Article: Comedy Studies 'Women Like Us?' Dr Gilli Bush-Bailey Reader In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Virtual Quiz Quiz Two

Great Virtual Quiz Quiz Two Round 1 – Entertainment 1. For the 2019 Guide Dogs Appeal which entertaining duo were our campaign pups named after? a) Mel & Sue b) Morecambe & Wise c) Ant & Dec – Answer d) French & Saunders Fun fact: Ant always stands on the left and Dec on the right. They call this the 180-degree rule. 2. What was the occupation of the character Ross in Friends played by David Schwimmer? a) Orthodontist b) Archaeologist c) Palaeontologist – Answer d) Astronomer Fun fact: Columbia State University actually has a Palaeontology Professor called Dr David Schwimmer! 3. Who will be replacing Sandi Toksvig to present alongside Noel Fielding on the next series of The Great British Bake Off? a) Miranda Hart b) Davina McCall c) Matt Lucas – Answer d) Russell Brand Fun fact: Each day before filming begins on the Bake Off the ovens are checked for temperature and a Victoria Sponge is baked in each one to check it's working correctly. 4. Which singer has reached number one in the charts with his duet ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ with 99-year-old fundraising hero Captain Tom Moore? a) Robbie Williams b) Michael Ball – Answer c) Alfie Boe d) Aled Jones Fun fact: Tom Moore is the oldest person to have a number one song in the UK charts. 5. What would you be watching if you saw Tommy Shelby on the screen? a) Magnum PI b) Peaky Blinders – Answer c) Eastenders d) Killing Eve Round 2 – Disney 1. In the Little Mermaid what are the names of Ursula’s two eels? a) Slippy & Slidey b) Ebb & Flo c) Flotsum & Jetsum – Answer d) Salty & Sandy Fun fact: In the Little Mermaid there are hidden cameos from Mickey, Goofy, Donald Duck and Kermit the Frog. -

Humour Investigation: an Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French

Humour Investigation: An Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French Thursday, 10 May 2007 Nationally acclaimed former cartoonist and short story writer for The New Yorker, James Thurber, said that “the wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; [and] the humorist makes fun of himself” (Moncur, 2007, p. 1). Despite his misogynistic pronoun usage and the obviously unforgivable atrocity of overly Americanizing the spelling of 'humourist,' he did nicely categorize three of the methodological approaches to comedic targets. What Thurber didn't account for, however, were those comedians and comediennes who pay little to no regard for the socially constructed boundaries in form; he didn't account for the wildly transcendental Dawn French. Dawn French was born in October of 1957 in Wales and since early adulthood she has honed her humour skills through numerous television performances, a largely successful sitcom, and feature-length films with her comedic partner in crime Jennifer Saunders (Wikipedia, 2007). Though she started her career in a non- mainstream vain of comedy in the UK, her first major public debut was her starring role as Geraldine Granger on BBC1's 1990s smash situational comedy, The Vicar of Dibley (Wikipedia, 2007). Thus, the majority of her comedy has taken place in very recent times—the mid-to-late 90s and on into the current decade. While she utilizes many different comedic modes and forms, French's humour largely revolves around a few central themes and consequent philosophies. When investigating those themes, it is necessary to view her career as being dichotomously split into the Vicar of Dibley era and the subsequent post-Vicar epoch. -

4. UK Films for Sale at EFM 2019

13 Graves TEvolutionary Films Cast: Kevin Leslie, Morgan James, Jacob Anderton, Terri Dwyer, Diane Shorthouse +44 7957 306 990 Michael McKell [email protected] Genre: Horror Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Director: John Langridge Home Office tel: +44 20 8215 3340 Status: Completed Synopsis: On the orders of their boss, two seasoned contract killers are marching their latest victim to the ‘mob graveyard’ they have used for several years. When he escapes leaving them no choice but to hunt him through the surrounding forest, they are soon hopelessly lost. As night falls and the shadows begin to lengthen, they uncover a dark and terrifying truth about the vast, sprawling woodland – and the hunters become the hunted as they find themselves stalked by an ancient supernatural force. 2:Hrs TReason8 Films Cast: Harry Jarvis, Ella-Rae Smith, Alhaji Fofana, Keith Allen Anna Krupnova Genre: Fantasy [email protected] Director: D James Newton Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 7914 621 232 Synopsis: When Tim, a 15yr old budding graffiti artist, and his two best friends Vic and Alf, bunk off from a school trip at the Natural History Museum, they stumble into a Press Conference being held by Lena Eidelhorn, a mad Scientist who is unveiling her latest invention, The Vitalitron. The Vitalitron is capable of predicting the time of death of any living creature and when Tim sneaks inside, he discovers he only has two hours left to live. Chased across London by tabloid journalists Tooley and Graves, Tim and his friends agree on a bucket list that will cram a lifetime into the next two hours. -

