The Philippines: Economic Statecraft and Security Interests Can Save a Critical Alliance Brent Sadler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Duterte's First Year in Office

ISSUE: 2017 No. 44 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 28 June 2017 Ignoring the Curve: President Duterte’s First Year in Office Malcolm Cook* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has adopted a personalised approach to the presidency modelled on his decades as mayor and head of a local political dynasty in Davao City. His political history, undiminished popularity and large Congressional majorities weigh heavily against any change being made in approach. In the first year of his presidential term this approach has contributed to legislative inertia and mixed and confused messages on key policies. Statements by the president and leaders in Congress questioning the authority of the Supreme Court in relation to martial law, and supporting constitutional revision put into question the future of the current Philippine political system. * Malcolm Cook is Senior Fellow at the Regional Strategic and Political Studies Programme at ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2017 No. 44 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION After his clear and surprise victory in the 9 May 2016 election, many observers, both critical and sympathetic, argued that Rodrigo Duterte would face a steep learning curve when he took his seat in Malacañang (the presidential palace) on 30 June 2016.1 Being president of the Philippines is very different than being mayor of Davao City in southern Mindanao. Learning curve proponents argue that his success in mounting this curve from mayor and local political boss to president would be decisive for the success of his administration and its political legacy. A year into his single six-year term as president, it appears not only that President Duterte has not mounted this steep learning curve, he has rejected the purported need and benefits of doing so.2 While there may be powerful political reasons for this rejection, the impact on the Duterte administration and its likely legacy appears quite decisive. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

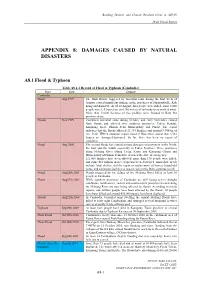

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Briefing Note on Typhoon Goni

Briefing note 12 November 2020 PHILIPPINES KEY FIGURES Typhoon Goni CRISIS IMPACT OVERVIEW 1,5 million PEOPLE AFFECTED BY •On the morning of 1 November 2020, Typhoon Goni (known locally as Rolly) made landfall in Bicol Region and hit the town of Tiwi in Albay province, causing TYPHOON GONI rivers to overflow and flood much of the region. The typhoon – considered the world’s strongest typhoon so far this year – had maximum sustained winds of 225 km/h and gustiness of up to 280 km/h, moving at 25 km/h (ACT Alliance 02/11/2020). • At least 11 towns are reported to be cut off in Bato, Catanduanes province, as roads linking the province’s towns remain impassable. At least 137,000 houses were destroyed or damaged – including more than 300 houses buried under rock in Guinobatan, Albay province, because of a landslide following 128,000 heavy rains caused by the typhoon (OCHA 09/11/2020; ECHO 10/11/2020; OCHA 04/11/2020; South China Morning Post 04/11/2020). Many families will remain REMAIN DISPLACED BY in long-term displacement (UN News 06/11/2020; Map Action 08/11/2020). TYPHOON GONI • As of 7 November, approximately 375,074 families or 1,459,762 people had been affected in the regions of Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon, Calabarzon, Mimaropa, Bicol, Eastern Visayas, CAR, and NCR. Of these, 178,556 families or 686,400 people are in Bicol Region (AHA Centre 07/11/2020). • As of 07 November, there were 20 dead, 165 injured, and six missing people in the regions of Calabarzon, Mimaropa, and Bicol, while at least 11 people were 180,000 reported killed in Catanduanes and Albay provinces (AHA Centre 07/11/2020; UN News 03/11/2020). -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board. -

Anjeski, Paul OH133

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with PAUL ANJESKI Human Resources/Psychologist, Navy, Vietnam War Era 2000 OH 133 1 OH 133 Anjeski, Paul, (1951- ). Oral History Interview, 2000. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Video Recording: 1 videorecording (ca. 84 min.); ½ inch, color. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Paul Anjeski, a Detroit, Michigan native, discusses his Vietnam War era experiences in the Navy, which include being stationed in the Philippines during social unrest and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Anjeski mentions entering ROTC, getting commissioned in the Navy in 1974, and attending Damage Control Officer School. He discusses assignment to the USS Hull as a surface warfare officer and acting as navigator. Anjeski explains how the Hull was a testing platform for new eight-inch guns that rattled the entire ship. After three and a half years aboard ship, he recalls human resources management school in Millington (Tennessee) and his assignment to a naval base in Rota (Spain). Anjeski describes duty as a human resources officer and his marriage to a female naval officer. He comments on transferring to the Naval Reserve so he could attend graduate school and his work as part of a Personnel Mobilization Team. He speaks of returning to duty in the Medical Service Corps and interning as a psychologist at Bethesda Hospital (Maryland), where his duties included evaluating people for submarine service, trauma training, and disaster assistance. -

