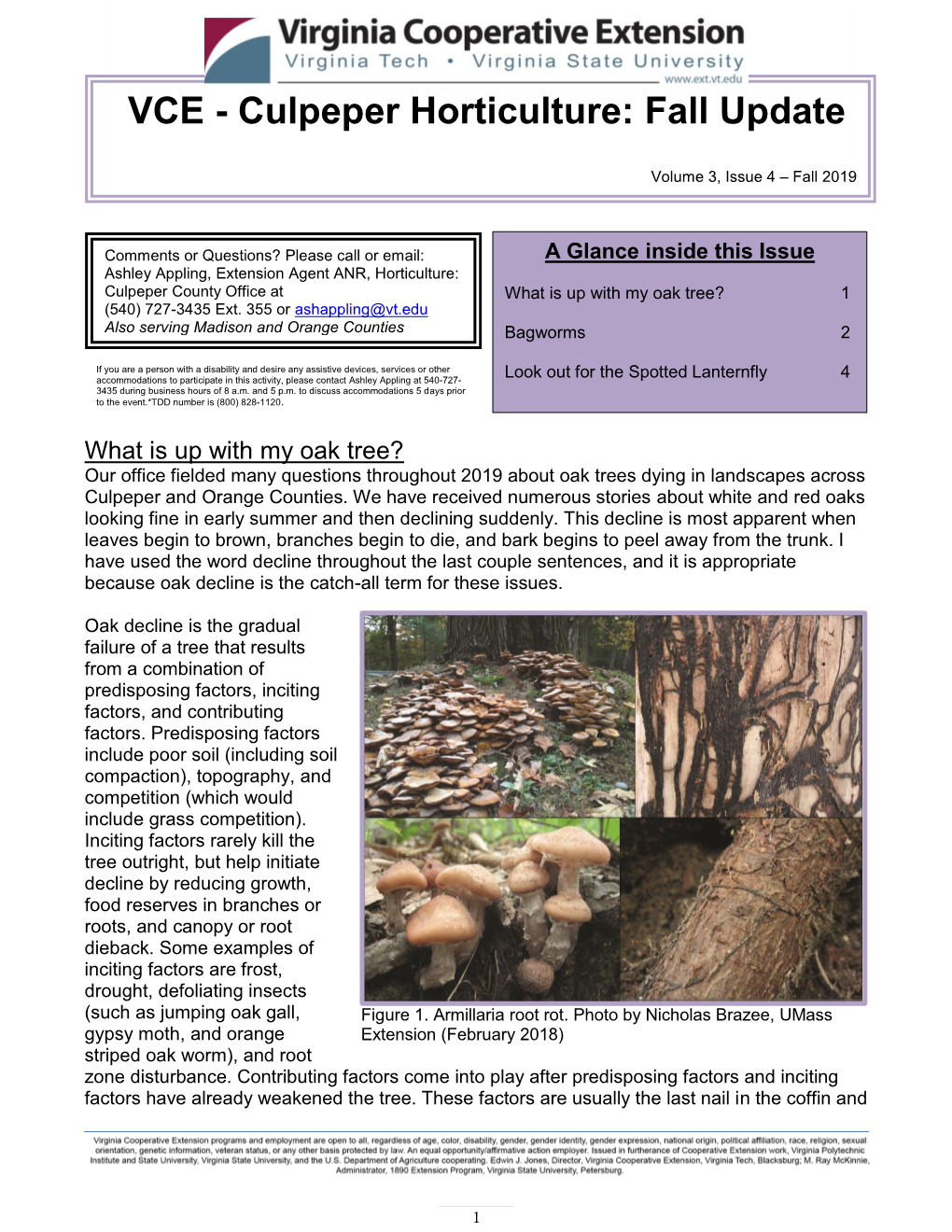

Fall 2019 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bionomics of Bagworms (Lepidoptera: Psychidae)

