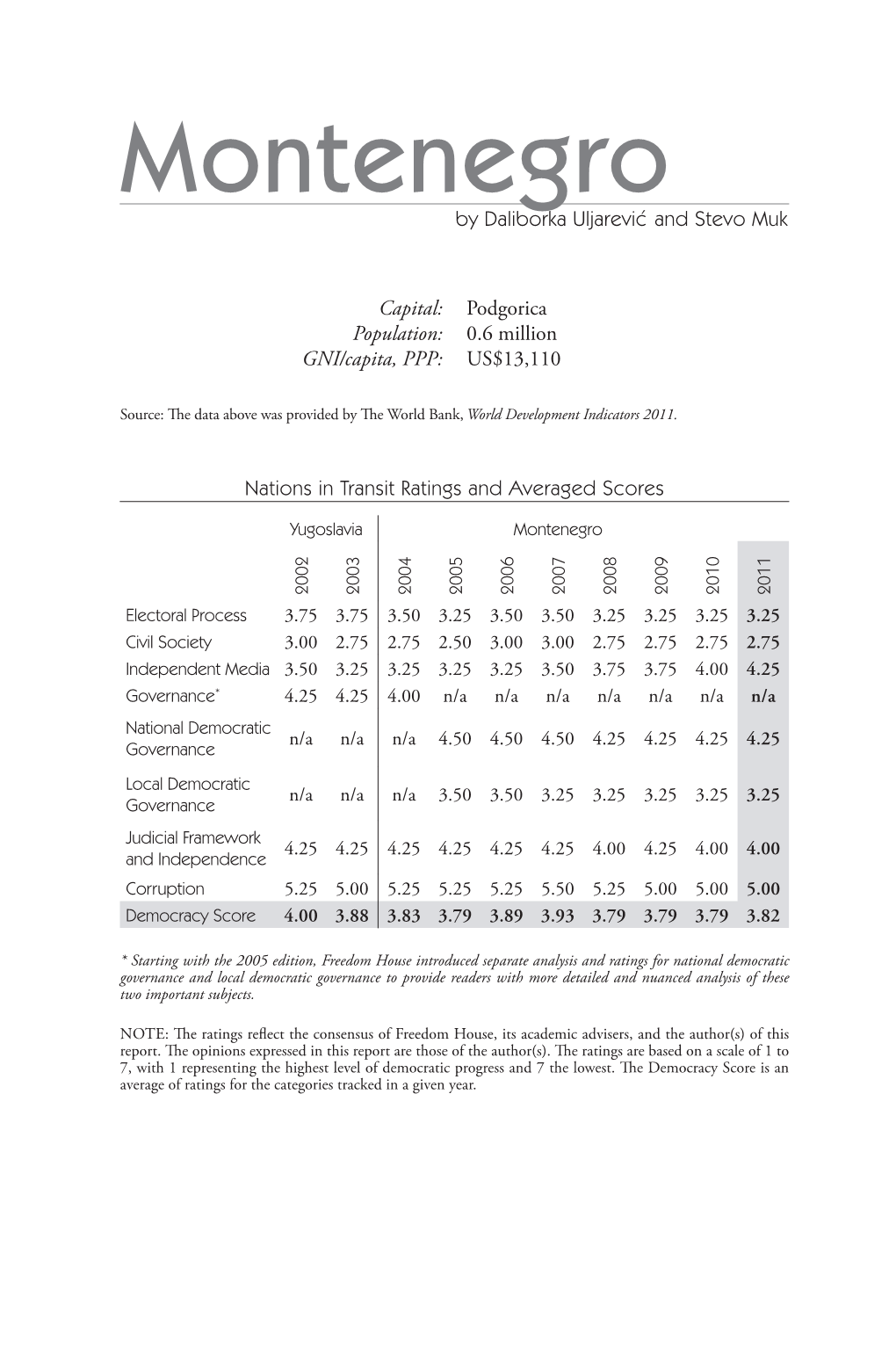

Montenegro by Daliborka Uljarevic´ and Stevo Muk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“MLADOST” BIJELA This Analysis Was Carried out in March 2014 F

