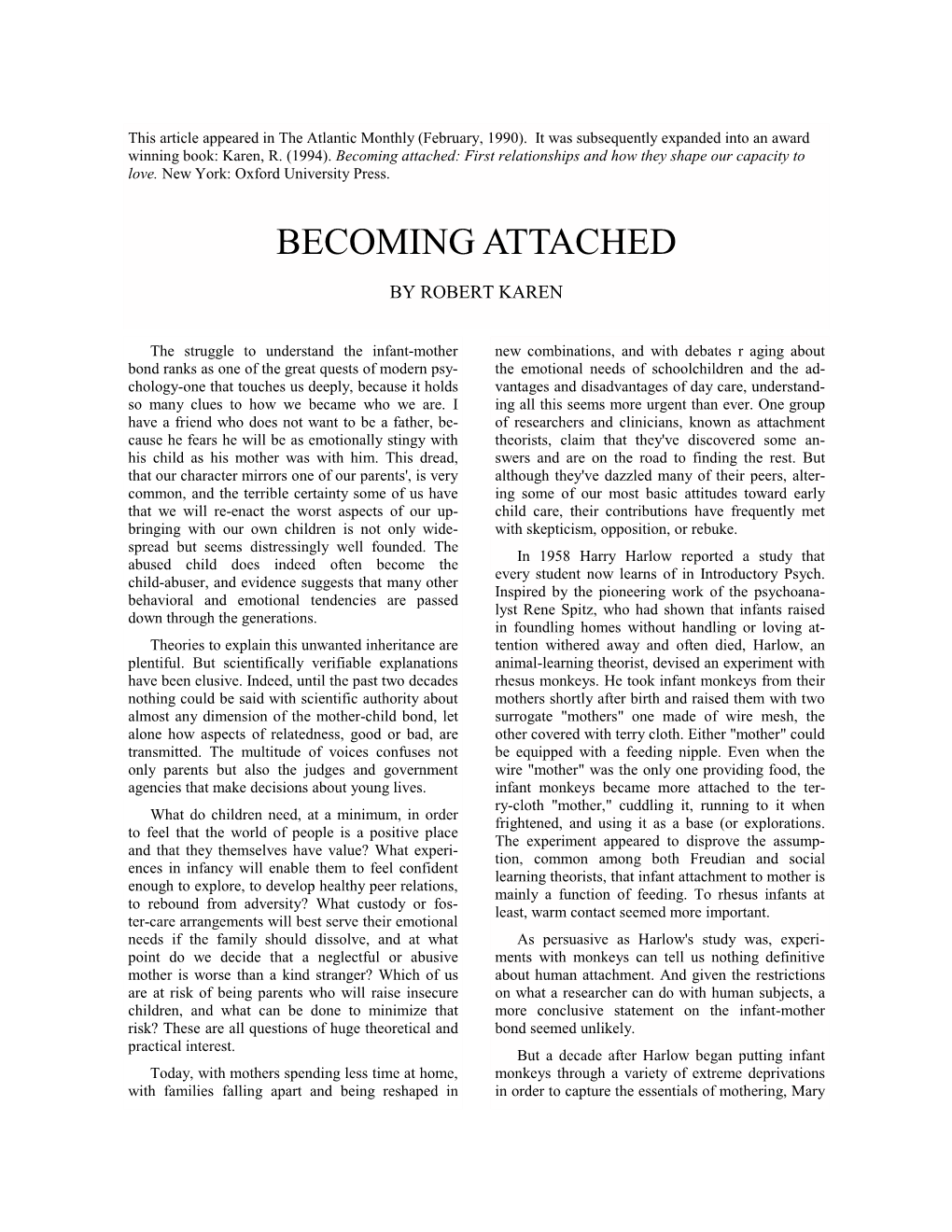

Becoming Attached: First Relationships and How They Shape Our Capacity to Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pregnancy, Maternal Unbound. Genesis of Filicide and Child Abuse María Teresa Sotelo Morales* 1President-Fundación En Pantalla Contra La Violencia Infantil, Mexico

