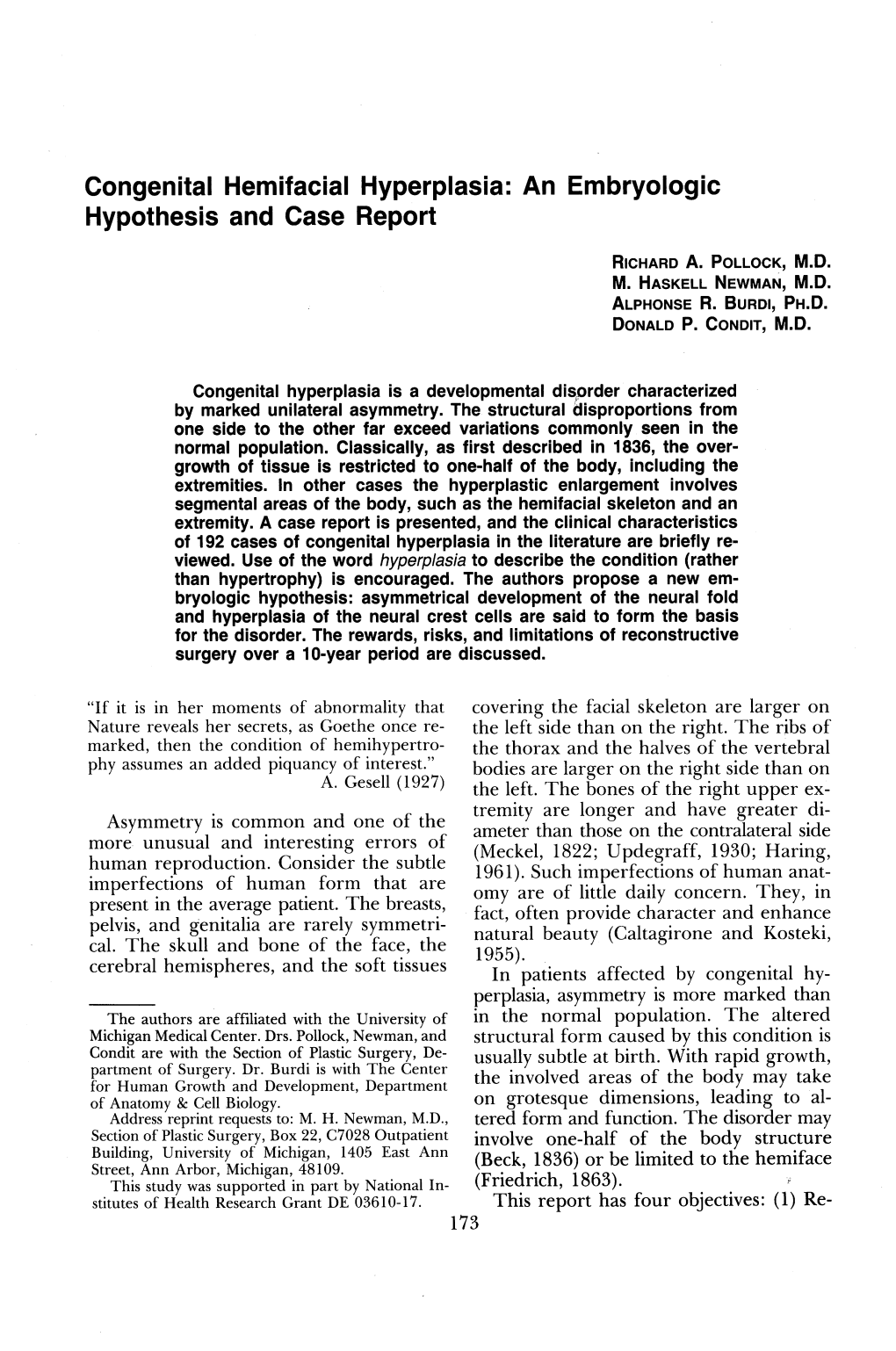

(Friedrich, 1863). This Report Has Four Objectives: (1) Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for Dental Fees for General Dentists January 2020

