A Saunter Through the Ages Down the Avenue Burghwallis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Deceased

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be notices of claims (Surname first) Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given SMITH, Sarah Emily Ruth 28 Berkeley Road, Bishopston, Bristol, Avon, K. W. J. Merrick, 262 Gloucester Road, Horfield, Bristol, BS7 8PB, Solicitor. 30th December 1976 Widow. 2nd August 1976. (Stanley Desmond Smith.) (144) ENGLAND, Nelly 16 Pleasant Road, Intake, Sheffield, Widow. Yorkshire Bank Limited, Trustee Department, Allerton House, 55 Harrogate 21st January 1977 4th September 1976. Road, Leeds, LS7 3RU. (145) MILLARD, Annie Hill View, Kicks Hill, Middlezoy, Widow. Lloyds Bank Limited, Taunton Trust Branch, 30 Fore Street, Taunton, Somerset, 30th December 1976 Elizabeth. 24th September 1976. TA1 1HW. (Lloyds Bank Limited and Eric Phillip Roger Foster.) (146) GEEN, Mary Alexandra Hospital, Barnstaple, North Devon, Slee, Blackwell & Slee, 14 Heanton Street, Braunton, N. Devon, EX33 2JT, 4th January 1977 W Spinster, llth October 1976. Solicitors. (Douglas Walter Blackwell.) (147) DENNIS, James ... Hill Park, Knowle, Braunton, Devon, Company Slee, Blackwell & Slee, 14 Heanton Street, Braunton, N. Devon, EX33 2JT, 4th January 1977 Director. 4th October 1976. Solicitors. (Norman James Dennis and Diana Ruth Dennis.) (148) McMASTER, James 77 Park Road, Hagley, Stourbridge, West Mid- Lloyds Bank Limited, Wolverhampton Trust Branch, 29 Waterloo Road, Wolver- 31st December 1976 lands, Engineer. 27th September 1976. hampton, West Midlands, WV1 4DE, or Thursfield, Messiter & Shirlaw, (149) 53 Lower High Street, Wednesbury, West Midlands, WS10 7AW. RHODES, William Cutshaw Farm, Laycock, Keighley, West York- Turner & Wall, Arcade Chambers, Keighley, West Yorkshire, Solicitors. -

Crabgate Lane, Skellow, Doncaster, Dn6 8Lb Offers in Region of £195,000

CRABGATE LANE, SKELLOW, DONCASTER, DN6 8LB OFFERS IN REGION OF £195,000 www.matthewjameskirk.co.uk [email protected] 01302 898926 SUPERB EXTENDED THREE BEDROOM SEMI- DETACHED HOME ON CRABGATE LANE IN SKELLOW. This fabulous house has been modernised, extended and updated throughout to provide a beautiful move in ready property. The open plan living/dining/kitchen is the main selling feature of the house with a central island and doors leading out to the immaculately presented gardens. The property in brief comprises of entrance hallway, living room with bay window, open plan kitchen/dining/living space, stairs, landing, three bedrooms, bathroom, driveway, detached single garage, plus front and rear gardens. A WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITY AND VIEWINGS ARE HIGHLY RECOMMENDED. ENTRANCE HALL 13' 3" x 5' 4" (4.06m x 1.64m) The front facing double glazed door leads to the lovely bright entrance hallway with stairs to the first floor, storage space beneath the stairs, radiator, front facing double glazed frosted window, coving to the ceiling and spotlights. LIVING ROOM 12' 4" x 9' 10" (3.77m x 3.00m) Bright and airy reception space with front facing double glazed bay window overlooking the front garden, radiator, coving to the ceiling, television point and a telephone point. KITCHEN/LIVING/DINING AREA 18' 0" x 18' 0" (5.51m x 5.49m) Fabulous extended part of the property which now provides a beautiful open plan entertaining space that any buyer would fall in love with, rear facing double glazed French doors to the patio, rear facing double -

Metacre Ltd (05173) (Crabgate Lane)

