Examine the Value of Place-Names As Evidence for the History, Landscape and Language(S) of Your Chosen Area

Total Page:16

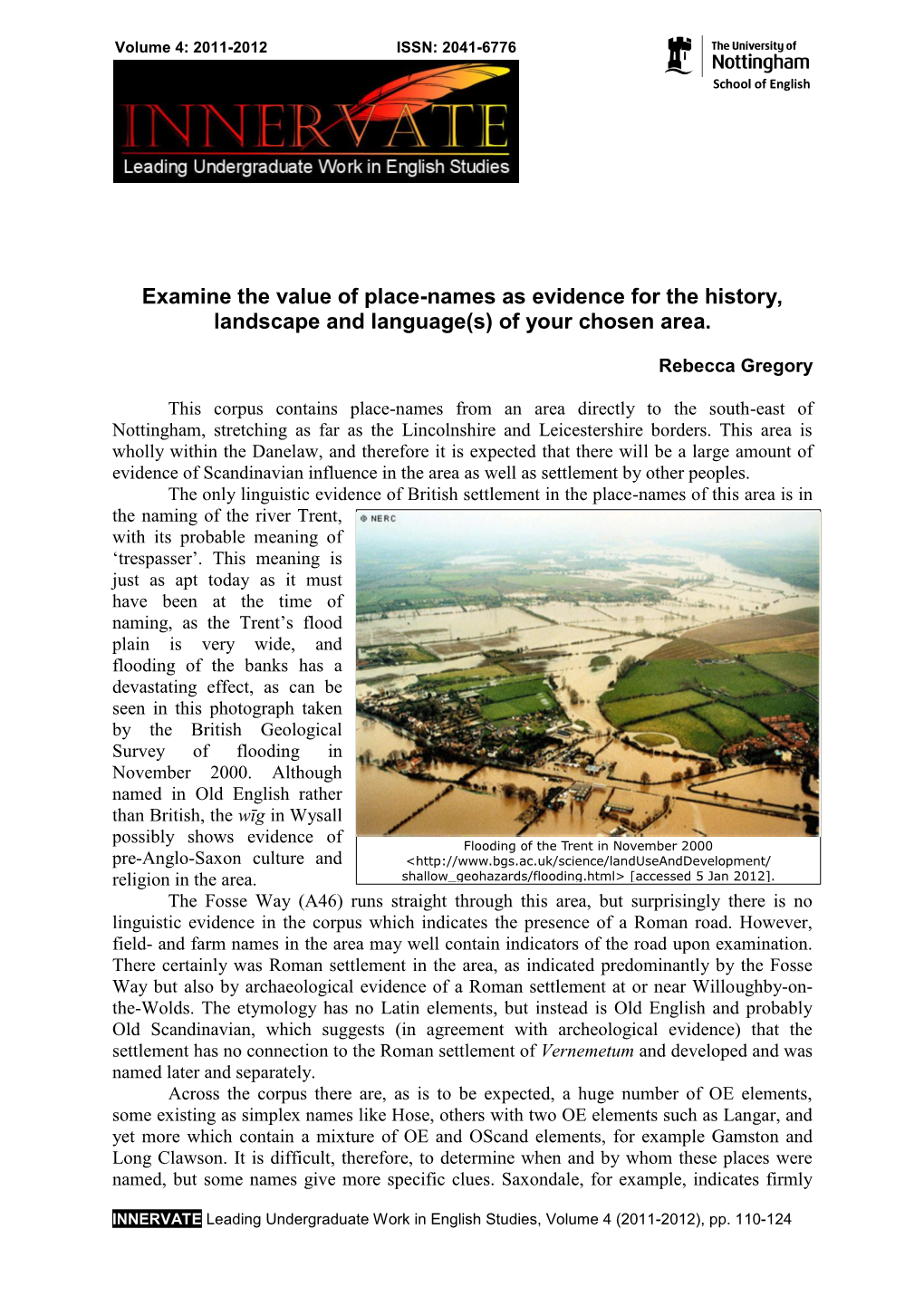

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroton Society Publications

THOROTON SOCIETY Record Series Blagg, T.M. ed., Seventeenth Century Parish Register Transcripts belonging to the peculiar of Southwell, Thoroton Society Record Series, 1 (1903) Leadam, I.S. ed., The Domesday of Inclosures for Nottinghamshire. From the Returns to the Inclosure Commissioners of 1517, in the Public Record Office, Thoroton Society Record Series, 2 (1904) Phillimore, W.P.W. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. I: Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485 to 1546, Thoroton Society Record Series, 3 (1905) Standish, J. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. II: Edward I and Edward II, 1279 to 1321, Thoroton Society Record Series, 4 (1914) Tate, W.E., Parliamentary Land Enclosures in the county of Nottingham during the 18th and 19th Centuries (1743-1868), Thoroton Society Record Series, 5 (1935) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem and other Inquisitions relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. III: Edward II and Edward III, 1321 to 1350, Thoroton Society Record Series, 6 (1939) Hodgkinson, R.F.B., The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and St. Mary in the church of St. Peter, Nottingham, Thoroton Society Record Series, 7 (1939) Gray, D. ed., Newstead Priory Cartulary, 1344, and other archives, Thoroton Society Record Series, 8 (1940) Young, E.; Blagg, T.M. ed., A History of Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, Thoroton Society Record Series, 9 (1942) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Bonds and Allegations for Marriage Licenses in the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham, 1754-1770, Thoroton Society Record Series, 10 (1947) Blagg, T.M. -

The Influence of Old Norse on the English Language

Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS AND KIDS: THE INFLUENCE OF OLD NORSE ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS E KIDS: A INFLUÊNCIA DO NÓRDICO ANTIGO NA LÍNGUA INGLESA Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars1 Abstract: What have common English words such as husbands, outlaws and kids and the sentence they are weak to do with Old Norse? Yet, all these examples are from Old Norse, the Norsemen’s language. However, the Norse influence on English is underestimated as the Norsemen are viewed as barbaric, violent pirates. Also, the Norman occupation of England and the Great Vowel Shift have obscured the Old Norse influence. These topics, plus the Viking Age, the Scandinavian presence in England, as well as the Old Norse linguistic influence on English and the supposed French influence of the Norman invasion will be described. The research for this etymological article was executed through a descriptive- qualitative approach. Concluded is that the Norsemen have intensively influenced English due to their military supremacy and their abilities to adaptation. Even the French-Norman French language has left marks on English. Nowadays, English is a lingua franca, leading to borrowings from English to many languages, which is often considered as invasive. But, English itself has borrowed from other languages, maintaining its proper character. Hence, it is hoped that this article may contribute to a greater acknowledgement of the Norse influence on English and undermine the scepticism towards the English language as every language has its importance. Keywords: Old Norse Loanwords, English Language, Viking Age, Etymology. Resumo: O que têm palavras inglesas comuns como husbands, outlaws e kids e a frase they are weak a ver com os Nórdicos? Todos esses exemplos são do nórdico antigo, a língua dos escandinavos. -