ANALYSIS OF MEDIA REPORTING ON CHILDREN IN CHLDREN’S HOME “MLADOST” BIJELA This analysis was carried out in March 2014 for the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare of Montenegro and UNICEF by Ms. Zdenka Jagarinec, Slovenian journalist and editor with more than 20 years of experience, and Mr. Ugljesa Jankovic teaching assistant at the Faculty of Political Science in Podgorica. The analysis and assessment of media reporting on children in the Children’s Home “Mladost” in Bijela was made based on 207 media reports published in Montenegro in the period between1st December 2013 and 31st January 2014. The analysis covered media releases from six daily newspapers – Dnevne novine, Vijesti, Pobjeda, Dan, Večernje novosti and Blic, one weekly magazine - Monitor, three portals – Cafe del Montenegro, Portal Analitika and Bankar.me, and four TV agencies – TVCG, TV Prva, TV Vijesti and TV Pink. The names of media agencies and donors/visitors to “Mladost” in the context of specific media reports have been removed from the text. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ANALYSIS OF MEDIA EXPOSURE OF CHILDREN IN THE CHILDREN’S 3 HOME “MLADOST”, BIJELA I. Statistical analysis of media reporting about children from the Children’s Home 3 “Mladost”, Bijela II. Analysis of media reporting from the aspect of rights of the child 6 III. The context of media reports about children from the Children’s Home 10 “Mladost”, Bijela CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 14 ANNEXES 17 Annex I: Excerpts from Laws, Documents and Guidelines 17 Annex II: Case study Kolasin 21 Annex III: Examples of reporting about children in Slovenia 23 2 ANALYSIS OF MEDIA EXPOSURE OF CHILDREN IN THE CHILDREN’S HOME “MLADOST”, BIJELA Media have an important impact on the social position of children. -

Centralno Groblje Golubovci“

Glavni grad - Podgorica LSL „Centralno Groblje Golubovci“ NACRT PLANA Naručilac: Agencija za razvoj i izgradnju Podgorice, d.o.o. Obrađivač: Winsoft d.o.o. i CAU d.o.o. Podgorica, septembar 2016. Naslov dokumenta: LSL „Centralno Groblje Golubovci“ Naručilac: Agencija za izgradnju i razvoj Podgorice, Ugovor broj 2608 od 21.03.2016.god. Odluka o donošenju: Obrađivač: WINsoft d.o.o. (lic. br. 01-947/2) i CAU – Centar za arhitekturu i urbanizam d.o.o. (lic. br. 01-187/2) _________________________________________________________________________ RADNI TIM Rukovodilac izrade plana Predrag Bulajić, dipl.inž.el. (lic.br. 01-645/2) Odgovorni planer Srđan Pavićević, spec.arh. (lic.br. 01-841/2) Saobraćajna infrastruktura Nada Brajović, dipl.inž.građ. (lic.br. 10-4429/1) Elektroenergetska infrastruktura Milanko Džuver, dipl.inž.el. (lic.br. 01-129/2) Telekomunikaciona infrastruktura Predrag Bulajić, dipl.inž.el. (lic.br. 01-645/2) Zoran Marković, dipl.inž.el (lic.br. 05-3607/1-07) Hidrotehnička infrastruktura Irena Raonić, dipl.inž.građ. (lic.br 01-950/2) Šumarstvo i pejzažno uređenje Radosav Nikčević,dipl.inž.šum.(lic.br 10-3808/1) Nađa Skrobanović, dipl.inž.pa Geodezija: mr. Miloš Matković (lic. br. 01-11/3) Životna sredina dr. Vasilije Radulović, dipl.inž.geol. Privreda i društveni servisi Ivana Janković, dipl.mat (lic.br. 01-644/2) Baza podataka i GIS Ivana Janković, dipl.mat (lic.br. 01-644/2) Ivo Minić, dipl.mat. Tehnička obrada Igor Vlahović, inž.rač. Saša Šljivančanin Podgorica, IX 2016. Za obrađivača Predrag Bulajić _______________________ 3 4 SADRŽAJ 1. UVOD .......................................................................................................................... 17 1.1. Granica i površina zahvata ................................................................................... -

