Where the River Deepens: Exploring Place-Based Relationships Through the Swimming Hole Experience Elijah Sobel Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cruise Passengers' Rights & Remedies 2016

PANEL SIX ADMIRALTY LAW: THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 245 246 ADMIRALTY LAW THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 Submitted By: HON. THOMAS A. DICKERSON Appellate Division, Second Department Brooklyn, NY 247 248 ADMIRALTY LAW THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 By Thomas A. Dickerson1 Introduction Thank you for inviting me to present on the Cruise Passengers’ Rights And Remedies 2016. For the last 40 years I have been writing about the travel consumer’s rights and remedies against airlines, cruise lines, rental car companies, taxis and ride sharing companies, hotels and resorts, tour operators, travel agents, informal travel promoters, and destination ground operators providing tours and excursions. My treatise, Travel Law, now 2,000 pages and first published in 1981, has been revised and updated 65 times, now at the rate of every 6 months. I have written over 400 legal articles and my weekly article on Travel Law is available worldwide on www.eturbonews.com Litigator During this 40 years, I spent 18 years as a consumer advocate specializing in prosecuting individual and class action cases on behalf of injured and victimized 1 Thomas A. Dickerson is an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Department of the New York State Supreme Court. Justice Dickerson is the author of Travel Law, Law Journal Press, 2016; Class Actions: The Law of 50 States, Law Journal Press, 2016; Article 9 [New York State Class Actions] of Weinstein, Korn & Miller, New York Civil Practice CPLR, Lexis-Nexis (MB), 2016; Consumer Protection Chapter 111 in Commercial Litigation In New York State Courts: Fourth Edition (Robert L. -

Taking a Break Read, Listen and Talk About Holidays and Travel

Taking a break Read, listen and talk about holidays and travel. Practise passive forms. Focus on effective listening, interpreting statistics. Write a description of a place. GRAMMAR AND READING Work it out 1 Work in pairs. Look at the holiday brochure and 2 Match sentences 1–6 with their passive answer the questions. versions a–f in the texts below. • What is unusual about the three hotels it 1 They keep the temperature at about –5ºC. describes? 2 They are already accepting reservations. • Which of the hotels would you prefer to 3 Someone murdered two people while spend a night in? Why? someone else was building the castle. • Have you ever stayed in an unusual place? 4 The Clan McIntosh attacked the castle. 5 Since then they have completely rebuilt the hotel many times. 6 They won’t complete the complex until next TOP 3 year. Extraordinary Hotels Want a holiday with a difference? Castle Stuart Scotland 2 Castle Stuart, which was built about 400 years ago, has Have a look at these places … a violent history. c Two people were murdered while the castle was being built. Not long after the building was finally completed in 1625,d the castle was attacked by the Clan McIntosh and was abandoned. Since then it has been fully restored and is now a luxury hotel. But it is said that the bedroom at the top of the East Tower is haunted. 3 Poseidon Underwater 1 Resort The Bahamas The Icehotel Sweden The Poseidon is the world’s first underwater luxury 200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, Swedish hotel. -

Advice from Alumni LADSS 2016

Advice from LADSS Alumni (There’s a lot! We’ve had lots of students over the years.) Kevin Keller, 2015 1. Try to get a place at Canyon Village Apartments. They are the nicest. 2. Go to Mount Wheeler. 3. Go rock climbing Tuesday and Thursday with the Los Alamos mountaineers 4. If you like rock climbing go up to the Jemez close to the Caldera. It has some of the best rock climbing around. 5. Join the YMCA. They are the cheapest in town and have a climbing wall. 6. Make sure you read all of the material before you arrive. Kyle Neal, 2015 1. Finding housing should be your first order of business. I lived at Ponderosa Pines and had a great experience there. 2. Find a means to get in touch with other students before you arrive in Los Alamos. This will help organize housing and possibly transportation. 3. I drove my truck from Tennessee to Los Alamos and was glad I did. I would suggest bringing a vehicle, but there were many students who got along fine by riding the bus or carpooling. 4. Be prepared to learn. There is a lot of information thrown at you during the lectures. 5. If you are interested in graduate school, the summer school is a great opportunity to make connections with potential graduate advisors and other future graduate students. 6. By the end of the summer you will have accumulated a massive number of files and data; it will help everyone if you keep it well organized. 7. -

Guanacaste Activity Catalog 2019/2020 Mil Besos- Costa Rica

This document will help you to plan out your activities while in Costa Rica! Costa Rica has a ton to offer from surfing, to hiking, to white water rafting. Please do not hesitate to contact the team at Mil Besos at [email protected] or 1-877-888- 9151 Guanacaste Activity Catalog 2019/2020 Mil Besos- Costa Rica Guanacaste Activity Catalog 2019/2020 Children Includes (See key Tour Name (Descriptions of each are in the back of the document) Adult Rate Rate below) Arenal Volcano One Day Tour & Baldí (1) 175 140 E/L/P/D Arenal Volcano One Day Tour & Ecotermales (1) 206 165 E/L/P/D Arenal Volcano One Day Tour & The Springs (1) 234 187 E/L/P/D Arenal Volcano One Day Tour & Tabacón (1) 223 156 E/L/P/D Barra Honda Caves (Spelunking) 165 165 E/L/P Beach Tour & Snorkeling 108 97 L/P Beach Tour & Surf Lessons 180 162 L/P Borinquen Adventure Day (Canopy + Horseback + Lunch + Hot Springs) 160 112 E/L/P Borinquen Adventure Day Full (HB+ZL+WAT+HS) (7) 169 118 Buena Vista Mega Combo Adventure 155 125 E/L/P Buena Vista Extremo 170 137 E/L/P Canyon Lodge Adventure Combo 155 140 P Class 2&3 White Water Rafting (2) 125 100 E/L/P Class 3&4 White Water Rafting (Tenorio Rafting) (2) 140 140 E/L/P Early Bird Watching Tour 79 63 P/S Forest & Beach Horseback Riding @ Conchal Beach (10) 90 90 P/S Horseback Riding @ Papagayo area (5) 90 90 P/S Liberia City & Shopping Tour 79 63 P Monteverde Cloud Forest Experience (Coffee Tour & Hanging Bridges) 190 152 E/L/P/D Monteverde Cloud Forest Experience (Coffee Tour, Sky Tram & Canopy Zipline Tour.) 210 168 E/L/P/D -

Spain: Climbing, Canyoning, & Coasteering

Adventure Travel Spain: Climbing, Canyoning, & Coasteering September 1-9, 2018 More Information https://www.cmc.org/AdventureTravel/AdventureTravelTrips/SpainAdventure.aspx Trip Summary: • 2.5 days of rock climbing • 1.5 days of canyoning • 2 x 0.5 days of via ferrata • 2 days of coasteering Prerequisites: No previous experience necessary. For Coasteering you must be able to swim. Day 0: Fly to Valencia Airport (VLC) Day 1 – September 1: Arrive Valencia, transfer to Costa Blanca, possible via ferrata based on time availability Day 2 – September 2: RocK Climbing Day 3 – September 3: Canyoning Day 4 – September 4: Coasteering Day 5 – September 5: Via Ferrata + RocK Climbing Day 6 – September 6: RocK Climbing Day 7 – September 7: Via Ferrata + Canyoning Day 8 – September 8: Coasteering Day 9: - September 9: Optional via ferrata. Departing flights from Valencia (VLC) 2 Day 0: Fly to Valencia, Spain (VLC - Valencia Airport) Day 1: Arrive Valencia, transfer to Costa Blanca Description: Meet and greet at Valencia Airport (VLC). Transfer to the Costa Blanca in rental van. From Valencia we will drive 1.5-2hr south where we will check-in at our bungalows on the Costa Blanca. Depending on what time the flight arrives we may be able to squeeze in a via ferrata on our way to the Costa Blanca. Difficulty of Via Ferrata: Lunch: On your own. We will stop to buy food and snacks. Dinner: Welcome dinner included at local restaurant with local Valencian food. Sleep: Included at bungalows on the northern Costa Blanca (2-4 people per bungalow). 3 Day 2: Rock Climbing Description: We spend today rocK climbing on some of the finest limestone in Spain. -

Travel Essential Activities Document (PDF 55KB)

Standard activities With our Essential cover, you’re covered to do the following activities while on a trip. There is no cover under this policy for any sporting activity where money is paid to you to take part, or for any kind of manual work. • Archery • Paintballing if you wear eye protection • Badminton • Parascending or parasailing over water (once only and if fully • Banana boating supervised by a person experienced in this activity) • Baseball • Pony trekking • Basketball • Rambling • Body and boogie boarding • Roller skating and roller-blading • Bowls and bowling • Rowing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Bungee jump (once only and if fully supervised by a person • Running experienced in this activity) • Safari trekking as part of an organised tour • Cricket • Scuba diving to a depth of 18 metres if you are diving with another • Cruise activities that are organised by the cruise company and take person and you both hold a certificate of proficiency, or you are diving part on the cruise vessel with a qualified instructor in this profession but not within 24 hours of a flight • Curling • Skateboarding if you wear a helmet • Cycling but not BMX or mountainbiking (other than normal road cycling using a mountain bike) or racing • Sledging or sleigh riding if you are a passenger and being pulled by dogs, horses or reindeer • Dinghy sailing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Snorkelling • Fishing • Softball or rounders • Football (including soccer, 5-a-side, Gaelic, Footbag, Hacky Sack, indoor and beach) • Squash • Go-karting if you wear a helmet and follow the organiser’s guidelines • Swimming no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Golf • Table tennis • Ice skating on a rink and not speed or inline skating • Tennis • Jogging • Trekking, hiking or fell walking up to 2500 metres •Orienteering • Volleyball • Paddle boarding Unfortunately we can’t cover any activity or sporting activity that you are paid to take part in. -

Pioneer Adventure Tour

+91-8048371905 Pioneer Adventure Tour https://www.indiamart.com/pioneer-adventure-tours/ Pioneer adventure tours was Established Aug 15th in Shillong with the prime intent to introduce and expose adventure sports in the state of Meghalaya and the North East as a whole. Starting Pioneer Adventure tours made sense simply because there was ... About Us Pioneer adventure tours was Established Aug 15th in Shillong with the prime intent to introduce and expose adventure sports in the state of Meghalaya and the North East as a whole. Starting Pioneer Adventure tours made sense simply because there was a lack of qualified professionals providing people with the opportunity to explore and discover Meghalaya's rich and diverse natural environment. Our first adventure site is situated in Dawki (which borders Bangladesh) and provides adventure activities like scuba diving, trekking, river rafting, cliff jumping, zip lining, caving, rock climbing, canyoning and camping. We intend to have people stay on site for a couple of days and take part in the various adventure activities on offer. Most of our team is experienced in the adventure activities we offer, with certified qualifications in scuba diving from PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) as well as mountaineering and rock climbing from the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering. Jason is a certified rock climber, having passed out from Wee's Rock Climbing School, Thailand. Jason and Vijay have been part of major river rafting expeditions, and Gary is a highly experienced mountaineer, having summited Mt Cho Oyu in Tibet and most recently, Stok Kanrgi in Leh, Ladakh. He has also climbed Mt. -

Standard Activities Adventure Activities

Standard activities With both our Essential and Premier policies, you’re covered to do the following activities while on a trip. There is no cover under this policy for any sporting activity where money is paid to you to take part, or for any kind of manual work. • Archery • Paintballing if you wear eye protection • Badminton • Parascending or parasailing over water (once only and if fully • Banana boating supervised by a person experienced in this activity) • Baseball • Pony trekking • Basketball • Rambling • Body and boogie boarding • Roller skating and roller-blading • Bowls and bowling • Rowing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Bungee jump (once only and if fully supervised by a person • Running experienced in this activity) • Safari trekking as part of an organised tour • Cricket • Scuba diving to a depth of 18 metres if you are diving with another • Cruise activities that are organised by the cruise company and take person and you both hold a certificate of proficiency, or you are diving part on the cruise vessel with a qualified instructor in this profession but not within 24 hours of a flight • Curling • Skateboarding if you wear a helmet • Cycling but not BMX or mountainbiking (other than normal road cycling using a mountain bike) or racing • Sledging or sleigh riding if you are a passenger and being pulled by dogs, horses or reindeer • Dinghy sailing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Snorkelling • Fishing • Softball or rounders • Football (including soccer, 5-a-side, Gaelic, Footbag, Hacky Sack, indoor and beach) • Squash • Go-karting if you wear a helmet and follow the organiser’s guidelines • Swimming no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Golf • Table tennis • Ice skating on a rink and not speed or inline skating • Tennis • Jogging • Trekking, hiking or fell walking up to 2500 metres •Orienteering • Volleyball • Paddle boarding Adventure activities (Premier cover only) With our Premier cover, you’re also covered to do the following activities while on a trip. -

2008 Uk Dissertation Michal Gajda

Napier University MSc Tourism and Hospitality Management Masters Dissertation SESSION 2007/8 TITLE U.K. MOUNTAIN BIKING TOURISM – AN ANALYSIS OF PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS, TRAVEL PATTERNS AND MOTIVATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF ACTIVITY AND ADVENTURE TOURISM AUTHOR MICHAL SZYMON GAJDA 06007138 Supervisor: Ros Sutherland 1 U.K. MOUNTAIN BIKING TOURISM – AN ANALYSIS OF PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS, TRAVEL PATTERNS AND MOTIVATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF ACTIVITY AND ADVENTURE TOURISM by M.S. Gajda May, 2008 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science in Tourism and Hospitality Management 2 Confidentiality in Use of Data Provided by Third Parties The data received from the organisations listed below have been used solely in the pursuit of the academic objectives of the work contained in this Dissertation and has not and will not be used for any other purpose outwith that agreed to by the provider of the data. Name (Print): Michal Szymon Gajda Signature:________________________________________________ Date: 28 May 2008 List of Data Providers VisitScotland Forestry Commission of Great Britain International Mountain Biking Association (IMBA) UK IMBA UK registered members 3 Declaration I declare that the work undertaken for this MSc Dissertation has been undertaken by myself and the final Dissertation produced by me. The work has not been submitted in part or in whole in regard to any other academic qualification. Title of Dissertation: UK Mountain Biking Tourism – an Analysis of Participant Characteristics, Travel Patterns, and Motivations in the Context of Activity and Adventure Tourism Name (Print): Michal Szymon Gajda Signature: _____________________________________________ Date: 28 May 2008 4 Acknowledgements Collecting the present research would not be possible without all the dedicated IMBA UK members who gave their time to complete the survey, thus many thanks go to them. -

How to Get Into Stunts

1 The professional stunt industry is a highly competitive field in the film world. It is a tightly knit community of professional race car drivers, world-class martial artists, gymnasts, dancers, circus performers, motocross racers, professional skateboarders and the list goes on. Needless to say, it is also extremely difficult to break into. As a potential stunt performer, you should have something extraordinary to offer the industry. Unfortunately, frequent gym visits, yoga, running, weightlifting and the like simply aren’t enough. There is the occasional “natural athlete” who succeeds but, for the most part, stunt performers come to the job with something major under their belts. In terms of training, there are tons of courses or sports you can sign up for that will help you along your path to becoming a stunt performer — take stunt driving courses, get your motorcycle license, and SCUBA ticket. Train at rock climbing, gymnastics, dirt biking, martial arts, trampoline, circus school, inline skating, diving, cliff jumping, etc. Take courses in acting, rigging, firearms handling and work with all kinds of weapons — there are literally unlimited things you can do to develop your career. The more specific skills you have to offer, the better. A good question to ask someone who wants to get into stunts is, “What is the skill set that you are offering to the industry?” All too often the answer is “I don’t really do anything specific but I’m crazy! I’ll do anything!” Translation: I’m unqualified, irrational and willing to take risks. Great. Except that a stunt performer’s job is to maximize the safety and minimize the risk in an action performance through knowledge, training and experience. -

MIT SUMMIT from Skiing, Snowboarding and Mountaineering Experiences

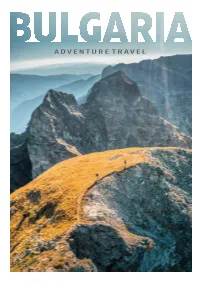

Bulgaria boasts the full range of terrains, landscapes and opportunities for adventure any outdoor enthusiast may dream of. Mountains rising over 2,900 m, more FROM SUMMIT than 200 mountain lodges and over 300 alpine lakes, clearwater rivers and canyons, tens of thousands of kilometres of marked hiking trails, a well-developed system of TO SEA protected areas, and more than 300 km of coastline. ADVENTURE TRAVEL ADVENTURE TRAVEL ADVENTURE Every time of the year brings new adventure. In spring we open the rafting, kayaking and FOUR canyoning season along high-water rivers, we climb old and new routes, we marvel at the sheer scale of bird migration, and we pitch camp for a long, nine-month season that’s also great for SEASONS cycling throughout. In summer we hike through cool ancient forests, we balance on challenging rocky arêtes, we fly, we surf, we dive and enjoy plunging in water. In autumn we are still high up in the mountains, hiking and trekking, and we continue camping. Winter rewards us with great skiing, snowboarding and mountaineering experiences. bulgariatravel.org ADVENTURE TRAVEL bulgariatravel.org 360mag.bg hiking-bulgaria.com stenata.com 2021 ADVENTURE TRAVEL IN BULGARIA - AIR - CONTENTS 74 PARA-/ HANG GLIDING Sopot 75 SKYDIVING Montana - HIGHLIGHTS - 76 BUNGEE 6 FROM SEA TO SUMMIT 77 HOT-AIR BALLOONS FOUR SEASONS 8 - MOUNTAINS - - CYCLING - 32 NATURAL DIVERSITY 58 MARKED/TRACKED ROAD AND MOUNTAIN BIKE ROUTES 34 MOUNTAIN LODGES AND SPORTS CENTRES Rudopia Belmeken High-Altitude Sports Complex Trans- Rhodope Bike Trail Malyovitsa -

Summerprog21.Pdf

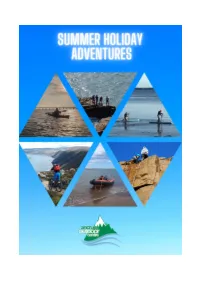

Week One Activity Wet Water Gorge Adventure Date Monday 28th June, 2021 Price £40 Age Age 8-11 years Description You will head up to West Water Gorge, Edzell and gorge scramble through a section of mountain stream where you encounter waterfalls, pools, chutes, rocky steps, holes, slides and often jumps and floating in rapids. Activity Faskally Fun Adventure Date Monday 28th June, 2021 Price £40 Age Age 12-16 years Description Come and enjoy a water fun-packed adventure day with the Ancrum team at Faskally. Activities will include rafting, adventure swimming and cliff jumping. Activity Mountain Biking Trail Centre Adventure Date Tuesday 29th June, 2021 Price £40 Age Age 8-11 years Description Scotland is a world class destination with something to offer all mountain bikers, from purpose-built trails to natural, wild routes amongst the great landscapes. Ancrum's mountain bike adventure will provide introductory tuition to the sport at one of an excellent range of mountain biking trails. centres and parks with well-maintained pathways and manmade jumps to practise on. Once you're ready you can get on with the matter in hand - having fun and enjoying an adventure! Activity Rock Climb and Abseil Adventure Date Tuesday 29th June, 2021 Price £40 Age Age 12-16 years Description Book onto this climbing and abseiling activity day with Ancrum where you will get the chance to climb a real crag and abseil from the top! Activity Stand-Up Paddleboarding Loch Adventure Date Wednesday 30th June, 2021 Price £40 Age Age 8-11 years Description Fancy trying one of the most popular water sport that is all the craze right now.