ANRV363-EN54-11 ARI 27 August 2008 20:44 V I E E W R S I E N C N A D V A Bionomics of Bagworms ∗ (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) Marc Rhainds,1 Donald R. Davis,2 and Peter W. Price3 1Department of Entomology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, 47901; email: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., 20013-7012; email: [email protected] 3Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, 86011-5640; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009. 54:209–26 Key Words The Annual Review of Entomology is online at bottom-up effects, flightlessness, mating failure, parthenogeny, ento.annualreviews.org phylogenetic constraint hypothesis, protogyny This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090448 Abstract Copyright c 2009 by Annual Reviews. The bagworm family (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) includes approximately All rights reserved 1000 species, all of which complete larval development within a self- 0066-4170/09/0107-0209$20.00 enclosing bag. The family is remarkable in that female aptery occurs in ∗The U.S. Government has the right to retain a over half of the known species and within 9 of the 10 currently recog- nonexclusive, royalty-free license in and to any nized subfamilies. In the more derived subfamilies, several life-history copyright covering this paper. traits are associated with eruptive population dynamics, e.g., neoteny of females, high fecundity, dispersal on silken threads, and high level of polyphagy. Other salient features shared by many species include a short embryonic period, developmental synchrony, sexual segrega- tion of pupation sites, short longevity of adults, male-biased sex ratio, sexual dimorphism, protogyny, parthenogenesis, and oviposition in the pupal case. -

Chlorantraniliprole: Reduced-Risk Insecticide for Controlling Insect Pests of Woody Ornamentals with Low Hazard to Bees

242 Redmond and Potter: Acelepryn Control of Horticultural Pests Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 2017. 43(6):242–256 Chlorantraniliprole: Reduced-risk Insecticide for Controlling Insect Pests of Woody Ornamentals with Low Hazard to Bees Carl T. Redmond and Daniel A. Potter Abstract. Landscape professionals need target-selective insecticides for managing insect pests on flowering woody orna- mentals that may be visited by bees and other insect pollinators. Chlorantraniliprole, the first anthranilic diamide insec- ticide registered for use in urban landscapes, selectively targets the receptors that regulate the flow of calcium to control muscle contraction in caterpillars, plant-feeding beetles, and certain other phytophagous insects. Designated a reduced- risk pesticide by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, it has a favorable toxicological and environmental profile, including very low toxicity to bees and most types of predatory and parasitic insects that contribute to pest sup- pression. Chlorantraniliprole has become a mainstay for managing turfgrass pests, but little has been published concern- ing its performance against the pests of woody ornamentals. Researchers evaluated it against pests spanning five different orders: adult Japanese beetles, evergreen bagworm, eastern tent caterpillar, bristly roseslug sawfly, hawthorn lace bug, ole- ander aphid, boxwood psyllid, oak lecanium scale (crawlers), and boxwood leafminer, using real-world exposure scenarios. Chlorantraniliprole’s efficacy, speed of control, and residual activity as a foliar spray for the leaf-chewing pests was as good, or better, than provided by industry standards, but sprays were ineffective against the sucking pests (lace bugs, aphids, or scales). Basal soil drenches in autumn or spring failed to systemically control boxwood psyllids or leafminers, but autumn drenches did suppress roseslug damage and Japanese beetle feeding the following year. -

Butterflies and Moths of Camden County, New Jersey, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Aerial Dispersal and Host Plant Selection by Neonate Thyridopteryx Ephemeraeformis (Lepidoptera: Psychidae)

Ecological Entomology (2004) 29, 327–335 Aerial dispersal and host plant selection by neonate Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) 1 2 ROBERT G. MOORE andLAWRENCE M. HANKS 1United States Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, North, Attention: MCHB-AN Entomological Sciences Division, Maryland and 2Department of Entomology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, U.S.A. Abstract. 1. Neonate evergreen bagworms, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Psychidae), disperse by dropping on a strand of silk, termed silking, and ballooning on the wind. Larvae construct silken bags with fragments of plant foliage. This species is highly polyphagous, feeding on more than 125 species of woody plants of 45 families. The larvae commonly infests juniper (Juniperus spp.) and arborvitae (Thuja spp.), but rarely feed on deciduous hosts such as maples. The hypothesis is proposed that polyphagy in T. ephemer- aeformis is maintained by variation among larvae in dispersal behaviour, and time constraints on the opportunity to disperse, but patterns of host species preference result from a predisposition for larvae to settle on arborvitae and juniper but disperse from other hosts. 2. Consistent with that hypothesis, laboratory experiments revealed: (a) starved larvae varied in their tendency to disperse from paper leaf models; (b) starved larvae readily silked only during their first day; (c) larvae became increasingly sedentary the longer they were exposed to plant foliage; (d) when provided with severalopportunities to silk,larvaebecame sedentary after exposure to arborvitae foliage, but repeatedly silked after exposure to maple (Acer species) foliage or paper; and (e) larvae were less inclined to silk from foliage of arborvitae than from maple. -