The Carboniferous Bowland Shale Gas Study: Geology and Resource Estimation

THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation i © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Disclaimer This report is for information only. It does not constitute legal, technical or professional advice. The Department of Energy and Climate Change does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss or damage of any nature, however caused, which may be sustained as a result of reliance upon the information contained in this report. All material is copyright. It may be produced in whole or in part subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source, but should not be included in any commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the written permission of the Department of Energy and Climate Change. Suggested citation: Andrews, I.J. 2013. The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation. British Geological Survey for Department of Energy and Climate Change, London, UK. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to: Toni Harvey Senior Geoscientist - UK Onshore Email: [email protected] ii © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Foreword This report has been produced under contract by the British Geological Survey (BGS). It is based on a recent analysis, together with published data and interpretations. Additional information is available at the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) website. https://www.gov.uk/oil-and-gas-onshore-exploration-and-production. This includes licensing regulations, maps, monthly production figures, basic well data and where to view and purchase data. -

Village Newsletter for Hickling and Hickling Pastures

The Village Newsletter for Hickling and Hickling Pastures 5th e-issue February - March 2021 44 Hickling Local History1 Group Hickling Village Newsletter - Committee Chair; Tim McEwen - Tel. 822834 or [email protected]) Treasurer/Advertising; Andrew Terry } Tel. 822088 or Copy & Secretary; Maggy Jordan } [email protected] Copy Collection; Jane Fraser - Tel. 822845 Please get in touch with any of us if you have any comments or suggestions. We would welcome any contributions for future issues - articles, opinions, reports, recipes, poems, brain-teasers - whatever you would like to see in print! 2021 Copy Dates; April/May 15.3.21 June/July 15.5.21 The nursery is split into 3 separate rooms which enables us Copy must be received before these dates to guarantee its appearance. Pea Pod Day Nursery is a small, to promote a home from home Please note that the committee reserve the right to edit or omit any material family run 29 place day nursery experience with a very friendly, submitted. Opinions expressed in published articles remain the at Hickling Pastures, on the warm environment and in our rural responsibility of the author. Articles may be published anonymously but the A606 between Melton and setting the children have the committee does need to have details of authorship before publication. Nottingham, only a few yards opportunity to explore open fields from the A46 roundabout. and have access to a number of If you are submitting articles ready for publication - (either typed or in different animals. computer format) we would be grateful if you could send it in A5 size. -

