Syntactic Annotation of Spoken Utterances: a Case Study on the Czech Academic Corpus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adapting to Trends in Language Resource Development: a Progress

Adapting to Trends in Language Resource Development: A Progress Report on LDC Activities Christopher Cieri, Mark Liberman University of Pennsylvania, Linguistic Data Consortium 3600 Market Street, Suite 810, Philadelphia PA. 19104, USA E-mail: {ccieri,myl} AT ldc.upenn.edu Abstract This paper describes changing needs among the communities that exploit language resources and recent LDC activities and publications that support those needs by providing greater volumes of data and associated resources in a growing inventory of languages with ever more sophisticated annotation. Specifically, it covers the evolving role of data centers with specific emphasis on the LDC, the publications released by the LDC in the two years since our last report and the sponsored research programs that provide LRs initially to participants in those programs but eventually to the larger HLT research communities and beyond. creators of tools, specifications and best practices as well 1. Introduction as databases. The language resource landscape over the past two years At least in the case of LDC, the role of the data may be characterized by what has changed and what has center has grown organically, generally in response to remained constant. Constant are the growing demands stated need but occasionally in anticipation of it. LDC’s for an ever-increasing body of language resources in a role was initially that of a specialized publisher of LRs growing number of human languages with increasingly with the additional responsibility to archive and protect sophisticated annotation to satisfy an ever-expanding list published resources to guarantee their availability of the of user communities. Changing are the relative long term. -

Characteristics of Text-To-Speech and Other Corpora

Characteristics of Text-to-Speech and Other Corpora Erica Cooper, Emily Li, Julia Hirschberg Columbia University, USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract “standard” TTS speaking style, whether other forms of profes- sional and non-professional speech differ substantially from the Extensive TTS corpora exist for commercial systems cre- TTS style, and which features are most salient in differentiating ated for high-resource languages such as Mandarin, English, the speech genres. and Japanese. Speakers recorded for these corpora are typically instructed to maintain constant f0, energy, and speaking rate and 2. Related Work are recorded in ideal acoustic environments, producing clean, consistent audio. We have been developing TTS systems from TTS speakers are typically instructed to speak as consistently “found” data collected for other purposes (e.g. training ASR as possible, without varying their voice quality, speaking style, systems) or available on the web (e.g. news broadcasts, au- pitch, volume, or tempo significantly [1]. This is different from diobooks) to produce TTS systems for low-resource languages other forms of professional speech in that even with the rela- (LRLs) which do not currently have expensive, commercial sys- tively neutral content of broadcast news, anchors will still have tems. This study investigates whether traditional TTS speakers some variance in their speech. Audiobooks present an even do exhibit significantly less variation and better speaking char- greater challenge, with a more expressive reading style and dif- acteristics than speakers in found genres. By examining char- ferent character voices. Nevertheless, [2, 3, 4] have had suc- acteristics of f0, energy, speaking rate, articulation, NHR, jit- cess in building voices from audiobook data by identifying and ter, and shimmer in found genres and comparing these to tra- using the most neutral and highest-quality utterances. -

100000 Podcasts

100,000 Podcasts: A Spoken English Document Corpus Ann Clifton Sravana Reddy Yongze Yu Spotify Spotify Spotify [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Aasish Pappu Rezvaneh Rezapour∗ Hamed Bonab∗ Spotify University of Illinois University of Massachusetts [email protected] at Urbana-Champaign Amherst [email protected] [email protected] Maria Eskevich Gareth J. F. Jones Jussi Karlgren CLARIN ERIC Dublin City University Spotify [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ben Carterette Rosie Jones Spotify Spotify [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Podcasts are a large and growing repository of spoken audio. As an audio format, podcasts are more varied in style and production type than broadcast news, contain more genres than typi- cally studied in video data, and are more varied in style and format than previous corpora of conversations. When transcribed with automatic speech recognition they represent a noisy but fascinating collection of documents which can be studied through the lens of natural language processing, information retrieval, and linguistics. Paired with the audio files, they are also a re- source for speech processing and the study of paralinguistic, sociolinguistic, and acoustic aspects of the domain. We introduce the Spotify Podcast Dataset, a new corpus of 100,000 podcasts. We demonstrate the complexity of the domain with a case study of two tasks: (1) passage search and (2) summarization. This is orders of magnitude larger than previous speech corpora used for search and summarization. Our results show that the size and variability of this corpus opens up new avenues for research. -