Ref: Doncaster Local Plan Publication Draft 2019 (For Official Use Only) COMMENTS (REPRESENTATION) FORM Please respond by 6pm Monday 30 September 2019. The Council considers the Local Plan is ready for examination. It is formally “publishing” the Plan to invite comments on whether you agree it meets certain tests a Government appointed independent Inspector will use to examine the Plan (see Guidance Notes overleaf). That is why it is important you use this form. It may appear technical but the structure is how the Inspector will consider comments. Using the form also allows you to register interest in taking part in the examination. All comments received will be sent to the Inspector when the plan is “submitted” for examination. Please email your completed form to us at If you can’t use email, hard copies can be sent to: Planning Policy & Environment Team, Doncaster Council, Civic Office, Doncaster, DN1 3BU. All of the Publication documents (including this form) are available at: www.doncaster.gov.uk/localplan This form has two parts: Part A – Personal Details and Part B – Your Comments (referred to as representations) Part A Please complete in full. Please see the Privacy Statement at end of form. 1. Personal Details 2. Agent’s Details (if applicable) Title Miss First Name Chris Last Name Calvert Organisation Metacre Limited Pegasus Group (where relevant) Address – line 1 Pavilion Court Address – line 2 Green Lane Address – line 3 Garforth, Leeds Postcode LS25 2AF E-mail Address Telephone Number Guidance Notes (Please read before completing form) What can I make comments on? You can comment (make representations) on any part of the Doncaster Local Plan Publication Version and its supporting documents. -

The Doncaster Green Infrastructure Strategy 2014- 2028

The Doncaster Green Infrastructure Strategy 2014- 2028 Creating a Greener, Healthier & more Attractive Borough Adoption Version April 2014 Doncaster Council Service Improvement & Policy (Regeneration & Environment) 0 1 the potential of the Limestone Valley, which runs through the west of the borough. Did you know that Doncaster has 65 different woodlands which cover an area in excess of 521 hectares? That’s about the equivalent to over 1,000 football pitches. There are 88 different formal open spaces across the borough, which include football, rugby and cricket pitches, greens, courts and athletics tracks. Doncaster is also home to 12 golf courses. The Trans-Pennine Trail passes through Doncaster and is integral to the extensive footpath and cycle network that link the borough’s communities with the countryside, jobs and recreation opportunities. There are so Foreword from the many more features across Doncaster and these are covered within this Strategy document. Portfolio Holder… Despite this enviable position that communities in Doncaster enjoy, there is always so much more that can be done to make the borough’s GI even greater. The Strategy sets out a framework As Portfolio Holder for Environment & Waste at for ensuring maximum investment and funding Doncaster Council, I am delighted to introduce is being channelled, both by the Council and the the Doncaster Green Infrastructure Strategy vast array of important partners who invest so 2014-2028: Creating a Greener, Healthier & much time and resources, often voluntarily, into more Attractive Borough. making our GI as good as it can be. As the largest metropolitan Borough in the This Strategy will help deliver a better country, covering over 220 square miles, connected network of multi-purpose spaces and Doncaster has an extensive green infrastructure provide the opportunity for the coordination (GI) network which includes numerous assets and delivery of environmental improvements and large areas that are rural in character. -