This Week's TV Player Report

The TV Player Report A beta report into online TV viewing Week ending 17th January 2016 Table of contents Page 1 Introduction 2 Terminology 3 Generating online viewing data 4 Capturing on-demand viewing & live streaming 5 Aggregate viewing by TV player (On-demand & live streaming) 6 Top channels (Live streaming) 7 Top 50 on-demand programmes (All platforms) 9 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Android apps) 11 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Apple iOS apps) 13 Top 50 on-demand programmes (Website player) 15 Top 10 on-demand programmes by TV player 18 Frequently asked questions Introduction In an era of constant change, BARB continues to develop its services in response to fragmenting behaviour patterns. Since our launch in 1981, there has been proliferation of platforms, channels and catch-up services. In recent years, more people have started to watch television and video content distributed through the internet. Project Dovetail is at the heart of our development strategy. Its premise is that BARB’s services need to harness the strengths of two complementary data sources. - BARB’s panel of 5,100 homes provides representative viewing information that delivers programme reach, demographic viewing profiles and measurement of viewers per screen. - Device-based data from web servers provides granular evidence of how online TV is being watched. The TV Player Report is the first stage of Project Dovetail. It is a beta report that is based on the first outputs from BARB working with UK television broadcasters to generate data about all content delivered through the internet. This on-going development delivers a census- level dataset that details how different devices are being used to view online TV. -

Dispatches: Representatives

1 TIMECODE NAME Dialogue MUSIC 00.00.01 NARRATOR This is the BBC academy podcast, essential listening for the production, journalism and technology broadcast communities. Your guide to everything from craft skills, to taking your next step in the industry. 00.00.13 CHARLES Hello, I’m Charles Miller, this week we’re hearing about the world of television comedy from one of its most successful practitioners, Jon Plowman. If you haven’t heard of him don’t worry, he’s a producer not a performer but his work includes plenty of shows you will have heard of. French and Saunders, the Vicar of Dibley, Absolutely Fabulous, The Office, W1A and there are plenty more. At an event for the Media Society, Jon Plowman was interviewed by journalist Phil Harding, Jon offered his take on scripts, stars and what makes a great sitcom. 00.00.47 CHARLES Phil started by asking about Jon’s comic roots, which were back in school, he was no good at sport but he could make people laugh but he never expected that to turn into a career. 00.00.59 JON I didn’t spend my life thinking I want to make people laugh, if I thought anything, particularly a bit later than school, end of school I thought I want to be a theatre director and I was lucky enough to get a job early on at the Royal Court Theatre, with a wonderful guy called Lindsay Anderson, who made, if you’re old enough, movies like If and Oh Lucky Man and was a very, very good theatre director. -

Sally Chattaway Photo: London Headshots

59 St. Martin's Lane London WC2N 4JS Phone: 0207 836 7849 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nikiwinterson.com Sally Chattaway Photo: London Headshots Playing Age: 46 - 50 years Greater London, England, United Kingdom Appearance: Scandinavian, White Location: Surrey, England, United Eye Colour: Blue Kingdom Hair Colour: Blond(e) Kent, England, United Kingdom Hair Length: Long Height: 5'5" (165cm) Voice Quality: Bright Weight: 9st. (57kg) Voice Character: Enthusiastic Stage 2012, Stage, Sheila, In The Gloaming, Leicester Square Theatre, Nathaniel Tapley 2009, Stage, Various, Off Your Chest, Dirty Blondes - Lowdown at the Albany, Nathaniel Tapley 2006, Stage, Writer/Performer, Dirty Blondes at The Pleasance, Dirty Blondes, Fiona Finlay 2005, Stage, Candy Starr, One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest, Really Useful Group, Terry Johnson / Tamara Harvey 2004, Stage, Maxine, Stepping Out, The Mill at Sonning, Sally Hughes 2003, Stage, Various female roles, Committed Exhibitionists, Gilded Balloon, Fiona Finlay/Sally Chattaway 2002, Stage, Irene Wilson, Under the Yum Yum Tree, The Mill at Sonning, Ian Masters 2001, Stage, Valerie, Business Affairs, Swallow Productions/No 1 Tour, John B. Hobbs 2001, Stage, Various roles, Johnny Ball's Tales of Blooming Science, JB Productions, Johnny Ball 2000, Stage, The Stripper & U/S for Mrs Robinson & Mrs Braddock, The Graduate, Gielgud Theatre, Terry Johnson 1999, Stage, Brooke Ashton, Noises Off, Frankfurt English Theatre, Phil Young 1998, Stage, Brenda, A Bed Full Of Foreigners, Vienna English Theatre, Chris -

