence, we would have to persuade the jury that a reasonably prudent person in the same or similar circumstances would have behaved differently. Perhaps reasonable golfers are aware of the need to avoid shots like the one that LL made; on the other hand, perhaps LL could convince the jury that he reasonably believed that the golf course had been designed so that shots would not pose a danger to anyone else. If the jury found LL negligent in hitting the ball so hard without having the skill to control it, then it would be easy to establish proximate cause. On the other hand, if the jury found that he should have shouted "Fore!" then it would still need to be shown that that failure was a proximate cause of injury. A jury would have to find that, more probably than not, the injury would not have occurred but for LL's negligence. Perhaps Jason or his grandfather would testify that, had someone shouted "Fore!" they would have at least kept an eye out for stray balls. -

Claims of Wrongful Life and Wrongful Birth - NY by Victoria Belniak

October 2006 Health Care Law Claims of wrongful life and wrongful birth - NY By Victoria Belniak Background The New York courts have long struggled with determining what injuries are properly compensable when a child is born impaired, and the parents are able to establish that a health care provider was negligent in failing to detect the impairment prenatally or to advise the parents of the likelihood of the impairment. Typically, in such cases, parents will argue that had they been advised of the impairment before the child was born, they would have chosen to terminate the pregnancy. In wrestling with the thorny damages issues presented by such cases, the New York courts have made a distinction between damages stemming from “wrongful life” and those stemming from “wrongful birth.” Issues What is the difference between a claim for wrongful life and one for wrongful birth, and can recovery be had under such theories? Comments Wrongful life claims are typically initiated on behalf of an impaired infant, seeking to recover damages for the very fact that he or she was born at all. The New York courts have rejected such claims, signaling an unwillingness to hold that life, even if marred by disability or disease, is a compensable injury. In Alquijay v. St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, 63 N.Y.2d 978, 473 N.E.2d 244 (1984), a mother claimed that had she known that her baby would be born with Down’s syndrome, she would have terminated the pregnancy. The Court of Appeals held that there is no cause of action for wrongful life, and life, even when the baby is born in an impaired state, does not constitute an injury. -

Yale Law Journal

YALE LAW JOURNAL SUISCRIPTIOH PRICE, $2.65 A YEAR. SINGLE COPIES, 35 CENTS. EDITORIAL BOARD. JOHN F. BAKER, Chairman. FRANx KENNA, Graduate, FLAVEL ROBERTSON, Business Manager. Secretary. JOSEP1H A. ALLARD, JR., JAMES A. STEVENSON, JR. HENRY C. CLARK, BUCKINGHAM P. MERRIMAN, ALEXANDER W. CREEDON, C. FLOYDE GRIDER, CLEAVELAND J. RICE, THOMAS C. FLOOD, LEONARD 0. RYAN, IRVING M. ENGEL, Published monthl from November to June, by students of the Yale Law School. P . Address, Box 893, Yale Station, New Haven, Conn. If a subscriber wishes his copy of the JOURNAL discontinued at the expiration of his subscription, notice to that effect should be sent; otherwise, it is assumed that a continuation of the subscription is desired. LIABILITY OF A CHARITABLE INSTITUTION FOR THE NEGLIGENCE OF ITS SERVANTS. The rules in regard to liability for negligence are pretty firmly established and, in the main, with but little diversity between the several states. Especially well established is the rule of respond- eat superior,which requires the master to stand responsible for all damage resulting from the negligence of his servant, while acting in his capacity as such. There is, however, one notable exception to the settled applicability of this rule, namely, the responsibility of a charitable corporation for the negligence of its servants. Here there are various elements which have given rise to much discussion and make the question of the application of the rule an interesting one. The latest case dealing with this question is Taylor v. Protestant Hospital Association, 96 N. E. (Ohio), 1O89. The facts were that the defendant association received a woman at its hospital as a pay patient and agreed, for a valuable consideration, to fur- nish her with board, lodging, nursing, etc., and assist in and about an operation to be performed on her by a certain named surgeon. -

