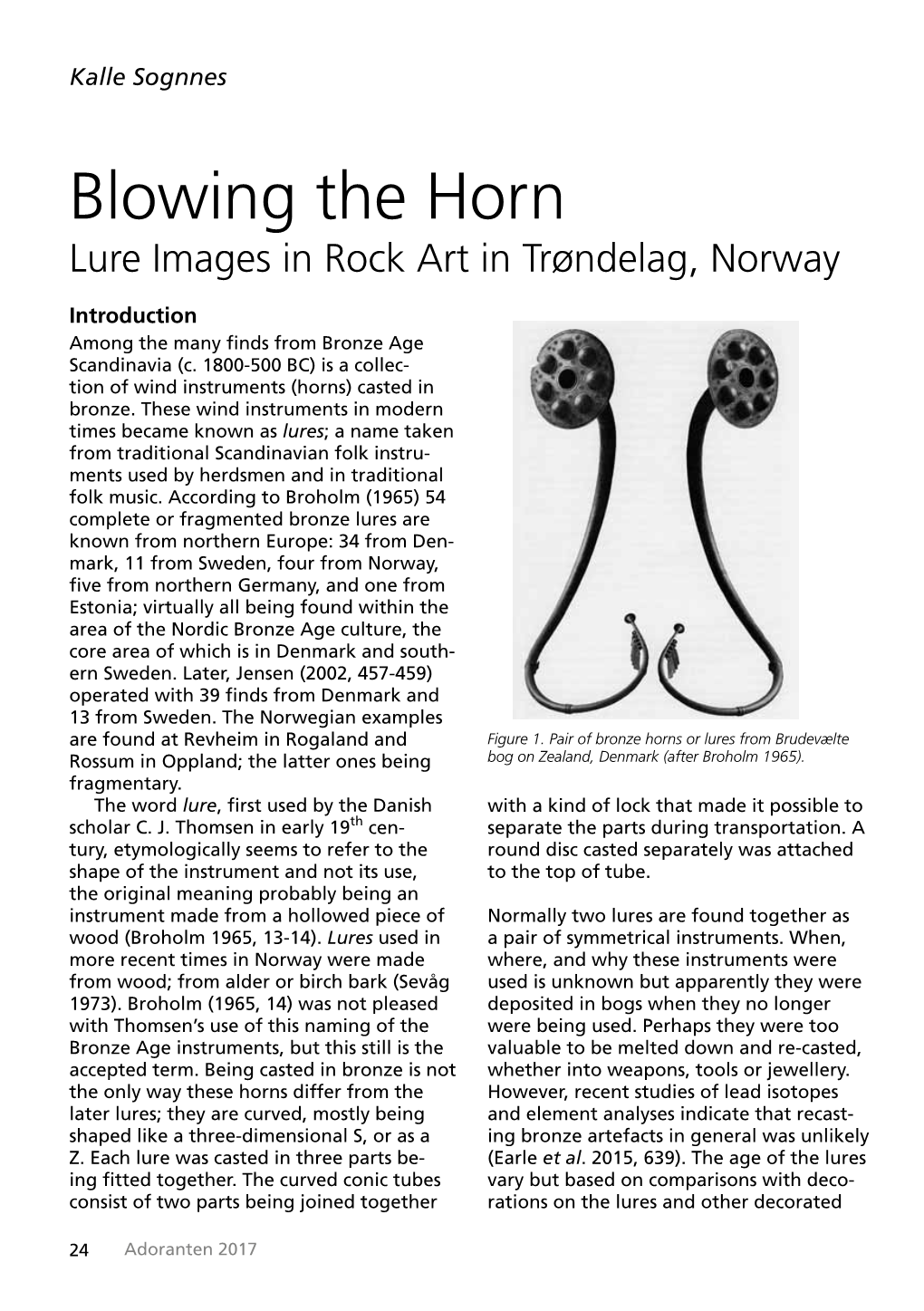

Blowing the Horn Lure Images in Rock Art in Trøndelag, Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vedtak Valgnemnda Fremmer Følgende Forslag for Årsmøtet 2021