Footprint of Financial Crisis in the Media: Montenegro

Footprint of Financial Crisis in the Media MONTENEGRO country report Compiled by Daniela Šeferovi č Commissioned by Open Society Institute December 2009 FOOTPRINT OF FINANCIAL CRISIS IN THE MEDIA Introduction Montenegro secured internationally recognised statehood in 2006, and the post-independence period saw dynamic rates of economic growth accompanied by a surge of investments, turning the economy into the most dynamic in Europe. The World Bank report Beyond the Peak: Growth Policies and Fiscal Constraints—Public Expenditure and Institutional Review stated that Montenegro was one of the world’s fastest growing non-oil economies in 2007. This period was characterised by a great dynamic in the capital and property markets, as well as a significant increase in public revenues, accompanied by a rise in surplus and state deposits. The side-effects of this economic growth were overheating of the economy, inflation and high balance-of-payments deficit. Such trends were unsustainable in the long run. From the last quarter of 2008, negative trends became more visible, resulting in the downfall of the capital market and problems in the construction and banking industries. Domestic banks were unable to lend to the private sector, which left one-quarter of companies struggling with liquidity problems. General state of the media sector Not even the period of the most dynamic economic growth made the media business profitable in Montenegro. In 2006/7 only a handful of media companies, including Vijesti, Dan, TV Pink and TV IN, which was then taken over by a Slovenian investment group, showed market vitality. A certain number of private media were surviving thanks to the help of foreign donors, but this income did not cover all costs and started becoming less available. -

Monitoring-Medija-35Mm.Pdf

MONITORING MEDIJA SADRŽAJ ZAKONSKI OKVIR ..................................................................................................................................................................3 METODOLOGIJA ....................................................................................................................................................................6 NAJZNAČAJNIJI NALAZI ISTRAŽIVANJA ..........................................................................................................................7 Novinski prostor posvećen djeci/mladima ..............................................................................................................................7 Dubina obrađenih tema koje se tiču djece/mladih................................................................................................................9 Objektivnost izvještavanja o djeci/mladima..........................................................................................................................10 Senzacionalizam u izvještavanju o djeci/mladima..............................................................................................................12 Teme koje se tiču djece/mladih ..................................................................................................................................................16 Fotografije u izvještavanju o djeci/mladima..........................................................................................................................16 Pravo na privatnost -

Wus Austria Podgorica Office Media Report 2008

WUS AUSTRIA PODGORICA OFFICE MEDIA REPORT 2008 16.12.2008 Life is beautiful (TV ATLAS) Sep. 2008 Studentski magazin "Tribune" - Organizacija WUS Austria i Univerzitet Crne Gore nastavljaju dosadašnju uspješnu saradnju , "Konkretizacija dogovorenih projekata" English translation: Student magazine "Tribune" - Organisation WUS Austria and the University of Montenegro continue successful cooperation, "Concrete realization of agreed projects" May 2008 Studentski magazin "Tribune" - Nevladina organizacija WUS Austria je ponudila mogućnost studentima da teorijska znanja primijene praktično, "Završeno studentsko takmičenje Montenegro Case Challenge" English translation: Student magazine "Tribune" – Non-governmental organisation WUS Austria offered students the possibility to put their theoretical knowledge into practice, "Student Competition Montenegro Case Challenge Completed" Studentski časopis "Projectis" - Razgovarali smo sa Stefanom Aleksićem, članom studentske organizacije "Proprojectis" i studentom druge godine ekonomije "Studenti - glavna pokretačka snaga" English translation: Student magazine "Projectis" - We spoke with Stefan Aleksic, member of the student organisation "Proprojectis" and student of the second year at the Faculty of Economics "Students – the main driving force" 14.05.2008 Dnevne novine "Dan" - Promovisana knjiga o demokratiji u istočnoj i centralnoj Evropi "Srbija samo promijenila vladara" English translation: Daily Newspaper "Dan" - Book on democracy in Eastern and Central Europe promoted "Serbia only changed the ruling -

