Church and Community in Bristol During the Sixteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

The Beginnings of English Protestantism

THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH PROTESTANTISM PETER MARSHALL ALEC RYRIE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge ,UK West th Street, New York, -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt. System LATEX ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library hardback paperback Contents List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors x List of abbreviations xi Introduction: Protestantisms and their beginnings Peter Marshall and Alec Ryrie Evangelical conversion in the reign of Henry VIII Peter Marshall The friars in the English Reformation Richard Rex Clement Armstrong and the godly commonwealth: radical religion in early Tudor England Ethan H. Shagan Counting sheep, counting shepherds: the problem of allegiance in the English Reformation Alec Ryrie Sanctified by the believing spouse: women, men and the marital yoke in the early Reformation Susan Wabuda Dissenters from a dissenting Church: the challenge of the Freewillers – Thomas Freeman Printing and the Reformation: the English exception Andrew Pettegree vii viii Contents John Day: master printer of the English Reformation John N. King Night schools, conventicles and churches: continuities and discontinuities in early Protestant ecclesiology Patrick Collinson Index Illustrations Coat of arms of Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk. -

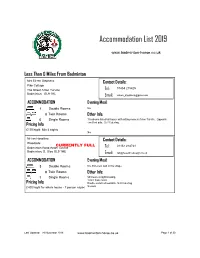

Accommodation List 2019

Accommodation List 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Less Than 0 Miles From Badminton Mrs Eileen Stephens Contact Details: Pike Cottage 01454 218425 The Street Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, GL9 1HL Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 1 Double Rooms No 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 0 Single Rooms 1 bedroom listed toll house with sitting room in Acton Turville. Opposite Pricing Info: excellent pub. Self Catering. £170/night Min 4 nights No Mr Ian Heseltine Contact Details: Woodside CURRENTLY FULL 01454 218734 Badminton Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, S. Glos GL9 1HE Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms No. Excellent pub in the village 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms Minimum 4 night booking. 1 mile from event Pricing Info: Double sofa bed available. Self Catering £400/night for whole house - 7 person capac No pets. ity Last Updated: 29 November 2018 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Page 1 of 30 Ms. Polly Herbert Contact Details: Dairy Cottage 07770 680094 Crosshands Farm Little Sodbury Tel: , South Glos BS37 6RJ Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Optional and by arrangement - pubs nearby Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms 1 double ensuite £140 pn - 1 room with double & 1 - 2 singles ensuite - £230 pn. Other contact numbers: 07787557705, 01454 324729. Minimum Pricing Info: stay 3 nights. Plenty of off road parking. Very quiet locaion. £120 per night for double room inc. breakfas t; "200 per night for 4-person room with full o Transportation Available Less Than 1 Miles From Badminton Mrs Jenny Lomas Contact Details: Five Pines 01454 218423 Sodbury Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, Gloucestershire GL9 1HD Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms No, good pub within walking distance in village Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms 07748 716148. -

John Leland's Itinerary in Wales Edited by Lucy Toulmin Smith 1906

Introduction and cutteth them out of libraries, returning home and putting them abroad as monuments of their own country’. He was unsuccessful, but nevertheless managed to John Leland save much material from St. Augustine’s Abbey at Canterbury. The English antiquary John Leland or Leyland, sometimes referred to as ‘Junior’ to In 1545, after the completion of his tour, he presented an account of his distinguish him from an elder brother also named John, was born in London about achievements and future plans to the King, in the form of an address entitled ‘A New 1506, probably into a Lancashire family.1 He was educated at St. Paul’s school under Year’s Gift’. These included a projected Topography of England, a fifty volume work the noted scholar William Lily, where he enjoyed the patronage of a certain Thomas on the Antiquities and Civil History of Britain, a six volume Survey of the islands Myles. From there he proceeded to Christ’s College, Cambridge where he graduated adjoining Britain (including the Isle of Wight, the Isle of Man and Anglesey) and an B.A. in 1522. Afterwards he studied at All Souls, Oxford, where he met Thomas Caius, engraved map of Britain. He also proposed to publish a full description of all Henry’s and at Paris under Francis Sylvius. Royal Palaces. After entering Holy Orders in 1525, he became tutor to the son of Thomas Howard, Sadly, little or none of this materialised and Leland appears to have dissipated Duke of Norfolk. While so employed, he wrote much elegant Latin poetry in praise of much effort in seeking church advancement and in literary disputes such as that with the Royal Court which may have gained him favour with Henry VIII, for he was Richard Croke, who he claimed had slandered him. -