Form 4A (Rule 6.2) Public Notice (General Form) in the Consistory Court of the Diocese of Southwell & Nottingham

Ref: 2020-049572 Church: Holme Pierrepont w Adbolton: St Edmund Diocese: Southwell & Nottingham Archdeaconry: Nottingham Form 4A (Rule 6.2) Public Notice (general form) In the Consistory Court of the Diocese of Southwell & Nottingham Church of Holme Pierrepont w Adbolton: St Edmund In the parish of Holme Pierrepont and Adbolton NOTICE IS GIVEN that we are applying to the Consistory Court of the diocese for permission to carry out the following: 1 To replace existing failing lighting system with a new scheme in the Nave 2 To replace 3 central aisle lights with 2 banks x 4 lights over both banks of pews and to install spot lights (4x north side + 4 south side) where the walls meet the roof. Both sets of lights will be separately operated 3 To replace 2 lights in the south aisle. 4 All in accordance with quotation dated 3 March 2020 from Crew Electrical, West Bridgford, Nottingham and full details of lighting from Hacel Lighting Ltd, Wallsend, Newcastle upon Tyne dated 31 January 2020 Copies of the relevant plans and documents may be examined at Please contact Brenda Stevenson on 0115 974 9700 (If changes to a church are proposed, a copy of the petition and of any designs, plans, photographs and other documents that were submitted with it must be displayed in the church or at another place where they may be conveniently inspected by the public.) Petitioners: 1. BRENDA STEVENSON, EX CHURCHWARDEN - RESIGNED 31.1.2020 DUE TO ILL HEALTH 2. IAN GODSON, LAY PCC CHAIR & TEMPORARY CHURCH WARDEN 3. Date 14/05/2020 If you wish to object to any of the works or proposals you should send a letter stating the grounds of your objection to The Diocesan Registrar at Jubilee House Westgate Southwell Nottinghamshire NG25 0JH so that your letter reaches the registrar not later than 13/06/2020. -

Leices'rershire. [KILLY's Harriman John, Market Gardener Hubbard Samuel, Royal P.H

BROVGBTON .ASTLEY. LEICEs'rERSHIRE. [KILLY'S Harriman John, market gardener Hubbard Samuel, Royal P.H. &; butcher IMartin Harriet (Mrs.), farmer Hopkins William, farmer IHunt William, farmer Tite Edmund, jobbing gardener NETHER BROUGHTON is a village and parish on of Caius College, Cambridge, and rural dean of Framland the borders of Nottinghamslure, 1~ miles north-east from third portion. A National school was built here in 1845 and Old Dalby station on the Melton and Nottingham branch of enlarged to hold 100 in 1847, by the Rev. John Noble B.A. the Midland line, 6 miles north-west from Melton Mowbray late rector, and is now used for the purposes of a Church and 121 from London by rail, in the Eastern division of the Sunday school and for parish meetings. A Wesleyan chapel county, Framland hundred, Melton Mowbray union, petty was built in 1829. Here are charities (left 1682), producing sessional division and county court district, rural deanery of about £7 yearly. There are no manorial rights. A.. Lang Framland third portion, archdeaconry of Leicester and ham esq. and Seymour Pleydell Bouverie esq. are the prin diocese of Peterborough. The church of St. Mar,V is a cipal landowners. The soIl is heavy clay; subsoil, clay. building of stone in the Gothic style of the 14th century, The chief crops are turnips, wheat, oats and barley, with a consisting of chancel, clerestoried nave of three bays, aisles lal'ge quantity of pasture. The area is 2,230 acres; rate and an embattled tower with pinnacles, containing 3 bells, able value, £4,084; in 1881 the population was 454. -