Guide for Dental Fees for General Dentists January 2020 Copyright © 2019 by the Alberta Dental Association and College ALBERTA DENTAL ASSOCIATION AND COLLEGE Preamble The fees listed herein are published to serve merely as a guide. No dentist receiving this list is under any obligation to accept the fees itemized. Any dentist who does not use all or any of these fees will in no way suffer in their relations with the Alberta Dental Association and College or any other body, group or committee affiliated with or under the control of the Alberta Dental Association and College. A genuine suggested fee guide is one which is issued merely for professional information purposes without raising any intention or expectation whatsoever that the membership will adopt the guide for their practices. Dentists have the right and freedom to use any dental codes that are included in the Alberta Uniform System of Coding and List of Services. Dentists may use these fees to assist them in determining their own professional fees. A suggested protocol to follow in order to eliminate the possibility of patient misunderstandings regarding the fees for dental treatment is: a. Perform a thorough oral examination for the patient. b. Explain, carefully, the particular problems encountered in this patient's mouth. Describe your treatment plan and prognosis, in a manner, which the patient can fully understand. Assure yourself that the patient has understood the presentation. c. Present your fee for treatment, before the commencement of treatment. d. Arrange financial commitments in such a manner that the patient understands their obligation. e. -

Core Curriculum for Surgical Technology Sixth Edition

Core Curriculum for Surgical Technology Sixth Edition Core Curriculum 6.indd 1 11/17/10 11:51 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Healthcare sciences A. Anatomy and physiology 7 B. Pharmacology and anesthesia 37 C. Medical terminology 49 D. Microbiology 63 E. Pathophysiology 71 II. Technological sciences A. Electricity 85 B. Information technology 86 C. Robotics 88 III. Patient care concepts A. Biopsychosocial needs of the patient 91 B. Death and dying 92 IV. Surgical technology A. Preoperative 1. Non-sterile a. Attire 97 b. Preoperative physical preparation of the patient 98 c. tneitaP noitacifitnedi 99 d. Transportation 100 e. Review of the chart 101 f. Surgical consent 102 g. refsnarT 104 h. Positioning 105 i. Urinary catheterization 106 j. Skin preparation 108 k. Equipment 110 l. Instrumentation 112 2. Sterile a. Asepsis and sterile technique 113 b. Hand hygiene and surgical scrub 115 c. Gowning and gloving 116 d. Surgical counts 117 e. Draping 118 B. Intraoperative: Sterile 1. Specimen care 119 2. Abdominal incisions 121 3. Hemostasis 122 4. Exposure 123 5. Catheters and drains 124 6. Wound closure 128 7. Surgical dressings 137 8. Wound healing 140 1 c. Light regulation d. Photoreceptors e. Macula lutea f. Fovea centralis g. Optic disc h. Brain pathways C. Ear 1. Anatomy a. External ear (1) Auricle (pinna) (2) Tragus b. Middle ear (1) Ossicles (a) Malleus (b) Incus (c) Stapes (2) Oval window (3) Round window (4) Mastoid sinus (5) Eustachian tube c. Internal ear (1) Labyrinth (2) Cochlea 2. Physiology of hearing a. Sound wave reception b. Bone conduction c. -

Functional Morphology of Tissues in Children with Bilateral Lip

Liene Smane-Filipova FUNCTIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF TISSUES IN ONTOGENETIC ASPECT IN CHILDREN WITH COMPLETE BILATERAL CLEFT LIP AND PALATE Summary of the Doctoral Thesis for obtaining the degree of a Doctor of Medicine Speciality – Morphology Scientific supervisors: Dr. med., Dr. habil. med. Professor Māra Pilmane Riga, 2016 1 The Doctoral Thesis was carried out at the Department of Morphology, Institute of Anatomy and Anthropology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Latvia Scientific supervisors: Dr. med., Dr. habil. Med., Professor Māra Pilmane, Rīga Stradiņš University, Latvia Official reviewers: Dr. med., Professor Ilze Štrumfa, Rīga Stradiņš University, Latvia Dr. med. vet., Professor Arnis Mugurēvičs, Latvia University of Agriculture Dr. med., Associate Professor Renata Šimkūnaitėi-Rizgeliene, Vilnius University, Lithuania Defence of the Doctoral Thesis will take place at the public session of the Doctoral Council of Medicine on 9 December 2016 at 15.00 in Hippocrates Lecture Theatre, 16 Dzirciema Street, Rīga Stradiņš University. Doctoral thesis is available in the RSU library and at RSU webpage: www.rsu.lv The Doctoral Thesis was carried out with “Support for Doctoral Students in Mastering the Study Programme and Acquisition of a Scientific Degree in Rīga Stradiņš University”, agreement No 2009/0147/1DP/1.1.2.1.2/09/IPIA/VIAA/009” Secretary of the Doctoral Council: Dr. med., Assistant Professor Andrejs Vanags 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 -