The Archdeacon's Visitation and Admission of Churchwardens 2021

The Archdeacon’s Visitation and Admission of Churchwardens 2021 Welcome God of power, through your Spirit you promote peace and reconciliation, partnership and encouragement. May the boldness of your Spirit transform us, the gentleness of your Spirit lead us, the gifts of your Spirit equip us, to serve and worship you now and always. Amen. Bible Reading The Archdeacon’s Charge The Archdeacon addresses the Churchwardens Do you believe that God has called you to serve as Churchwarden of your parish? I believe that God has called me. Will you trust in God for strength to fulfil the task to which he has called you? With the help of God, I will. Will you give yourself in love to serve the people of your parish, the members of your congregation and the Bishop of Peterborough? With the help of God, I will. Churchwardens are officers of the Bishop and lay leaders of the parish. Your role, by Canon Law, is to be foremost in representing the laity and in co-operating with the incumbent; by example and precept to encourage parishioners in the practice of true religion; and to promote peace and unity among them. With the help of God, and in collaboration with all the baptised, you are called to holiness of life, to be persons of integrity, recognising your accountability for the tasks entrusted to you. I therefore ask you to make your declaration, before God and his Church. Churchwardens I do solemnly and sincerely declare before God and his people that I will faithfully and diligently discharge the duties of my office as Churchwarden to the parish in which I have been duly elected, calling at all times on the strength that God gives me. -

Study 29 Presentation the Story Also Talks About Five Movements That

Study 29 Presentation The Story also talks about five movements that take part in God’s Story: Movement 1: The Story of the Garden (Genesis 1-11) Movement 2: The Story of Israel (Genesis 12 – Malachi) Movement 3: The Story of Jesus (Matthew – John) Movement 4: The Story of the Church (Acts – Jude) Movement 5: The Story of a New Garden (Revelation) Paul’s Final Days Paul wrote most of the books of the New Testament. Reason for writing – Important to remember that he wrote books to reinforce what he had taught in those places and often to address specific questions that had been raised by the people – sometimes have to work backward to determine the reason for Paul’s responses Word of God – At the same time we recognize that the Bible is the inspired word of God so it speaks to us with timeless truths as well. Three years at Ephesus – Paul stayed there longer than any other place on his journeys; Paul met with the Ephesian elders on his way to Jerusalem at the end of the third missionary journey and wrote to Ephesus during his first imprisonment Ephesus Large and important city – on the coast of Asia Minor 300,000 residents – larger than the capitol, Pergamum Architecture – Community baths, gymnasiums, and impressive buildings, including a huge library Wealthy homes – with frescoed walls Temple of Artemis or Diana – one of the seven wonders of the ancient world Goddess of the hunt, moon, and fertility – temple prostitution and magic Silversmiths – sold images of Diana; big source of revenue Timeless Truth: Suffering and Perseverance are -

The Shield Name the Shield Family in Pamington, Ashchurch

The Shield Name The Shield family have been living in Gloucestershire for at least 500 years. For a large part of that time the name Shield seems to have been interchangeable with the name Shill. The meaning of these names is unclear. In England the name Shield comes either from the occupational name for an armourer from the Middle English scheld meaning a shield, or from the Middle English schele meaning a hut, shed or shelter used by herdsmen as temporary accommodation in summer pastures. The name Shill, which seems to be peculiar to Gloucestershire, is unexplained. In Ireland the name Shield comes from the anglicised form of Ó Siadhail meaning a descendant of Siadhal . The name Shields, with the final ‘s’ is a habitational name for someone coming from North or South Shields in Northern England. The name Shield in Gloucestershire was also found with many alternative spellings. I have come across Shield, Sheild, Sheilde, Shelde, Sheyld, Shelyde, Shild, Shilde, Shyld and Shylde. There are rumours handed down in various branches of the family that the Shield family arrived in Gloucestershire from further north. In one case there is a story that two Shield brothers walked down from Scotland to Bristol. In another, the story is that a Shield farmer drove his cattle down from the north of England to Bristol for sale in the market, started to walk back, stopped in a pub and liked it so much that he used the money from the sale of the cattle to buy the pub and thus remained in Gloucestershire. -