ÅRSMØTE I TRØNDELAG BONDELAG 2021 SAK 13 Valgnemnda sin innstilling Valgnemnda i Trøndelag Bondelag har hatt 6 møter. 4 digitale møter og 2 fysisk. Digitalt valgnemndsarbeid er utfordrende, spesielt når medlemmer i valgnemnda ikke kjenner hverandre fra før. Intervjurunden med sittende styre ble delvis gjennomført fysisk og delvis digitalt. Valgnemndleder Odd Magne Storflor har ledet arbeidet i valgnemnda. Valgnemnda har i tillegg bestått av nestleder Norvald Berre, medlemmene Inger Hovde, Marit Kjøren, Kristine Ek Brattset og Tore Kaldahl. Valgnemnda har sendt ut informasjon til lokallagene og bedt om innspill. Av styrets medlemmer og varamedlemmer på valg, har alle gitt valgnemnda tilbakemelding om at de stiller seg til disposisjon for verv i Trøndelag Bondelag. Protokollen fra valgnemnda ble godkjent 19.01.2021. Innstillinga fra valgnemnda er enstemmig. Disse er ikke på valg, 4 styremedlemmer: Erlend Fiskum, Grong Annette Brede, Snåsa Kari Toftaker, Opdal Petter Harald Kimo, Rissa Vedtak Valgnemnda fremmer følgende forslag for årsmøtet 2021: A) Fylkesleder for 1 år Kari Åker Rissa Bondelag B) Styremedlem for 2 år Gunnar Alstad Skatval Bondelag Styremedlem for 2 år Eivind Såstad Mjøen Opdal Bondelag Styremedlem for 2 år Bjørnar Schei Fosnes Bondelag Styremedlem for 2 år Tove Schult Melhus Bondelag 1 C) 1. varamedlem for 1 år Inger Oldervik Frosta Bondelag 2. varamedlem for 1 år Yngve Røøyen Rindal Bondelag 3. varamedlem for 1 år Marit Kviseth Byneset Bondelag D) Nestleder for 1 år Erlend Fiskum Grong Bondelag F) Ordfører og varaordfører -

Ritual Landscapes and Borders Within Rock Art Research Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (Eds)

Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (eds) and Vangen Lindgaard Berge, Stebergløkken, Art Research within Rock and Borders Ritual Landscapes Ritual Landscapes and Ritual landscapes and borders are recurring themes running through Professor Kalle Sognnes' Borders within long research career. This anthology contains 13 articles written by colleagues from his broad network in appreciation of his many contributions to the field of rock art research. The contributions discuss many different kinds of borders: those between landscapes, cultures, Rock Art Research traditions, settlements, power relations, symbolism, research traditions, theory and methods. We are grateful to the Department of Historical studies, NTNU; the Faculty of Humanities; NTNU, Papers in Honour of The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and The Norwegian Archaeological Society (Norsk arkeologisk selskap) for funding this volume that will add new knowledge to the field and Professor Kalle Sognnes will be of importance to researchers and students of rock art in Scandinavia and abroad. edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Steberglokken cover.indd 1 03/09/2015 17:30:19 Ritual Landscapes and Borders within Rock Art Research Papers in Honour of Professor Kalle Sognnes edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 9781784911584 ISBN 978 1 78491 159 1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Cover image: Crossing borders. Leirfall in Stjørdal, central Norway. Photo: Helle Vangen Stuedal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. -

Implications for Ice Extent and Volume

RESEARCH ARTICLE GEOLOGICAL NOTE A buried late MIS 3 shoreline in northern Norway — implications for ice extent and volume Lars Olsen Geological Survey of Norway, 7491 Trondheim, Norway. [email protected] Buried beach gravel in northern Norway represents a late Middle Weichselian/Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 shoreline and indicates a significant late MIS 3 ice retreat. An age of c. 50–31 cal ka BP, or most likely c. 35–33 cal ka BP, obtained on shells, stratigraphical evidence and comparisons between local and global sea-level data, indicate a local/regional glacioisostatic depression which was about 50–70% of that of the Younger Dryas interval. This suggests a late MIS 3 ice thickness/ volume similar to or less than during the last part of the Preboreal, during which only minor or isolated remnants of the inland ice remained. Keywords: northern Norway, MIS 3, Scandinavian ice sheet, glacioisostacy Introduction maximum ice margin (Figure 1). Additional data, including sedimentary stratigraphy and dates from both coastal and inland The extension of the glaciers in the western part of the locations, indicate a much more extensive late MIS 3 ice retreat Scandinavian Ice Sheet during the Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) in most parts of Norway (e.g., Olsen et al. 2001a, b). However, 3 ice advance at c. 45 cal ka BP reached beyond the coastline the stratigraphic correlations between sites and between regions in SW Norway (e.g., Larsen et al. 1987). The subsequent ice are often hampered by dates of low precision and accuracy, which retreat, prior to the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), has been imply an uncertain location of the ice margin at each step in time discussed based on the distribution of sites which indicate ice- and therefore also an uncertain minimum ice extension. -