Montenegro Guidebook

MONTENEGRO PREFACE Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro, lies in a broad plain crossed by five rivers and surrounded by mountains, just 20 kilometers from the Albanian border. The city has a population of around 180,000 people. Bombed into rubble during World War II, Podgorica was rebuilt into a modern urban center, with high-rise apartment buildings and new office and shopping developments. While the latest Balkan war had a low impact on the physical structures, the economic sanctions had a devastating effect on employment and infrastructure. With the help of foreign investment, urban renewal is evident throughout the city, but much of it may still appear run down. Podgorica has a European-style town center with a pedestrian- only walking street (mall) and an assortment of restaurants, cafes, and boutiques. To many, its principal attraction is as a base for the exploration of Montenegro’s natural beauty, with mountains and wild countryside all around and the stunning Adriatic coastline less than an hour away. This is a mountainous region with barren moorlands and virgin forests, with fast-flowing rivers and picturesque lakes; Skadar Lake in particular is of ecological significance. The coastline is known for its sandy beaches and dramatic coves: for example, Kotor – the city that is protected by UNESCO and the wonderful Cathedral of Saint Typhoon; the unique baroque Perast; Saint George and Our Lady of the Rock islands – all locations that tell a story of a lasting civilization and the wealth of the most wonderful bay in the world. The area around the city of Kotor is a UNESCO World Heritage site for its natural beauty and historic significance. -

Montenegro: IREX Media Sustainability Index 2017

Journalism remains a battleground, with deep divisions rooted in commercial and political problems. Few of Montenegro’s 73 media outlets distance themselves from political polarization. MONTENEGRO ii MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2017 introduction OVERALL SCORE: 2.04 MONTENEGRO In 2016, Montenegro was marked by political instability, a government crisis, and a parliamentary election. Economic growth at 3 percent was promising but high public debt and 19 percent unemployment still dog the country’s recovery. The European Union (EU) and NATO accession process continue to unfold: Montenegro has opened 24 out of the 35 Accession INegotiation Chapters required for admission to the EU and it is quite realistic to expect that next year Montenegro will be the 29th NATO member-state. While two-thirds of citizens support accession to the EU and a narrow majority also in favor of joining NATO, Serbian nationalists, bolstered by strong Russian support, oppose the process along with the influential Serbian Orthodox Church. Conflict within the ruling coalition, between the dominant political party (the Democratic Party of Socialists, or DPS) and its long-standing ally (the Socialist Democratic Party) resulted in an election on October 16. The DPS won again and, with allies from minority parties, the ruling bloc won 42 seats, while the opposition got 39. The election boasted a 73-percent voter turnout but also saw the arrest of 20 Serbian nationals. They were suspected of preparing a post-election terrorist attack in Montenegrin capital of Podgorica, abetted by two Russian nationals. Subsequently, the opposition still has not conceded the election, although a majority of local electoral observers and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe said that the election was fair, democratic, and free. -