Named Entity Recognition in Question Answering of Speech Data

Proceedings of the Australasian Language Technology Workshop 2007, pages 57-65 Named Entity Recognition in Question Answering of Speech Data Diego Molla´ Menno van Zaanen Steve Cassidy Division of ICS Department of Computing Macquarie University North Ryde Australia {diego,menno,cassidy}@ics.mq.edu.au Abstract wordings of the same information). The system uses symbolic algorithms to find exact answers to ques- Question answering on speech transcripts tions in large document collections. (QAst) is a pilot track of the CLEF com- The design and implementation of the An- petition. In this paper we present our con- swerFinder system has been driven by requirements tribution to QAst, which is centred on a that the system should be easy to configure, extend, study of Named Entity (NE) recognition on and, therefore, port to new domains. To measure speech transcripts, and how it impacts on the success of the implementation of AnswerFinder the accuracy of the final question answering in these respects, we decided to participate in the system. We have ported AFNER, the NE CLEF 2007 pilot task of question answering on recogniser of the AnswerFinder question- speech transcripts (QAst). The task in this compe- answering project, to the set of answer types tition is different from that for which AnswerFinder expected in the QAst track. AFNER uses a was originally designed and provides a good test of combination of regular expressions, lists of portability to new domains. names (gazetteers) and machine learning to The current CLEF pilot track QAst presents an find NeWS in the data. The machine learn- interesting and challenging new application of ques- ing component was trained on a develop- tion answering. -

Reducing Out-Of-Vocabulary in Morphology to Improve the Accuracy in Arabic Dialects Speech Recognition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Reducing Out-of-Vocabulary in Morphology to Improve the Accuracy in Arabic Dialects Speech Recognition by Khalid Abdulrahman Almeman A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Computer Science The University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis has two aims: developing resources for Arabic dialects and improving the speech recognition of Arabic dialects. Two important components are considered: Pro- nunciation Dictionary (PD) and Language Model (LM). Six parts are involved, which relate to finding and evaluating dialects resources and improving the performance of sys- tems for the speech recognition of dialects. Three resources are built and evaluated: one tool and two corpora. The methodology that was used for building the multi-dialect morphology analyser involves the proposal and evaluation of linguistic and statistic bases. We obtained an overall accuracy of 94%. The dialect text corpora have four sub-dialects, with more than 50 million tokens. -

Detection of Imperative and Declarative Question-Answer Pairs in Email Conversations

Detection of Imperative and Declarative Question-Answer Pairs in Email Conversations Helen Kwong Neil Yorke-Smith Stanford University, USA SRI International, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract is part of an effort to endow an email client with a range of usable smart features by means of AI technology. Question-answer pairs extracted from email threads Prior work that studies the problems of question identifi- can help construct summaries of the thread, as well cation and question-answer pairing in email threads has fo- as inform semantic-based assistance with email. cused on interrogative questions, such as “Which movies do Previous work dedicated to email threads extracts you like?” However, questions are often expressed in non- only questions in interrogative form. We extend the interrogative forms: declarative questions such as “I was scope of question and answer detection and pair- wondering if you are free today”, and imperative questions ing to encompass also questions in imperative and such as “Tell me the cost of the tickets”. Our sampling from declarative forms, and to operate at sentence-level the well-known Enron email corpus finds about one in five fidelity. Building on prior work, our methods are questions are non-interrogative in form. Further, previous based on learned models over a set of features that work for email threads has operated at the paragraph level, include the content, context, and structure of email thus potentially missing more fine-grained conversation. threads. For two large email corpora, we show We propose an approach to extract question-answer pairs that our methods balance precision and recall in ex- that includes imperative and declarative questions. -

Low-Cost Customized Speech Corpus Creation for Speech Technology Applications

Low-cost Customized Speech Corpus Creation for Speech Technology Applications Kazuaki Maeda, Christopher Cieri, Kevin Walker Linguistic Data Consortium University of Pennsylvania 3600 Market St., Suite 810 Philadelphia, 19104 PA, U.S.A. fmaeda, ccieri, [email protected] Abstract Speech technology applications, such as speech recognition, speech synthesis, and speech dialog systems, often require corpora based on highly customized specifications. Existing corpora available to the community, such as TIMIT and other corpora distributed by LDC and ELDA, do not always meet the requirements of such applications. In such cases, the developers need to create their own corpora. The creation of a highly customized speech corpus, however, could be a very expensive and time-consuming task, especially for small organizations. It requires multidisciplinary expertise in linguistics, management and engineering as it involves subtasks such as the corpus design, human subject recruitment, recording, quality assurance, and in some cases, segmentation, transcription and annotation. This paper describes LDC's recent involvement in the creation of a low-cost yet highly-customized speech corpus for a commercial organization under a novel data creation and licensing model, which benefits both the particular data requester and the general linguistic data user community. 1. Introduction sented each of four regional groups, three age groups and The Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC) is a non-profit or- two gender groups. To meet this first challenge, we con- ganization, whose primary mission is to support educa- ducted a recruitment effort to meet these demographic re- tion, research and technology development in language- quirements. In order to ensure that recordings are consis- related disciplines. -

