Vol. 17, Spring 2002 at Pg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the Year Ended March

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1994-95 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($87,902,805) Temporary Help Services ($1,329,292): Management Board Secretariat, 1,220,010; Accounts under $50,000—109,282. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($196,635): Environment and Energy, 196,635. Employee Benefits ($13,866,524) Payments for Canada Pension Plan, 1 ,594,486; Dental Plan, 95 1 ,332; Employer Health Tax, 1 ,702,083; Group Life Insurance, 170,970; Long Term Income Protection, 1,028,176; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 1,016,690; Unemployment Insurance, 3,017,224; Unfunded Liability— Public Service Pension Fund, 1,024,574. Other Benefits: Attendance Gratuities, 401,716; Death Benefits, 18,660; Early Retirement Incentive, 467,244; Maternity/Parental/Adoption Leave Allowances, 530,045; Severance Pay, 1,494,057; Miscellaneous Benefits, 51,035. Workers' Compensation Board, 315,097. Payments to Other Ministries ($152,141): Accounts under $50,000—152,141. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($69,006): Accounts under $50,000—69,006. Travelling Expenses ($3,859,979) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 7,002; P. Klopp, 3,765; R. Burak, 9,912; W.R. Allen, 13,155; D.K. Alles, 16,276; P.M. Angus, 23,969; D. Beattie, 12,681; A. Bierworth, 14,510; J.L. Cushing, 12,125; L.L. Davies, 11,521; P. Dick, 16,999; E.J. Dickson, 11,231; R.C. Donais, 10,703; J.R. Drynan, 10,277; R. Dunlop, 10,662; JJ. Gardner, 43,319; C.L. Goubau, 12,096; N. Harris, 12,593; F.R Hayward, 26,910; M. -

Magazine W 0 Men 0 F Colour

MAGAZINE B y W 0 MEN 0 F COLOUR YOKO !CHINO BEYERL Y SALMON Marva Jackson Zanana Akande THE VERTICAL MOSAIC IN CANADIAN THE FEMINIST MOVEMENT IN LATIN PERCEPTIONS OF VISIBLE MINORITIES AMERICA: BALANCE AND PERSPECTIVE Susan Korab Luz Helena Sanchez Gomez THE JESUITS AND THE PEACE MOVEMENT CANADA'S NATIVE PEOPLE WOMEN'S ROLE IN THE INT'L ARENA Susan Daybutch Hare Margarita Papandreou Denied personhood, and so the right to the to perform as they thought they should; push- vote until 1921, women in Canada are lateco- ing them to legislate social reform which pro- mers to the political scene. Women had burst tected the powerless, provide for those with- into the political arena after-many years of out, and established services to respond to collec~ive opposition to the 'status quo. But changing social patterns. the aggressiveness and determination which Such political roles, though too often un- characterized their successful struggle to a- recognized, or acknowledged as only secon- chieve their political rights has not spanned dary, are as necessary to politics as the front the years to achieve any more than women's line politicians. token representation in the legislative assem- Gradually, but steadily, more women are blies of our municipalities, provinces and concluding that their ,causes might be best country. championed by women who share their inter- Their goal, the franchise, achieved, women's ests; or that it might be more expedient to collective aggression disipated; wrapped in carry the torch rather than only to light it and the security of the possible, they turned their hope that it will be used to illuminate the attention to moral questions. -

