Strategic Studies Quarterly Vol 7, No 1, Spring 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honoring Yesterday, Inspiring Tomorrow

TALK ThistleThistle TALK Art from the heart Middle Schoolers expressed themselves in creating “Postcards to the Congo,” a unique component of the City as Our Campus initiative. (See story on page 13.) Winchester Nonprofi t Org. Honoring yesterday, Thurston U.S. Postage School PAID inspiring tomorrow. Pittsburgh, PA 555 Morewood Avenue Permit No. 145 Pittsburgh, PA 15213 The evolution of WT www.winchesterthurston.org in academics, arts, and athletics in this issue: Commencement 2007 A Fond Farewell City as Our Campus Expanding minds in expanding ways Ann Peterson Refl ections on a beloved art teacher Winchester Thurston School Autumn 2007 TALK A magnifi cent showing Thistle WT's own art gallery played host in November to LUMINOUS, MAGAZINE a glittering display of 14 local and nationally recognized glass Volume 35 • Number 1 Autumn 2007 artists, including faculty members Carl Jones, Mary Martin ’88, and Tina Plaks, along with eighth-grader Red Otto. Thistletalk is published two times per year by Winchester Thurston School for alumnae/i, parents, students, and friends of the school. Letters and suggestions are welcome. Please contact the Director of Communications, Winchester Thurston School, 555 Morewood Malone Scholars Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. Editor Anne Flanagan Director of Communications fl [email protected] Assistant Editor Alison Wolfson Director of Alumnae/i Relations [email protected] Contributors David Ascheknas Alison D’Addieco John Holmes Carl Jones Mary Martin ’88 Karen Meyers ’72 Emily Sturman Allison Thompson Printing Herrmann Printing School Mission Winchester Thurston School actively engages each student in a challenging and inspiring learning process that develops the mind, motivates the passion to achieve, and cultivates the character to serve. -

HOLOCAUST DENIAL IS a FORM of HATE SPEECH Raphael Cohen

HOLOCAUST DENIAL IS A FORM OF HATE SPEECH ∗∗∗ Raphael Cohen-Almagor Introduction Recently Facebook confirmed that it has disabled a group called ‘I Hate Muslims in Oz.’ Barry Schnitt explained: “We disabled the ‘I Hate Muslims in Oz’ group… because it contained an explicit statement of hate. Where Holocaust-denial groups have done this and been reported, we’ve taken the same action”.1 Facebook distinguishes between ‘explicit statement of hate’ and Holocaust denial. Its directors believe that Holocaust denial is not hateful per se and does not therefore contravene the company’s terms of service. The terms of service say: “You will not post content that is hateful, threatening, pornographic, or that contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence”. 2 Schnitt said: “We’re always discussing and evaluating our policies on reported content, but have no plans to change this policy at this time. In addition to discussing it internally, we continue to engage with third-party experts on the issue”.3 In this short piece I wish to take issue with the assertion that Holocaust denial is not hateful per se . My aim is to show that it is, and therefore that Facebook should reconsider its position. All Internet providers and web- hosting companies whose terms of service disallow hateful messages on their servers should not host or provide forums for such hate-mongering. This is of urgent need as Holocaust denial is prevalent in Europe, the United States (USA) and across the Arab and Muslim parts of the world. Iran’s regime, under the disputed leadership of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has made questioning the Holocaust one of the centerpieces of its radical ∗ Educator, researcher and human rights activist. -

