Budd Revisited - Gambling in Great Britain 15 Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gambling Commission Submission to the Australian Online Gambling Review

Gambling Commission submission to the Australian online gambling review Inquiry by Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform into Interactive Gambling – Further Review of Internet Gaming and Wagering June 2011 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The Gambling Commission 3 3 The Gambling Act 2005 4 4 Remote gambling 5 5 The Gambling Act 2005: Definition of gambling 5 6 The Gambling Act 2005: Definition of remote gambling 5 7 Licence Conditions and Codes of Practice 5 8 Remote technical standards 6 9 Betting exchanges 7 10 Developments in remote gambling 7 11 Betting Integrity 10 12 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This document provides information in response to questions outlined in the 17 May 2011 annoucement by the Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform on the further review of internet gaming and wagering. 1.2 The responses to the questions in the paper are covered throughout this document and the following highlights the sections in which the answers can be found: (a) the recent growth in interactive sports betting and the changes in online wagering due to new technologies – covered in section 10 (b) the development of new technologies, including mobile phone and interactive television, that increase the risk and incidence of problem gambling – covered in section 10 (c) the relative regulatory frameworks of online and non-online gambling – covered in sections 2 – 8 (d) inducements to bet on sporting events online – covered in section 7.3 (e) The risk of match-fixing in sports as a result of the types of bets available online, and whether -

University of Surrey Discussion Papers in Economics By

råáp=== = = ======råáîÉêëáíó=çÑ=pìêêÉó Discussion Papers in Economics THE DISSENT VOTING BEHAVIOUR OF BANK OF ENGLAND MPC MEMBERS By Christopher Spencer (University of Surrey) DP 03/06 Department of Economics University of Surrey Guildford Surrey GU2 7XH, UK Telephone +44 (0)1483 689380 Facsimile +44 (0)1483 689548 Web www.econ.surrey.ac.uk ISSN: 1749-5075 The Dissent Voting Behaviour of Bank of England MPC Members∗ Christopher Spencer† Department of Economics, University of Surrey Abstract I examine the propensity of Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee (BoEMPC) members to cast dissenting votes. In particular, I compare the type and frequency of dissenting votes cast by so- called insiders (members of the committee chosen from within the ranks of bank staff)andoutsiders (committee members chosen from outside the ranks of bank staff). Significant differences in the dissent voting behaviour associated with these groups is evidenced. Outsiders are significantly more likely to dissent than insiders; however, whereas outsiders tend to dissent on the side of monetary ease, insiders do so on the side of monetary tightness. I also seek to rationalise why such differences might arise, and in particular, why BoEMPC members might be incentivised to dissent. Amongst other factors, the impact of career backgrounds on dissent voting is examined. Estimates from logit analysis suggest that the effect of career backgrounds is negligible. Keywords: Monetary Policy Committee, insiders, outsiders, dissent voting, career backgrounds, ap- pointment procedures. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Relationship to the Literature 2 3 Rationalising Dissent Amongst Insiders and Outsiders - Some Priors 3 3.1CareerIncentives........................................... 4 3.2CareerBackgrounds........................................ -

Letter to the Gambling Commission

Sarah Gardener Committee of Advertising Practice Executive Director Castle House, 37-45 Paul Street Gambling Commission London EC2A 4LS Telephone 020 7492 2200 Email [email protected] [email protected] www.cap.org.uk 22 October 2020 Dear Sarah Update on CAP and BCAP’s response to the GambleAware research I’m pleased to inform you that CAP and BCAP have today published a consultation proposing significant new restrictions on the creative content of gambling and lotteries advertising. This is an important step in meeting our commitment to respond in full to the emerging findings of the GambleAware research and ensuring that the UK Advertising Codes remain up to date with the evidence base in protecting under-18s and other vulnerable groups. The consultation will run until 22 January and we hope to announce the outcome in the first half of 2021, introducing any changes to the Codes by the end of the year. As well as introducing the consultation, this letter comments on several of the GambleAware recommendations directed at industry or where we have been carrying out policy and enforcement activity separate to the consultation. You’ll be aware that several of the recommendations have been carried over from GambleAware’s Interim Synthesis Report, published in July 2019 Restrictions on adverting volumes We address in the consultation the GambleAware question of whether to strengthen the existing policy (CAP’s ‘25% test’) on where, in non-broadcast media, it is acceptable to place a gambling ad. But, we also note the separate recommendation, directed at industry, to reduce the overall volume of gambling advertising and marketing messages reaching children, young people and vulnerable adults. -

