HIGH DESERT VOICES July 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

P2-Dec 00 IJW V6

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness DECEMBER 2000 VOLUME 6, NUMBER 3 FEATURES 31 Wilderness as Teacher 3 EDITORIAL PERSPECTIVES Expanding the College Classroom Wild Rivers and Wilderness BY LAURA M. FREDERICKSON and BAYLOR L. JOHNSON BY DAVID N. COLE 35 The Central and Southern Sierra 4 SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Education Project A Value in Fear An Outreach Program That Works Some Rivers Remembered BY BARB MIRANDA BY LUNA B. LEOPOLD SCIENCE AND RESEARCH STEWARDSHIP 38 PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE 7 The Value of Wilderness to the U.S. Wilderness Monitoring National Wildlife Refuge System New Directions and Opportunities BY JAMIE RAPPAPORT CLARK BY PETER LANDRES 12 Managing Campsite Impacts 39 Autonomous Agents in the Park on Wild Rivers An Introduction to the Grand Canyon Are There Lessons for Wilderness Managers? River Trip Simulation Model BY TERRY C. DANIEL and H. RANDY GIMBLETT BY DAVID N. COLE 17 The San Marcos River Wetlands Project WILDERNESS DIGEST Restoration and 44 Announcements & Wilderness Calendar Environmental Education in Texas BY THOMAS L. ARSUFFI, PAULA S. WILLIAMSON, 47 Book Reviews MARTA DE LA GARZA-NEWKIRK, and MELANI HOWARD • The Wilderness Concept and the Three Sisters Wilderness Voyage of Recovery by Les Joslin 22 REVIEWED BY JOHN HENDEE Restoration of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River • Requiem for Nature BY ANNIE STRICKLER by John Terborgh REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION • The River Reader Edited by John A. Murray 27 A Community-Based Wilderness REVIEWED BY CHRIS BARNS Education Partnership in Central Oregon Front cover photo of the headwaters of the Blackfoot River, Montana, USA © 2000 by the Aldo Leopold Institute. -

A History of the Arôhitecture Of

United States Department of Agriculture A History of the I Forest Service Engineering Staff EM-731 0-8 Arôhitecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service a EM-731 0-8 C United States Department of Agriculture A History of the Forest Service EngIneering Staff EM-731 0-8 Architecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service by John A. Grosvenor, Architect Pacific Southwest Region Dedication and Acknowledgements This book is dedicated to all of those architects andbuilding designers who have provided the leadership and design expertise tothe USDA Forest Service building program from the inception of theagencyto Harry Kevich, my mentor and friend whoguided my career in the Forest Service, and especially to W. Ellis Groben, who provided the onlyprofessional architec- tural leadership from Washington. DC. I salute thearchaeologists, histori- ans, and historic preservation teamswho are active in preserving the architectural heritage of this unique organization. A special tribute goes to my wife, Caro, whohas supported all of my activi- ties these past 38 years in our marriage and in my careerwith the Forest Service. In the time it has taken me to compile this document, scoresof people throughout the Forest Service have provided information,photos, and drawings; told their stories; assisted In editing my writingattempts; and expressed support for this enormous effort. Active andretired architects from all the Forest Service Regions as well as severalof the research sta- tions have provided specific informationregarding their history. These individuals are too numerous to mention by namehere, but can be found throughout the document. I do want to mention the personwho is most responsible for my undertaking this task: Linda Lux,the Regional Historian in Region 5, who urged me to put somethingdown in writing before I retired. -

Annotated Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Many of the sources described below are available in the Region 4 History Collection, Ogden, Utah. Alderson, William T and Shirley Payne Low. Interpretation of Historic Sites. Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History, 1976. This book is a short exploration of how to develop and run programs at historic sites. It is directed towards administrators, developers and prospective historic interpreters. Alderson was Director of the American Association for State and Local History and Low was Supervisor of Hostess Training at Colonial Williamsburg. Their book includes information on preserving historic structures and sites, as well as preparing security measures and planning presentation methods for audiences and interpreters. It references several historical sites across the country and features black and white photographs, a brief index, and a suggested reading list. It should be noted presentation tools described for this publication may be out of date. Alexander, Thomas G. A Clash of Interests: Interior Department and Mountain West 1863-96. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1977. Alexander, the Associate Director of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at BYU, provides an in-depth study of the Interior Department’s relations with the Intermountain West—specifically the Idaho, Utah, and Arizona Territories spanning 1863 to 1896. Topics include Territorial Policy of the time-period, Native American consolidation and acculturation, and frontier commonwealth policies. The book includes maps, tables, and a bibliographic essay of further reading. This is a useful source for anyone interested in the history of the Mountain West, the development of land policy in the territories, or the interactions between the federal government and Native American peoples. -