Tectonic Features of an Area N.E. of Hegra, Nord-Trøndelag, and Their Regional Significance — Preliminary Notes by David Roberts

Tectonic Features of an Area N.E. of Hegra, Nord-Trøndelag, and their regional Significance — Preliminary Notes By David Roberts Abstract Following brief notes on the low-grade metasediments occurring in an area near Hegra, 50 km east of Trondheim, the types of structures associated with three episodes of deformation of main Caledonian (Silurian) age are described. An outline of the suggested major stmctural picture is then presented. In this the principal structure is seen as a WNW-directed fold-nappe developed from the inverted western limb of the central Stjørdalen Anticline. A major eastlward closing recumbent syncline underlies this nappe-like structure. These initial structures were then deformed by at least twofur ther folding episodes. In conclusion, comparisons are noted between the ultimate fold pattern, the suggested evolution of these folds and H. Ramberg's experimentally produced orogenic structures. Introduction A survey of this particular area, situated north of the valley of Stjørdalen, east from Trondheim, was begun during the 1965 field-season and progressed during parts of the summers of 1966 and 1967 in conjunction with a mapping programme led by Statsgeolog Fr. Chr. Wolff further east in this same seg ment of the Central Norwegian Caledonides. Further geological mapping is contemplated, the aim being to eventually complete the 1 : 100,000 sheet 'Stjørdal' (rectangle 47 C). In view of the time factor involved in the comple tion of this work, and the renewed interest being devoted to the geological problems of the Trondheim region (Peacey 1964, Oftedahl 1964, Wolff 1964 and 1967, Torske 1965, Siedlecka 1967, Ramberg 1967), some notes on the tectonics of the Hegra area would seem appropriate at this stage. -

Poststeder Nord-Trøndelag Listet Alfabetisk Med Henvisning Til Kommune

POSTSTEDER NORD-TRØNDELAG LISTET ALFABETISK MED HENVISNING TIL KOMMUNE Aabogen i Foldereid ......................... Nærøy Einviken ..................................... Flatanger Aadalen i Forradalen ...................... Stjørdal Ekne .......................................... Levanger Aarfor ............................................ Nærøy Elda ........................................ Namdalseid Aasen ........................................ Levanger Elden ...................................... Namdalseid Aasenfjorden .............................. Levanger Elnan ......................................... Steinkjer Abelvær ......................................... Nærøy Elnes .............................................. Verdal Agle ................................................ Snåsa Elvalandet .................................... Namsos Alhusstrand .................................. Namsos Elvarli .......................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug i Schognen ................. Levanger Elverlien ....................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug ................................. Levanger Faksdal ......................................... Fosnes Appelvær........................................ Nærøy Feltpostkontor no. III ........................ Vikna Asp ............................................. Steinkjer Feltpostkontor no. III ................... Levanger Asphaugen .................................. Steinkjer Finnanger ..................................... Namsos Aunet i Leksvik .............................. -