The Duquesne University School of Law News Magazine

\.....---- - ----- - ---~ The Duquesne University School of Law News Magazine DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY LAW LIBRARY APR 1 9 200t Don't Take Any Chances OnThe E MULTISTATE SPECIALIST We'll Teach You How to Win! West Coast Office New York Office East Coast Office 1247 6th Street 450 7th Avenue, Suite 3504 211 Bainbridge Street Santa Monica, CA 90401 New York, NY 10123 Philadelphia, PA 19147 (213) 459-8481 (212) 947-2525 (215) 925-41 09 Nationwide Toll Free Number: 800-315-1735 Staff EDITOR-IN-CHIEF N. S. Koerbel EXECUTIVE EDITOR Deborah L. Kutzavitch SENIOR EDITOR Annary Aytch VOL. 34, No.2 • SPRING 2001 MANAGING EDITOR LaJena D. Franks PRODUCTION EDITOR Jacquelyne S. Beckwith WEB EDITOR John Miller ASSISTANT EDITORS-IN-CHIEF A Tribute to Bridget Pelaez ... ............................................ .. .. 2 Kevin D. Coleman John E. Egers, Jr. Editorial: Learning the Secret Handshake Marianne Snodgrass by N.S. Koerbel. ... .. ......................... .. ....... ........ .................. .... 4 ASSISTANT EXECUTIVE EDITORS Margaret Barker Hate-Crimes: The Aftermath of Taylor and Baumhammers Terra Brozowski by Sanaz Raji .. ..... .. .. ....... .. .. ......... ... .. .. ... ......... ........ ........ ...... 5 Michael S. Romano Melissa A. Walls Insanity, Guilty but Mentally lll: ASSISTANT SENIOR EDITORS The Role of the Forensic Psychiatrist Debra A. Edgar by Diane Blackburn. ............... .......................... ........ ... ... ........ 7 Julie Wilson Rebecca Keating Verdone The Second Amendment and the Individual Rights Debate: ASSISTANT -

A Content Analysis of Persuasion Techniques Used on White Supremacist Websites

A Content Analysis of Persuasion Techniques Used on White Supremacist Websites Georgie Ann Weatherby, Ph.D. Gonzaga University Brian Scoggins Gonzaga University Criminal Justice Graduate I. INTRODUCTION The Internet has made it possible for people to access just about any information they could possibly want. Conversely, it has given organiza- tions a vehicle through which they can get their message out to a large audience. Hate groups have found the Internet particularly appealing, because they are able to get their uncensored message out to an unlimited number of people (ADL 2005). This is an issue that is not likely to go away. The Supreme Court has declared that the Internet is like a public square, and it is therefore unconstitutional for the government to censor websites (Reno et al. v. American Civil Liberties Union et al. 1997). Research into how hate groups use the Internet is necessary for several reasons. First, the Internet has the potential to reach more people than any other medium. Connected to that, there is no way to censor who views what, so it is unknown whom these groups are trying to target for membership. It is also important to learn what kinds of views these groups hold and what, if any, actions they are encouraging individuals to take. In addition, ongoing research is needed because both the Internet and the groups themselves are constantly changing. The research dealing with hate websites is sparse. The few studies that have been conducted have been content analyses of dozens of different hate sites. The findings indicate a wide variation in the types of sites, but the samples are so broad that no real patterns have emerged (Gerstenfeld, Grant, and Chiang 2003). -

Deafening Hate the Revival of Resistance Records

DEAFENING HATE THE REVIVAL OF RESISTANCE RECORDS "HATECORE" MUSIC LABEL: COMMERCIALIZING HATE The music is loud, fast and grating. The lyrics preach hatred, violence and white supremacy. This is "hatecore" – the music of the hate movement – newly revived thanks to the acquisition of the largest hate music record label by one of the nation’s most notorious hatemongers. Resistance Records is providing a lucrative new source of revenue for the neo-Nazi National Alliance, which ADL considers the single most dangerous organized hate group in the United States today. William Pierce, the group's leader, is the author of The Turner Diaries, a handbook for hate that was read by convicted Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh prior to his April, 1995 bombing attack. The National Alliance stands to reap thousands of dollars from the sale of white supremacist and neo-Nazi music. Resistance Records, which has had a troubled history, has been revitalized since its purchase last year by William Pierce, leader of the National Alliance. Savvy marketing and the fall 1999 purchase of a Swedish competitor have helped Pierce transform the once-floundering label into the nation’s premiere purveyor of "white power" music. Bolstering sales for Resistance Records is an Internet site devoted to the promotion of hatecore music and dissemination of hate literature. Building a Lucrative Business Selling Hate Since taking the helm of Resistance Records after wresting control of the company from a former business partner, Pierce has built the label into a lucrative business that boasts a catalogue of some 250 hatecore music titles. His purchase of Nordland Records of Sweden effectively doubled the label’s inventory to 80,000 compact discs. -