A Reappraisal of the Feast of Fools: Interaction and Reciprocity Between the Clerical and the Secular

A Reappraisal of the Feast of Fools: Interaction and Reciprocity between the Clerical and the Secular A Reappraisal of the Feast of Fools: Interaction and Reciprocity between the Clerical and the Secular MA Thesis History: Europe 1000-1800 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. p.c.m. Peter Hoppenbrouwers Due Date: 31/08/2019 Number of Credits: 20 Number of Words: 18.513 Name: Sokratis Vekris Student Number: 2254379 Address: Vasileiou 8, 15237, Athens, Greece Telephone number: +30 6948078458 E-mail address: [email protected] 1 A Reappraisal of the Feast of Fools: Interaction and Reciprocity between the Clerical and the Secular Table of Contents 1. Introduction p. 3 - 11 2. What Counts as Feast of Fools? p. 12 - 28 2.1. Tracing the Origins p. 12 - 14 2.2. Essential Features p. 14 - 19 2.3. Regional Variations p. 19 - 23 2.4. Contemporary Perception of the “Feast of Fools” p. 24 – 28 3. Lay and Clerical Interaction p. 29 - 48 3.1. Inviting the Laity p. 29 - 37 3.2. Clerical Participation in the Parallel Lay Festivities p. 38 - 48 4. Conclusion p. 49 5. Bibliography p. 50 - 53 2 A Reappraisal of the Feast of Fools: Interaction and Reciprocity between the Clerical and the Secular Introduction At the end of the eleventh century various regions of Northern France witnessed the emergence of what is arguably the most controversial ecclesiastical liturgy in the history of Catholic Christianity: The Feast of Fools. The first surviving notice of the feast comes from a learned theologian of Paris named Joannes Belethus (1135-1182), written in the period between 1160 and 1164. -

Anne Boleyn: Whore Or Martyr?

Muhareb 1 Anne Boleyn: Whore or Martyr? An Individual’s Religious Beliefs Shaping the Perception of the Queen of England By Samia Muhareb Senior Thesis in History California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 9 June 2010 Grade: Advisor: Dr. Amanda Podany Muhareb 2 One of the most famous and influential English queen’s who altered society both politically and religiously was Anne Boleyn. The influence Anne Boleyn had on English society in the sixteenth century was summed up by historian Charles Beem, “our biggest enemy is terrorism…theirs was the Reformation. You can't overestimate how traumatic the changes in the church would have been. You might get close if you imagined that Monica Lewinsky had been a radical Islamist and Bill Clinton married her and made everyone convert.”1 Anne Boleyn was not the typical English Rose;2 she had an intense tempting quality that greatly attracted King Henry VIII. She was said to possess a delicate and attractive appearance, a vivacious personality, and exotic features since she was not brought up in the English court but rather the French to serve Queen Claude of France. To Henry, Anne symbolized the sophistication and charm of the French court he so earnestly desired.3 Anne Boleyn was the second wife of Henry VIII after his divorce from Katherine, a divorce that would revolutionize England as the country broke free from the Catholic Church and established the Church of England. Before King Henry VIII married Katherine of Aragon, Katherine was wedded to his elder brother Arthur in 1501. A year after their marriage, Arthur died; but the cause of death remains unknown. -