Women's Suffrage in Ontario the Beginning of Women’S Suffrage Movements

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY an educational resource OF ONTARIO MESSAGE TO TEACHERS This educational resource was developed to compliment the documentary Women Should Vote: A Short History of how Women Won the Franchise in Ontario (www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/ about-ontarios-parliament/womens-suffrage-ontario), A NOTE ON LANGUAGE which tells the story of the struggle for women’s Some historical terms used in this resource are suffrage in Ontario at the turn of the 20th century. no longer in common use. First Nations peoples in Canada were initially called “Indians” by colonial It invites students to deepen their understanding of Europeans. This term is no longer used, though gender equality and democracy through examining and “Status Indian” is still a legal definition and is analyzing the suffrage movement, and facilitates mentioned throughout this guide. “Status Indian” engaging discussions and activities. Students will does not include all Indigenous peoples – for examine issues of identity, equity, activism and example, Métis and Inuit are excluded (see the justice in historical and contemporary contexts. Glossary on Page 22 for more information). CONTENTS The Suffrage Movement in Running the Good Race ............. 9 Glossary ......................... 22 Ontario: Votes for Women ............ 2 Indigenous Suffrage ............... 11 Activities The Beginning of Women’s Clues from the Archives Suffrage Movements ................ 3 Final Reflections ..................13 (Designed for Grades 8-12) .......23 Should I Support the Vote? The Long Road Timeline of Women’s Suffrage (Designed for Grades 4-7) ........24 to Women’s Suffrage ................ 4 in Ontario and Canada ............. 14 Our Rights Today ................25 A New Century ..................... 5 Feature Figures Appendix A ...................... -

The Informer

Summer 2018 Table of Contents Welcome, former parliamentarians! Below is a list of what you’ll find in the latest issue of The InFormer. Meet the team: Introducing our interns/ 2 In conversation with Haley Shanoff/ 3 In conversation with His Honour Henry Jackman/ 5 In conversation with Zanana Akande/ 7 Two special days/ 10 Educational efforts/ 11 Russian cannons/ 12 In conversation with Floyd Laughren/ 13 Discover: Ontario beer/16 Ale trails/ 17 Discover: Ontario wine/ 18 Ontario’s treasures/ 19 The artists of Queen’s Park/ 20 In loving memory of Walter Pitman/ 21 1 InFormer Team Meet the Interns Summer 2018 Victoria Shariati is a journalist and Zena Salem is a multilingual journalism academic researcher currently student at Ryerson University, minoring completing a journalism degree at in French, and Entrepreneurship and Ryerson University. She is minoring in Innovation. Post-graduation, she aims to both history and politics. pursue a master’s degree in international law and policy. With a keen interest in politics and foreign affairs, Victoria hopes to earn In addition to being passionate about a mastor’s degree in a field that would international journalism, her work help her explore the intricacies of focuses on social issues, law, politics, Canadian public and foreign policy and religion and culture and human rights. international law. Zena aspires to be a news anchor and Victoria began working with the Ontario journalist, covering events and issues Association of Former Parliamentarians that target marginalized groups, law and in May of 2018. politics -both locally and internationally. 2 Inspiring People In conversation with Haley Shanoff Curator of The Gathering Place, Queen’s Park What is your background, as related to the world of art? I have an undergraduate degree in history and a master’s in museum studies, so my focus was always more on history than on art. -

Legal Aid Ontario Advisory Committee on Legal Services to the Black Community

Fact sheet Legal Aid Ontario advisory committee on legal services to the Black community LAO is working with an advisory committee to establish a new, community-based organization to deliver legal services to Black Ontarians who are experiencing anti-Black racism. The members of the advisory committee were not involved in the dispute resolution process between LAO and ACLC. Rather, they are advising LAO on how to best meet the needs the Black community going forward. The members of the advisory committee are: as a cabinet minister in Canada. A New Democratic Idil Abdillahi MLA from 1990 to 1994, she represented the downtown Idil Abdillahi is an assistant professor at Ryerson Toronto riding of St. Andrew-St. Patrick and served as a University School of Social Work. Her research interests cabinet minister in the government of Bob Rae. are grounded in the Black Radical Tradition, anti-Black racism and Black feminist thought, all of which are After leaving politics, Ms. Akande served as president informed by the struggles and active resistance of Black of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations, Canadian communities locally and internationally. She has written Alliance of Black Educators and Toronto Child Abuse numerous peer-reviewed publications and book chapters Centre. She worked with other community-based centering on themes of Blackness/anti-Blackness, Black groups including the United Way of Greater Toronto, studies in policy, poverty and the advancement of the the Family Services Association and the Elizabeth Fry Black liberation at the intersection of social services. Society. She was the recipient of the African Canadian Achievement Award for Education and the Award of Outside of her work in the academy, she is Board Chair Distinction from the Congress of Black Women. -