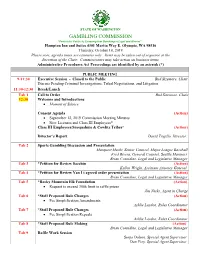

October Packet -Public.Pdf

STATE OF WASHINGTON GAMBLING COMMISSION “Protect the Public by Ensuring that Gambling is Legal and Honest” Hampton Inn and Suites 4301 Martin Way E. Olympia, WA 98516 Thursday, October 10, 2019 Please note, agenda times are estimates only. Items may be taken out of sequence at the discretion of the Chair. Commissioners may take action on business items. Administrative Procedures Act Proceedings are identified by an asterisk (*) PUBLIC MEETING 9-11:30 Executive Session - Closed to the Public Bud Sizemore, Chair Discuss Pending Criminal Investigations, Tribal Negotiations, and Litigation 11:30-12:30 Break/Lunch Tab 1 Call to Order Bud Sizemore, Chair 12:30 Welcome and Introductions • Moment of Silence Consent Agenda (Action) • September 12, 2019 Commission Meeting Minutes • New Licenses and Class III Employees* Class III Employees/Snoqualmie & Cowlitz Tribes* (Action) Director’s Report David Trujillo, Director Tab 2 Sports Gambling Discussion and Presentation Marquest Meeks, Senior Counsel, Major League Baseball Fred Rivera, General Counsel, Seattle Mariners Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 3 *Petition for Review Saechin (Action) Kellen Wright, Assistant Attorney General Tab 4 *Petition for Review Yan Li agreed order presentation (Action) Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 5 *Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (Action) • Request to exceed 300k limit in raffle prizes Jim Nicks, Agent in Charge Tab 6 *Staff Proposed Rule Changes (Action) • Fee Simplification Amendments Ashlie Laydon, Rules Coordinator Tab 7 *Staff Proposed Rule Changes (Action) • Fee Simplification Repeals Ashlie Laydon, Rules Coordinator Tab 8 *Staff Proposed Rule Making (Action) Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 9 Raffle Work Session Sonja Dolson, Special Agent Supervisor Dan Frey, Special Agent Supervisor Public Comment Adjourn Upon advance request, the Commission will pursue reasonable accommodations to enable persons with disabilities to attend Commission meetings. -

Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions Group Of

Birmingham, 24 January 2019 T-MC(2019)3uk Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions Group of Copenhagen – Network of National Platforms National Platform fact sheet UNITED KINGDOM 1. Administrative issues / State of progress State of Progress Operational. Comprises the Sports Betting Intelligence Unit (SBIU) which was formed in 2010 and the Sports betting Integrity Forum (SBIF) which was formed in 2012. Legal Status No basis in law. Actions deliverable through the UK Anti-Corruption Plan1 and Sports and Sport Betting Integrity Plan (The Plan): The Sports Betting Integrity Forum (SBIF) is responsible for delivery of The Plan. Betting Operators are obliged to report suspicious activity to the SBIU, as part of the License Conditions and Codes (condition 15.1) if it relates to or they suspect may relate to the commission of an offence under the Gambling Act (2005), may lead the Commission to take action to void a bet or is a breach of a Sports Governing Bodies betting rules. Responsible Secretariat The SBIU is part of the wider Commission Betting Integrity Programme. The Commission is an independent non-departmental public body (NDPB) sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The Commission’s work is funded by fees set by DCMS and paid by the organisations and individuals we license The secretariat of the SBIF is undertaken by the Gambling Commission. Contact persons Lorraine Pearman, [email protected]; + 44 7852 429 168 Organizational form and composition of NP (bodies/entities) The Sports Betting Intelligence Unit (SBIU) is a unit within the Gambling Commission which manages reports of betting-related corruption. -