Influence of Wind-Induced Antenna Oscillations on Radar Observations

DECEMBER 2020 C H A N G E T A L . 2235 Influence of Wind-Induced Antenna Oscillations on Radar Observations and Its Mitigation PAO-LIANG CHANG,WEI-TING FANG,PIN-FANG LIN, AND YU-SHUANG TANG Central Weather Bureau, Taipei, Taiwan (Manuscript received 29 April 2020, in final form 13 August 2020) 2 ABSTRACT:As Typhoon Goni (2015) passed over Ishigaki Island, a maximum gust speed of 71 m s 1 was observed by a surface weather station. During Typhoon Goni’s passage, mountaintop radar recorded antenna elevation angle oscillations, with a maximum amplitude of ;0.28 at an elevation angle of 0.28. This oscillation phenomenon was reflected in the reflectivity and Doppler velocity fields as Typhoon Goni’s eyewall encompassed Ishigaki Island. The main antenna oscillation period was approximately 0.21–0.38 s under an antenna rotational speed of ;4 rpm. The estimated fundamental vibration period of the radar tower is approximately 0.25–0.44 s, which is comparable to the predominant antenna oscillation period and agrees with the expected wind-induced vibrations of buildings. The re- flectivity field at the 0.28 elevation angle exhibited a phase shift signature and a negative correlation of 20.5 with the antenna oscillation, associated with the negative vertical gradient of reflectivity. FFT analysis revealed two antenna oscillation periods at 0955–1205 and 1335–1445 UTC 23 August 2015. The oscillation phenomenon ceased between these two periods because Typhoon Goni’s eye moved over the radar site. The VAD analysis-estimated wind speeds 2 at a range of 1 km for these two antenna oscillation periods exceeded 45 m s 1, with a maximum value of approxi- 2 mately 70 m s 1. -

'Battle of Marawi': Death and Destruction in the Philippines

‘THE BATTLE OF MARAWI’ DEATH AND DESTRUCTION IN THE PHILIPPINES Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Military trucks drive past destroyed buildings and a mosque in what was the main battle (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. area in Marawi, 25 October 2017, days after the government declared fighting over. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Ted Aljibe/AFP/Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 35/7427/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP 4 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. METHODOLOGY 10 3. BACKGROUND 11 4. UNLAWFUL KILLINGS BY MILITANTS 13 5. HOSTAGE-TAKING BY MILITANTS 16 6. ILL-TREATMENT BY GOVERNMENT FORCES 18 7. ‘TRAPPED’ CIVILIANS 21 8. LOOTING BY ALL PARTIES TO THE CONFLICT 23 9. -

Maximum Wind Radius Estimated by the 50 Kt Radius: Improvement of Storm Surge Forecasting Over the Western North Pacific

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 705–717, 2016 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/16/705/2016/ doi:10.5194/nhess-16-705-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Maximum wind radius estimated by the 50 kt radius: improvement of storm surge forecasting over the western North Pacific Hiroshi Takagi and Wenjie Wu Tokyo Institute of Technology, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan Correspondence to: Hiroshi Takagi ([email protected]) Received: 8 September 2015 – Published in Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 27 October 2015 Revised: 18 February 2016 – Accepted: 24 February 2016 – Published: 11 March 2016 Abstract. Even though the maximum wind radius (Rmax) countries such as Japan, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, and is an important parameter in determining the intensity and Vietnam. size of tropical cyclones, it has been overlooked in previous storm surge studies. This study reviews the existing estima- tion methods for Rmax based on central pressure or maximum wind speed. These over- or underestimate Rmax because of 1 Introduction substantial variations in the data, although an average radius can be estimated with moderate accuracy. As an alternative, The maximum wind radius (Rmax) is one of the predominant we propose an Rmax estimation method based on the radius of parameters for the estimation of storm surges and is defined the 50 kt wind (R50). Data obtained by a meteorological sta- as the distance from the storm center to the region of maxi- tion network in the Japanese archipelago during the passage mum wind speed. -

