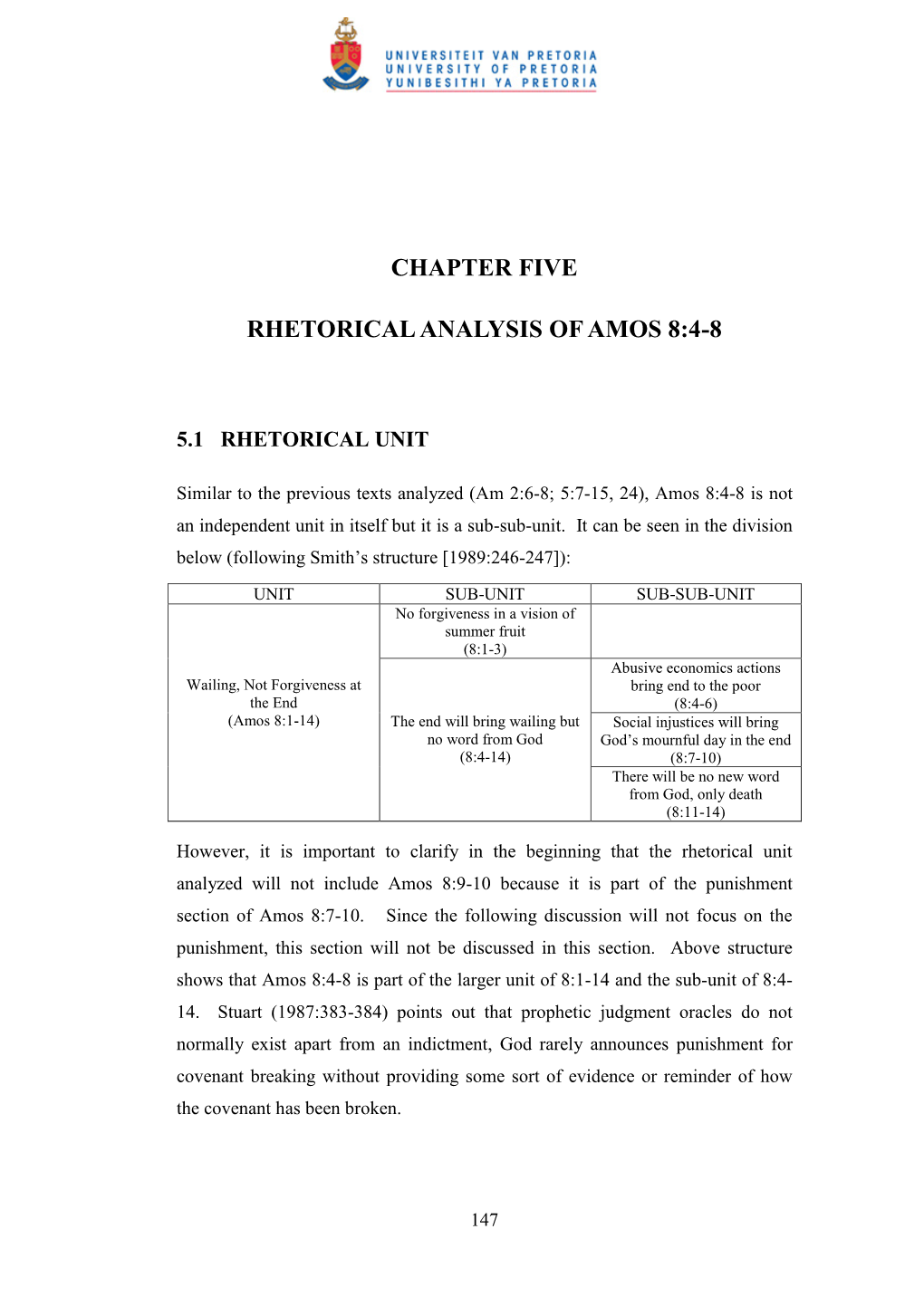

Chapter Five Rhetorical Analysis of Amos 8:4-8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Bible Lessons Commentary Amos 6:1-14 English Standard Version