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Research Article International Journal of pediatrics & Child Care Open Access Pregnancy, Maternal Unbound. Genesis of Filicide and Child Abuse María Teresa Sotelo Morales* 1President-Fundación En Pantalla Contra la Violencia Infantil, Mexico. Received: February 23, 2018; Accepted: March 06, 2018; Published: March 09, 2018 *Corresponding author: María Teresa Sotelo Morales, President-Fundación En Pantalla Contra la Violencia Infantil, Mexico, Tel: 55 56899263; E-mail: [email protected] Some academic studies, attribute to the depressive and / or Abstract This work supports the hypothesis that the origin of child abuse the depressive state, propitiates the detonation of the crime, and homicide, perpetrated by the mother, occurs during the gestational howeveranxiety state the inemotionally the mother disconnected a filicidal act. mothers It is recognized of their babythat stage, birth, and postnatal period, in women who do not created with depression and violence risk factors, commit the criminal during these stages, an affective bond with the baby / nasciturus, offense, hence, the lack of attachment during pregnancy, and alternately the woman, was suffering from some personality disorder most frequency depression, psychosis, anxiety, suicide attempts, low perinatal period, is the critical factor in child abuse or homicide. tolerance of frustrating, poor impulse control, among chaotic living With the purpose to test the feasibility of foreseeing, the conditions. risk factors in pregnant women trigger child abuse, we at the From 2009 to 2014, the FUPAVI’s foundation, applied a test of 221 foundation En Pantalla Contra la Violencia Infantil “FUPAVI”, women with a background of child abuse, 189 reported rejection of monitored a survey at the Obstetric Gynecology Hospital in pregnancy, and affective disconnection to the baby, 171 of them, were Toluca IMIEM, (2014) considering in advance to prove the theory under stress, and untreated depression, or other mental disorder. -

In Defense of Qualitative Changes in Development

In Defense of Qualitative Changes in Development The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Kagan, Jerome. 2008. “In Defense of Qualitative Changes in Development.” Child Development 79 (6): 1606–24. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01211.x. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37964397 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Child Development, November/December 2008, Volume 79, Number 6, Pages 1606 – 1624 In Defense of Qualitative Changes in Development Jerome Kagan Harvard University The balance between the preservation of early cognitive functions and serious transformations on these functions shifts across time. Piaget’s writings, which favored transformations, are being replaced by writings that emphasize continuities between select cognitive functions of infants and older children. The claim that young infants possess elements present in the older child’s concepts of number, physical impossibility, and object permanence is vulnerable to criticism because the inferences are based primarily on the single measure of change in looking time. It is suggested that investigators use unique constructs to describe phenomena observed in young infants that appear, on the surface, to resemble the psychological competences observed during later developmental stages. The primary goal of scientists working in varied allel in the motor profiles of the developing embryo disciplines is to explain how a phenomenon of (Hamburger, 1975). -

IVF Surrogacy: a Personal Perspective F 30

Australia´s National Infertility Network t e e IVF Surrogacy: h S t c a A Personal Perspective F 30 updated October 2011 In May 1988, Linda Kirkman gave birth to her niece, Alice, who was conceived from her mother (Linda’s sister) Maggie’s egg, fertilised by sperm from a donor. Maggie had no uterus and her husband, Sev, had no sperm. It was the first example in Australia (and one of the first in the world) of IVF surrogacy. Linda doesn’t call herself a ‘surrogate’ because she doesn’t feel that she is a substitute for anyone; she is a gestational mother. By the time Linda’s pregnancy was con- what would happen during IVF, such if she felt unable to proceed or couldn’t rmed, in October 1987, the family as whether Linda would ever go with relinquish the baby it would not be a had undertaken intense personal and Maggie to early morning clinic sessions, loss. eir relationship with Linda and interpersonal psychological work, many and whether Linda would have hormone Linda’s well-being were paramount. is attempts to negotiate with resistant eth- treatment or use her natural cycle. What was fundamental to ensuring that Linda ics committees, legal consultations at the if IVF failed? If Linda became pregnant, was able to make choices without duress, highest level in Victoria, and the rigorous would they accept screening tests for including backing out of the arrangement medical procedures that constitute IVF. abnormalities? How would complications at any point. e whole extended fam- ey were tremendously lucky to succeed with the pregnancy be managed? What ily was committed to Linda’s well-being, on their rst cycle. -

Witnessed Intimate Partner Abuse and Later Perpetration: the Maternal Attachment Influence

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2021 Witnessed Intimate Partner Abuse and Later Perpetration: The Maternal Attachment Influence Kendra Lee Wiechart Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Developmental Psychology Commons, and the Social Work Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Kendra Wiechart has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Sharon Xuereb, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Jessica Hart, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Victoria Latifses, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2021 Abstract Witnessed Intimate Partner Abuse and Later Perpetration: The Maternal Attachment Influence by Kendra Wiechart MA, Tiffin University, 2014 BA, The Ohio State University, 2010 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Psychology Walden University May 2021 Abstract Witnessing intimate partner abuse (IPA) as a child is linked to later perpetration as an adult. Questions remain regarding why some men who witnessed abuse go on to perpetrate, while others do not. The influence maternal attachment has on IPA perpetration after witnessed IPA has not been thoroughly researched. -