Statistikk 2012

Årsstatistikk 2012 Utarbeid av Kjell Olav Storflor Korrigeringer rapporteres : [email protected] eller 952 52 277 Statistikk - 2012. Jenter 10 år 40 meter Idun Viem Ness Snåsa il 7,31 Snåsa 26.05 Jonna Dunfjeld Mølnvik Snåsa il 7,54 Snåsa 26.05 Lilly Marie Johansen Snåsa il 7,82 Snåsa 26.05 Sigrid Skaug Snåsa il 8,31 Snåsa 26.05 (manuell tidtaking) Sigrid Bonslet Røkke Flora il 8,2 Flora 16.05 Elisabet Husås Flora il 8,7 Flora 16.05 60 meter Malin Moen Lånke il 9,81 Stjørdal 10.06 Erle Musum Lyng Verdal fik 10,03 Steinkjer 16.06 Dagrun Ystad Derås Namdalseid il 10,24 Namdalseid 04.08 Jonna Dunfjeld Mølnvik Snåsa il 10,38 Steinkjer 12.08 Idun Viem Ness Snåsa il 10,39 Steinkjer 12.08 Sofie Aune Frol il 10,52 Levanger 27.08 Ine Tronstad Steinkjer fik 10,73 Steinkjer 15.05 Maria M. Johansen Frol il 10,74 Levanger 27.08 Guro Flatås Frol il 10,81 Levanger 04.06 Lilly Marie Johansen Snåsa il 10,86 Steinkjer 12.08 (manuell tidtaking) Ine Tronstad Steinkjer fik 10,0 Beitstad 04.09 Marte Aas Inderøy il 10,4 Inderøy 20.08 Innendørs Erle Musum Lyng Verdal fik 10,00 Steinkjer 08.12 Ine Tronstad Steinkjer fik 10,61 Steinkjer 19.01 200 meter Innendørs Erle Musum Lyng Verdal fik 34,28 Steinkjer 08.12 Ine Tronstad Steinkjer fik 37,14 Steinkjer 02.02 Hanna Marie Gangstad Steinkjer fik 39,29 Steinkjer 19.01 Maria Øgstad Verdal fik 41,27 Steinkjer 02.02 Ragne Kristin Brovold Steinkjer fik 41,42 Steinkjer 02.02 Lina Austli Berg Steinkjer fik 42,29 Steinkjer 19.01 600 meter Erle Musum Lyng Verdal fik 2.14,86 Steinkjer 16.06 Liv Merethe Prigge il Nybrott 2.22,1 -

Connected by Water, No Matter How Far. Viking Age Central Farms at the Trondheimsfjorden, Norway, As Gateways Between Waterscapes and Landscapes

Connected by water, no matter how far. Viking Age central farms at the Trondheimsfjorden, Norway, as gateways between waterscapes and landscapes Birgit Maixner Abstract – During the Viking Age, the Trondheimsfjorden in Central Norway emerges as a hub of maritime communication and exchange, supported by an advanced ship-building technology which offered excellent conditions for water-bound traffic on both local and supra-re- gional levels. Literary and archaeological sources indicate a high number of central farms situated around the fjord or at waterways leading to it, all of them closely connected by water. This paper explores the role of these central farms as gateways and nodes between waterscapes and landscapes within an amphibious network, exemplified by matters of trade and exchange. By analysing a number of case studies, their locations and resource bases, the partly different functions of these sites within the frames of local and supra-regional exchange networks become obvious. Moreover, new archaeological finds from private metal detecting from recent years indicate that bul- lion-based trivial transactions seem to have taken place at a large range of littoral farms around the Trondheimsfjorden, and not, as could be expected, only in the most important central farms or a small number of major trading places. Key words – archaeology; Viking Age; Norway; central farms; waterscapes; archaeological waterscapes; regional trade; exchange and communication; metal-detector finds; maritime cultural landscape; EAA annual meeting 2019 Titel – Durch Wasser verbunden. Wikingerzeitliche Großhöfe am Trondheimsfjord, Norwegen, als Tore und Verknüpfungspunkte zwischen Wasser- und Landwelten Zusammenfassung – Der Trondheimsfjord in Mittelnorwegen präsentiert sich während der Wikingerzeit als eine Drehscheibe für maritime Kommunikation und Warenaustausch, unterstützt durch eine hochentwickelte Schiffsbautechnologie, welche exzellente Voraussetzungen sowohl für den lokalen als auch den überregionalen Verkehr auf dem Wasser bot. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Namsos Inderøy Innherred Stjørdal Meråker Steinkjer