HIGH DESERT VOICES July 2015

HIGH DESERT VOICES July 2015 News and Information published by and for Volunteers Glow: Living Lights Exhibit by Siobhan Sullivan, Newsletter Editor As you step into the new Glow: Living Lights exhibit, your eyes quick- ly adjust to the darkened room and the kiosks full of information related to bioluminescence. The word bioluminescence is derived from the Greek bios ‘living’ and lumine ‘light’. Though many land species are biolumi- nescent, 90% of life in the sea has the ability to glow. Several land-dwelling bioluminescent plants and animals are high- lighted. There is a small model of a luminous land snail with its yellow- green light. The South American railroad worm is unique in that it glows in more than one color. The body segments put off a yellow-green light and the head has two red lights that resemble headlights. A live Emperor scorpion, a species from West Afri- ca, is featured in this part of the display. Forty species of mushrooms have the characteristic of glowing. In the High Desert the world’s largest living fungus, Armillaria solidipes, AKA the Humong- ous Fungus, glows. The specimen in Malheur National Forest covers an area of 3.4 square miles and is thought to be 2,400 years old. The bioluminescence of fungi may serve to attract insects that will spread their spore or serve as a defense mechanism to keep potential predators away. Fireflies communicate by flashing their lights. A male firefly will flash its yellow light every six seconds while trying to attract a mate. If a female flashes within two seconds of his flashing, she is more likely to attract a male. -

January Edition

The Lookout Newsletter of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees “Sustaining the Heritage” January 2016 Happy New Year! NAFSR Presents John R. McGuire Awards to RMS Researcher and to Malheur This week NAFSR and the Public Lands Foundation sent a letter to United States National Forest Leaders Attorney General Lynch regarding the takeover of the Wildlife Refuge in Harney County Oregon, imploring the Justice Department to take action against “those who are making a mockery of U.S. law.” If you have not yet seen that letter, you may find it by Clicking Here. NAFSR presented two John R. McGuire Awards this fall and we lead with the details of those events. It has always been the favorite of all my “presidential” duties to present these awards. Know that there are lots of great employees doing good things out there! Former Chief Jack Ward Thomas has just released a trilogy of his experiences. We include some information and contacts. Les Joslin is a frequent contributor and sends us a short piece about a former First Lady and her memorable experience with the Forest Service in Oregon. And here is a link to a video that an excellent primer on the Wildfire Disaster Funding Act. It includes some great talking points. It is only 1.5 minutes long and is worth your time. Pass it along to your friends and your members of Congress! Clic k Here! Finally I wish you all the best in the coming year! NAFSR will be on duty staying Top: Chief Tidwell, NAFSR Chair Jim Golden and recipient Dr. -

High Desert Museum Access Programs Made Possible in 2021 by Mid Oregon Credit Union