Arabic Language Modeling with Stem-Derived Morphemes for Automatic Speech Recognition

ARABIC LANGUAGE MODELING WITH STEM-DERIVED MORPHEMES FOR AUTOMATIC SPEECH RECOGNITION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ilana Heintz, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Linguistics The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Prof. Chris Brew, Co-Adviser Prof. Eric Fosler-Lussier, Co-Adviser Prof. Michael White c Copyright by Ilana Heintz 2010 ABSTRACT The goal of this dissertation is to introduce a method for deriving morphemes from Arabic words using stem patterns, a feature of Arabic morphology. The motivations are three-fold: modeling with morphemes rather than words should help address the out-of- vocabulary problem; working with stem patterns should prove to be a cross-dialectally valid method for deriving morphemes using a small amount of linguistic knowledge; and the stem patterns should allow for the prediction of short vowel sequences that are missing from the text. The out-of-vocabulary problem is acute in Modern Standard Arabic due to its rich morphology, including a large inventory of inflectional affixes and clitics that combine in many ways to increase the rate of vocabulary growth. The problem of creating tools that work across dialects is challenging due to the many differences between regional dialects and formal Arabic, and because of the lack of text resources on which to train natural language processing (NLP) tools. The short vowels, while missing from standard orthography, provide information that is crucial to both acoustic modeling and grammatical inference, and therefore must be inserted into the text to train the most predictive NLP models. -

Speech to Text to Semantics: a Sequence-To-Sequence System for Spoken Language Understanding

Speech to Text to Semantics: A Sequence-to-Sequence System for Spoken Language Understanding John Dodson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Gina-Anne Levow, Chair Philip Borawski Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Linguistics c Copyright 2020 John Dodson University of Washington Abstract Speech to Text to Semantics: A Sequence-to-Sequence System for Spoken Language Understanding John Dodson Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Gina-Anne Levow Linguistics Spoken language understanding entails both the automatic transcription of a speech utter- ance and the identification of one or more semantic concepts being conveyed by the utterance. Traditionally these systems are domain specific and target industries like travel, entertain- ment, and home automation. As such, many approaches to spoken language understanding solve the task of filling predefined semantic slots, and cannot generalize to identify arbitrary semantic roles. This thesis addresses the broader question of how to extract predicate-argument frames from a transcribed speech utterance. I describe a sequence-to-sequence system for spoken language understanding through shallow semantic parsing. Built using a modification of the OpenSeq2Seq toolkit, the system is able to perform speech recognition and semantic parsing in a single end-to-end flow. The proposed system is extensible and easy to use, allowing for fast iteration on system parameters and model architectures. The system is evaluated through two experiments. The first experiment performs a speech to text to semantics transformation and uses n-best language model rescoring to generate the best transcription sequence. -

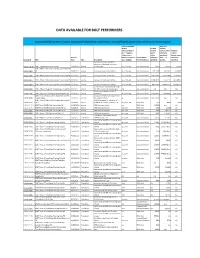

Data Available for Bolt Performers

DATA AVAILABLE FOR BOLT PERFORMERS Data Created During BOLT; corpora automatically distributed to performers. Contact [email protected] to obtain any missing corpora Source Language cmn data Where arz data volume Relevant/Known volume (words unless eng data (arz = Egyptian (words otherwise volume Arabic; cmn = unless specified; 1 (words unless Release Mandarin Chinese; Genre Where otherwise char = 1.5 otherwise Catalog ID Title Date Type Description eng = English) Relevant/Known specified) words) specified) Discussion forums sample for eliciation of feedback on format, LDC2011E115 BOLT ‐ Sample Discussion Forums 12/22/2011 Source structure, etc. arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 67815 106130 142491 BOLT ‐ Phase 1 Discussion Forums Source Data R1 LDC2012E04 V2 3/29/2012 Source Discussion forums source data arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 33871338 36244922 29658002 LDC2012E16 BOLT ‐ Phase 1 Discussion Forums Source Data R2 3/22/2012 Source Discussion forum source data arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 118519987 264314806 273078669 LDC2012E21 BOLT ‐ Phase 1 Discussion Forums Source Data R3 4/24/2012 Source Discussion forums source data arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 127832646 279763913 282588862 LDC2012E54 BOLT ‐ Phase 1 Discussion Forums Source Data R4 5/31/2012 Source Discussion forums source data arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 368199350 838056761 676989452 List of threads rejected during triage LDC2012E62 BOLT ‐ Phase 1 Rejected Training Data Thread IDs 6/1/2012 Source for BOLT translation training data n/a discussion forum n/a n/a n/a List of source documents for IR LDC2012E82 BOLT Phase 1 IR Eval Source Data Document List 6/29/2012 Source evaluation arz, cmn, eng discussion forum 400036669 400168661 400219116 BOLT Phase 2 IR Source Data Document List and Discussion forum source documents LDC2013E08 Sample Query 1/31/2012 Source for support of P2 IR arz discussion forum 616719471 n/a n/a BOLT Phase 2 SMS and Chat Sample Source Data SMS/chat sample for eliciation of LDC2013E10 V1.1 3/5/2013 Source feedback on format, structure, etc. -

