Why Do We Compact Soil ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertise in Ohio Asphalt

The Journal of Ohio’s Asphalt Professionals Summer 2017 Issue 2 • V o l u m e 1 4 FPO'S COOLEST EXP ! OHIO RIDES ON US OPERATOR COMFORT & CONVENIENCE MAKE THE JOB EASIER EACH ROADTEC PAVER IS ERGONOMICALLY DESIGNED FOR BETTER VISIBILITY, REDUCED NOISE, AND COMFORT. The New Clearview FXS® fume extraction system provides greater visibility to the front of the paver hopper, to the opposite side, and down to the augers. Paver controls are mounted to the pivoting seat station, which hydraulically swings out past the side of the machine for excellent visibility. All functions are easily accessible, including feed system and flow gate controls. Noise levels cut in half and improved visibility allow the operator to stay in constant communication with the rest of their crew. LET ROADTEC MAKE YOUR JOB EASIER - VISIT ROADTEC.COM © 2015 ROADTEC. INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1.800.272.7100 +1.423.265.0600 Untitled-2 1 8/19/15 1:32 PM www.columbusequipment.com Ohio’s Dependable Dealer Columbus Equipment Company and Roadtec Partner to Optimize Uptime and Production Through “ Industry-Leading Support of Innovative, High-Quality, Dependable Road Building and Asphalt Paving Equipment. The biggest benefit of Roadtec equipment is uptime. We just don’t have the downtime we have had with other machines. “ Dean Breese; Vice President, Gerken Paving Inc. Serving You From Ten Statewide Locations COLUMBUS TOLEDO CINCINNATI RICHFIELD CADIZ (614) 443-6541 (419) 872-7101 (513) 771-3922 (330) 659-6681 (740) 942-8871 DAYTON MASSILLON ZANESVILLE PAINESVILLE PIKETON (937) 879-3154 (330) 833-2420 (740) 455-4036 (440) 352-0452 (740) 289-3757 www.columbusequipment.com Officers Chairman Cole Graham Shelly and Sands, Inc. -

Revised Plans for Conditions 3,4 and 5

Car Parking 1:200 WILKINSON WAY 9 10 12 KEEP CLEAR New crossing points to be 1,200 formed including dropped 800 kerbs and blister type tactile paving. Existing tarmac paving made good as 19 necessary. Existing Yellow Zigzag line & 800 School wording to this side of KEEP CLEAR the Road overall length from 1,200 School gate around into Chapel Close = 52m. 18 20 Refer to Photograph below. 17 Existing Yellow Zigzag line & 21 1 School wording to this side of the Road overall length from School gate around into Foster Close = 45m. Refer to Photograph below. 12no. existing car parking 22 space to be retained. Spaces to receive new thermoplastic white lining Planting area to end of revised central island c/w 14no. new car parking new tree to replace existing spaces to be created to central island area delineated with new thermoplastic white lining 3 New thermoplastic white lining indicating one-way FOSTER CLOSE flow of traffic, (clockwise) New HB2 type kerbs to be provided to form planter area Line of 10No. existing car parking spaces within central island to be removed and layout amended thus 4 Planting area to end of 2no. limited time parking revised central island c/w spaces to be allowed for new tree to replace existing pick up/drop off etc. Existing Disabled Parking provision retained with 2no. oversize bays c/w pole Existing block paving New HB2 type kerbs to mounted signage and surface, where broken out, be provided to form thermoplastic white to be replaced with new planter area 15 disabled symbol to centre of tarmacadam highway bay construction to match existing build up adjacent 14 16 New thermoplastic white lining indicating one-way flow of traffic, (clockwise) 5 12 View towards School Entrance from Wilkinson Way 3No. -