The Metropolitan Corporate Counsel: Are Punitive Damages Available

CorporateThe Metropolitan Counsel® www.metrocorpcounsel.com Volume 13, No. 3 © 2005 The Metropolitan Corporate Counsel, Inc. March 2005 Are Punitive Damages Available Under The Copyright Act? Marc J. Rachman Sara L. Edelman and David Greenberg DAVIS & GILBERT LLP Given the Copyright Act’s1 express enu- meration of available remedies under the Act and its silence with respect to punitive damages, one would think that a copyright owner is barred from seeking punitive damages when bringing a claim for copy- Marc J. Rachman Sara L. Edelman David Greenberg right infringement. Several recent deci- sions in the Southern District of New York, profits of the infringer... or ... statutory statutory damages amount. however, have allowed punitive damages damages....” 2 A copyright owner may elect The Second Circuit United States Court claims to proceed. This article will discuss to recover statutory damages at any time of Appeals long ago stated explicitly that the traditional view that punitive damages prior to final judgment; such damages can “[p]unitive damages are not available in are not available under the Copyright Act, range anywhere from as little as $200 for statutory copyright actions.” 6 That court and will explore recent decisions indicating innocent infringements to $150,000 for recently explained that “[t]he purpose of that such damages might be recoverable willful infringements.3 Notably, Congress punitive damages – to punish and prevent under certain circumstances. This article made no provision in the Act for awards of malicious conduct – is generally achieved will then discuss the implications for both punitive damages. “The language is clear, under the Copyright Act through the provi- plaintiffs and defendants, and will finally unambiguous, and exclusive: these are the sions of 17 U.S.C. -

Told Nervous Shock

TOLD NERVOUS SHOCK : HAS THE PENDULUM SWUNG IN FAVOUR OF RECOVERY BY TELEVISION VIEWERS ? RAMANAN RAJENDRAN * [‘Nervous shock’ was recognised as a recoverable form of injury in the early 1900s. Only recently however this form of injury has received extended coverage in the High Court of Australia and the legislature. Unfortunately, there are few clear guidelines, especially from the High Court judgments. This article discusses the implication of the recent decisions of Tame and Annetts and Gifford , as well as the history of ‘nervous shock’ and statutory developments. It seeks to clarify the ap- proach of the High Court and the legislature in the area of nervous shock, espe- cially as it relates to recovery for ‘nervous shock’ by viewers of distressing events on television. ] I INTRODUCTION In a litigious society, it is all too easy to regard as frivolous claims for psychiatric illness, especially when there is no accompanying physical injury. After all, it is generally invisible to the untrained eye and seeing is believing. Psychiatric injury (often referred to as ‘nervous shock’) is neither trivial nor frivolous and is now generally recognised by both the legal and medical professions as worthy of recov- ery. As Gummow and Kirby JJ noted in Tame and New South Wales and Annetts v 732 DEAKIN LAW REVIEW VOLUME 9 NO 2 Australian Stations Pty Ltd,1 there have been advances in the capacity of medicine to objectively distinguish the genuine from the spurious. This topic is set to receive attention by the NSW Supreme Court, in Klein v New South Wales ,2 following Master Harrison’s decision not to rule in favour of an application by the Defendant to strike out the Plaintiffs’ Statement of Claim. -

Alienation of Affection Suits in Connecticut a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2006-2020, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2020 Edition Alienation of Affection Suits in Connecticut A Guide to Resources in the Law Library This guide is no longer being updated on a regular basis. But we make it available for the historical significance in the development of the law. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Spousal Alienation of Affection ............................................................ 4 Table 1: Spousal Alienation of Affections in Other States ....................................... 8 Table 2: Brown v. Strum ................................................................................... 9 Section 2: Criminal Conversation ..................................................................... 11 Table 3: Criminal Conversation in Other States .................................................. 14 Section 3: Alienation of Affection of Parent or Child ............................................ 15 Table 4: Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ............................................ 18 Table 5: Campos v. Coleman ........................................................................... 20 Prepared by Connecticut Judicial Branch, Superior Court Operations, Judge Support Services, Law Library Services Unit [email protected] Alienation-1 These guides are provided with the understanding that they represent