Annual Review 2016

nationalchurchestrust.org facebook.com/nationalchurchestrust @natchurchtrust flickr.com/photos/nationalchurchestrust vimeo.com/nationalchurchestrust Instagram.com/nationalchurchestrust You can support the work of the National Churches Trust by making a donation online at www.nationalchurchestrust.org/donate The National Churches Trust 7 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QB Telephone: 020 7222 0605 Web: www.nationalchurchestrust.org Email [email protected] St Catherine’s church, Temple, Cornwall For people who love church buildings Published by The National Churches Trust ©2017 Company registered in England Registration number 06265201 Annual Review Registered charity number 1119845 2016 – 2017 Printed by Gemini Print Southern Ltd Designed by GADS Limited Contents Patron Chairman’s Introduction .............................................4 Her Majesty The Queen The Year in Review ........................................................5 Vice Patron HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG GCVO ARIBA Grants Programme .................................................... 14 Presidents Bill Bryson, ExploreChurches ................................. 19 The Archbishop of Canterbury The Archbishop of York Lucy Winkett, Using our church buildings ........ 22 Vice Presidents Catherine Pepinster, Joseph Hansom – Bill Bryson OBE A Victorian great ........................................................ 24 Sarah Bracher MBE Lord Cormack FSA Dr Matthew Byrne, English Parish Churches Robin Cotton MBE Huw Edwards and Chapels ................................................................ -

Tealby, the Taifali, and the End of Roman Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire History and Archaeology Vol. 46, 2011 be observed on the Continent with Old Danish tafl, then we would expect this place-name to be morphologically similar to Danish names of same type (for example, Tavlgaarde and Tavlov), and this is even more true if the first element was in fact Old Danish tafl.4 In sum, the recorded early spellings of Tealby such as Tavelesbi and Teflesbi, with their regular medial -es-, are difficult to Tealby, the Taifali, and the end of explain as deriving either from Old English tæfl or Old Roman Lincolnshire Danish tafl, and as a result recent commentators have tended to reject such an origin for the place-name Tealby.5 Thomas Green If the place-name Tavelesbi/Teflesbi cannot be explained in the above manner, how then ought it to be accounted The origin of the Lincolnshire place-name Tealby – for? At present, the only viable etymology for the name early forms of which include Tavelesbi, Tauelesbi and appears to be that advanced by John Insley and Kenneth Teflesbi1 – is not a topic that has, thus far, excited very Cameron. They argue that the early spellings of Tealby much interest from historians of the late and post-Roman suggest that what we actually have here is an Old English periods in Britain. In some ways this is understandable, tribal or population-group name, the *Tāflas/*Tǣflas, given that the second element of Tealby is clearly Old this being the Old English form of the well-attested Danish -bȳ, ‘farm, village’, which suggests that the name Continental tribal-name Taifali. -

Approved Premises in Nottinghamshire

Appendix A List of Approved Premises in Nottinghamshire Premises name Location Beeston Fields Golf Club Wollaton Road, Beeston Bestwood Lodge Hotel Bestwood Country Park, Arnold Blackburn House, Brake Lane, Boughton, Newark Blotts Country Club Adbolton Lane, Holme Pierrepont Bramley Suite The Bramley Centre, King Street, Southwell Charnwood Hotel Sheffield Road, Blyth, Worksop Clumber Park The National Trust, Worksop Clumber Park Hotel and Spa Worksop Cockliffe Country House Burntstump Country Park, Burntstump Hill Country Cottage Hotel Easthorpe Street, Ruddington County House Chesterfield Road South, Mansfield Deincourt Hotel London Road, Newark DH Lawrence Heritage Centre Mansfield Road, Eastwood East Bridgford Hill Kirk Hill, East Bridgford Eastwood Hall Mansfield Road, Eastwood Elms Hotel London Road, Retford Forever Green Restaurant Ransom Wood, Southwell Road, Mansfield Full Moon Main Street, Morton, Southwell Goosedale Goosedale Lane, Bestwood Village Grange Hall Vicarage Lane, Radcliffe on Trent Hodsock Priory Blyth, Nr Worksop Holme Pierrepont Hall Holme Pierrepont, Nottingham Kelham Hall Kelham, Newark Kelham House Country Manor Hotel Main Street, Kelham, Newark Lakeside 2 Waterworks House, Mansfield Road, Arnold Langar Hall Langar Leen Valley Golf Club Wigwam Lane, Hucknall Lion Hotel 112 Bridge Street, Worksop Mansfield Manor Hotel Carr Bank, Windmill Lane, Mansfield Newark Castle Castle Gate, Newark Newark Town and District Club Ltd Barnbygate House, 35 Barnbygate, Newark Newark Town Hall Market Place, Newark Newstead Abbey -