Treatments for Ankyloglossia and Ankyloglossia with Concomitant Lip-Tie Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 149

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 149 Treatments for Ankyloglossia and Ankyloglossia With Concomitant Lip-Tie Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 149 Treatments for Ankyloglossia and Ankyloglossia With Concomitant Lip-Tie Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2012-00009-I Prepared by: Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center Nashville, TN Investigators: David O. Francis, M.D., M.S. Sivakumar Chinnadurai, M.D., M.P.H. Anna Morad, M.D. Richard A. Epstein, Ph.D., M.P.H. Sahar Kohanim, M.D. Shanthi Krishnaswami, M.B.B.S., M.P.H. Nila A. Sathe, M.A., M.L.I.S. Melissa L. McPheeters, Ph.D., M.P.H. AHRQ Publication No. 15-EHC011-EF May 2015 This report is based on research conducted by the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. 290-2012-00009-I). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for the application of clinical judgment. -

CPC® Certification Review

CPC® Certification Review 1 CPT® CPT® copyright 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT®, and the AMA is not recommending their use. The AMA does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense medical services. The AMA assumes no liability for data contained or not contained herein. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. 2 ICD-9-CM Coding 3 NEC vs. NOS • NEC Not elsewhere classifiable “We know what’s wrong, but there isn’t a specific code for it.” • NOS Not otherwise specified “We aren’t sure what’s wrong.” 4 Punctuation [ ] Brackets: in tabular enclose synonyms or alternate wording Example: 008.0 Escherichia coli [E. coli] [ ] Slanted brackets: in index identifies manifestations and indicates sequence. Example: Diabetes, diabetic 250.0x cataract 250.5x [366.41] 5 Punctuation ( ) Parentheses: enclose supplementary words that may be present in the description Example: Cyst (mucus)(retention)(serous)(simple) 6 Additional Terms 599.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified Excludes candidiasis of urinary tract (112.2) urinary tract infection of newborn (771.82) 280 Iron deficiency anemias anemia Includes asiderotic hypochromic-microcytic sideropenic 7 Use Additional Code 282.42 Sickle-cell thalassemia with crisis Sickle-cell thalassemia with vaso-occlusive pain Thalassemia Hb-S disease with crisis Use additional code for the type of crisis, such as: acute chest sydrome (517.3) splenic sequestration (289.52) 8 Use Additional Code, if Applicable 416.2 Chronic pulmonary embolism Use additional code, if applicable, for associated long-term (current) use of anticoagulants (V58.61) 9 Combination Codes Single codes: 787.02 Nausea alone 787.03 Vomiting alone Combination code: 787.01 Nausea with vomiting 10 Steps to Look Up a Diagnosis Code 1. -

Pediatric Surgery Dentistry 9Th

Примірник для самопідготовки студентів Профіль: Хірургія Курс: 5 курс, 9 осінній семестр Мова: Англійська Тема: /5 курс/ Всього завдань: 340 visible. Neoplasm is painless, soft during palpation. What 15. In the 7-year-old patient the overgrowth of the gums 1. Parents of 2 years old girl complain of bright red color is preliminary diagnosis? around the tooth neck was revealed. The overgrowth is of formation of size 1 to 1.5 cm, that is not elevated over the A. Lipoma the bright red colour with irregular form, hilled of the soft mucous level on the upper lip area. The neoplasm B. Haemangioma consistency, easy bleeding (as after the injury, and changes its color during pressing, paleness appears. C. Lymphangioma independently). Which disease is responsible for this Regional lymph nodes, clinical blood and urine tests are D. Fibroma clinical picture? without pathological changes. Put the preliminary E. Papilloma A. Angiomatous epulis diagnosis? B. Lipoma A. Capillary hemangioma 8. Mum of the 4-year-old child complains of a red dot spot C. Fibrous epulis B. Capillary lymphangioma on his face. It appeared a month ago and is growing. D. Fibroma C. Cavernous lymphangioma During the examination the pathological red spot of E. Haemangioma D. Cavernous hemangioma spidery form in the infraorbital area was revealed. During E. Pyogenic granuloma putting pressure the painting disappears in the centre of 16. Parents of the 3-week-old baby-girl are complaining of the spot. What is the preliminary diagnosis? the presence of the red round in shape spot, 2 cm in 2. The 3 month boy's mother complains of the presence of A. -

Auditors' Desk Reference

Auditors’ Desk Reference 2013 Contents Chapter 1. Auditing Processes and Protocols ........................................... 1 Claims Reimbursement ......................................................................................................... 1 Role of Audits ........................................................................................................................... 4 Medical Record Documentation ......................................................................................... 7 Chapter 2. Focusing and Performing Audits .......................................... 17 Ten Steps To Audits ..............................................................................................................17 Identifying Potential Problem Areas ................................................................................19 Clean Claims ...........................................................................................................................19 Remittance Advice Review .................................................................................................28 Non-medical Code Sets .......................................................................................................29 Common Reasons for Denial for Medicare .....................................................................30 General Coding Principles that Influence Payment .....................................................46 Correspondence ....................................................................................................................62 -

Procedure Codes Section 5

NEW YORK STATE MEDICAID PROGRAM PHYSICIAN – PROCEDURE CODES SECTION 5 - SURGERY Physician – Procedure Codes, Section 5 - Surgery _____________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents ANESTHESIA SECTION------------------------------------------------------------------------2 GENERAL INFORMATION AND RULES------------------------------------------------2 CALCULATION OF TOTAL ANESTHESIA VALUES --------------------------------4 SURGERY SECTION ----------------------------------------------------------------------------5 GENERAL INFORMATION AND RULES------------------------------------------------5 SURGERY SERVICES ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 11 GENERAL -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 INTERGUMENTARY SYSTEM ----------------------------------------------------------- 11 MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM--------------------------------------------------------- 38 RESPIRATORY SYSTEM ---------------------------------------------------------------- 108 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM --------------------------------------------------------- 123 HEMIC AND LYMPHATIC SYSTEMS ------------------------------------------------ 167 MEDIASTINUM AND DIAPHRAGM --------------------------------------------------- 170 DIGESTIVE SYSTEM---------------------------------------------------------------------- 171 URINARY SYSTEM ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 214 MALE GENITAL SYSTEM --------------------------------------------------------------- -

Schedule of Benefits

SERVICES OF DENTISTS Schedule of Benefits Dental Services Under The Health Insurance Act (April 1, 2005) Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care April 1, 2005 SERVICES OF DENTISTS GENERAL PREAMBLE The following apply to Parts I, II and III 1. A service described in this Schedule includes all in-hospital visits, the in-hospital operative procedure, the usual postoperative care and one post discharge follow-up visit. 2. The services rendered by dentists that are prescribed as insured services are the services set out in Parts I, II and III of the Schedule of Dental Benefits. 3. "Specialist" means, (a) with respect to dental services rendered in Ontario, a dental surgeon who holds a specialty certificate of registration from the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. (b) with respect to dental services rendered elsewhere in Canada, a dental surgeon who holds a designation from a professional regulatory body in the Canadian province or territory outside of Ontario where the services are rendered that, in the opinion of the General Manager, is equivalent to the designation referred to in clause (a), or (c) with respect to dental services rendered outside Canada, a dental surgeon who holds a designation in the jurisdiction outside Canada where the services are rendered that, in the opinion of the General Manager, is equivalent to the designation referred to in clause (a). 4. Subsequent Operative Procedures: When complications occur following a procedure and a subsequent procedure becomes necessary for the same condition, or for a new condition, the full listed fee shall be payable for each procedure. -

Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment

Plastic Surgery International Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment Guest Editors: Nivaldo Alonso, David M. Fisher, Luiz Bermudez, and Renato da Silva Freitas Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment Plastic Surgery International Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment Guest Editors: Nivaldo Alonso, David M. Fisher, Luiz Bermudez, and Renato da Silva Freitas Copyright © 2013 Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “Plastic Surgery International.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Robert J. Allen, USA Ali Gurlek,¨ Turkey H. Mizuno, Japan Bishara S. Atiyeh, Lebanon Robert Hierner, Germany Selahattin Ozmen,¨ Turkey Francesco Carinci, Italy Georg M. Huemer, Austria LeeL.Q.Pu,USA Alain M. Danino, Canada Hirohiko Kakizaki, Japan G. L. Robb, USA Barry L. Eppley, USA Nolan S. Karp, USA Thomas Schoeller, Austria Joel S. Fish, Canada Yoshihiro Kimata, Japan Nicolo Scuderi, Italy N. H. Goldberg, USA Taro Kono, Japan Stephen M. Warren, USA Lawrence J. Gottlieb, USA M. Lehnhardt, Germany James E. Zins, USA Adriaan O. Grobbelaar, UK Albert Losken, USA Wolfgang Gubisch, Germany Malcolm W. Marks, USA Contents Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment, Nivaldo Alonso, David M. Fisher, Luiz Bermudez, and Renato da Silva Freitas Volume 2013, Article ID 372751, 1 page Implementing the Brazilian Database on Orofacial Clefts, Isabella Lopes Monlleo,´ -

ABSTRACTS BACHMAYER DI, Ross RB, Munro IR. Maxillary Growth

ABSTRACTS BACHMAYER DI, Ross RB, Munro IR. Maxillary growth following Lefort III advancement surgery in Crouzon, Apert, and Pfeiffer syndromes. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1987; 90:420-430. The authors studied facial growth following Le Fort III osteotomies in 19 children with Crouzon (7), Apert (10), and Pfeiffer (2) syndromes. The group containing 12 males and 7 females with a mean age of 7.1 years at surgery were followed an average of 5.3 years after the surgeries. The authors compared the operated syn- drome group with a group of 52 unoperated syndrome patients: Crouzon (26); Apert (23), and Pfeiffer (3). They also compared the operated group with normative data from the University of Michigan School Growth Study. The authors found that the horizontal growth of the maxilla of the operated syndrome group was negligible (less than 0.1 mm/year) and different from the unoperated syndrome group (0.7 mm/year) and the normal group (1.3 mm/year). The authors found that vertical growth of the maxilla was similar in all three groups. They concluded that the surgery was justifiable, even though a subsequent maxillary advancement is required after growth is completed. (Staley) Reprints: Dr. R. Bruce Ross Head, Division of Orthodontics The Hospital for Sick Children 555 University Avenue Toronto, Ontario MSG 1X8 FRIEDE H, FIGUEROA AA, NAEGELE ML, GoUuLp HJ, Kay CN, Apuss H. Craniofacial growth data for cleft lip patients infancy to 6 years of age: potential applications. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1986; 90:388-409. The authors provide longitudinal roentgencephalometric growth data on a group of 38 cleft lip only and 34 cleft lip and alveolus subjects from infancy to 6 years of age. -

Laser Soft Tissue Molding Technique 61 CASE REPORT Available At

CASE REPORT available at www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/islsm Soft tissue molding technique in cleft lip and palate patient using laser surgery in combination with orthodontic appliance: A case report Pornpat Theerasopon 1, Tasanee Wangsrimongkol 2 and Sajee Sattayut 3 1: Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand and Lasers in Dentistry Research Group, Khon Kaen University 2: Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Khon Kaen University 3: Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand and Lasers in Dentistry Research Group, Khon Kaen University Background: Although surgical treatment protocols for cleft lip and palate patients have been established, many patients still have some soft tissue defects after complete healing from surgical interventions. These are excess soft tissue, high attached fraena and firmed tethering scares. These soft tissue defects resulted shallowing of vestibule, restricted tooth movement, compromised peri- odontal health and trended to limit the maxillary growth. The aim of this case report was to pre- sent a method of correcting soft tissue defects after conventional surgery in cleft lip and palate patient by using combined laser surgery and orthodontic appliance. Case report: A bilateral cleft lip and palate patient with a clinical problem of shallow upper ante- rior vestibule after alveolar bone graft received a vestibular extension by using CO2 laser with abla- tion and vaporization techniques at 4 W and continuous wave. A customized orthodontic appli- ance, called a buccal shield, was placed immediately after surgery and retained for 1 month to 3 months until complete soft tissue healing.