Local Environment Agency Plan

6 o x I local environment agency plan SOUTH YORKSHIRE & NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE FIRST ANNUAL REVIEW May 1999 BARNSLEY ROTHERHAM SHEFFIELD CHEST ELD E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE HEAD OFFICE Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West. Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD South Yorkshire & North East Derbyshire LEA P First Annua! Review SOUTH YORKSHIRE AND NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE AREA ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES W . 'H D i SwllhoJ* j Oram iRNSLEY DONCASTER ) ROTHERHAM SHEFFIELD (DERBYSHIRE DALES) KEY CHESTERF.IEUD) BOLSOVER - CATCWENT BOUNDARY RIVER ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARY MAIN ROAD SGRTH EAST \ 0 2 4 6 8 10km ___1 i_________ i_________ i_________ i_________ i Scale ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 032505 South Yorkshire & North East Derbyshire LEAP First Annual Review EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The South Yorkshire & North East Derbyshire LEAP First Annual Review reports on the progress made during the last year against LEAP actions. The actions published in the LEAP are supplemental to our everyday work on monitoring, surveying and regulating to protect the environment. Some of the key achievements on our everyday work include: i) In September 1998 Michael Clapham MP officially opened the Bullhouse Minewater Treatment Plant. The scheme is a pioneering £1.2m partnership project funded by European Commission, Coal Authority, Environment Agency, Hepworths Building Products, Barnsley MBC and Yorkshire Water. Within one week a visible reduction could be seen in ochre levels in the River Don, after more than 100 years of pollution. ii) Monckton Coke and Chemical Company have successfully commissioned a combined heat and power plant, costing approximately £7 million. -

The Boundary Committee for England

KEY THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND DISTRICT BOUNDARY PROPOSED DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF DONCASTER PARISH WARD COINCIDENT WITH OTHER BOUNDARIES PROPOSED WARD NAME ASKERN SPA WARD Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the Borough of Doncaster August 2003 Sheet 2 of 10 Sheet 2 "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. 1 2 3 4 Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD03114G" 5 6 7 8 Only Parishes whose Warding has been altered by these Recommendations have been coloured. 9 10 t n e W r e iv R y wa ail d R tle an sm Di Fenwick Fenwick Common N O R T O N A N D K IR K S M E A T O N R O A FENWICK CP D y wa ail d R tle an sm Di West Field Dryhurst Closes Went Lows Fenwick Common Norton South Field Schools Norton Common Norton Ings C l o u g h L a n e Def Fenwick Common Pond D Playing e Field Norton Ings f Moss & Fenwick County Primary Norton Common School Campsmount High School Spoil Heap Playing Field Greyhound Stadium Cemy U n d Barnsdale Church Field F E N W I Campsmount Park C K L A N Moss E NORTON CP Willow Garth Campsall Ch Def Askern Askern Allot Common Gdns Allot Burial Bridge Ground Gdns South Park Campsmount Park E G N A R G N R E K S A ASKERN CP Askern Def MOSS CP Def STAINFORTH AND MOORENDS WARD Limestone Quarry School Instoneville Barnsdale Allot Gdns School D ef Allot Gdns Haywood Common -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

Latest Publications List

Doncaster & District Family History Society Publications List December 2020 Parishes & Townships in the Archdeaconry of Doncaster in 1914 Notes The Anglican Diocese of Sheffield was formed in 1914 and is divided into two Archdeaconries. The map shows the Parishes within the Archdeaconry of Doncaster at that time. This publication list shows Parishes and other Collections that Doncaster & District Family History Society has transcribed and published in the form of Portable Document Files (pdf). Downloads Each Parish file etc with a reference number can be downloaded from the Internet using: www.genfair.co.uk (look for the Society under suppliers) at a cost of £6 each. Postal Sales The files can also be supplied by post on a USB memory stick. The cost is £10 each. The price includes the memory stick, one file and postage & packing. (The memory stick can be reused once you have loaded the files onto your own computer). Orders and payment by cheque through: D&DFHS Postal Sales, 18 Newbury Way, Cusworth, Doncaster, DN5 8PY Additional files at £6 each can be included on a single USB memory stick (up to a total of 4 files depending on file sizes). Example: One USB memory stick with “Adlingfleet” Parish file Ref: 1091 = £10. 1st Additional file at £6: the above plus “Adwick le Street” Ref: 1112 = Total £16. 2nd Additional file at £6: “The Poor & the Law” Ref: 1125 = Total £22 Postage included. We can also arrange payment by BACs, but for card and non-sterling purchases use Genfair Parishes Adlingfleet All Saints Ref: 1091 Revised 2019 Baptisms -