NAMSOS MERÅKER INDERØY STEINKJER INNHERRED GRONG STJØRDAL BEITSTAD 2020 Foto: Siv Fiskvik Foto: Siv Våre turregler: Foto: Mari Louise Fossland - Alle barn kan gå på tur. - Vi vil gjerne ha med en venn. - Vi vil være med å planlegge turen. - Vi har lyst til å gå foran og bestemme farten. - Vi vil ha tid til å leke og oppleve spennende ting underveis. - Vi vil ha tid til å snakke om det vi ser og opplever på turen. - Vi vil ha no` godt på toppen. Dato Aktivitet / turmål 2. februar - Vi vil kose oss om kvelden når Setertun vi er på overnattingstur. 24.mai Topptur - Vi vil ikke være frosne, våte Valan eller redde. 22.-23. Overnattingstur august Kalvøya 6. september Tømte naturlekeplass Namdalseid 18. oktober Reflekstur til uglas plass 29. november Juletur Følg med på nettsiden vår og Bråten Facebook-sidene til de ulike turlagene. Foto: Eirik Vyen Foto: Eirik BARNAS TURREGLER BARNAS Barnas Turlag Inderøy Foto: Anne Grethe Holmvik Foto: Anne Grethe Dato Aktivitet / turmål 2. februar Skallstuggu 2. eller 4. mars Skileik og kveldsmattur Torsbustaden 11. mars Aking og kveldsmattur Leirådalen 6. april Påskeeggjakt Røstadfjæra 6.-7.juni Overnattingstur Telt, lavvo, hengekøye, under åpen himmel. Tromsdalen 14. juni Sommeravslutning Sundsand Dato Aktivitet / turmål 2. februar 6. september Skihytta på Røra Skallstuggu 23. april Kveldsmattur til Røsethavna 14. oktober Refleksløype og kveldsmattur Torsbustaden 14. juni Aktivitetsdag på Sundsand November Aktivitetskveld Trønderhallen 6. september «Trillegruppa prøver å få til tur Liatjønna i Mosvik hver uke. Alle med små barn og fri på dagtid er velkommen med 6. desember Nissegrøtfest 30. -

7317 Buss Rutetabell & Linjerutekart

7317 buss rutetabell & linjekart 7317 Egge Ungdomskole Vis I Nettsidemodus 7317 buss Linjen Egge Ungdomskole har 2 ruter. For vanlige ukedager, er operasjonstidene deres 1 Egge Ungdomskole 07:35 2 Melland 14:15 Bruk Moovitappen for å ƒnne nærmeste 7317 buss stasjon i nærheten av deg og ƒnn ut når neste 7317 buss ankommer. Retning: Egge Ungdomskole 7317 buss Rutetabell 26 stopp Egge Ungdomskole Rutetidtabell VIS LINJERUTETABELL mandag 07:35 tirsdag 07:35 Vellamelen Namsosvegen 983, Norway onsdag 07:35 Beitstad torsdag 07:35 Brattbergsvegen 2, Norway fredag 07:35 Østvik lørdag Opererer Ikke Kvarving søndag Opererer Ikke Namsosvegen 701, Norway Korsenget Klætt 7317 buss Info Namsosvegen 546, Norway Retning: Egge Ungdomskole Stopp: 26 Jådåren Reisevarighet: 49 min Namsosvegen 475, Norway Linjeoppsummering: Vellamelen, Beitstad, Østvik, Kvarving, Korsenget, Klætt, Jådåren, Røsegg, Røsegg Gulling, Dyrstad, Asp, Rungstad, Sneve, Egge Ungdomsskole, Vammen, Nordsida, Nordsileiret, Gulling Steinkjer Montessoriskole, Nordsileiret, Bogen, Steinvika Terrasse, Steinvika, Søndre Egge, Dyrstad Lundsengvegen, Egge Barneskole, Egge Ungdomsskole Asp Kvamsvegen 781, Norway Rungstad Sneve Egge Ungdomsskole Vammen Nordsida Kongens gate, Steinkjer Nordsileiret Jæktskippergata 1, Steinkjer Steinkjer Montessoriskole Nordsileiret Jæktskippergata 1, Steinkjer Bogen Bogavegen 103, Steinkjer Steinvika Terrasse Bogavegen 126, Steinkjer Steinvika Bogavegen 145, Steinkjer Søndre Egge Balders Veg 3, Steinkjer Lundsengvegen Lundsengvegen 105, Steinkjer Egge Barneskole -