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, February 12, 2021 Contact: Heidi Hagemeier, director of communications, 541-382-4754 ext. 166, [email protected] High Desert Museum Access Programs Made Possible in 2021 by Mid Oregon Credit Union BEND, OR — The High Desert Museum is proud to announce that Mid Oregon Credit Union is serving as the Museum’s 2021 Access Initiatives Sponsor. The Museum offers a variety of free and reduced-admission options to ensure our educational experiences are accessible to all. A new access program made possible by Mid Oregon Credit Union is Wonder Wednesdays, which began in early December. In an effort to provide engaging activities for students, parents and/or caregivers visiting the Museum on Wednesdays with pre-kindergarten to 12th grade children who attend school in Deschutes, Jefferson, Crook, Lake and Klamath counties receive a reduced admission price of $5 per person. Learn more at highdesertmuseum.org/wonder-wednesdays. “We’re very grateful to our generous partners at Mid Oregon Credit Union,” says Museum Executive Director Dana Whitelaw, Ph.D. “Their support is critical to the Museum’s goal that visitors from every walk of life can experience our exhibitions, wildlife and history.” “The High Desert Museum is a priceless resource for our Central Oregon community,” comments Kyle Frick, Vice President of Marketing and Community Relations for Mid Oregon Credit Union. “Mid Oregon Credit Union values our decades-long relationship with the Museum and the opportunity to work together on programs that have impacted tens of thousands of individuals and families. We appreciate the Museum continuing to provide educational and cultural resource access through these challenging times!” Museum and Me is another popular Museum access program. -

Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees — Fall 2012 President’S Message—Mike Ash

OldSmokeys Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees — Fall 2012 President’s Message—Mike Ash I’m writing this message amidst the arrival of the fall colors in beautiful Vail, Colorado, following a fantastic U.S. Forest Service retiree reunion called “Rendezvous in the Rockies.” This reunion was well attended by over 650 members of our retiree family, in- cluding over a hundred OldSmokeys! It was great to see so many good friends, many of whom were anxious to check in on those of you who were not able to attend. I am so proud to be a part of our great Forest Service family. I honestly cannot think of another organization in the world whose members maintain such a great relationship as we do. Speaking of our Forest Service family, I want to point out that the OldSmokeys of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Association (PNWFSA) are the largest and probably most active of all the Forest Service retiree organizations. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fine cadre of men and women who keep our PNWFSA going. This cadre includes the Board of Directors, the various committee members, those of you who step up and take on the responsibility to coordinate an event or publish a book or write an article for the newsletter, or any of the other logistical items it takes to keep things working for our organization of 920+ members. Sometimes I cringe a bit when I think that it might be time to give some of these workhorses a break even as I worry that their work might be missed. -

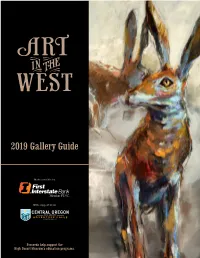

2019 Gallery Guide

2019 Gallery Guide Made possible by Member FDIC. With support from Proceeds help support the High Desert Museum’s education programs. The High Desert Museum is pleased to present Art in the West, our annual art exhibition and silent auction. This juried, invitation-only national exhibition showcases the inventive and varied ways in which artists respond to the people, landscapes, history and wildlife of the High Desert. The artwork gives Museum visitors the opportunity to view the rugged splendor and unique stories of the West through the eyes of its most creative residents. The artwork featured in Art in the West is available for sale by silent auction. Bids can be placed at the Museum’s store, Silver Sage Trading, or by phone at 541-382-4754 ext. 365 through Saturday, August 24 at 2:00 pm. Final bidding will occur during the High Desert Rendezvous auction that evening. Artwork can also be purchased outright. Proceeds from the auction help support the Museum’s education programs. Your purchase not only allows you to own original artwork by regionally and nationally acclaimed artists, but it also enables the Museum to bring quality science, art and history education to lifelong learners throughout the region. Cover: Wus Up?, Dawn Emerson1 Nikolo Balkanski Awaiting, 2018 Oil 18.5” x 22.5” Nikolo Balkanski moved from Finland to Colorado in 1986. It was then that he began devoting more time to painting the Western landscape, although he continues to paint portraits, still lifes and figurative works. Over the years, Nikolo has been involved in countless solo and group exhibitions including Artists of America, Great American Artists, Artists of the West, American Impressionists Society, Inc., Oil Painters of America, The Brinton Museum, the Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale, The Russell Exhibition and Sale, Western Visions Show and Sale and others. -