Surrogacy and the Maternal Bond

‘A Nine-Month Head-Start’: The Maternal Bond and Surrogacy Katharine Dow University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK This article considers the significance of maternal bonding in people’s perceptions of the ethics of surrogacy. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in Scotland with people who do not have personal experience of surrogacy, it describes how they used this ‘natural’ concept to make claims about the ethics of surrogacy and compares these claims with their personal experiences of maternal bonding. Interviewees located the maternal bond in the pregnant woman’s body, which means that mothers have a ‘nine-month head-start’ in bonding with their children. While this valorises it, it also reproduces normative expectations about the nature and ethic of motherhood. While mothers are expected to feel compelled to nurture and care for their child, surrogate mothers are supposed to resist bonding with the children they carry. This article explores how interviewees drew on the polysemous nature of the maternal bond to make nuanced claims about motherhood, bonding and the ethics of surrogacy. Keywords: maternal bonding, surrogacy, nature, ethics, motherhood ‘A Nine-Month Head-Start’ One afternoon towards the end of my fieldwork in northeastern Scotland, I was sitting talking with Erin. I had spent quite some time with her and her family over the previous eighteen months and had got to know her well. Now, she had agreed to let me record an interview with her about her thoughts on surrogacy. While her daughter was at nursery school, we talked for a couple of hours – about surrogacy, but also about Erin’s personal experience of motherhood, which had come somewhat unexpectedly as she had been told that she was unlikely to conceive a child after sustaining serious abdominal injuries in a car accident as a teenager. -

On Class Differences and Early Development. SPONS AGENCY Carnegie Corp

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 044 167 PS 003 280 AUTHOR Kagan, Jerome TITLE On Class Differences and Early Development. SPONS AGENCY Carnegie Corp. of New York, N.Y.; National Inst. of Child Health and Human Development (NIH), Bethesda, Md. PUB DATE 28 Dec 69 NOTE 26p.; Expanded version of address presented at tiw.: meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Boston, Massachusetts, Dec. 28, 1969 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$1.40 DESCRIPTORS *Change Agents, *Child Development, Cognitive Development, Cross Sectional Studies, *Early Experience, Language Skills, Longitudinal Studies, Lower Class, Middle Class, Parent Child Relationship, *Parent Role, Self Concept, *Social Differences ABSTRACT There are seven major sets of differences between young children of different economic backgrounds. The middle class child, compared to the lower class child, generally exhibits: (1) better language comprehension and expression, (2) richer schema development, involving mental preparation for the unusual, (3) stronger attachment to the mother, making him more receptive to adoption of her values and prohibitions, (4) less impulsive action, (5) a better sense of his potential effectiveness,(6) more motivation for school defined tasks, and (7)greater exceptation of success at intellectual problems. Data from two studies are offered in support of some of these hypotheses. One, a longitudinal study of 140 white, middle and lower class involved observations of their reactions at 4, 8, 13, and 27 months of age to masks with scrambled facial features. The other, a cross sectional study of 60 white, 10-month-old middle and lower class infants involved home observations cf mother and child behaviors and labo. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Marshall, P. J. (2010). the Development of Emotion. Wiley

Advanced Review The development of emotion Peter J. Marshall∗ Given that they are responsible for much of the meaning that we attribute to our existence, emotions could be said to have a central role in the psychological life of humans. But given this fundamental level of significance, the construct of emotion remains poorly understood, with the field of emotion research being full of conflicting definitions and opposing theoretical perspectives. In this review, one particular aspect of research into emotion is considered: the development of emotion in infancy and early childhood. The development of the emotional life of the child has been the focus of a vast amount of research and theorizing, so in a brief review it is only possible to scratch the surface of this topic. Rather than any attempt at a comprehensive account, three perennial questions in theorizing and research on early emotional development will be considered. First, what develops in emotional development? Second, what is the relation of cognitive development to emotional development? Third, how has the study of early individual differences in emotion expression typically been approached? In relation to the first question, four theoretical approaches to emotional development are described. For the second question, the focus is on the relation of self-awareness to the development of emotion. Finally, for the third question, the use of temperament theory as a framework for understanding individual differences in emotion expression is examined. 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. WIREs Cogn Sci 2010 1 417–425 n the space of the first 3 years of life, the difficult questions which lie at the intersection of the Ideveloping human undergoes very dramatic changes developmental, affective, and cognitive sciences. -