ANNUAL REPORT 2001 Omslag Spb1 for Pdf 06.05.02 09:20 Side 3

omslag SpB1 for pdf 06.05.02 09:20 Side 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2001 omslag SpB1 for pdf 06.05.02 09:20 Side 3 COVER PHOTO STEINAR HANSEN KARUSELL SBM-engelsk-2.ver ny 06.05.02 08:50 Side 1 Contents Art worth keeping alive 4 3 Main point 8 Main figures 9 2001: Many challenges, but solid operations and good results 11 Directors’ Report 12 Board of Directors 30 Profit and loss account 32 Balance sheet 33 Profit and loss account specifications 34 Balance sheet specifications 36 Accounting and Valuation Principles 38 Notes 40 Cash flow statement 61 Auditor’s report 62 Statement by the Control Committee 63 Main figures branch offices 64 Financial summary 65 Primary capital certificates (PCCs) 66 Organizational chart 67 Governing bodies 68 Marketing the bank 70 SBM-engelsk-2.ver ny 06.05.02 08:50 Side 2 Steinar Hansen Pictorial artist Art worth keeping alive 4 Were it not for patrons able to pay but most of all exciting.The night- The biggest commissioner of assign- for artists’ services, the history of art mare was the thought of 900 poor ments in the history of art was not would be a sad story.The interplay prints, but that was part and parcel a bank, but the church.Think of the between patron and artist is as long of the challenge. Not only had I Gothic cathedrals and the artistic as the history of art itself. Art would received SpareBank 1 Midt-Norge’s endeavour they represent. Johan have been produced regardless, for culture award for 2001, which this Sebastian Bach’s (1685-1750) the artist is a creative soul - but year bore the name Marvin Wiseths production was largely the fruit of the format, the dimensions and culture prize and was worth NOK church finance.The Reformation the development would have been 25,000; I also got the dream job. -

Kommunevalgene 1919

NORGES OFFISIELLE STATISTIKK. VI. 189. KOMMUNEVALGENE 1919. (Élections en 1919 pour les conseils communaux et municipaux.) UTGITT AV DET STATISTISKE CENTRALBYRA. KRISTIANIA. I KOMMISJON HOS H. ASCHEHOUG & CO. 1920. Kommunevalgene 1907 med oplysninger om valgene i 1901 og delvis i 1904 se Norges Offisielle Statistikk, rekke V, 61; Kommunevalgene 1910, 1918 og 1916, se rekke V, 137 og rekke VI, 12 og 110. Kristiania — Arbeidernes Aktietrykkeri. Innhold. — Table des matières. Side (pages). Innledning. — Introduction 1* Tabell 1. Kommunevalgene i landdistriktene. Sammendrag fylkesvis. — Élections aux conseils communaux dans les districts ruraux, par préfecture. ........................ 2 — 2. Antall stemmeberettigede, avgivne stemmer og valgte repre- sentanter i de enkelte herreder. ~ Nombre des électeurs inscrits, des voies et des membres élus dans les communes rurales . 8 — 3. Kommunevalgene i byene. •—Élections aux conseils municipaux des villes 28 — 4. Antall stemmeberettigede og avgivne stemmer m. v. i de"mnrdre byer. — Nombre des électeurs inscrits et des votants, etc. dans les villes non-spécifiées au tableau précédent 33 — 5. De offisielle valglisters stemmetall ved forholds valg i land- distriktene. Sammendrag fylkesvis. — Élection proportionnelle dans les districts ruraux: nombre de voix des bulletins val- ables répartis sur partis, par préfecture 34 — 6. Representantplassenes fordeling på de enkeite partigruppers lister ved forholdsvalg i landdistriktene. Sammendrag fylkes- vis. — Élection proportionnelle dans les districts ruraux: représentants élus répartis sur partis, par préfecture 36 — 7. De offisielle valglisters stemmetall ved forholdsvalg i byene. — Élection proportionnelle dans les villes: nombre de voix des bulletins valables répartis sur partis 38 8. Representantplassenes fordeling på de enkelte partigruppers lister ved forholdsvalg i byene. — Élection proportionnelle dans les villes: représentants élus répartis sur partis 40 Innledning.