Cold Weather in January 2018 May Have Killed Bagworms in Some Parts

Issue: 18-01 February 23, 2018 In This Issue Cold weather in January 2018 may have killed bagworms in some parts of Indiana Take Precautions When Hiring Tree Services to Help with Storm Clean-Up Damping-off of seeds and seedlings Allium ‘Millenium’ Named 2018 Perennial of the Year! Cold weather in January 2018 may have killed bagworms in some parts of Indiana (Cliff Sadof, [email protected]) Although winter weather came late this year, when it finally arrived at the end of December, it was fiercely cold with temperatures dipping well below 0 ˚ F. Most Indiana insects can survive these temperatures. One serious defoliator, the The female lays her eggs inside her body cavity, where they evergreen bagworm may have been killed by the cold weather. remain until they hatch into caterpillars during the following What are bagworms? spring (figure 2 female filled with eggs). Why is cold weather more likely to kill bagworms than other Bagworms, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth) are insects in Indiana? caterpillars that can strip the leaves from a wide variety of trees and shrubs. Evergreen shrubs, like juniper, red cedar, Unlike many insects who insulate themselves from the cold by falsecypress, spruce, arborvitae, fir and pines can be killed when burying below the soil surface, bagworm eggs dangle in bags they lose more than half of their leaves to this pest. Although from branches, well above the soil. Also, they lack the protective deciduous trees like maples, elms, birch, crabapples, willows and mechanisms that many other insects have to protect their tender poplars are more likely to survive when they lose their leaves, tissues from ice crystals that form during the freezing process. -

Forest Health Manual

FOREST HEALTH THREATS TO SOUTH CAROLINA’S FORESTS 1 Photo by Southern Forest Insect Work CONTENTS Conference (Bugwood.org) 3STEM, BRANCH & TRUNK DISEASES 9 ROOT DISEASES 13 VASCULAR DISEASES Forest Health: Threats to South Carolina’s Forests, published by the South Carolina Forestry Commission, August 2016 This forest health manual highlights some of the insect pests and diseases you are likely to encounter BARK-BORING INSECTS in South Carolina’s forests, as well as some threats 18 that are on the horizon. The South Carolina Forestry Commission plans to expand on the manual, as well as adapt it into a portable manual that can be consulted in the field. The SCFC insect and disease staff hopes you find this manual helpful and welcomes any suggestions to improve it. 23 WOOD-BORING INSECTS SCFC Insect & Disease staff David Jenkins Forest Health Program Coordinator Office: (803) 896-8838 Cell: (803) 667-1002 [email protected] 27 DEFOLIATING INSECTS Tyler Greiner Southern Pine Beetle Program Coordinator Office: (803) 896-8830 Cell: (803) 542-0171 [email protected] PIERCING INSECTS Kevin Douglas 34 Forest Technician Office: (803) 896-8862 Cell: (803) 667-1087 [email protected] SEEDLING & TWIG INSECTS 2 35 Photo by Robert L. Anderson (USDA Forest DISEASES Service, Bugwood.org) OF STEMS, BRANCHES & TRUNKS and N. ditissima) invade the wounds and create cankers. BEECH BARK DISEASE Spores are produced in orange-red fruiting bodies that form clusters on the bark. The fruiting bodies mature in the fall Overview and release their spores in moist weather to be dispersed by This disease was first reported in Europe in 1849. -

Forest Health Threats to South Carolina’S Forests

FOREST HEALTH THREATS TO SOUTH CAROLINA’S FORESTS 1 Photo by Southern Forest Insect Work CONTENTS Conference (Bugwood.org) 3STEM, BRANCH & TRUNK DISEASES 9 ROOT DISEASES 13 VASCULAR DISEASES Forest Health: Threats to South Carolina’s Forests, published by the South Carolina Forestry Commission, August 2016 This forest health manual highlights some of the insect pests and diseases you are likely to encounter BARK BORING INSECTS in South Carolina’s forests, as well as some threats 18 that are on the horizon. The South Carolina Forestry Commission plans to expand on the manual, as well as adapt it into a portable manual that can be consulted in the field. The SCFC insect and disease staff hopes you find this manual helpful and welcomes any suggestions to improve it. 23 WOOD BORING INSECTS SCFC Insect & Disease staff David Jenkins Forest Health Program Coordinator Office: (803) 896-8838 Cell: (803) 667-1002 [email protected] 27 DEFOLIATING INSECTS Chisolm Beckham Southern Pine Beetle Program Coordinator Office: (803) 896-6140 Cell: (803) 667-0806 [email protected] PIERCING INSECTS Kevin Douglas 34 Forest Technician Office: (803) 896-8862 Cell: (803) 667-1087 [email protected] SEEDLING & TWIG INSECTS 2 35 Photo by Robert L. Anderson (USDA Forest DISEASES Service, Bugwood.org) OF STEMS, BRANCHES & TRUNKS and N. ditissima) invade the wounds and create cankers. BEECH BARK DISEASE Spores are produced in orange-red fruiting bodies that form clusters on the bark. The fruiting bodies mature in the fall Overview and release their spores in moist weather to be dispersed by This disease was first reported in Europe in 1849. -