Triflex Preco Line 300

Product overview Marking system Triflex Preco Line 300 Triflex Preco Line 300 is a thin layer cold spray or roller applied, fast curing, marking system which offers a number of benefits when compared to traditional chlorinated rubber based solutions. The simple to apply 1 component solution is fully compatible with a wide range of substrates including direct application to asphalt and concrete and can be applied to many existing marking materials. The system is used extensively on car parks and roads and is widely used on airports due to its thin layer application. System highlights Application areas Toluene and xylene free Triflex Preco Line 300 is a toluene and xylene free solution, making it more Car park markings environmentally friendly and safer to apply than many other spray applied Road markings marking products, including the majority of chlorinated rubber markings. Industrial floor markings Warehouse markings Maximum colour and design possibilities Create a design to meet your safety and aesthetic requirements with a wide Compatible substrates range of standard colours and options for bespoke colours - refer to Triflex Preco Line 300 Colour card. The colour range is significantly wider than the traditional white and yellow offered by other materials. • Asphalt including Hot Rolled Asphalt (HRA) and Stone Mastic Asphalt Versatility and compatibility (SMA) Triflex Preco Line 300 is fully compatible with a wide range of substrates and • Tarmac / Tarmacadam / Macadam often requires no primer. • Fresh asphalt including HRA and SRA • Fresh Tarmac / Tarmacadam / Macadam Totally cold applied • Concrete There is no risk from hot works during installation as all Triflex materials are • Existing markings applied in a totally cold liquid form, curing to create a tough, durable solution • Pavers / brick paviours that lasts. -

Transportation and Road Pavements the Neighbourhood Planning and Design Guide

Section I Transportation and road pavements The Neighbourhood Planning and Design Guide Part II Planning and design guidelines Symbols at text boxes More detailed information is provided about the issue under discussion Important considerations to be aware of are highlighted Relevant content from a complementing resource is presented PART I: SETTING THE SCENE A The human settlements context B A vision for human settlements C Purpose, nature and scope of this Guide D How to use this Guide E Working together PART II: PLANNING AND DESIGN GUIDELINES F Neighbourhood layout and structure G Public open space H Housing and social facilities I Transportation and road pavements J Water supply K Sanitation L Stormwater M Solid waste management N Electrical energy O Cross-cutting issues Planning and designing safe communities Universal design Developed by Department of Human Settlements Published by the South African Government ISBN: 978-0-6399283-2-6 © 2019 Version 1. Printed January 2019 Section I Transportation and road pavements The Neighbourhood Planning and Design Guide The Neighbourhood Planning and Design Guide I Transportation and road pavements Table of contents I.1 Outline of this section ............................................................................................................................. 4 I.1.1 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 I.1.2 Content and structure ............................................................................................................................... -

Highway Engineering

HIGHWAY ENGINEERING HIGHWAY ENGINEERING Martin Rogers Department of Civil and Structural Engineering Dublin Institute of Technology Ireland Blackwell Science To Margaret, for all her love, support and encouragement © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd First published 2003 Editorial Offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ A catalogue record for this title is available from the Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 British Library 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK Tel: +44 (0)1865 791100 ISBN 0-632-05993-1 Blackwell Publishing USA, 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5018, USA Library of Congress Tel: +1 781 388 8250 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Iowa State Press, a Blackwell Publishing Rogers, Martin. Company, 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa Highway engineering / Martin Rogers. – 1st ed. 50014-8300, USA p. cm. Tel: +1 515 292 0140 ISBN 0-632-05993-1 (Paperback : alk. paper) Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allé, 1. Highway engineering. I. Title. P. O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, TE145.R65 2003 Denmark 625.7 – dc21 Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 2003005910 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Set in 10 on 13 pt Times Victoria 3053, Australia by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Blackwell Verlag, Kurfürstendamm 57, TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall 10707 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 (0)30 32 79 060 Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir For further information on Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 www.blackwellpublishing.com The right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Walking & Cycling Technical Design Guidance 2016 a Quick