Tsotoronto Symphony Orchestra

Toronto 11.12 Symphony ANNUAL Orchestra REPORT tso Peter Oundjian, Music Director 11.12 90 th Season Big Number. Bold Season. From our Music Director Ninety is an interesting age for an orchestra. In the context of a lifetime, the TSO has had a relationship with several generations of Torontonians and guest artists. Within the context of the composers who inspire us and their repertoire which has truly stood the test of time, 90 is quite young. At 90, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra presented a landmark season of bold musical experiences which continue to connect, transcend, and enrich our community. We are a vibrant orchestra, fresh at 90, and powered by the traditions of greatness from which we draw our repertoire. Our commitment to creating art and refreshing our art form was reflected in the celebration of new music and composers throughout the 2011.2012 programme, in our New Creations Festival, and in welcoming 28 débuting artists during the 90th season. We are passionate about enriching our community through art and the power of music, as evidenced so clearly by the major 90th season Residencies featuring three of the greatest artists performing today. I am indebted to, and inspired by, the talented musicians of the TSO, who every day share their passion and commitment towards exceptional orchestral performances. I thank you, the audience, for your enthusiasm in these live concert experiences. Sincerely, Peter Oundjian MUSIC DIRECTOR 3 Chair’s Message The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s 90th season was an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of the organization and to present an extraordinary season of stellar guest artists, remarkable artistic programming, and special celebrations, including our major fundraising event, Celebrate 90 , which was a landmark for the organization. -

Multiculturalism and the De-Politicization of Blackness in Canada: the Case of Flow 93.5 Fm

MULTICULTURALISM AND THE DE-POLITICIZATION OF BLACKNESS IN CANADA: THE CASE OF FLOW 93.5 FM by Kisrene McKenzie A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto © Copyright by Kisrene McKenzie 2009 MULTICULTURALISM AND THE DE-POLITICIZATION OF BLACKNESS IN CANADA: THE CASE OF FLOW 93.5 FM Master of Arts 2009 Kisrene McKenzie Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis presents a case study of Canada‟s first Black owned radio station, FLOW 93.5 FM, to demonstrate how official multiculturalism, in its formulation and implementation, negates Canada‟s history of slavery and racial inequality. As a response to diversity, multiculturalism shifts the focus away from racial inequality to cultural difference. Consequently, Black self-determination is unauthorized. By investigating FLOW‟s radio license applications, programming and advertisements, this thesis reveals just how the vision of a Black focus radio station dissolved in order to fit the practical and ideological framework of multiculturalism so that Blackness could be easily commodified. This thesis concludes that FLOW is not a Black radio station but instead is a multicultural radio station – one that specifically markets a de-politicized Blackness. As a result, multiculturalism poses serious consequences for imagining and engaging with Blackness as a politics that may address the needs of Black communities in Canada. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I extend my deepest gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sherene Razack, for her guidance, constant support, encouragement and initial interest in my thesis topic. -

What Happened to Antiracist Education? the 1993 Antiracism and Ethnocultural Equity Educational Reform in Ontario School Boards

What Happened to Antiracist Education? The 1993 Antiracism and Ethnocultural Equity Educational Reform in Ontario School Boards Douglas Tateishi Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate degree Faculty of Education University of Ottawa © Douglas Tateishi, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 WHAT HAPPENED TO ANTIRACIST EDUCATION? ii Abstract This research uses an antiracism theoretical framework, arising from Stanley’s (2011, 2014) anti-essentialist antiracism and Dei’s (1996) anti-racism praxis, to focus on the four documents that comprised the Ontario Ministry of Education’s 1993 Antiracism and Ethnocultural Equity initiative (the initiative). The initiative required school boards to develop and implement policies to identify and eliminate racisms within their systems and schools. I used a methodology of constructivist grounded theory to trace the origins and content of the initiative through the lens of my 44-years of lived experience, during which I was a teacher, principal, superintendent, associate director of education, and ministry education officer. This thesis poses the overarching question: What happened to antiracism and ethnocultural equity? I find that although the initiative was a genuine antiracism project, it was destined to fail due to certain deficiencies. I conclude it had two critical deficiencies. First, it did not consider the four discrete cultures located in school boards (made up of supervisory officers, trustees, principals and teachers). Second, it did not provide these cultures with suitable pressures and supports to generate the individual and organizational changes envisioned. Finally I consider what the Ministry would need to do for such an antiracism reform to succeed? I argue systemic policy reform must be based on what I call strategic antiracist education. -