Tiče Me Se – Mjesečni Izvještaj Br. 02

PARLAMENTARNITI IZBORIČ‐ 16.E OKTOBAR ME 2016. SEMJESEČNI IZVJEŠTAJ Monitoring izborne kampanje medijicivilno društvogovor mržnje Koordinatori izvještaja: Zoran Vujičić i Boris Raonić PARLAMENTARNI IZBORI ‐ 16. OKTOBAR 2016. MJESEČNI IZVJEŠTAJ Izvještaj koji je pred Vama namijenjen je prvenstveno građanima Crne Gore koji imaju pravo glasa i predstavlja doprinos NF Građanska alijansa objektivnijem informisanju glasača i njihovoj aktivnijoj političkoj participaciji. Izvještaj se objavljuje na mjesečnom nivou i sastoji se od tri cjeline: Monitoring medija (RTCG, TV Prva, TV Pink M, TV Vijesti, TV Atlas, dnevne novine Dan, Vijesti, Pobjeda, Dnevne novine); Građansko nadgledanje izbora; Pravo na slobodu javnog okupljanja i govor mržnje. 1. MONITORING TV I ŠTAMPANIH MEDIJA Kvantitativno kvalitativna analiza sadržaja podrazumijeva prikupljanje tekstova iz četiri dnevne novine i priloga iz udarnih informativnih emisija pet televizijskih stanica sa nacionalnom pokrivenošću, te njihovo analiziranje na osnovu unaprijed zadate matrice. Analiza je sprovedena u periodu od 12.09.2016. do 12.10.2016. (uključujući i 12.10.) i obuhvatila je priloge centralnih informativnih emisija na pet glavnih televizija u Crnoj Gori (RTCG, Vijesti, Prva, Atlas i Pink M), kao i tekstove objavljene u: Pobjedi, Vijestima, Danu i Dnevnim novinama. Analiza je obuhvatila tekstove i priloge u kojima se pominju sve partije i koalicije. U toku drugog mjeseca trajanja analize objavljeno je čak 907 priloga u centralnim informativnim emisijama pet analiziranih televizija u kojima je pominjana neka od navedenih partija/koalicija (što je gotovo duplo više nego u prvom mjesecu) i 1.532 teksta u dnevnim novinama (porast za gotovo 10% tekstova u odnosu na prvi mjesec). Najviše priloga emitovala je RTCG - 296, slijede TV Vijesti sa 198, TV Prva sa 177 priloga i Pink M sa 163 priloga. -

Public Service Broadcasting in Montenegro

ANALITIKA Center for Social Research Working Paper 4/2017 Public Service Broadcasting in Montenegro Nataša Ružić Public Service Broadcasting in Montenegro Nataša Ružić ANALITIKA Center for Social Research Sarajevo, 2017 Title: Public Service Broadcasting in Montenegro Author: Nataša Ružić Published by: Analitika – Center for Social Research Year: 2017 © Analitika – Center for Social Research, All Rights Reserved Publisher Address: Hamdije Kreševljakovića 50, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH [email protected] www.analitika.ba Proofreading: Gina Landor Copy Editing: Mirela Rožajac-Zulčić Design: Branka Ilić DTP: Jasmin Leventa This publication is produced within the project “The Prospect and Development of Public Service Media: Comparative Study of PSB Development in Western Balkans in Light of EU Integration”, performed together with the University of Fribourg’s Department of Communication and Media Research DCM and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation through the SCOPES (Scientific Cooperation between Eastern Europe and Switzerland) programme. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent opinions of the Swiss National Science Foundation, University of Fribourg and Center for Social Research Analitika. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 6 2. Theoretical AND Methodological Framework 9 2.1. Contemporary Debates on PSB on the Global and EU Level 10 2.2. Key Issues Regarding PBS in Post Communist Countries and the Western Balkans 16 2.3. Methodological Framework 18 3. Country Background 19 3.1. Socio-Political and Economic Context 19 3.2. Media System 21 4. PUBLIC SERVICE Broadcasting IN Montenegro: Research FINDINGS 24 4.1. Background on PSB in Montenegro 24 4.2. Regulation of PSB 28 4.3. -

Midwives' Collaborative Activism in Two U.S. Cities, 1970-1990

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Midwives' Collaborative Activism in Two U.S. Cities, 1970-1990 Linda Tina Maldonado University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Maldonado, Linda Tina, "Midwives' Collaborative Activism in Two U.S. Cities, 1970-1990" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 896. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/896 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/896 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Midwives' Collaborative Activism in Two U.S. Cities, 1970-1990 Abstract ABSTRACT MIDWIVES' COLLABORATIVE ACTIVISM IN TWO U.S. CITIES, 1970-1990 Linda Tina Maldonado Dr. Barbra Mann Wall, PhD, RN, FAAN This dissertation uses historical methodologies to explore the means through which activist midwives in two northeastern cities collaborated, negotiated, and sometimes conflicted with numerous stakeholders in their struggle to reduce infant mortality. Infant mortality within the black community has been a persistent phenomenon in the United States, despite a growing dependence on advancing medical technologies and medical models of birth. Studies in the early twentieth century typically marked poverty as the dominant factor in infant mortality affecting black communities. Refusing to accept poverty as a major determinant of infant mortality within marginalized populations of women, nurse-midwives during the 1970s and 1980s harnessed momentum from the growing women's health movement and sought alternative methods toward change and improvement of infant mortality rates. Utilizing a grassroots type of activism, midwives formed collaborative relationships with social workers, community activists, physicians, public health workers, and the affected communities themselves to assist in the processes of self-empowerment and education. -