Walking & Cycling Technical Design Guidance 2016 A quick reference guide to supplement The Royal Parks Walking and Cycling Technical Design Guidance first published in 2016. The main guidance document should be referred to for detailed design advice. This document summarises our recommended approach and tools for planning and designing walking and cycling related infrastructure in busy parkland settings. 2 INTRODUCTION The Royal Parks THE ROYAL PARKS Experience and Challenges 3 The Royal Parks recognise that historic WHY DO WE NEED WALKING CYCLING A DESIGN GUIDE? Over 90% of the 80 million visits to the Infrastructure improvements that are sensitive landscapes and multifunctional parks are The Royal Parks Walking and Cycling Technical Royal Parks are enjoyed on foot and this to the parkland setting can be an effective way important in people’s lives for many varied Design Guidance (2016) was produced after has significantly increased over the past few to enhance the experience and enjoyment of more than 10 years of research and observation, years. Walking activities within the parks the parks for all visitors. The design guide sets reasons, attracting millions of visitors each year. monitoring the changing relationship of walking are undertaken for a multitude of reasons; out how to ensure that a scheme proposal In addition to Richmond Park, Greenwich Park, and cycling in London’s Royal Parks. Existing as an important part of people’s health and is fit for purpose and appropriate for the Hyde Park, St James’s Park, the Green Park, urban design best practice for walking and wellbeing, as well as providing for national and context. -

Effect of Pavement Conditions on Rolling Resistance

American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 2014 American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) e-ISSN : 2320-0847 p-ISSN : 2320-0936 Volume-3, Issue-7, pp-141-148 www.ajer.org Research Open Access Effect of Pavement Conditions on Rolling Resistance Mr.Dipanjan Mukherjee M.Tech CIVIL ENGINEERING (Pursuing),NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Silchar,Assam,INDIA; B.Tech West Bengal University of Technology, West Bengal,INDIA, ABSTRACT: Rolling resistance is the force acting on a vehicle over a full journey. It is generated by the hysteresis of tyre and pavement. Rolling resistance, sometimes called rolling friction or rolling drag, is the force resisting the motion when a body (such as a ball, tire, or wheel) rolls on a surface. It is mainly caused by non-elastic effects; that is, not all the energy needed for deformation (or movement) of the wheel, roadbed, etc. is recovered when the pressure is removed. A hysteresis phenomenon can be observed when viscoelastic materials undergo a load-then-unload process. A typical hysteresis curve of viscoelastic material can be found. The shadow area enclosed by the hysteresis loop represents energy loss. A characteristic of a deformable material such that the energy of deformation is greater than the energy of recovery. The rubber compound in a tire exhibits hysteresis. As the tire rotates under the weight of the vehicle, it experiences repeated cycles of deformation and recovery, and it dissipates the hysteresis energy loss as heat. Hysteresis is the main cause of energy loss associated with rolling resistance and is attributed to the viscoelastic characteristics of the rubber. -

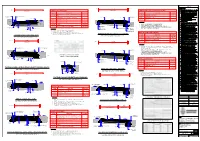

Tarmacadam Footway/Cycleway Tarmacadam Carriageway Reported to the Highway Authority/Engineer

NOTES PRIVATE FOOTWAY EXTENT CARRIAGEWAY CARRIAGEWAY LAND EXTENT FOOTWAY SEE NOTE 23 ABOUT WIDTH SEE NOTE 21 ABOUT WIDTH TARMACADAM CARRIAGEWAY TARMACADAM (FLEXIBLE) FOOTWAY/CYCLEWAY COURSE SPECIFICATION THICKNESS COURSE SPECIFICATION THICKNESS HOT ROLLED ASPHALT. 30/14F + PCC 14/20, PEN 40/60, MIN PSV 63, MAX SURFACE 40 SURFACE CLOSE GRADED AC6, PEN 100/150. 25 AAV 14. KERB HAUNCHING/BEDDING UPSTAND BETWEEN C/WAY SURFACE UPSTAND BETWEEN C/WAY AS PER WDS_HD_03, 'VARIED AND TOP OF BULLNOSE KERB RADII TO SURFACE AND TOP OF BULLNOSE UPSTAND KERBS' BE 125 CLOSE GRADED AC10, PEN 100/150, MIN PSV 60, MAX AAV 14 40 BINDER COURSE SURFACE COURSE KERB RADII TO BE 125 BINDER CLOSE GRADED AC20, PEN 40/60. 75 SURFACE COURSE 1:40-1:60 GRADIENT SEE TABLE 1:40 GRADIENT 1:40 GRADIENT BINDER CLOSE GRADED AC20, PEN 40/60. 60 SUB-BASE DfT TYPE 1 NOTE 2 FOOTWAY CONSTRUCTION BASE CLOSE GRADED AC32, PEN 40/60. 130 TABLE NOTES CARRIAGEWAY SEE TABLE C/WAY CONSTRUCTION SUB-BASE DfT TYPE 1 CONSTRUCTION 1. SEE NOTE 9 FOR DETAILS ON BOND COATS BETWEEN LAYERS; NOTE 3 2. SUB-BASE REQUIREMENTS TO BE DETERMINED BY CBR TEST; SEE TABLE EDGING KERB DETAIL AS 3. CARRIAGEWAY CAPPING REQUIREMENTS TO BE DETERMINED BY CBR TEST; CAPPING CLASS 6F1 OR 6F2 GRANULAR CAPPING MATERIAL PER WDS_HD_03, BULLNOSE KERB DETAIL. NOTE 4 'STRAIGHT KERBS' 4. CBR TEST TO BE CARRIED OUT BY THE CONTRACTOR AT 20-30m INTERVALS AND RESULTS SEE WDS_HD_02 BINDER COURSE SUB-BASE 'STRAIGHT KERBS' REPORTED TO THE HIGHWAY AUTHORITY/ENGINEER. -

A20 Coldharbour Roundabout

A20 Coldharbour Roundabout Segregated Left Turn Lane Option Study January 2015 Maidstone Borough Council A20 Coldharbour Roundabout 344395HH01 HWY HDS 001 A A20 Coldharbour Roundabout - Segregated Left Turn Lane January 2015 Segregated Left Turn Lane A20 Coldharbour Roundabout Option Study Segregated Left Turn LaneOption Study January 2015 Maidstone Borough Council Maidstone House King Street Maidstone Kent ME15 6JQ Mott MacDonald, Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 8774 2000 F +44 (0)20 8681 5706 W www.mottmac.com A20 Coldharbour Roundabout Segregated Left Turn LaneOption Study Contents Chapter Title Page Executive Summary i 1 Introduction 1 1.1.1 Location plan ______________________________________________________________________ 2 1.2 Design reference documents __________________________________________________________ 4 1.3 Site visit __________________________________________________________________________ 4 1.4 Accident data ______________________________________________________________________ 5 2 Design considerations applicable to both options 6 2.1 Extending an existing traffic deflection island and increasing areas of hatching ___________________ 6 2.2 Lane designations on approach to the segregated left turn lane _______________________________ 6 2.3 Swept path analyses ________________________________________________________________ 7 2.4 Compliance with the Design Manual for Roads and Bridges __________________________________ 7 2.4.1 Carriageway width __________________________________________________________________ -

An Introduction to Asphalt Paving

An Introduction to Asphalt Paving: History: Naturally occurring petroleum asphalt dates back to around 4000 B.C.. Early uses include: caulking for boats, cement for jewelry, sealing of bathing pools/water tanks, embalming of mummies, coloring material in paintings, lamp illumination, and as an incendiary device for warfare. The first recorded use of asphalt as a road-building material was in Babylon between 625-650 B.C. Modern applications started in the 1860’s in Scotland where builders began using hot coal tar to bond stones together on roadways reducing dust and maintenance. These roads became named after a John Loudon McAdam tarmacadam, later shortened to tarmac. The first significant paving project in North America was Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. which was completed in 1876. By the turn of the century tarmac was being laid in major centers around the world. Materials: Paving asphalt is a mix of petroleum asphalt (commonly referred to as bitumen), aggregate and additives that is very commonly used as a top layer of pavement for roads. Typical paving asphalt is comprised of 90-95% aggregate and 5-10% bitumen. Paving asphalt is also sometimes referred to as asphaltic concrete or tarmac. There are many types of paving asphalt that are used for a variety of applications. The factors that change an asphalt mix design are oil and aggregate. An aggregate with a larger average size of rock and less sand will provide greater strength, whereas one with smaller rocks and a higher sand content will look nicer, but with less strength. Stronger mixes are used as road base and on highways, and sandier aesthetic mixes are used to resurface parking lots and roadways. -

Pavement Rehabilitation Factsheet

Pavement Rehabilitation Water Quality Factsheet for Permit Applicants Mike Sandecki, Water Quality Program California Coastal Commission This factsheet is a summary of information compiled by Water Quality Program staff. It is not a requirement by the Coastal Commission, and it may be superseded by site-specific information. Introduction This factsheet focuses on the water quality impacts of pavement rehabilitation. Water quality issues for pavement rehabilitation projects may be of concern both during the grinding process used to remove the old pavement, as well as during the construction of new pavement or application of sealants. Pavement Materials The two most common types of pavement can be distinguished by their color. Portland Cement Concrete – commonly called concrete – is a light-colored pavement (labeled PCC on plans and project specification documents) that uses Portland cement as a binder to harden, waterproof, and texture the pavement. Portland cement is made from calcium carbonate (i.e., limestone) derived from marine fossils. Asphalt Concrete – commonly called blacktop or asphalt – is a dark-colored pavement (labeled AC on plans and project specification documents) that uses asphaltic cement as a binder. Asphaltic cement (also called bitumen) is produced from a complex blend of hydrocarbons and organic compounds that is derived from petroleum byproducts. PCC and AC pavements consist of multiple layers, including a compacted foundation, a base material layer, and a driving surface. A surface sealant may also be applied to protect the pavement. The bulk of both PCC and AC pavements is comprised of mineral aggregate. Mineral aggregate is a blend of rock of various sizes and shapes, derived either from sand and gravel mined from alluvial deposits, or from crushed stone quarried from bedrock sources. -

Part 2 - Wood, Asphalt, and Other Surfaces by Don Clow

FROM MACADAM TO ASPHALT 3 FROM MACADAM TO ASPHALT - THE PAVING OF THE STREETS OF LONDON IN THE VICTORIAN ERA Part 2 - Wood, Asphalt, and other surfaces by Don Clow INTRODUCTION Part I of this article dealt primarily with unbound macadam, tar-bound macadam, and granite sett surjaces, this part deals with the introduction of wood, asphalt and a variety of other paving Qpes in the Metropolis. WOOD BLOCKS Russia appears to have been the first to use wood blocks for paving. The first use in London was in Offord Street in 1838. A painting by Scharf shows the blocks (apparently square) bging laid. A tar boiler also appears in the painting and a workman is shown pouring hot lar (or pitch) as a grout between the blocks. The City of London followed in 1839 when wood blocks were laid in Old Bailey. These were of Carey's Patent System with interlocking hexagonal blocks measuring from 6 to 8 inches across, and 4 to 6 inches deep. This surface soon failed, said to be caused by the lack of a proper foundation. This installation was followed by in1\'Iincing L_ane in 1841, and Gracechurch Streetin 1842, again using Carey's blocks and bedded in gravel. This time the blocks were larger , 6 1r2 to J rb rnches across, 13 to 15 inches wide, and 8 or 9 inches deep. Oxford Street was reported to have been paved largely with wood by 1844. In 1849, Haywood reported on trials with three different types but concluded that wood paving ry?q a faiiure.