Doncaster Local Plan

Doncaster Local Plan Summary of Representations to Main Modifications Consultation 2021 and Council’s Response www.doncaster.gov.uk 1 Doncaster Local Plan Summary of Representations to Main Modifications Consultation 2021 and Council’s Response (April 2021) Consultation took place for six weeks between Monday 8 February until the end of Sunday 21 March 2021. The scope of the consultation was consistent with that undertaken at Regulation 19 stage. Consultation responses were received from the following individuals, site promoters and organisations: Individuals: Lund, Oliver; Mason, Gillian; Owen, Christopher; Parkinson, Don, Parkinson, Kim and Wilton (Thorne) Ltd; Thomson, Julia; Tomlinson, Stephen. Site promoters: Abernant Homes; Avant Homes, Bellway Homes; Blue Anchor Leisure; Firsure; Harworth Group; KCS Developments Limited; Metacre; Metroland; Miller Homes; Peel Land and Property Group Management; Persimmon Homes South Yorkshire; Polypipe Building Products; RWE Renewables UK Developments Ltd; Sandbeck Estate; Strata Homes; The Home Builders Federation; The Strategic Land Group; Troy Verdion; JVH Town Planning. Organisations: Anglian Water; Canal and River Trust; CrossCountry Trains; Environment Agency; Highways England; Historic England; Homes England; Natural England; NHS Property Services; The Coal Authority; United Kingdom Onshore Oil and Gas; Wakefield Council; Yorkshire Wildlife Trust. The Local Plan Inspector’s instructions in respect of this consultation (DONC INP22 MM consult) state the following: ‘the Council should forward the representations to the Programme Officer along with a report listing all of the representations; a summary of the main issues raised; and the Council’s brief response to those main issues.’ The summary and brief responses are provided in Tables A to E below. All the representations can be viewed in full on the Council’s Main Modifications page on the website at: www.doncaster.gov.uk/localplan. -

HOUSING B) ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION C) SHOPPING, SERVICES and TOWN and DISTRICT CENTRES D) ENVIRONMENT D) ACCESS and TRANPORTATION E) OTHER INFRASTRUCTURE

DONCASTER CORE STRATEGY CONSULTATION DRAFT October 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY GLOSSARY THE ROLE OF THE LDF AND CORE STRATEGY KEY ELEMENTS DONCASTER’S CHARACTERISTICS AND ISSUES DONCASTER’S VISION AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES BUILDING IN FLEXIBILITY IN THE CORE STRATEGY KEY DIAGRAM SPATIAL STRATEGY FOR DONCASTER a) SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY b) SUSTAINABLE SETTLEMENT STRATEGY c) AREA SPATIAL STRATEGIES BOROUGH WIDE POLICIES a) HOUSING b) ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION c) SHOPPING, SERVICES AND TOWN AND DISTRICT CENTRES d) ENVIRONMENT d) ACCESS AND TRANPORTATION e) OTHER INFRASTRUCTURE RESPONSE FORM APPENDICES - APPENDIX 1: PLANS - APPENDIX 2: IMPLENTATION, FLEXIBILITY, MONITORING AND MANAGEMENT - APPENDIX 3: OTHER POLICIES, STRATEGIES AND PLANS - APPENDIX 4: UDP POLICIES TO BE REPLACED BY CORE STRATEGY 1 DONCASTER CORE STRATEGY CONSULTATION DRAFT October 2008 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1. Why this document is needed Doncaster’s Core Strategy is part of the new Local Development Framework (LDF), which will replace the Unitary Development Plan which was adopted in 1998. The Core Strategy will set out broadly how it is proposed that Doncaster will develop over the 16 year period from its adoption in 2010 to 2025. The LDF will be the spatial expression of the Borough Strategy. The Core Strategy will set out major planning strategy and policy and locations for different types of development like housing, offices, mineral working and waste treatment plants across the borough – to transform Doncaster into an ‘Eco Borough’ based on a range -

Neutral and Wet Grassland (NWG)