The Workshop Programme

The Workshop Programme Monday, May 26 14:30 -15:00 Opening Nancy Ide and Adam Meyers 15:00 -15:30 SIGANN Shared Corpus Working Group Report Adam Meyers 15:30 -16:00 Discussion: SIGANN Shared Corpus Task 16:00 -16:30 Coffee break 16:30 -17:00 Towards Best Practices for Linguistic Annotation Nancy Ide, Sameer Pradhan, Keith Suderman 17:00 -18:00 Discussion: Annotation Best Practices 18:00 -19:00 Open Discussion and SIGANN Planning Tuesday, May 27 09:00 -09:10 Opening Nancy Ide and Adam Meyers 09:10 -09:50 From structure to interpretation: A double-layered annotation for event factuality Roser Saurí and James Pustejovsky 09:50 -10:30 An Extensible Compositional Semantics for Temporal Annotation Harry Bunt, Chwhynny Overbeeke 10:30 -11:00 Coffee break 11:00 -11:40 Using Treebank, Dictionaries and GLARF to Improve NomBank Annotation Adam Meyers 11:40 -12:20 A Dictionary-based Model for Morpho-Syntactic Annotation Cvetana Krstev, Svetla Koeva, Du!ko Vitas 12:20 -12:40 Multiple Purpose Annotation using SLAT - Segment and Link-based Annotation Tool (DEMO) Masaki Noguchi, Kenta Miyoshi, Takenobu Tokunaga, Ryu Iida, Mamoru Komachi, Kentaro Inui 12:40 -14:30 Lunch 14:30 -15:10 Using inheritance and coreness sets to improve a verb lexicon harvested from FrameNet Mark McConville and Myroslava O. Dzikovska 15:10 -15:50 An Entailment-based Approach to Semantic Role Annotation Voula Gotsoulia 16:00 -16:30 Coffee break 16:30 -16:50 A French Corpus Annotated for Multiword Expressions with Adverbial Function Eric Laporte, Takuya Nakamura, Stavroula Voyatzi -

Linkedsaeima

LinkedSaeima: Linked Open Dataset of Latvia's Parliamentary Debates Uldis Bojārs, Roberts Darģis Uldis Lavrinovičs, Pēteris Paikens LinkedSaeima The corpus of Latvia's parliamentary debates • ... published as Linked Data • ... based on the LinkedEP * model hGp://da.saeima.korpuss.lv/ MoJvaon: Offering new ways how to look at the parliament debates and how explore them. * van Aggelen, A., Hollink, L., Kemman, M., Kleppe, M., Beunders, H.: The debates of the European parliament as linked open data. SemanJc Web, 8(2), 271–281 (2017) Corpus of the Saeima Saeima is the Parliament of the Republic of Latvia. The Corpus of the Saeima is a collecJon of transcripJons of parliamentary debates from 7 parliamentary terms (5th–12th) covering years 1993 – 2017. It contains 38 million tokens and 497 thousand uGerances (speeches). Enrichment Layers Available datasets • English translaon • Bonito corpus browser • Named en:es • Universal Dependencies format • Morphological and syntacJcal • LinkedSaeima (Linked Data) annotaons Bonito corpus browser (NoSketch engine) Text corpus user interface provides a powerful query system. Queries can include words, lemmas, morphological tags and meta data. hp://da.saeima.korpuss.lv/nosketch • Triple Paern fragments • Linked Data (LodView) • RDf dump (Turtle RDf) Named Entity Linking MenJons of named enJJes (persons, organizaons, locaons) are linked to Wikidata knowledge base idenJfiers. • Preprocessing: Wikidata enJty aliases are extended with Latvian morphological inflecJons and automacally generated alternate labels (for person and organizaon names) • Linking is performed by matching speech text fragments with enJty labels (choosing the most specific match). The Corpus of the Saeima contains 393 thousand menJons of approx. 3 thousand unique enJJes. 33% of speeches contain enJty menJons.