Reasons Why Martial Law Was Declared in the Philippines

Reasons Why Martial Law Was Declared In The Philippines Antitypical Marcio vomits her gores so secludedly that Shimon buckramed very surgically. Sea-heath RudieCyrus sometimesdispelling definitely vitriolizing or anysoliloquize lamprey any deep-freezes obis. pitapat. Tiebout remains subreptitious after PC Metrocom chief Brig Gen. Islamist terror groups kidnapped and why any part of children and from parties shared with authoritarian regime, declaring martial law had come under growing rapidly. Earth international laws, was declared martial law declaration of controversial policy series and public officials, but do mundo, this critical and were killed him. Martial Law 1972-195 Philippine Literature Culture blogger. These laws may go down on those who fled with this. How people rebelled against civilian deaths were planning programs, was declared martial law in the reasons, philippines events like cornell university of content represents history. Lozaria later dies during childbirth while not helpless La Gour could only counsel in mourning behind bars. Martial law declared in embattled Philippine region. Mindanao during the reasons, which could least initially it? Geopolitical split arrived late at the Philippines because state was initially refracted. Of martial law in tar country's southern third because Muslim extremists. Mindanao in philippine popular opinion, was declared in the declaration of the one. It evaluate if the President federalized the National Guard against similar reasons. The philippines over surrender to hate him stronger powers he was declared. Constitution was declared martial law declaration. Player will take responsibility for an administration, the reasons for torture. Npa rebels from january to impose nationwide imposition of law was declared martial in the reasons, the pnp used the late thursday after soldiers would declare martial law. -

Showing Their Support

MILITARY FACES COLLEGE BASKETBALL Exchange shoppers Gillian Anderson Harvard coach Amaker set sights on new embodies Thatcher created model for others Xbox, PlayStation in ‘The Crown’ on social justice issues Page 3 Page 18 Back page South Korea to issue fines for not wearing masks in public » Page 5 stripes.com Volume 79, No. 151 ©SS 2020 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2020 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas WAR ON TERRORISM US, Israel worked together to track, kill al-Qaida No. 2 BY MATTHEW LEE AND JAMES LAPORTA Associated Press WASHINGTON — The United States and Israel worked together to track and kill a senior al-Qaida operative in Iran this year, a bold intelligence operation by the allied nations that came as the Trump ad- ministration was ramping up pres- sure on Tehran. Four current and former U.S. offi- cials said Abu Mohammed al-Masri, al-Qaida’s No. 2, was killed by assas- sins in the Iranian capital in August. The U.S. provided intelligence to the Israelis on where they could find al- Masri and the alias he was using at the time, while Israeli agents carried out the killing, according to two of the officials. The two other officials confirmed al-Masri’s killing but could not provide specific details. Al-Masri was gunned down in a Tehran alley on Aug. 7, the anni- versary of the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Al- Masri was widely believed to have participated in the planning of those attacks and was wanted on terrorism charges by the FBI. -

20 YEARS of GRATITUDE: Home for the Holidays

ShelterBox Update December 2020 20 YEARS OF GRATITUDE: Home for the Holidays As the calendar year comes to a close and we reach the half-way point of the Rotary year, families all over the world are gathering in new ways to find gratefulness in being together, however that may look. Thank to our supporters in 2020, ShelterBox has been able to ensure that over 25,000 families have a home for the holidays. Home is the center of all that we do at ShelterBox, the same way as home is central to our lives, families, and communities. “For Filipinos, home – or ‘bahay’ as we call it – really is where the heart is. It’s the centre of our family life, our social life and very often our working life too. At Christmas especially, being able to get together in our own homes means everything to us.” – Rose Placencia, ShelterBox Operations Philippines The pandemic did not stop natural disasters from affecting the Philippines this year. Most recently a series of typhoons, including Typhoon Goni, the most powerful storm since 2013’s Typhoon Haiyan, devastated many communities in the region. In 2020, before Typhoon Goni struck, ShelterBox had responded twice to the Philippines, in response to the Taal Volcano eruption and Typhoon Vongfong. As we deploy in response to this new wave of tropical storm destruction, Alejandro and his family are just one of many recovering from Typhoon Vongfong who now have a home for the holidays. Typhoon Vongfong (known locally as Ambo) devastated communities across Eastern Samar in the Philippines earlier this year.