International Bible Lessons Commentary Amos 6:1-14 English Standard Version International Bible Lessons Sunday, June 21, 2015 L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Lessons Series) for Sunday, June 21, 2015, is from Amos 6:1-14. Please Note: Some churches will only study Amos 6:4-8, 11-14. Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the verse-by-verse International Bible Lesson Commentary. Study Hints for Discussion and Thinking Further discusses Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further to help with class preparation and in conducting class discussion: these hints are available on the International Bible Lessons Commentary website along with the International Bible Lesson that you may want to read to your class as part of your Bible study. A podcast for this commentary is also available at the International Bible Lesson Forum. International Bible Lesson Commentary Amos 6:1-14 (Amos 6:1) “Woe to those who are at ease in Zion, and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria, the notable men of the first of the nations, to whom the house of Israel comes! Amos preached during the reign of King Jeroboam II [786 BC-746 BC], perhaps for only one year, which was all that would be necessary, perhaps because Amaziah told Amos to stop preaching (see Amos 5:10 and Amos 7:10-17). God condemned both Zion (Jerusalem) and Samaria (capital of the Kingdom of Israel) for their pride. At the time of Amos’ preaching, both kingdoms were powerful and prosperous compared to their neighboring nations. -

The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age

HAYYIM ANGEL The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age Introduction OF THE FIFTEEN “Latter Prophets”, Joel’s chronological setting is the most difficult to identify. Yet, the dating of the book potentially has significant implications for determining the overall purposes of Joel’s prophecies. The book’s outline is simple enough. Chapters one and two are a description of and response to a devastating locust plague that occurred in Joel’s time. Chapters three and four are a prophecy of consolation predict- ing widespread prophecy, a major battle, and then ultimate peace and pros- perity.1 In this essay, we will consider the dating of the book of Joel, the book’s overall themes, and how Joel’s unique message fits into his likely chronological setting.2 Dating Midrashim and later commentators often attempt to identify obscure figures by associating them with known figures or events. One Midrash quoted by Rashi identifies the prophet Joel with the son of Samuel (c. 1000 B.C.E.): When Samuel grew old, he appointed his sons judges over Israel. The name of his first-born son was Joel, and his second son’s name was Abijah; they sat as judges in Beer-sheba. But his sons did not follow in his ways; they were bent on gain, they accepted bribes, and they subvert- ed justice. (I Sam. 8:1-3)3 RABBI HAYYIM ANGEL is the Rabbi of Congregation Shearith Israel. He is the author of several books including Creating Space Between Peshat & Derash: A Collection of Studies on Tanakh. 21 22 Milin Havivin Since Samuel’s son was wicked, the Midrash explains that he must have repented in order to attain prophecy. -

Week 9 – Amos Connect: Choose 1 Connect Question and Discuss for 5

Week 9 – Amos Connect: choose 1 Connect question and discuss for 5-7 minutes. Describe where you have seen justice and righteousness prevail—where what is wrong is made right. Name one person you would like to have dinner with, past or present, real or fiction, and why. Read these passages aloud: Amos 2:6-3:15- God’s Judgment on Israel Amos 5:21-24 - The Day of the LORD, a dark day Amos 6:11-14 – God’s punishment of Israel Amos 7:14-17- Amos’ call. Amos 9:11-12 – Restoration of David’s kingdom Engage the text as a group: 1. What do you observe? God has strong words for Israel’s religious practices: “I hate, I despise your festivals…” 2. What questions do you have of these texts? E.g.) Why would Israel equate economic prosperity with God’s favor? Why weren’t keeping the religious practices themselves enough? Why does Amos matter? Amos matters because it shows us how deeply God cares for the lowly, the downtrodden, the oppressed, the marginalized. The book of Amos shows us that Israel taking material prosperity or economic security to equal God’s favor and approval was wrong. In Amos, God condemns the practices of Israel that built up wealth for itself and the 1% that hoarded it at the expense of the poor, while God shows compassion for the poor who are being oppressed because of the practices of the wealthy. If you live in the United States, you live in right now the most militarily powerful country in the world and the richest nation on earth. -