Gambling Industry Code for Socially Responsible Advertising

Gambling Industry Code for Socially Responsible Advertising 2020 September 6th Edition, GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6th Edition October 2020 CONTENTS Introduction paras 1-5 Origins and role of the Industry Code paras 6-11 Legislative, licensing & regulatory context paras 12-18 General principles paras 19-20 Social Responsibility messaging paras 21-25 Inclusion of ‘BeGambleAware’ in advertising paras 26-30 Television advertising – watershed paras 31-40 Television advertising – responsible gambling messaging paras 41-43 Television advertising – text & subtitling para 44 Radio messaging para 45 18+ messaging para 46 Online banner advertising para 47 Sports’ sponsorship para 48 Sponsorship of television programmes paras 49-51 Social media – marketing paras 52-55 Promoting consumer awareness parags 56-57 Search activity paras 58 -60 Affiliate activity paras 61-62 Coverage of the Industry Code paras 63-66 Monitoring and review paras 67-68 Checklist para 69/Annex A and Annex B GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6th Edition October 2020 GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY ORIGINS AND ROLE OF THE INDUSTRY CODE RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6. The Gambling Act 2005 amended some of 1. The Industry Code for Socially Responsible the longstanding advertising restrictions. Advertising (the ‘Industry Code’) was For example, for the first time it permitted originally introduced on 1 September 2007. television advertising for all forms of gambling. Its aim was to provide gambling operators Before that only very few types of gambling with a range of measures that would enhance such as bingo and the National Lottery the social responsibility of their advertising could be advertised in this way. -

The Political Economy of Tax Policy

IFS The Political Economy of Tax Policy James Alt Ian Preston Luke Sibieta Prepared for the Report of a Commission on Reforming the Tax System for the 21st Century, Chaired by Sir James Mirrlees www.ifs.org.uk/mirrleesreview The Institute for Fiscal Studies Full Report to be published by Oxford University Press The Political Economy of Tax Policy1 Final Draft for Mirrlees Review 12 March 2008 Do not cite or quote without the authors’ permission Professor James Alt, Harvard University Professor Ian Preston, University College London and the Institute for Fiscal Studies Luke Sibieta, Institute for Fiscal Studies 1 The authors thank Stuart Adam, Lucy Barnes, Tim Besley, Ian Brimicombe, Alan Budd, Judith Freedman, Rachel Griffith, James Hines, Paul Johnson, Alison Post, James Poterba, Christopher Sanger, Guido Tabellini, Christopher Wales and conference participants in Cambridge for their helpful comments and suggestions 1 Executive Summary This chapter reviews major changes in British tax-setting institutions in the last quarter century and highlights four key points about the politics of tax policy, which are summarised below. The chapter also makes policy recommendations, such as for improving scrutiny and parliamentary accountability; these are also summarised below. A “passive” movement to the right The chapter analyses whether changes in voter preferences and strategic party positioning could explain declines in statutory rates of income tax. What we discover is that electoral support has moved to the right, though voters seem to have followed rather than led the changing content of party manifestos. Voters have always favoured redistribution, particularly from those with the highest incomes to those with the lowest incomes. -

The Global Financial Crisis – Why Didn't Anybody Notice?

8 THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS – WHY DIDN’T ANYBODY NOTICE? The Global Financial Crisis – Why Didn’t Anybody Notice? On 17 June 2009, a group of leading academics, economics journalists, politicians, civil servants, and other practitioners met at the British Academy for a round-table discussion of the current financial crisis. The question under discussion in this British Academy Forum had been framed by Her Majesty The Queen on a visit to the London School of Economics in November 2008, when she had asked: if these things were so large, how come everyone missed them? A purpose of the Forum was to provide the basis of an ‘unofficial command paper’ that attempted to answer this question. The discussion inevitably ranged more widely – touching on the social fall-out of the crisis, and including a plea for a greater emphasis on the teaching of economic history in universities. But it was with The Queen’s question in mind that the two convenors of the meeting, Professor Tim Besley FBA and Professor Peter Hennessy FBA , subsequently drafted a letter summarising the discussion: it was sent to Buckingham Palace on 22 July. MADAM, When Your Majesty visited the London School of Economics last November, you quite rightly asked: why had nobody noticed that the credit crunch was on its way? The British Academy convened a forum on 17 June 2009 to debate your question, with contributions from a range of experts from business, the City, its regulators, academia, and government. This letter summarises the views of the participants and the factors that they cited in our discussion, and we hope that it offers an answer to your question. -