Neutral and Wet Grassland (NWG) Habitat Action Plan Doncaster Local Biodiversity Action Plan January 2007 Table of Contents Page 1. Description 1 2. National status 5 3. Local status 6 4. Legal status 9 5. Links to associated habitats & species 10 6. Current factors causing loss or decline 11 7. Current local action 14 8. Objectives, targets & proposed actions 17 9. Indicative Habitat distribution & Opportunities map 29 Doncaster Biodiversity Action Partnership Doncaster Council, Environmental Planning, 2nd Floor, Danum House, St Sepulchre Gate, Doncaster, DN1 1UB. Telephone: 01302 862896 Email: [email protected] For further information please visit www.doncaster.gov.uk or contact; Doncaster Biodiversity Actionwww.doncaster.gov.uk/biodiversity Partnership, c/o Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council, Environmental Planning, Spatial Planning and Economic Development, Directorate of Development, 2nd Floor, Danum House, St Sepulchre Gate, Doncaster, DN1 1UB, Tel: 01302 862896, E-mail: [email protected] MM67-120 DONCASTER LOCAL BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN 1. Description 1.1 The low-lying clay and alluvial soils of the Humberhead Levels provide excellent conditions for intensive agricultural production. This landscape tends to be dominated by arable cultivation, improved grazing pastures and rye- grass leys, but some small pockets unimproved and semi-improved neutral grassland still survive. 1.2 The most diverse of these neutral grasslands are typically flower-rich hay meadows or pastures with a diversity of grasses and sedges such as common bent (Agrostis capillaries), sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum oderatum), quaking grass (Briza media), crested dog's-tail (Cynosurus cristatus), red fescue (Festuca rubra), Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus), cock's-foot (Dactylis glomerata), spring sedge (Carex caryophyllea), glaucous sedge (Carex flacca), and varying proportions of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). -

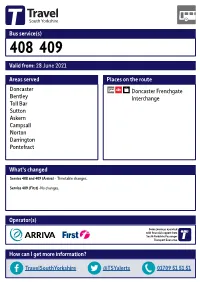

Valid From: 28 June 2021 Bus Service(S

Bus service(s) 408 409 Valid from: 28 June 2021 Areas served Places on the route Doncaster Doncaster Frenchgate Bentley Interchange Toll Bar Sutton Askern Campsall Norton Darrington Pontefract What’s changed Service 408 and 409 (Arriva) - Timetable changes. Service 409 (First) -No changes. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 408 and 409 27/07/2018# Ferrybridge Kellingley Knottingley Eggborough Hensall Pontefract, Bus Stn 408 409 Cridling Stubbs Great Heck Darrington, Darrington Hotel/ Whitley Pontefract, Crest Dr/ Manor Park Rise Woodland View Darrington Womersley, Main St Carleton, Carleton Rd/Green Ln 409 Womersley East Hardwick 409 Balne 408Ï 408Ð Wentbridge, Went Edge Rd/Jackson Ln Kirk Smeaton, Cemetery Wentbridge,Low Ackworth Wentbridge Rd/Wentbridge Ln Walden Stubbs Thorpe Audlin, Fox & Hounds/Thorpe Ln Wentbridge Kirk Smeaton Norton, West End Rd/Broc-O-Bank Fenwick Thorpe Audlin 408 408 409 Askern, Selby Rd/Campsall Rd Norton Badsworth Askern, Station Rd/High St Campsall, Old Bells/High St 408 Moss Upton Askern, Eden Dr/ Hemsworth 408 Instoneville, Coniston Rd Barnsdale Bar, Woodfield Rd/Warren House Sutton Rd/Alfred Rd North Elmsall Sutton Skelbrooke Burghwallis Instoneville, Sutton Rd/Manor Way Owston South Kirkby South Elmsall Skellow Carcroft Hampole Toll Bar Toll Bar, Doncaster Rd/Bentley Moor Ln Clayton Hooton Pagnell Woodlands Arksey Pickburn Brodsworth