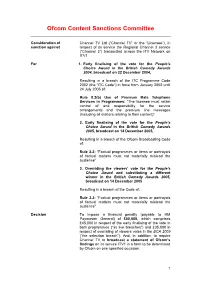

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee Consideration of Channel TV Ltd (“Channel TV” or the “Licensee”), in sanction against respect of its service the Regional Channel 3 service (“Channel 3”) transmitted across the ITV Network on ITV1. For 1. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2004, broadcast on 22 December 2004, Resulting in a breach of the ITC Programme Code 2002 (the “ITC Code”) in force from January 2002 until 24 July 2005 of: Rule 8.2(b) Use of Premium Rate Telephone Services in Programmes: “The licensee must retain control of and responsibility for the service arrangements and the premium line messages (including all matters relating to their content)” 2. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005, Resulting in a breach of the Ofcom Broadcasting Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” 3. Overriding the viewers’ vote for the People’s Choice Award and substituting a different winner in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005 Resulting in a breach of the Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” Decision To impose a financial penalty (payable to HM Paymaster General) of £80,000, which comprises £45,000 in respect of the early finalising of the vote in both programmes (“as live breaches”) and £35,000 in respect of overriding of viewers votes in the BCA 2005 (“the selection breach”). -

Rts Announces Winners for the Programme Awards 2009

P R E S S R E L E A S E Tuesday16 March 2010 RTS ANNOUNCES WINNERS FOR THE PROGRAMME AWARDS 2009 The Royal Television Society (RTS), Britain’s leading forum for television and related media, has announced the winners for the RTS Programme Awards 2009. The ceremony, held at Grosvenor House on Tuesday 16 March, was hosted by actor, comedian and radio presenter Rob Brydon and the awards were presented by RTS Chair, Wayne Garvie. The RTS Programme Awards celebrate all genres of television programming, from history to soaps, children's fiction to comedy performance. Covering both national and regional output, as well honouring the programmes themselves, they aim to recognise the work of exceptional actors, presenters, writers and production teams. The Winners: Scripted Comedy The Thick of It BBC Productions for BBC Two “An acerbic, intelligent and sweeping comedy which attained new heights. Faultless ensemble acting, meticulous writing and intricately contrived comedy climaxes combined to make this a series we didn‟t want to end.” Nominees Miranda BBC Productions for BBC Two The Inbetweeners A Bwark Production for E4 Entertainment Newswipe with Charlie Brooker Zeppotron for BBC Four “Right on the money... Refreshingly polemical and with real authenticity.” Nominees Britain's Got Talent A talkbackTHAMES and SYCO TV Production for ITV1 The X Factor A talkbackTHAMES and SYCO TV Production for ITV1 2-6 Northburgh Street, London EC1V 0AY +44 (0) 20 7490 4050 www.franklinrae.com Daytime and Early Peak Programme Come Dine With Me ITV Studios for -

Idub – the Potential of Intralingual Dubbing in Foreign Language Learning: How to Assess the Task