3G INTERNET and CONFIDENCE in GOVERNMENT∗ Sergei Guriev R Nikita Melnikov R Ekaterina Zhuravskaya Forthcoming, Quarterly

3G INTERNET AND CONFIDENCE IN GOVERNMENT∗ Sergei Guriev ○r Nikita Melnikov ○r Ekaterina Zhuravskaya Forthcoming, Quarterly Journal of Economics Abstract How does mobile broadband internet affect approval of government? Using Gallup World Poll surveys of 840,537 individuals from 2,232 subnational regions in 116 countries from 2008 to 2017 and the global expansion of 3G mobile networks, we show that, on average, an increase in mobile broadband internet access reduces government approval. This effect is present only when the internet is not censored, and it is stronger when the traditional media are censored. 3G helps expose actual corruption in government: revelations of the Panama Papers and other corruption incidents translate into higher perceptions of corruption in regions covered by 3G networks. Voter disillusionment had electoral implications: In Europe, 3G expansion led to lower vote shares for incumbent parties and higher vote shares for the antiestablishment populist opposition. Vote shares for nonpopulist opposition parties were unaffected by 3G expansion. JEL codes: D72, D73, L86, P16. ∗We thank three anonymous referees and Philippe Aghion, Nicolas Ajzenman, Oriana Bandiera, Timothy Besley, Kirill Borusyak, Filipe Campante, Mathieu Couttenier, Ruben Durante, Jeffry Frieden, Thomas Fuji- wara, Davide Furceri, Irena Grosfeld, Andy Guess, Brian Knight, Ilyana Kuziemko, John Londregan, Marco Manacorda, Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, Chris Papageorgiou, Maria Petrova, Pia Raffler, James Robinson, Sey- hun Orcan Sakalli, Andrei Shleifer, Andrey Simonov, -

The Montenegrin Political Landscape: the End of Political Stability? by Milena Milosevic, Podgorica-Based Journalist Dr

ELIAMEP Briefing Notes 27 /2012 July 2012 The Montenegrin political landscape: The end of political stability? by Milena Milosevic, Podgorica-based journalist Dr. Ioannis Armakolas, “Stavros Costopoulos” Research Fellow, ELIAMEP, Greece The recent start of accession negotiations between the European Commission and Montenegro came against the background of the ever perplexing politics in this Western Balkan country. The minor coalition partner in the ruling government – the Social Democratic Party (SDP) - announced the possibility that it will run in the elections independently from the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), the successor of the Communist Party and the party of former Montenegrin leader Milo Djukanovic. SDP and DPS have been in coalition in the national government continuously since 1998. In contast, opposition parties are traditionally perceived as weak and incapable of convincing voters that they can provide a genuine alternative to DPS-led governments. However, at the beginning of July, news of two opposition parties trying to unite all anti-government forces, with the help of the country’s former foreign minister Miodrag Lekic, once again heated up the debate over the opposition’s strength. At about the same time, news concerning the formation of new parties have also dominated the headlines in the local press. Most of the attention is on “Positive Montenegro“, a newly-formed party whose name essentially illustrates its platform: positive change in the society burdened by past mistakes and divisions. The ambivalent context within which the contours of the current Montenegrin political landscape are being drawn further complicates this puzzle. On one hand, the country’s foreign policy and relations with its neigbours are continuously praised by the international community.