United States National Museum Bulletin 244

I^^^^P^MJ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 244 WASHINGTON, D.C. 1964 MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Bagworm Moths of the Western Hemisphere (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) DONALD R. DAVIS Associate Curator of Lepidoptera SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, 1964 Publications of the United States National Museum The scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series are published original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of the Museum and setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of anthropology, biology, geology, history, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the various subjects. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902, papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. This work forms number 244 of the Bulletin series. Frank A. Taylor Director, United States National Museum U.S. -

Avian Predation of the Evergreen Bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae)

11 April 2000 PROC. ENTOMOL. SOC. WASH. 102(2), 2000, pp. 350-352 AVIAN PREDATION OF THE EVERGREEN BAGWORM (LEPIDOPTERA: PSYCHIDAE) ROBERT G. MOORE AND LAWRENCE M. HANKS Department of Entomology, 320 Morrill Hall, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract.-We report for the first time predation of evergreen bagworms, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Psychidae), by English Sparrows, Passer do mesticus (L.). Sparrows were removing bagworm bags from a juniper planting and carried them to sheltered locations. They fed on the larvae by squeezing their bags repeatedly from one end to the other (to squeeze out guts and hemolymph) or by vigorously shaking the bag to eject the larvae. Of 359 bagworm bags that had accumulated on sidewalks and under nearby trees, birds had apparently completely extracted larvae from 62% of the bags and killed another 36% of larvae. Key Words: population regulation, bird behavior, predation, ornamental plants Evergreen bagworm, Thyridopteryx Horn and Sheppard 1979, Gross and Fritz ephemeraeformis (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: 1982, Cronin 1989). The impact of verte Psychidae), is an important pest of woody brate predators on bagworm populations ornamental plants throughout the eastern rarely has been investigated; these include United States, feeding on more than 126 rodents (Cronin 1989) and birds (English plant species (Davis 1964, Johnson and sparrows, blackbirds, tufted titmice, chick Lyon 1988). The primary host plants of adees, and Carolina wrens; Haseman 1912, bagworms are arborvitae (Thuja spp.) and Horn and Sheppard 1979, Summers-Smith juniper (Juniperus spp.) (Johnson and Lyon 1988, Lowther and Cink 1992). -

Caterpillars on the Foliage of Conifers in the Northeastern United States 1 Life Cycles and Food Plants

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Coniferous forests are important features of the North American landscape. In the Northeast, balsam fir, spruces, or even pines may dominate in the more northern forests. Southward, conifers still may be prevalent, although the pines become increasingly important. In dry, sandy areas, such as Cape Cod of Massachusetts and the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, hard pines abound in forests composed of relatively small trees. Conifers are classic symbols of survival in harsh environments. Forests of conifers provide not only beautiful scenery, but also livelihood for people. Coniferous trees are a major source of lumber for the building industry. Their wood can be processed to make paper, packing material, wood chips, fence posts, and other products. Certain conifers are cultivated for landscape plants and, of course, Christmas trees. Trees of coniferous forests also supply shelter or food for many species of vertebrates, invertebrates, and even plants. Insects that call these forests home far outnumber other animals and plants. Because coniferous forests tend to be dominated by one to a few species of trees, they are especially susceptible to injury during outbreaks of insects such as the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana, the fall hemlock looper, Lambdina fiscellaria fiscellaria, or the pitch pine looper, Lambdina pellucidaria. Trees that are defoliated by insects suffer reduced growth and sometimes even death. Trees stressed by defoliation, drought, or mechanical injury, are generally more susceptible to attack by wood-boring beetles, diseases, and other organisms. These secondary pests also may kill trees. Stress or tree death can have a negative economic impact upon forest industries. -

Butterflies and Moths of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail