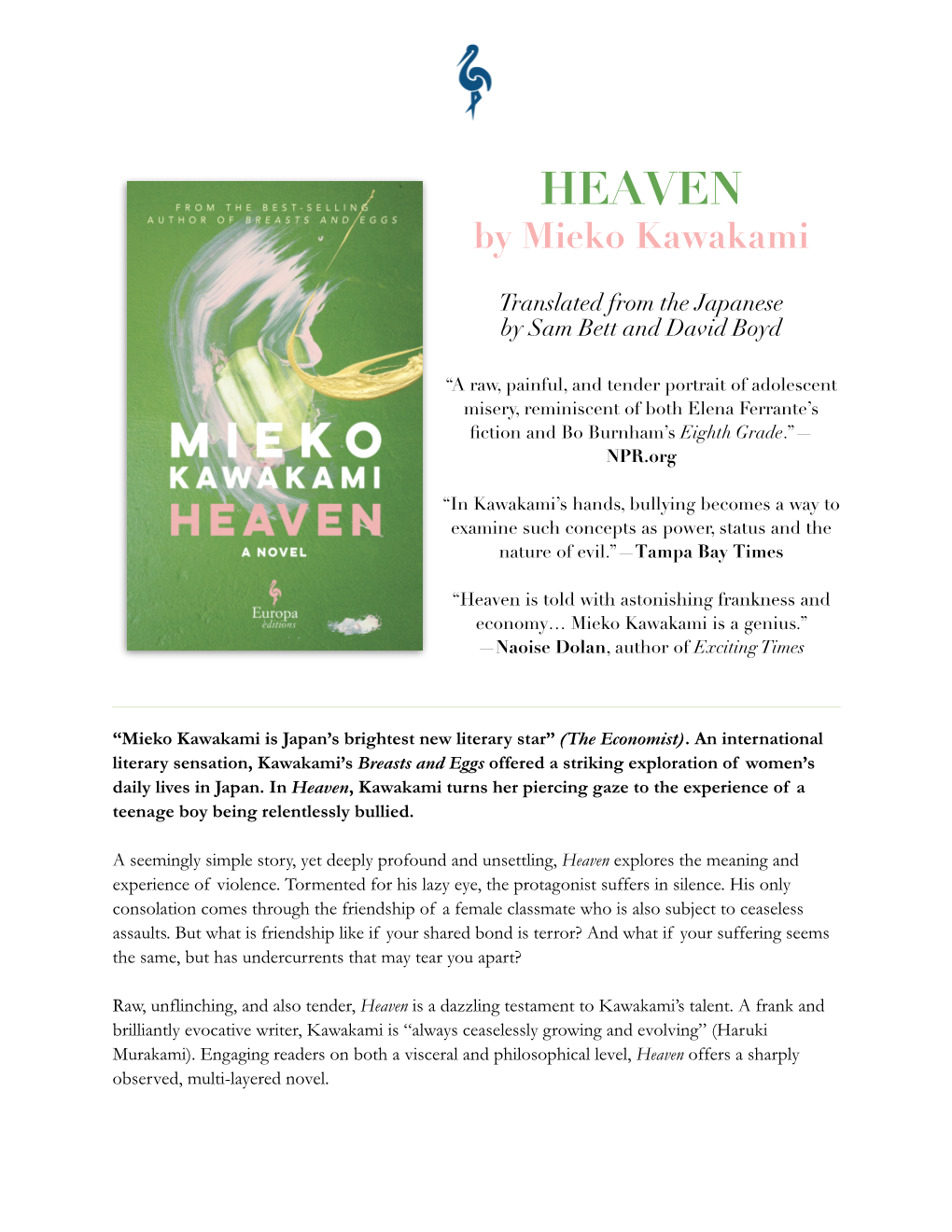

HEAVEN by Mieko Kawakami Translated From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melodrama Or Metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels

This is a repository copy of Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126344/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Santovetti, O (2018) Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. Modern Language Review, 113 (3). pp. 527-545. ISSN 0026-7937 https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.113.3.0527 (c) 2018 Modern Humanities Research Association. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Modern Language Review. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels Abstract The fusion of high and low art which characterises Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels is one of the reasons for her global success. This article goes beyond this formulation to explore the sources of Ferrante's narrative: the 'low' sources are considered in the light of Peter Brooks' definition of the melodramatic mode; the 'high' component is identified in the self-reflexive, metafictional strategies of the antinovel tradition. -

Faith Fox Jane Gardam

cat fall 17 OK M_Layout 1 14/02/17 15:46 Pagina 1 Europa editions September 2017-January 2018 Europa editions www.europaeditions.com cat fall 17 OK M_Layout 1 14/02/17 15:29 Pagina 2 #FERRANTEFEVER – THE NEAPOLITAN QUARTET “Nothing quite like it has ever been published . Brilliant novels, exquisitely translated.” —Meghan O’Rourke, The Guardian “One of modern fiction’s richest portraits of a friendship.” —John Powers, NPR’s Fresh Air Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781609450786 • ebook: 9781609458638 “The Neapolitan novels tell a single story with the possessive force of an origin myth.” —Megan O’Grady, Vogue Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781609451349 • ebook: 9781609451479 “Elena Ferrante is one of the great novelists of our time . This is a new version of the way we live now—one we need, one told brilliantly, by a woman.” —Roxana Robinson, The New York Times Book Review Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781609452339 • ebook: 9781609452230 “The first work worthy of the Nobel prize to have come out of Italy for many decades.” —The Guardian Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781609452865 • ebook: 9781609452964 2 cat fall 17 OK M_Layout 1 14/02/17 15:29 Pagina 3 #FERRANTEFEVER “An unconditional masterpiece.” —Jhumpa Lahiri, author of The Lowland Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781933372006 ebook: 9781609450298 “The raging, torrential voice of the author is something rare.” —Janet Maslin,The New York Times Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781933372167 ebook: 9781609451011 “Stunningly candid, direct and unforgettable.” —Publishers Weekly Available Now • Fiction • Paperback • 9781933372426 ebook: 9781609451035 “Wondrous . another lovely and brutal glimpse w of female subtext, of the complicated bonds between mothers and daughters.”—The New York Times Available now • Picture Book • Hardcover • 9781609453701 ebook: 9781609453718 me “The depth of perception Ms. -

Risa Wataya (Kioto, 1984) Con Alguien Mucho Más Mar- Escribió a Los 17 Años Su Pri

Te daría un puñetazo relata el día a día de la joven Hatsumi en su primer año de institu- to, una auténtica pesadilla cuyos elementos recurren- tes son su incapacidad para encajar con otros seres humanos y el abandono pro- gresivo de la única amiga que Quiero que me acepten. Quiero que me reconozcan. creía tener. Todo cambia (a peor) cuando, debido a un Quiero que alguien saque de mi corazón todas esas proyecto de ciencias, acaba cosas negras, como si quitara horquillas del pelo, y Risa Wataya (Kioto, 1984) con alguien mucho más mar- escribió a los 17 años su pri- las tire a la basura. En lo único que pienso todo el daría un puñetazo Te ginal que ella, Satoshi. La mera novela, Install, con la extraña relación de ambos tiempo es en las cosas que quiero que los demás que ganó la 38ª edición del orbitará en torno a la obse- hagan por mí, sin considerar siquiera el hacer yo Premio Bungei, siendo adap- sión por una modelo caren- tada posteriormente a la te de sentido común y por el misma algo por ellos. gran pantalla en 2004. despertar sexual disfrazado Wataya alcanzó la fama en de violencia explícita. Una 2003 al recibir el premio novela que te invita a recor- Te daría literario más prestigioso de dar la capacidad de los ado- Japón, el Akutagawa, por la lescentes para los cambios presente novela Te daría un de humor y la necesidad de puñetazo. Contaba sólo con expresar cómo se sienten a un puñetazo 19 años, siendo la ganadora través de los medios menos Risa Wataya más joven en la historia de convencionales. -

Milkova, Stiliana. Side by Side

http://www.gendersexualityitaly.com g/s/i is an annual peer-reviewed journal which publishes research on gendered identities and the ways they intersect with and produce Italian politics, culture, and society by way of a variety of cultural productions, discourses, and practices spanning historical, social, and geopolitical boundaries. Title: Side by Side: Female Collaboration in Ferrante’s Fiction and Ferrante Studies Journal Issue: gender/sexuality/italy, 7 (2020) Author: Stiliana Milkova, Oberlin College Publication date: February 2021 Publication info: gender/sexuality/italy, “Invited Perspectives” Permalink: https://www.gendersexualityitaly.com/7-female-collaboration-ferrante Author Bio: Stiliana Milkova is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at Oberlin College (USA). Her scholarly publications include several articles on Russian and Bulgarian literature, numerous articles on Elena Ferrante, and the monograph Elena Ferrante as World Literature. She has translated from Italian works by Anita Raja, Antonio Tabucchi, and Alessandro Baricco, among others. She edits the online journal Reading in Translation and her public writing has appeared in Nazione Indiana, Michigan Quarterly Review, Asymptote, and Public Books. Abstract: This essay proposes that Elena Ferrante’s novels depict female friendship and collaboration as a literal and metaphorical positioning side by side that dislodges the androcentric, vertical hierarchies of intellectual labor, authorship, and (re)production. Further, it argues that the collaborative female practices in Ferrante’s fiction have engendered––or brought to light––collaborative female and feminist projects in Ferrante Studies and outside academia establishing a legacy of creative and authorial women. Thus a double creation of female genealogies is at work within Ferrante’s novels and in the critical field that studies them. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

Who Is Elena Ferrante?

Who is Elena Ferrante? Is it Anita Raja or Domenico Starnone (as recent reports have claimed)? Here’s what the Cogito semantic technology discovered when it compared Ferrante’s writing style with that of Anita Raja, Domenico Starnone, Marco Santagata and Goffredo Fofi. The name Elena Ferrante is known worldwide. While her best-selling four-part series known as the Neapolitan Novels has sold millions of copies around the world, the author’s true identity is still unconfirmed. According to the most recent research, Elena Ferrante could be Anita Raja, the award-winning translator who also works for Ferrante’s Italian publishing house Edizioni e/o. However, with no confirmation from Ferrante, Raja or the publishers, the question “Who is Elena Ferrante?” remains a mystery. At Expert System, this is just the sort of mystery that we love, because, without delving into matters of privacy, our analysis relies on the only real clues that we have: the language that Ferrante uses in her published works. And it is from this perspective that we explore the question: By analyzing the language and style of writing, who is Elena Ferrante? About the analysis The analysis was made using Expert System’s Cogito semantic technology to compare the literary style of Elena Ferrante (in Italian) with that of four of the most cited candidates behind the Ferrante pseudonym: Translator Anita Raja, Raja’s husband and author Domenico Starnone, novelist Marco Santagata and essayist Goffredo Fofi. (Note: The analysis was performed on the original Italian version of each -

View Syllabus Information

View Syllabus Information View Syllabus Information Even after classes have commenced, course descriptions and online syllabus information may be subject to change according to the size of each class and the students' comprehension level. Update History Print Course Information Year 2020 School School of Culture, Media and Society Course Title Contemporary Japanese Fiction in English Translation (TCS Advanced Seminar) Instructor YOSHIO, Hitomi Term/Day/Period spring quarter 01:Tues.2/02:Fri.2 Category Advanced Seminars (TCS) Eligible Year 2nd year and above Credits 2 Classroom Campus Toyama Course Key Course Class 2331519001 01 Code Main Language English Course LITJ261S Code First Academic Literature disciplines Second Academic Japanese Literature disciplines Third Academic Japanese Modern and Contemporary Literature disciplines Level Intermediate, developmental and Types of Seminar applicative lesson Syllabus Information Latest Update:2020/03/03 12:23:56 Course Outline This course offers students an opportunity to read contemporary Japanese fiction in English translation, published in a variety of international print and online venues. We will read a range of authors including Haruki Murakami, Yoko Ogawa, Hiromi Kawakami, Mieko Kawakami, and Yoko Tawada. Through a close study of the fiction as well as the publication venues, we will explore the diverse themes and styles of contemporary Japanese literature and how selected works have been introduced and circulated in the global market. The course will be conducted in English. Although the readings will be offered in English translation, you are encouraged to read the stories in the original Japanese as well. Objectives 1) Acquire exposure to contemporary Japanese fiction in English translation. -

My Brilliant Friend - Set Design.Pdf

My Brilliant Friend Ferrante Fever: This is how the world-wide media defined the sweeping wave of success triggered by the four novels by the author behind the pseudonym Elena Ferrante. A publishing success that brought the story of Elena and Lila to the top of the international bestseller lists. All thanks to a solid narrative structure that sets off the forms of the melodrama within complex psychologies rich in nuances, combined with a refined style and an extraordinary ability to evoke atmospheres and environments. And the setting itself is one of the strongest points of the Neapolitan quadrilogy: a Naples described in a most credible and detailed fashion, but never predictable. Our two main characters, at once antagonistic and complementary personalities who we first meet in the schoolroom, move on this fascinating stage. Elena, the narrating voice, is rational and determined, predestined for literature - but also profoundly fragile and in need of being looked after. Lila is her mentor, but also at times her worst enemy: she is quick-tempered and by nature a dominator (and seducer). It is precisely in these continuous dialectics between submissive friend and brilliant friend, two roles that Elena and Lila keep swapping, that a story that will accompany us through forty years takes shape. A chronicle with the epic pace of a great coming-of-age novel between betrayals, sudden revelations and a love that knows no end. Surrounding Elena and Lila, Italy and Naples, and a neighborhood that is a small world in itself, where passions and miseries are always extreme. A microcosm that breathes the atmosphere of the rest of Naples, but without ever seeing it. -

Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit

Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit SCHRIFTENVERZEICHNIS LIST OF PUBLICATIONS 出版物 Buchpublikationen – Books – 著書 Monographien – Authored Monographs –モノグラフ 2 Herausgeberschaft – Editorship – 編者・発行者 Einzelpublikationen – Individual Titles – 単行本編者 5 Reihen – Series Editorship – シリーズ編者・発行者 10 Übersetzungen – Translations – 翻訳 Übersetzungen in Buchform – Translated Books – 単行本翻訳 18 Nicht selbständig erschienene Übersetzungen – Translations 20 Published in Books or Periodicals – 単行本、雑誌などに載せられた 翻訳 Aufsätze – Scholarly Articles - 学術論文 Buchkapitel und Zeitschriftenbeiträge – Book Chapters and Journal 21 Articles – 単行本、雑誌に載せられた論文 Vorworte und Einleitungen – Prefaces and Introductions – 40 序文、前書き Nachworte – Epilogues and Postscripts – 後書き、解説 45 Lexikonartikel – Articles in Dictionaries – 辞典記事、解説、論説 46 Rezensionen – Reviews - 書評 Wissenschaftliche Rezensionen – Reviews in Academic Journals – 50 学術書評 Rezensionen in Zeitungen – Newspaper Reviews – 新聞書評 52 Zeitungsartikel und sonstige Publikationen – Newspaper Articles and Other Publications – 新聞、その他の記事 In westlichen Sprachen – In Western Languages – ドイツ語、英語など 59 In japanischer Sprache – In Japanese – 日本語 65 Sonstige kleine Veröffentlichungen 71 2 BUCHPUBLIKATIONEN – BOOKS –著書 Monographien – Authored Monographs –モノグラフ 1. Mishima Yukios Roman “Kyōko-no ie”: Versuch einer intratextuellen Analyse. Wiesba- den: Harrassowitz, 1976. 310 S. (Dissertation) Wissenschaftliche Rezensionen: Takahashi Yoshito. Kyōdai kyōyōbu-hō, 1977, S. 5–6. Takeda Katsuhiko. “Kaigai ni okeru Mishima Yukio zō”. Kokubungaku – kaishaku to -

Glynn, R. (2019). Decolonizing the Body of Naples: Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels

Glynn, R. (2019). Decolonizing the Body of Naples: Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. Annali d'italianistica, 37, 261-88. Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Annali d'italianistica, Inc. at http://www.ibiblio.org/annali/toc/2019.html . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Ruth Glynn Decolonising the Body of Naples: Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels Abstract: This article addresses the construction of Naples in Elena Ferrante!s “Neapolitan Novels” (2011–2014) with reference to Ramona Fernandez!s theorization of the “somatope.” It reads the relationship between Elena and Lila as a heuristic for that between the cultured “northern gaze” on Naples and the city as the object of that gaze, as constructed in the historical repertoire. Paying close attention to the ideological underpinnings of Elena!s educational trajectory and embodiment of national culture, I argue that the construction of Lila-Naples as an unruly subject is posited in order to be critiqued, in accordance with critical perspectives deriving from feminist and postcolo- nial theory. I conclude by highlighting the evolution of the values associated with Lila and Elena over the course of the tetralogy to facilitate the recuperation of Neapolitan alterity and to propose a new way of writing the city beyond the colonizing gaze of the cultural tradition. -

Being Normal Is Outlandish in the Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Being normal is outlandish in the Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata Dr.V. Vishnu Vardhan, Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bishop Heber College, Tiruchirappalli-17 [email protected] and Dr. Suresh Frederick, Associate Professor and UG Head, Department of English, Bishop Heber College, Tiruchirappalli-17 [email protected] During an interview in a smoky subterranean cafe in Jimbocho, Tokyo’s book district,Ms Muratais regarded as one of the most exciting contemporary writers in Japan. She mainly focuses on adolescent sexuality in her works. It includes asexuality, involuntary celibacy and voluntary celibacy. Her works are “Jyunyū (Breastfeeding)”, ” Gin iro no uta (Silver Song)”, “Mausu (Mouse)”, ” Hoshi gasūmizu (Water for the Stars)”, ”Hakobune (Ark)”, “Shiro-iro no machi no, sono hone no taion no (Of Bones, Of Body Heat, of Whitening City)”, “Tadaima tobira”, ” Satsujinshussan”, “Shōmetsusekai (Dwindling World)”, “Konbininingen (Convenience Store Woman)” and “Clean Breed (A Clean Marriage)”. Contemporary Japanese writers of Sayaka Murata - Hiromi Kawakami, Fuminori Nakamura, Hitomi Kanehara, Risa Wataya ,Hideo Furukaw, Mieko Kawakami, Nao-Cola Yamazaki and Ryu Murakami. “When something was strange, everyone thought they had the right to came stomping in all over your life to figure out why” (Murata, Convenience Store Woman 36). The tale began with a girl named Keiko Furukura, who was the protagonist of this short novel. She was a simple and normal innocent girl;she was living as a spinster. She never had a relationship even lovemaking. But she was happy with it. She recognized that she was being different from others. She decided to fit her in the machine of society. -

Catalog (Which Are Available for Your Immediate Use)

Princeton First Year Common Reading 2021 THINKING & SKILLS A lively and engaging guide to vital habits of mind that can help you think more deeply, write more effectively, and learn more joyfully How to Think like Shakespeare How to Think like Shakespeare offers an enlightening and entertaining guide to the craft of thought—one that demon- strates what we’ve lost in education today, and how we might begin to recover it. In fourteen brief, lively chapters that draw from Shakespeare’s world and works, and from other writers past and present, Scott Newstok distills vital habits of mind that can help you think more deeply, write more effectively, and learn more joyfully, in school or beyond. Written in a friendly, conversational tone and brimming with insights, How to Think like Shakespeare enacts the thrill of thinking on every page, reviving timeless—and timely—ways to stretch your mind and hone your words. “How to Think like Shakespeare is a witty and wise incitement “A lucid, human, terrifically engaging to shape our minds in old ways that will be new to almost all call to remember our better selves and of us.” a supremely unstuffy celebration of —Alan Jacobs, author of How to Think: A Survival Guide for what’s essential.” a World at Odds —Pico Iyer, author of The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere Scott Newstok is professor of English and founding director of the Pearce Shakespeare Endowment at Rhodes College. A parent and an award-winning teacher, he is the author of Quoting Death in Early Modern England and the editor of several other books.