The Effects of Prenatal Transportation on Postnatal

THE EFFECTS OF PRENATAL TRANSPORTATION ON POSTNATAL ENDOCRINE AND IMMUNE FUNCTION IN BRAHMAN BEEF CALVES A Thesis by DEBORAH M. PRICE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Thomas H. Welsh Jr. Co-Chair of Committee, Ronald D. Randel Committee Members, Sara D. Lawhon Jeffery A. Carroll Head of Department, H. Russell Cross August 2013 Major Subject: Physiology of Reproduction Copyright 2013 Deborah M. Price ABSTRACT Prenatal stressors have been reported to affect postnatal cognitive, metabolic, reproductive and immune functions. This study examined immune indices and function in Brahman calves prenatally stressed by transportation of their dams on d 60, 80, 100, 120 and 140 ± 5 d of gestation. Based on assessment of cow’s temperament and their reactions to repeated transportation it was evident that temperamental cows displayed greater pre-transport cortisol (P < 0.0001) and glucose (P < 0.03) concentrations, and habituated slower to the stressor compared to cows of calm and intermediate temperament. Serum concentration of cortisol at birth was greater (P < 0.03) in prenatally stressed versus control calves. Total and differential white blood cell counts and serum cortisol concentration in calves from birth through the age of weaning were determined. We identified a sexual dimorphism in neutrophil cell counts at birth (P = 0.0506) and cortisol concentration (P < 0.02) beginning at 14 d of age, with females having greater amounts of both. Whether weaning stress differentially affected cell counts, cortisol concentrations and neutrophil function of prenatally stressed and control male calves was examined. -

DECISION-MA KING in the CHILD's BEST INTERESTS Legal and Psychological Views of a Child's Best Interests on Parental Separation

DECISION-MA KING IN THE CHILD'S BEST INTERESTS Legal and psychological views of a child's best interests on parental separation David Matthew Roy Townend LL. B. Sheffield Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield for the degree of Doctor of PhilosophY' following work undertaken in the Faculty of Submitted, January 1993' To my family, and in memory of Vaughan Bevan 1952 - 1992 ;J Contents. Preface. vi Abstract. viii. List of Cases. x. List of Statutes. xix. Introduction: The Thesis and Its Context 1. Part One: The Law Relating to Separation and Children. 1.1 The statutory requirements: the welfare principle. 15. 1.2 The application of the welfare principle. 42. Part Two: The Institution of Separation Law: The development of out-of-court negotiation. 130. Part Three: The Practice of Separation Law. 3.1 Methodology. 179. 3.2 The Empirical Findings: a. Biographical: experience and training. 191. b. Your role in child custody and accessdisputes. 232. c. Type of client. 254. d. The best interests of the child. 288. 3.3 Conclusions. 343. Part Four: The Psychology of Separation Law. 4.1 The Empirical Findings Concerning Children and Parental Separation. 357. 4.2 Attachment theory: A Definition for the Child's Best Interests? 380. 4.3 The Resolution of Adult Conflict: A Necessary Conclusion. 390. Appendices: A. 1 Preliminary Meetings. 397. A. 2 The Questionnaire. 424. A. 3 Observations. 440. A. 4 Data-tables. 458. Bibliography. V Preface. This work has only been possible because of other people, and I wish to thank them. My interest in this area. -

Comrade Britney and the Critical Potential of Marxist Memeing

41 Comrade Britney and the Critical Potential of Marxist Memeing Contemporary Matters Journal – Issue #3 42 Comrade Britney and the Critical Potential of Marxist Memeing by Sophie Publig “It’s comrade Britney, bitch” is written in pink pseudo-cyrillic letters over a red background.¹ In the center of the image, we see the famous counterfeits that form the classic genealogy of Marxist thinkers: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Britney Spears. Wait, Britney Spears, US-American pop hit machine since the late 1990s? If she never struck you as a thinker of the proletariat, perhaps it’s time to go through her lyrical œuvre that has not been short of making labor a subject of discussion. Take, for example, the 2013 electro pop classic “Work B*tch”: You want a hot body? You want a Bugatti? You want a Maserati? You better work bitch You want a Lamborghini? Sippin’ martinis? Look hot in a bikini? You better work bitch You wanna live fancy? Live in a big mansion? Party in France? 1 You better work bitch, you better work bitch It’s Comrade Britney, Bitch meme, from: KnowYourMeme, 2020, You better work bitch, you better work bitch URL: https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/001/800/632/6fd.png (17.1.2021). Now get to work bitch!² 2 Performed over an up-tempo beat using an instructor-like tone, Britney is indoctrinating us Genius, URL: https://genius.com/Britney-spears-work-bitch-lyrics (17.1.2021). with the classic neoliberal myth: the more you work, the more you can consume. -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M.