HIGH DESERT VOICES August 2015

HIGH DESERT VOICES August 2015 News and Information published by and for Volunteers Burro or Donkey? by Lynne Schaefer, Newsletter Writer With the addition of two companions for Sage and Izzy the mustangs, a question overheard fre- quently at the Miller barn and corral is, “What is the difference between a donkey and a burro?” It all depends on whom you ask. The dictionary defines a burro as a small donkey used as a pack animal in the southwestern United States and Mexico; a donkey, Equus asinus, is an ass; an ass is a long-eared, sure-footed, domesticated mammal related to the horse and used as a beast of burden. “Burro” is Spanish for an ass. “Burro” is also used to describe feral donkeys. That is the an- swer Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) Rob Sharp gave at Mustang Awareness Day last Septem- ber: “A burro is a wild donkey.” The first donkeys arrived with the second voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1495, multiplied in Mexi- co, and crossed the Rio Grande to the United States around 1598. They aided natives at mission settlements to grind flour and gold prospectors as pack animals. Most were then abandoned and established the feral popula- tion with mustangs. A mule is a cross between a male horse (stallion) and a female donkey (jenny), or a male donkey (jackass) and a female horse (mare). Mules cannot reproduce. A mule is larger and stronger than a donkey but more sure-footed than a horse. Burros come in a variety of colors but The High Desert Museum’s two burros from the BLM display two different variations. -

<Abstract Centered> an ABSTRACT of the THESIS OF

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Chaylon D. Shuffield for the degree of Master of Science in Forest Resources presented on December 21, 2010. Title: Overstory Composition and Stand Structure Shifts within Inter-mixed Ponderosa Pine and Lodgepole Pine Stands of the South-central Oregon Pumice Zone. Abstract approved: _____________________________________________________________________ John D. Bailey Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta var. murrayana) forests of south-central Oregon have been extensively researched over the last century. However, little information has been reported on overstory composition and stand structure shifts associated with fire exclusion within inter-mixed ponderosa pine and lodgepole pine stands of the south-central Oregon pumice zone. In recent time, the lack of disturbance history and quantitative information needed to reconstruct historic stand conditions has become a growing concern for many ecologists. The need to collect quantitative information from remnant old-growth stands is imperative to improve restoration activities, incorporate stand-level diversity, identify the degree of successional departure, and to ensure valuable data is archived for future reference and ecological analysis. In Chapter 1, an exhaustive search for published information on early land-use practices specific to our study area was performed to: (1) identify the degree of Native American influence on vegetation; (2) identify direct and indirect Euro-American disturbances involving the loss of natural processes; and (3) establish a reference period for appropriate representation of historic conditions. In Chapter 2, remnant old-growth stands were analyzed using dendrochronological techniques and statistical comparisons to quantify: (1) shifts in overstory composition and stand structure; (2) growth and development of ponderosa pine and lodgepole pine across time; and to (3) characterize the influence of climate and fire on species recruitment. -

Position Description

Position Description Title: Associate Curator of Wildlife Division: Wildlife Classification: Full time Reports To: Curator of Wildlife Supervises: Seasonal wildlife specialists, interns and volunteers Starting Wage: $39,000 annually High Desert Museum – Organization Description Since opening in 1982, THE HIGH DESERT MUSEUM has brought together wildlife, culture, art and natural resources to promote an understanding of the natural and cultural heritage of North America's High Desert country. We do so through indoor and outdoor exhibits, wildlife in natural habitats, living history demonstrations and dynamic programs on a beautiful, 135-acre campus in the pine forest. The Museum is a nonprofit organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, was a 2018 National Medal for Museum and Library Sciences finalist and is a Smithsonian Affiliate. During the 2018-19 fiscal year, 195,000 visitors enjoyed the Museum. The Museum is located in Bend, Oregon, a fast-growing, charismatic city nestled against the Cascade Range at the edge of the High Desert. We strive to be inclusive, culturally humble, relevant, curious and mindful. As a team, we work together to wildly excite and responsibly teach, creating connection to and dialogue about the High Desert. Job Summary – Associate Curator of Wildlife We are seeking a dynamic individual to provide programs and exhibit support as part of the Wildlife Team at the High Desert Museum. The Associate Curator is responsible for the safety, well-being and exhibition of assigned animals. Experience with wildlife husbandry, training and handling is essential. The Associate Curator of Wildlife conducts public programs with and without live animals, and must have excellent interpersonal, presentation and written skills.