Language Value July 2017, Volume 9, Number 1 pp. 62-88 http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2017, ISSN 1989-7103 iDub – The potential of intralingual dubbing in foreign language learning: How to assess the task Noa Talaván [email protected] Tomás Costal [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Spain ABSTRACT Research on the use of active dubbing activities in foreign language learning is gaining an increasing amount of attention. The most obvious skill to be enhanced in this context is oral production and a few authors have already mentioned the potential benefits of asking students to record their voices in a ‘semi- professional’ manner. The present project attempts to assess the potential of intralingual dubbing (English-English) to develop general oral production skills in adult university students of English B2 level in an online learning environment, and to provide general guidelines of dubbing task assessment for practitioners. To this end, a group of undergraduate pre-intermediate students worked on ten sequenced activities using short videos taken from an American sitcom over a period of two months. The research study included language assessment tests, questionnaires and observation as the basic data gathering tools to make the results as reliable and thorough as possible for this type of educational setting. The conclusions provide a good starting point for the establishment of basic guidelines that may help teachers implement dubbing tasks in the language class. Keywords: Audiovisual translation, dubbing, language learning, oral skills, online tasks, assessment rubric I. INTRODUCTION The iDub – Intralingual Dubbing to Improve Oral Skills project arose from the need to evaluate the potential didactic efficiency of dubbing as an active task in distance foreign language (henceforth, L2) environments as well as from the lack of assessment materials in this learning context. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: In the second half of 1598 or 99 -- no later because the role of Dogberry was sometimes replaced by the name of “Will Kemp”, the actor who always played the role; Kemp left the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1599. AGE: 34-35 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Seventh in the line of Comedies after “The Two Gentlemen of Verona”, “The Comedy of Errors”, “Taming of the Shrew”, “Love’s Labours Lost”, “A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream”, “The Merchant of Venice”. QUARTO: A Quarto edition of the play appeared in 1600. GENRE: “Tragicomic” SOURCE: “Completely and entirely unhistorical” VERSION: The play is “Shakespeare’s earliest version of the more serious story of the man who mistakenly believes his partner has been unfaithful to him”. (“Othello” for one.) SUCCESS: There are no records of early performances but there are “allusions to its success.” HIGHLIGHT: The comedy was revived in 1613 for a Court performance at Whitehall before King James, his daughter Princess Elizabeth and her new husband in May 1613. AFTER: Oddly, the play was “performed only sporadically until David Garrick’s acclaimed revival in 1748”. CRITICS: 1891 – A.B. Walkley: “a composite picture of the multifarious, seething, fermenting life, the polychromatic phantasmagoria of the Renaissance.” 1905 – George Bernard Shaw: “a hopeless story, pleasing only to lovers of the illustrated police papers BENEDICTS: Anthony Quayle, John Gielgud, Michael Redgrave, Donald Sinden BEATRICES: Peggy Ashcroft, Margaret Leighton, Judi Dench, Maggie Smith RECENT: There was “a boost in recent fortunes with the well-received 1993 film version directed by Kenneth Branagh and starring Branagh and Emma Thompson.” SETTING: Messina in northeastern Sicily at the narrow strait separating Sicily from Italy. -

Mckinney Macartney Management Ltd

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd AMY ROBERTS - Costume Designer THE CROWN 3 Director: Ben Caron Producers: Michael Casey, Andrew Eaton, Martin Harrison Starring: Olivia Colman, Tobias Menzies and Helena Bonham Carter Left Bank Pictures / Netflix CLEAN BREAK Director: Lewis Arnold. Producer: Karen Lewis. Starring: Adam Fergus and Kelly Thornton. Sister Pictures. BABS Director: Dominic Leclerc. Producer: Jules Hussey. Starring: Jaime Winstone and Samantha Spiro. Red Planet Pictures / BBC. TENNISON Director: David Caffrey. Producer: Ronda Smith. Starring: Stefanie Martini, Sam Reid and Blake Harrison. Noho Film and Television / La Plante Global. SWALLOWS & AMAZONS Director: Philippa Lowthorpe. Producer: Nick Barton. Starring: Rafe Spall, Kelly Macdonald, Harry Enfield, Jessica Hynes and Andrew Scott. BBC Films. AN INSPECTOR CALLS Director: Aisling Walsh. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: David Thewlis, Miranda Richardson and Sophie Rundle. BBC / Drama Republic. PARTNERS IN CRIME Director: Ed Hall. Producer: Georgina Lowe. Starring: Jessica Raine, David Walliams, Matthew Steer and Paul Brennen. Endor Productions / Acorn Productions. Gable House, 18 –24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 AMY ROBERTS Contd … 2 CILLA Director: Paul Whittington. Producer: Kwadjo Dajan. Starring: Sheridan Smith, Aneurin Barnard, Ed Stoppard and Melanie Hill. ITV. RTS CRAFT & DESIGN AWARD 2015 – BEST COSTUME DESIGN BAFTA Nomination 2015 – Best Costume Design JAMAICA INN Director: Philippa Lowthorpe Producer: David M. Thompson and Dan Winch. Starring: Jessica Brown Findlay, Shirley Henderson and Matthew McNulty. Origin Pictures. THE TUNNEL Director: Dominik Moll. Producer: Ruth Kenley-Letts. Starring: Stephen Dillane and Clemence Poesy. Kudos. CALL THE MIDWIFE (Series 2) Director: Philippa Lowthorpe.