Join the Citizens' Panel

Information services from east Valid from 1 August midlands Services 850, 852, 853 and 863 2016 Connecting your community On-line www.travelineeastmidlands.co.uk We know that your local bus services are important to you. To We’ll help you plan your journey. 850 852 keep you moving we need to be able to deliver these services in Colston Bassett Cotgrave a more efficient and effective way. 0871 200 22 33 Cropwell Bishop Owthorpe Speak to a Travel Advisor. Calls fron landlines cost To help us develop proposals on new ways of doing this we Join the Citizens’ Cropwell Basset asked you about the transport services in Nottinghamshire. You 12p per minute plus network extras. Cropwell Butler said you would like to see us: Colston Bishop Upper Saxondale Cropwell Butler • Maintain access to vital services. Panel • Increase use of community transport. Radcliffe on Trent Upper Saxondale • Make more efficient use of vehicles. Text Traveline to 84268 to receive a link to the Connections to Nottingham Radcliffe on Your views on mobile site. Scheduled bus times are shown if live times are not Based on what you told us we reviewed the local bus network Trent available. Normal data charges of your mobile operator apply. 853 863 Connections to and came up with some new proposals. We then asked you what council services Hickling Ruddington Nottingham you thought about our plans at a series of local roadshows and are really important Smartphone App The Traveline GB app is available listened to your views. to help us prioritise to download for free from your provider. -

Full Property Address Account Start Date

Property Reference Number Name (Redacted as Personal Data if Blank) Full Property Address Account Start Date 10010080460 46, Alexandra Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 7AP 01/04/2005 10010080463 Lincolnshire County Council Lincs County Council, Alexandra Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 7AP 01/04/2005 10010160350 Avc 35 Ltd The Avenue Veterinary Centre, 35, Avenue Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6TA 01/04/2005 10010615050 Neat Ideas Ltd Unit 5, Belton Lane Industrial Estate, Belton Lane, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9HN 01/04/2005 10010695200 8, Bridge Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9AE 01/04/2005 10010710010 2nd Grantham(St Wulframs) Scouts Group 2nd Grantham Scout Group, Broad Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 8AP 01/04/2005 10010720340 The Board Of Governors The Kings School The Kings School, Brook Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6PS 01/04/2005 10011150140 14, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SE 01/04/2005 10011150160 16, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SE 01/04/2005 10011150500 Grantham Conservative Club 50, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SN 01/04/2005 10011150660 The Castlegate, 69, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SJ 01/04/2005 10011290453 The Maltings Dental Practice The Maltings, Commercial Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6DE 01/04/2005 10011300272 South Kesteven District Council South Kesteven District Council, Conduit Lane, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6LQ 01/04/2005 10011810010 Dudley House School 1, Dudley Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9AA 01/04/2005 10011820020 -

Core Strategy Adopted

Rushcliffe Local Plan Rushcliffe Borough Council Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 1: Core Strategy Adopted Adopted December 2014 Local Plan Part 1: Rushcliffe Core Strategy Core Strategy Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Local Plan 3 1.3 Sustainability Appraisal 5 1.4 Habitats Regulations Assessment 5 1.5 Equality Impact Assessment 5 2. Future of Rushcliffe 6 2.1 Key Influences on the Future of Rushcliffe 6 2.2 Character of Rushcliffe 6 2.3 A Spatial Vision for Rushcliffe 10 2.4 Spatial Objectives 12 3. Delivery Strategy 15 A) Sustainable Growth Policy 1 Presumption in Favour of Sustainable Development 16 Policy 2 Climate Change 17 Policy 3 Spatial Strategy 24 Policy 4 Nottingham-Derby Green Belt 37 Policy 5 Employment Provision and Economic Development 42 Policy 6 Role of Town and Local Centres 52 Policy 7 Regeneration 57 B) Places for People 60 Policy 8 Housing Size, Mix and Choice 61 Policy 9 Gypsies, Travellers and Travelling Showpeople 68 Policy 10 Design and Enhancing Local Identity 71 Policy 11 Historic Environment 75 Policy 12 Local Services and Healthy Lifestyles 79 Policy 13 Culture, Tourism and Sport 82 Policy 14 Managing Travel Demand 85 Policy 15 Transport Infrastructure Priorities 91 C) Our Environment 96 Policy 16 Green Infrastructure, Landscape, Parks and Open Spaces 97 Policy 17 Biodiversity 103 i Local Plan Part 1: Rushcliffe Core Strategy D) Making it Happen 106 Policy 18 Infrastructure 108 Policy 19 Developer Contributions 112 Policy 20 Strategic Allocation at Melton Road, Edwalton 116 Policy 21 Strategic Allocation at North of Bingham 121 Policy 22 Strategic Allocation at Former RAF Newton 126 Policy 23 Strategic Allocation at Former Cotgrave Colliery 131 Policy 24 Strategy Allocation South of Clifton 136 Policy 25 Strategic Allocation East of Gamston/North of Tollerton 143 4.