Amos 8: 1-12 Disturbing the Peace

Sunday, July 21, 2019 Proper 11 (Yr C) - Amos 8: 1-12 Disturbing the Peace Consolations and Desolations - At the close of every weekly meeting of the Men’s Group, we go around the table and mention our Highs and Lows, our Consolations and Desolations (as Ignatius of Loyola called them); those places where we found God and those in which God seems to be absent. - If the Men’s Group had a spiritual director, he or she might help us keep in mind that sometimes what we see as consolations are, in fact desolations • And that is what we find in the Book of Amos: - The wealthy people of Bethel of the Kingdom of Israel were certain that they were living in in a time of Consolation (that God was blessing their lives), when, in reality, as Amos tells them, what they are living in is a time of utter and complete desolation. - And yet, in this desolation, there is some hope, and we’ll see that later on. - But first, let’s look at Amos, the prophet himself and his times, and that ought to give us a more clearer understanding of how the people of Bethel mixed up their consolations and desolations. !1 of !9 Sunday, July 21, 2019 Amos of Tekoa - Amos was a shepherd and fig grower from Tekoa, a small town 5 miles south of Jerusalem, that sat upon a hill that rose above two valleys that descend to the Dead Sea. • Tekoa was a part of the southern Kingdom of Judah, but the marketplace for the wool from sheep of Amos was in Bethel a 2 ½ days journey away in the northern Kingdom of Israel. -

Pdf Israelian Hebrew in the Book of Amos

ISRAELIAN HEBREW IN THE BOOK OF AMOS Gary A. Rendsburg 1.0. The Location of Tekoa The vast majority of scholars continue to identify the home vil- lage of the prophet Amos with Tekoa1 on the edge of the Judean wilderness—even though there is little or no evidence to support this assertion. A minority of scholars, the present writer included, identifies the home village of Amos with Tekoa in the Galilee— an assertion for which, as we shall see, there is considerable solid evidence. 1.1. Southern Tekoa The former village is known from several references in Chroni- cles, especially 2 Chron. 11.6, where it is mentioned, alongside Bethlehem, in a list of cities fortified by Rehoboam in Judah. See also 2 Chron. 20.20, with reference to the journey by Jehosha- to the wilderness of Tekoa’.2‘ לְמִדְב ַּ֣ר תְקֹ֑וע phat and his entourage The genealogical records in 1 Chron. 2.24 and 4.5, referencing a 1 More properly Teqoaʿ (or even Təqōaʿ), but I will continue to use the time-honoured English spelling of Tekoa. 2 See also the reference to the ‘wilderness of Tekoa’ in 1 Macc. 9.33. © 2021 Gary A. Rendsburg, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.23 718 New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew Judahite named Tekoa, may also encode the name of this village. The name of the site lives on in the name of the Arab village of Tuquʿ and the adjoining ruin of Khirbet Tequʿa, about 8 km south of Bethlehem.3 1.2. -

![Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9626/qumran-hebrew-with-a-trial-cut-1qs-1289626.webp)

Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*

QUMRAN HEBREW (WITH A TRIAL CUT [1QS])* Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University One would think that after sixty years of studying the scrolls, scholars would have reached a consensus concerning the nature of the language of these texts. But such is not the case—the picture is no different for Qumran Hebrew (QH) than it is for identifying the sect of the Qum- ran community, for understanding the origins of the scroll depository in the caves, or for the classification of the archaeological remains at Qumran. At first glance, this is a bit difficult to comprehend, since in theory, at least, linguistic research should be the most objective form of scholarly inquiry, and the facts should speak for themselves—in contrast to, let’s say, the interpretation of texts, where subjectivity may be considered necessary at all times. But as we shall see, even though the data themselves are derived from purely empirical observation, the interpretation of the linguistic picture that emerges from the study of Qumran Hebrew has no less a range of options than the other subjects canvassed during this symposium. Before entering into such discussion, however, let us begin with the presentation of some basic facts. Of the 930 assorted documents from Qumran, 790, or about 85% of them are written in Hebrew (120 or about 13% are written in Aramaic, and 20 or about 2% are written in Greek). Of these 930, about 230 are biblical manuscripts, which * It was my pleasure to present this paper on three occasions during calendar year 2008: first and most importantly at the symposium entitled “The Dead Sea Scrolls at 60: The Scholarly Contributions of NYU Faculty and Alumni” (March 6), next at the “Semitic Philology Workshop” of Harvard University (November 20), and finally at the panel on “New Directions in Dead Sea Scrolls Scholarship” at the annual meeting of the Association of Jewish Studies held in Washington, D.C. -