The Social Justice Community in Toronto

The Social Justice Community in Toronto A Report for the George Cedric Metcalf Charitable Foundation Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 3 Part I: Challenges for Urban Social Justice Movements: Neoliberal Urbanism, the Canadian City and Toronto.............. 4 Part II: The Social Justice Community in Toronto...........................16 Appendix 1: The Centre for Social Justice Mission Statement ......23 Appendix 2: Outreach Survey Letter to Toronto Social Justice Organizations .....................................25 Appendix 3: CSJ News Letter Sample ...........................................28 Appendix 4: Groups Struggling Against Poverty and Inequality in Ontario .........................................................39 Appendix 5: Get Social Campaign .................................................46 Appendix 6: Factsheets on Poverty................................................48 Appendix 7: Toronto Social Justice Groups Data Base .................72 3 The Social Justice Community in Toronto A Report for the George Cedric Metcalf Charitable Foundation Centre for Social Justice INTRODUCTION This report has two main parts. The first is an analytical discussion paper prepared at the conclusion of the work to assess our understanding of urban politics today, the challenges for urban social justice movements and community organizations, and the specific contexts for some of these issues in Toronto. It is part of our final evaluation allowing us to focus our research and educational efforts, after a lengthy period of restructuring, and how we might develop CSJ work in the future. The second part reports on the specific work for the grant. It includes a report on the specific tasks that were set to aid social justice community building, the fact sheets developed and two inventories on social justice work in Toronto. It also provides a review of the work that the CSJ has done that has overlapped with the terms of reference set out in the work with the Metcalfe Foundation. -

2019 Africian Canadian Calendar Final.Indd

Maria Rizzo, Chair of the Board the of Chair Rizzo, Maria Education of Director McGuckin, Rory Psalm 23: 1-4 23: Psalm sake. For His Name’s Name’s His For in right paths paths right in soul. He leads me me leads He soul. He restores my my restores He beside still waters; waters; still beside He leads me me leads He pastures; pastures; lie down in green green in down lie He makes me me makes He I shall not want. want. not shall I my Shepherd, Shepherd, my The Lord is is Lord The CANADIAN HERITAGE CANADIAN FRICAN A 2019 CELEBRATING TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD TRUSTEES 2018 - 2019 Wards 1. Joseph Martino 416-512-3401 2. Markus de Domenico 416-512-3402 3. Ida Li Preti 416-512-3403 4. Teresa Lubinski 416-512-3404 5. Maria Rizzo 416-512-3405 6. Frank D’Amico 416-512-3406 7. Mike Del Grande, Vice Chair 416-512-3407 8. Garry Tanuan 416-512-3408 9. Norm Di Pasquale 416-512-3409 10. Daniel Di Giorgio 416-512-3410 11. Angela Kennedy 416-512-3411 12. Nancy Crawford 416-512-3412 Taylor Dallin, Student Trustee 416-512-3413 Joel Ndongmi, Student Trustee 416-512-3417 Rory McGuckin, Director of Education Maria Rizzo, Chair of the Board Toronto Catholic District School Board 80 Sheppard Ave. E., Toronto, Ontario M2N 6E8 416-222-8282 . www.tcdsb.org We transform the world through witness, faith, innovation and action. ON THE COVER... VIOLA DESMOND FIRST TIME A CANADIAN WOMAN IS ON A COUNTRY’S CURRENCY The new $10 bank note unveiled in Halifax features the portrait of Viola Desmond. -