The Revisionist Clarion Oooooooooooooooooooooooooo

THE REVISIONIST CLARION OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER ABOUT HISTORICAL REVISIONISM AND THE CRISIS OF IMPERIAL POWERS oooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo TOWARDS THE DESTRUCTION OF ISRAEL AND THE ROLLING BACK OF USA ooooooooooooooooo Issue Nr. 23 Spring-Summer 2007 <revclar -at- yahoo.com.au> < http://revurevi.net > alternative archives http://vho.org/aaargh/engl/engl.html http://aaargh.com.mx/engl/engl.html ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo Ahmadinejad President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad here Monday expressed surprise over the European Union's biased approach to the historical event of holocaust. The statement was made in an exclusive interview with the Spanish television broadcast, in response to the question about holocaust. "I just raised two questions on the issue. Does EU consider questions as a crime. Today, anywhere in the world, one can raise questions about God, prophets, existence and any other issue. "Why historical events should not be clarified?" asked the chief executive. Turning to his first question, he said, "If a historical event has taken place, why do you not allow research to be conducted on it. What is the mystery behind it, given that even fresh research is conducted on definite rules of mathematics and physics.?" Ahmadinejad referred to his first question, "If such an event has actually taken place, where did it happen? Why should the Palestinian people become homeless (because of this)? "Why should Palestinian children, women and mothers be killed on streets every day for 60 years?" The president said that these innocent people losing their lives had no role in World War II. "All of them had been killed in Europe and Palestinian people were not involved in it," he added. -

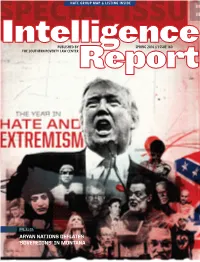

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

Chaos and Terror – Manufactured by Psychiatry

CCHR_Terror CVR R25-1.ps 10/22/04 8:25 AM Page 1 “Through the use of drugs, the skilled mind controller could first induce a hypnotic trance. Then, one of several behavior modification techniques could be employed with amplified success. In themselves, without directed suggestions, drugs affect the mind in random ways. But when drugs are combined with hypnosis, an individual can be molded and manipulated beyond his own recognition.” CHAOS AND — Walter Bowart Author, Operation Mind Control TERROR Manufactured by Psychiatry Report and recommendations on the role of psychiatry in international terrorism Published by Citizens Commission on Human Rights Established in 1969 CCHR_Terror CVR R25-2.ps 10/22/04 8:25 AM Page 2 Citizens Commission on Human Rights RAISING PUBLIC AWARENESS ducation is a vital part of any initiative to reverse becoming educated on the truth about psychiatry, and that social decline. CCHR takes this responsibility very something effective can and should be done about it. IMPORTANT NOTICE Eseriously. Through the broad dissemination of CCHR’s publications—available in 15 languages— CCHR’s Internet site, books, newsletters and other show the harmful impact of psychiatry on racism, educa- For the Reader publications, more and more patients, families, tion, women, justice, drug rehabilitation, morals, the elderly, professionals, lawmakers and countless others are religion, and many other areas. A list of these includes: he psychiatric profession purports to be know the causes or cures for any mental disorder the sole arbiter on the subject of mental or what their “treatments” specifically do to the THE REAL CRISIS—In Mental Health Today CHILD DRUGGING—Psychiatry Destroying Lives health and “diseases” of the mind. -

Transatlantica, 2 | 2012 Hate Music 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2012 Cartographies de l'Amérique / Histoires d'esclaves Hate Music Claude Chastagner Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/6075 DOI : 10.4000/transatlantica.6075 ISSN : 1765-2766 Éditeur AFEA Référence électronique Claude Chastagner, « Hate Music », Transatlantica [En ligne], 2 | 2012, mis en ligne le 02 mai 2013, consulté le 29 avril 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/6075 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.6075 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 29 avril 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Hate Music 1 Hate Music Claude Chastagner Introduction 1 A recent, extremely interesting issue of Littératures devoted to “melophobia” focuses on various forms of aversion to music as expressed in literature, from Rainer Maria Rilke to Milan Kundera, or Bret Easton Ellis (Sounac, 2012). In his exhaustive introduction, Frédéric Sounac recalls Pascal Quignard’s seminal text, La Haine de la musique (Quignard, 1996) which itself spawned numerous publications, including a similarly penned collection of essays (Coste, 2011). Quignard’s unusual suggestion is that music is a demanding, colonizing practice, an intrusive, subjugating power, almost a rape. He adds : I wonder that men wonder that those of them who like the most refined, the most complex music, who can cry when they listen to it, can at the same time be able of ferocity. Art is not the opposite of barbary. Reason is not contradictory to violence. -