Gambling Behaviour in England & Scotland

Gambling behaviour in England & Scotland Headline findings from the Health Survey for England 2012 and Scottish Health Survey 2012 Authors: Carla Seabury and Heather Wardle Date: 15/04/2014 Prepared for: The Gambling Commission Acknowledgements We would like to thank all those colleagues who contributed to creating the combined Health Survey for England (HSE) / Scottish Health Survey (SHeS) dataset and this report. In particular we would like to thank: • Our principal Data Manager Joan Corbett, whose hard work and advice was vital in preparing and creating the combined dataset. • Colleagues Catherine Bromley and Cathy Coshall who helped with advice and support on data issues when needed. • Statisticians, Christos Byron and Kevin Pickering who calculated and produced the weights to calibrate the data. • Other colleagues from the HSE and SHeS teams at NatCen, who provided documents and advice when requested. In addition, our thanks are due staff at the Gambling Commission, in particular that of Fiona Phillip, Marc Hannis and Rebekah Eden. Finally, we thank all the participants who took part in each survey and made this report possible. Carla Seabury, Heather Wardle Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................ 3 Purpose ..............................................................................................................3 Background ..............................................................................................................3 Report conventions .........................................................................................................4 -

Jersey Gambling Commission Annual Report and Accounts 2020

2020 Jersey Gambling Commission Annual Report and Accounts R.129/2021 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Chief Executive’s Statement ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Board.......................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Executive ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Licensing and Regulation ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Approach to Regulation ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Regulatory Review 2020 ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) .................................................... 8 Social Responsibility .................................................................................................................................................................. -

The Geography of Gambling Premises in Britain

THE GEOGRAPHY OF GAMBLING PREMISES IN BRITAIN Summary: Nearly three-quarters of consumers say that they would not want gambling premises on their ‘ideal’ high street, and there are concerns from those with lived experience of gambling harms that such venues “prey on those that can’t afford it and have taken over streets in rundown areas and towns”. With the UK Government’s commitment to ‘level-up’ the country, it is therefore important to understand the geography of gambling premises throughout Britain and the extent to which it matches other types of geographical inequalities between areas. The Gambling Commission reports that as of March 2020 there were still over 10,000 gambling premises in Britain – more than the number of stores (9,968) run by the eight largest supermarket chains in the country. This report introduces various academic and grey literature on the geography of gambling premises and also presents new analyses of gambling licensing data from local authorities. We find that: • A long-running trend of gambling premises being more common in deprived areas persists in Britain. As of November 2020, 21% of gambling premises were based within the most deprived decile of areas in the country, compared to just 2% in the least deprived decile. By way of comparison, just 10% of supermarkets were located in the most deprived decile and 7% were in the least deprived decile. • The relationship with deprivation is stronger for ‘family entertainment centres’ (FECs, also commonly called ‘amusement arcades’) – with 34% of such venues located in the most deprived decile. Bingo venues and adult gaming centres (AGCs) also have a strong relationship with deprivation, while it is slightly weaker (but still significant) for casinos and betting shops. -

Lydia Thomas, Producer, BBC Radio 4 – Written Evidence (GAM0004)

Lydia Thomas, Producer, BBC Radio 4 – Written evidence (GAM0004) I’m a Journalist on BBC Radio 4’s consumer affairs programme, You and Yours. For the past 4 years I have been reporting on the gambling industry for You and Yours and produced a Radio 4 documentary called My Name Is Katie on the subject. I am not personally affected nor do I have a moral issue with gambling. However, I believe that the gambling environment in the UK isn’t safe or fair for consumers. The evidence I want to bring to the Committee’s attention is based on what our listeners have told me about their dealings with online gambling firms in particular. Most of my answers relate to Questions 1-3. But first I’d like to summarise the main cases I have been reporting on and illustrate how the current laws and regulations do not protect customers. Although there are regulations in place that require companies to; engage with customers who display signs of problem gambling, and to analyse the data they have on customers to be proactive and protect customers. In my experience this does not happen. In fact it is the total opposite, and the gambling companies are using this data on their customers to encourage them to spend more than they can afford. For example, many companies offer VIP programmes to customers who they can see are spending a lot of money with them. They do this to keep customers loyal to them. Once a customer is entered into the scheme they will receive special offers, such a s free bets and bonuses.