Freeland Needs to Share Financial Plans, Says PBO Yves Giroux

Benefit of Canada’s public doubt rarely safety, national given to security must prioritize and Indigenous Gwynne confront violent peoples Dyer white supremacy By Rose LeMay p. 5 p.12 By Huda Mukbil p. 4 Michael Harris p.14 THIRTY-SECOND YEAR, NO. 1772 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2020 $5.00 News News News ‘Six systemic crises’ MPs, Taiwanese confronting Canada Canada needs a envoy highlight right now, and opportunities politicians, policy- to strengthen makers, health- new ‘fiscal anchor,’ care professionals relations need ‘systems between thinking’ to tackle Freeland needs to Taiwan, Canada them, says public amid COVID-19 policy expert share financial plans, fallout, China BY MIKE LAPOINTE tensions oliticians, policy-makers, and BY MIKE LAPOINTE Phealth-care professionals says PBO Yves Giroux have been too busy focusing on t a time of escalating tensions beating back the pandemic and between Canada and China trying to ensure Canadians are A in the midst of an ongoing U.S.- Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux says he’s found it ‘much China trade war, a number of MPs Continued on page 20 more difficult to get information out of the minister’s office’ since Parliament and Taipei’s economic and cultural office representative in Canada say returned with Chrystia Freeland in charge of the nation’s finances. this is a “massive opportunity” for moves toward closer cooperation between this country and Tai- News Deputy Prime Minister wan—particularly in light of what’s and Finance required to rebuild our country’s Minister Chrystia battered economy in the months Senators zip lips Freeland, and years to come. -

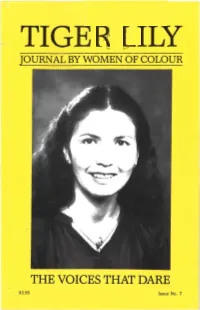

The Voices That Dare

v ....... THE VOICES THAT DARE $3.95 Issue No. 7 THE VOICES THAT DARE ________ TIGER LILY ________ Journal by Women of Colour Publisher I Editor-in-Chief Ann Wallace Editorial Committee Zanana Akande, Susan Korah, Monicc;i Riutort, Karen 'fyrell Contributing Writers Zanana Akande, Jeannette Armstrong, Ramabai Espinet, Alice French, Z. Nelly Martinez, Arun Mukherjee, Angela Lawrence, Sonya C. Wall, Ivy Williams Production Duo Productions Ltd. Business Manager Gloria Fallick Advisory Board Gay Allison, Glace Lawrence, Ana Mendez, Arun Mukherjee, Beverly Salmon, Leslie Sanders, Anita Shilton Photo Credits Cover Photo - Hugo Redivo Tiger Lily journal is published by Earthtone Women's Magazine (Ontario) Inc. P.O. Box 756, Stratford, Ontario NSA 4AO. ISSN 0-832-9199-07. Authors retain copyright, 1990. All Rights reserved. Unsolicited manuscripts or artwork should include a SASE. Printed and Bound in Canada. --------CONTENTS ________ 4 From the Publisher's Desk PROFILE: 6 Jeannette Armstrong: A Native Writer and Administrator Sonya C. Wall POETRY: 10 Bre9th Tracks Jeannette Armstrong INUIT BIOGRAPHY: 18 My Name is Masak Alice French ESSAY: 23 The Third World in the Dominant Western Cinema Arun Mukherjee EDUCATION 32 Fran Endicott, Board Trustee Zanana Akande FICTION: 35 Because I Could Not Stop for Death Ramabai Espinet HEALTH: 40 After the Door Has Been Opened Ivy Williams ESSAY: 49 Isabel Allende's - The House of the Spirits The Emergence of a Feminine Space Z. Nelly Martinez BOOK REVIEW: 58 Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women Angela Lawrence ____ FROM THE PUBLISHER'S DESK ____ The Voices That Dare The role of the storyteller is critical in all societies.