Racists on the Rampage

law SKINHEADenforcement specialS I reportN AMERICA RACISTS ON THE RAMPAGE INCLUDES: Racist Skinhead Movement History • Timeline • Glossary • Portraits • Symbols • Recent Developments SKINHEADA Publication of the SouthernS IN PovertyAMERICA Law Center RACISTS ON THE RAMPAGE Racist Skinhead Movement History • Timeline • Glossary Portraits • Symbols • Recent Developments a publication of the southern poverty law center KEVIN SCANLON SKINHEADS IN AMERICA Racist skinheads are one of the potentially most dangerous radical-right threats facing law enforcement today. The products of a frequently violent and criminal subculture, these men and women, typically imbued with neo-Nazi beliefs about Jews, blacks, ho- mosexuals and others, are also notoriously difficult to track. Organized into small, mo- bile “crews” or acting individually, skinheads tend to move around frequently and often without warning, even as they network and organize across regions. For law enforcement, this poses a particular problem — responding to crimes and even conspiracies crossing multiple jurisdictions. As these extremists extend their reach across the country, it is vital that law enforcement officers who deal with them become familiar with the activities of skinheads nationwide. What follows is a general essay on the history and nature of the skinhead movement, pre- pared with the needs of law enforcement officers in mind. After that, we reprint recent reports on the contemporary skinhead movement in America, including an overview of the latest developments, portraits of 10 particularly frightening leaders, and a gallery of insignias and tattoos commonly used by racist skinheads. This booklet was prepared by the staff of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, which tracks the American radical right and also publishes the investigative magazine Intelligence Report. -

There Are No Racists Here: the Rise of Racial Extremism, When No One Is Racist

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2015 There Are No Racists Here: The Rise of Racial Extremism, When No One Is Racist Jeannine Bell Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Jeannine, "There Are No Racists Here: The Rise of Racial Extremism, When No One Is Racist" (2015). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 2410. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/2410 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THERE ARE NO RACISTS HERE: THE RISE OF RACIAL EXTREMISM, WHEN NO ONE IS RACIST Jeannine Bell* ABSTRACT At first glance hate murders appear wholly anachronistic in post-racial America. This Article suggests otherwise. The Article begins by analyzing the periodic ex- pansions of the Supreme Court's interpretation of the protection for racist expres- sion in First Amendment doctrine. The Article then contextualizes the case law by providing evidence of how the First Amendment works on the ground in two separate areas -the enforcement of hate crime law and on university campuses that enact speech codes. In these areas, those using racist expression receive full protec- tion for their beliefs. -

Neurodevelopmental and Psychosocial Risk Factors in Serial Killers and Mass Murderers

Allely, Clare S., Minnis, Helen, Thompson, Lucy, Wilson, Philip, and Gillberg, Christopher (2014) Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial risk factors in serial killers and mass murderers. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19 (3). pp. 288-301. ISSN 1359-1789 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/93426/ Deposited on: 23 June 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Aggression and Violent Behavior 19 (2014) 288–301 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aggression and Violent Behavior Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial risk factors in serial killers and mass murderers Clare S. Allely a, Helen Minnis a,⁎,LucyThompsona, Philip Wilson b, Christopher Gillberg c a Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, RHSC Yorkhill, Glasgow G3 8SJ, Scotland, United Kingdom b Centre for Rural Health, University of Aberdeen, The Centre for Health Science, Old Perth Road, Inverness IV2 3JH, Scotland, United Kingdom c Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Multiple and serial murders are rare events that have a very profound societal impact. We have conducted a Received 11 July 2013 systematic review, following PRISMA guidelines, of both the peer reviewed literature and of journalistic and Received in revised form 20 February 2014 legal sources regarding mass and serial killings. Our findings tentatively indicate that these extreme forms of vi- Accepted 8 April 2014 olence may be a result of a highly complex interaction of biological, psychological and sociological factors and Available online 18 April 2014 that, potentially, a significant proportion of mass or serial killers may have had neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder or head injury.