A Canonical-Critical Study of Selected Traditions in the Book of Joel

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations 2-4-1992 A Canonical-Critical Study of Selected Traditions in the Book of Joel David D. Pettus Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pettus, David D., "A Canonical-Critical Study of Selected Traditions in the Book of Joel" (1992). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 2. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Canonical-Critical Study of Selected Traditions in the Book of Joel A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University in partial Fulfillment of the Reguirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By David D. Pettus Waco, Texas May, 1992 Approved by the Depar~m~t of Religi~~~ (signed) .Uh&c"j & l~) Approved by the Dissertation Committee: (signed) o Approved by Date: ABSTRACT The book of Joel presents a myriad of problems to the honest interpreter. For example, the inability to date firmly the book makes it exceedingly difficult to find an original meaning for the work. In addition, the failure of scholars to come to a consensus on the connection between the locust plague and the Day of Yahweh theme in the book exacerbates the interpretive problems further. -

Bulletin of the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies

Bulletin of the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies Volume 38 • 2005 Articles The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Septuagint....................... 1 John William Wevers The Septuagint in the Peshitta and Syro-Hexapla Translations of Amos 1:3–2:16 ..................................... 25 Petra Verwijs Tying It All Together: The Use of Particles in Old Greek Job......... 41 Claude Cox Rhetoric and Poetry in Greek Ecclesiastes....................... 55 James K. Aitken Calque-culations—Loan Words and the Lexicon.................. 79 Cameron Boyd-Taylor Gleanings of a Septuagint Lexicographer....................... 101 Takamitsu Muraoka Dissertation Abstract The Septuagint’s Translation of the Hebrew Verbal System in Chronicles.........................................109 Roger Blythe Good IOSCS Matters Program in Leiden....................................... 111 Executive Committee Meeting............................... 115 Business Meeting........................................ 118 Executive Report on Critical Texts............................ 119 Treasurer’s Report ....................................... 123 In memoriam Pierre Sandevoir............................... 127 i ii BIOSCS 38 (2005) Book Reviews Review of Adam Kamesar, Jerome, Greek Scholarship and the Hebrew Bible ...................................... 129 Alison Salvesen Review of Kristin De Troyer, Rewriting the Sacred Text: What the Old Greek Texts Tell Us about the Literary Growth of the Bible ..... 132 Robert J. V. Hiebert Review of Maarten J. J. Menken, -

Minor Prophets Fall, 2014

HB 750: Minor Prophets Fall, 2014 Instructor: Paul Kim Werner Hall 218 (By appointment preferred) (740) 363-1146 email: [email protected] website: http://www.mtso.edu/pkim COURSE DESCRIPTION In this course we will study the twelve minor prophets (Hosea ~ Malachi) in light of historical, canonical, and theological perspectives. Primary attention will be given to the interpretation of selected texts with regard to their socio-historical environments, to the intertextual correlation within the book and the canon, and to their theological implications for the life of the church and contemporary issues in a global context. OBJECTIVES With regard to several focal goals, through this course, we intend to: Read closely the entire twelve prophets in English at least once in this course; Engage in the exegetical practices of select texts from the twelve prophets; Become familiar with the contents, backgrounds, and scholarly issues; Become enamored with the “major” messages of these “minor” prophets; Make a conscientious effort of applying biblical texts toward preaching & ministry. TEXTBOOKS Required: Terence E. Fretheim, Reading Hosea – Micah: A Literary and Theological Commentary (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2013) James D. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve: Hosea – Jonah (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2011) James D. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve: Micah – Malachi (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2011) Recommended: John Goldingay and Pamela Scalise, Minor Prophets II (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2009) Daniel Berrigan, Minor Prophets: Major Themes (Eugene, Ore.: Wipf & Stock, 2009) Ronald L. Troxel, Prophetic Literature: From Oracles to Books (Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell, 2012) 2 REQUIREMENTS 1. Faithful Attendance and Participation in All Sessions: assigned readings should be done prior to each class session and students should be prepared to discuss the issues raised in the readings. -

Complacency Amos 6:1-7 Arrogance Says

Attitudes that Destroy: Complacency Amos 6:1-7 Arrogance says, “I’m kind of a big deal” and you need to treat me as such. It leads to misconceptions about the nature of self, life, and others; believing that they must control the world around them. Amos reveals in chapter six that arrogance leads to complacency and pride. The first seven verses deal with the by-product of complacency. Amos was a shepherd from Tekoa before God called him to be a prophet. And even though Tekoa is in the southern kingdom of Judah, Amos delivered his message to the northern kingdom of Israel. His ministry happened in the reign of Jeroboam II; which means that Amos prophesied some 40 to 60 years before the northern kingdom was destroyed by the Assyrians in 722 BC. I. Arrogance leads to complacency, which leads to a false sense of security; 6:1-3. 1 Woe to you who are complacent in Zion, and to you who feel secure on Mount Samaria, you notable men of the foremost nation, to whom the people of Israel come! 2 Go to Calneh and look at it; go from there to great Hamath, and then go down to Gath in Philistia. Are they better off than your two kingdoms? Is their land larger than yours? 3 You put off the evil day and bring near a reign of terror. Amos grieves that the people in Zion (the capital of Judah), as well as the people in Samaria (the capital of Israel), have an arrogant and deceptive feeling of well-being and security; however, their arrogance ignores the true state of affairs. -

The Book of Amos 8:1-12 a Reading from the Book Of

THE FIRST READING: The Book of Amos 8:1-12 A reading from the book of Amos…. This is what the Lord GOD showed me-- a basket of summer fruit. He said, "Amos, what do you see?" And I said, "A basket of summer fruit." Then the LORD said to me, "The end has come upon my people Israel; I will never again pass them by. The songs of the temple shall become wailings in that day," says the Lord GOD; "the dead bodies shall be many, cast out in every place. Be silent!" Hear this, you that trample on the needy, and bring to ruin the poor of the land, saying, "When will the new moon be over so that we may sell grain; and the sabbath, so that we may offer wheat for sale? We will make the ephah small and the shekel great, and practice deceit with false balances, buying the poor for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals, and selling the sweepings of the wheat." The LORD has sworn by the pride of Jacob: Surely I will never forget any of their deeds. Shall not the land tremble on this account, and everyone mourn who lives in it, and all of it rise like the Nile, and be tossed about and sink again, like the Nile of Egypt? On that day, says the Lord GOD, I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the earth in broad daylight. I will turn your feasts into mourning, and all your songs into lamentation; I will bring sackcloth on all loins, and baldness on every head; I will make it like the mourning for an only son, and the end of it like a bitter day. -

The Remnant Concept As Defined by Amos

[This paper has been reformulated from old, unformatted electronic files and may not be identical to the edited version that appeared in print. The original pagination has been maintained, despite the resulting odd page breaks, for ease of scholarly citation. However, scholars quoting this article should use the print version or give the URL.] Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 7/2 (Autumn 1996): 67-81. Article copyright © 1996 by Ganoune Diop. The Remnant Concept as Defined by Amos Ganoune Diop Institut Adventiste du Saleve France Introduction The study of the remnant concept from a linguistic perspective has revealed that this theme in Hebrew is basically represented by several derivatives of six different roots.1 Five of them are used in the eighth century B.C. prophetic writ- ings. The purpose of this article is to investigate the earliest prophetic writing, the book of Amos, in order to understand not only what is meant when the term “remnant” is used but also the reason for its use. We will try to answer the fol- lowing questions: What was the prophet Amos saying when he used this desig- nation (whether by itself or in association with patriarchal figures)? What are the characteristics of such an entity? What is the theological intention of the prophet? We have chosen this era because the eighth century prophets (Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Micah) were messengers to God’s people at a crucial time in their his- tory. All of them were sent to announce a message of judgment. Without a doubt the eighth century was “the time of the end” for the northern nation of Israel.