Bristol Office Locator

Office Locator KPMG LLP (UK) 66 Queen Square, Bristol BS1 4BE Switchboard: 0117 905 4200 M4 Junction 19 Pupert St Bristol Marriott Perry Rd Visiting or travelling to Bristol Bristol Bierkeller Hotel City Centre A420 Castle Park Park Row Broad St Car Small St A4044 M4 Junction 19, exit onto M32 towards Bristol Colston Hall O2 Academy Bristol Bristol M32 Parkway Continue onto Newfoundland St/A4032 Bristol Hippodrome Baldwin St Old Bread St Theatre Temple Back Continue to follow A4032 The Fleece Slight left onto Temple Way/A4044 Victoria St Continue to follow A4044 King St At the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto TempleWay Bristol Aquarium Temple Gate/A4 Prince St Queen Square At-Bristol Science Centre At the roundabout, take the 4th exit and Welesh Back tS ffilcdeR tS Waterfront Redcliffe Way stay on Temple Gate/A4 The Grove Square Bristol Templetemple Meads Thekla Continue straight onto Redcliffe Way/A4044 Redcliffe Way Temple Gate At the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto St Mary Redcliffe Church River Avon Redcliffe Way M Shed Rd Wapping Guinea St At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto Redcliffe Hill The Grove Somerset St Fowlers of Bristol Commercial Rd Turn right onto Prince St River Avon A370 Turn right onto Middle Ave River Avon Clarence Rd Turn left onto Queen Square Destination will be on the left Source: KPMG LLP (UK) SAT NAV post code is BS1 4JP Rail The nearest station is Bristol Temple Meads, which is a ten minute walk from the office. Parking Parking is only available for Clients www.kpmg.co.uk kpmg.com/uk © 2017 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG Intaernational Cooperative, a Swiss entity. -

The Bristol Medico - Chirurgical Journal

The Bristol Medico - Chirurgical Journal A JOURNAL OF THE MEDICAL SCIENCES FOR THE WEST OF ENGLAND AND SOUTH WALES. PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE BRISTOL MEDICO-CHIRURGICAL SOCIETY. EDITOR : J. A. NIXON, C.M.G., M.D., F.R.C.P. WITH WHOM ARE ASSOCIATED E. W. HEY GROVES, D.Sc., M.S., F.R.C.S. A. E. ILES, O.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.R.C.S. A. RENDLE SHORT, M.D., B.S., B.Sc., F.R.C.S. E. WATSON-WILLIAMS, M.C., Ch.M., F.R.C.S., Assistant Editor. EDITORIAL SECRETARY : A. L. FLEMMING, M.B., Ch.B. "Sctte est ncBclre, nfai (6 mc Sctve alius aciret." VOL. LIV. BRISTOL: J. W. ARROWSMITH LTD. London : J. W. Arrowsmith (London) Ltd. Contents of Vol. LIV Page The Evolution of a Casualty Clearing Station on the Western Front. By Richard C. Clarke, O.B.E., M.B., F.R.C.P. .. 1 ^lie Enlarged Prostate from the point of view of Practitioner and Surgeon. By C. Ferrier Walters, F.R.C.S. .. 21 J-lie Therapeutic Value of Altitude. By Bernard Hudson, M.D., M.R.C.P 35 -The Role of the Central Nervous System in Disease : Recent Experi- mental Work in the U.S.S.R. By F. Bodman, M.D. 41 ^he Carey Coombs Memorial Lecture on the Pathology and Surgical Treatment of Cardiac Ischsemia. By Laurence O'Shaughnessy, F.R.C.S 109 S?m.e Reflections on Research in Medicine. By F. J. Poynton, M.D., F.R.C.P 127 Spinal Anaesthesia. -

515 Bus Service Valid from January 2019

.travelwest.info www BD11449 DesignedandprintedonsustainablysourcedmaterialbyBristolDesign,CityCouncil–January2019 on 0117 922 2910 922 0117 on CD-ROM or plain text please contact Bristol City Council Council City Bristol contact please text plain or CD-ROM Braille, audio tape, large print, easy English, BSL video, video, BSL English, easy print, large tape, audio Braille, If you would like this information in another language, language, another in information this like would you If Hartcliffe – Imperial Park Imperial – Hartcliffe Whitchurch – Hengrove Park – Park Hengrove – Whitchurch Stockwood – Hengrove – Hengrove – Stockwood Valid from January 2019 January from Valid Bus Service Bus 515 www.travelwest.info/bus other bus services in Bristol is available at: available is Bristol in services bus other Timetable, route and fares information for service 515 and and 515 service for information fares and route Timetable, Produced by Sustainable Transport. Sustainable by Produced www.bristolcommunitytransport.org.uk w: [email protected] e: contract by Bristol Community Transport. Community Bristol by contract 0117 941 3713 941 0117 t: under operated is and Council City Bristol please contact Bristol Community Transport: Community Bristol contact please Service 515 is financially supported by by supported financially is 515 Service enquiries property lost and information fares For 0 37 A SS PA holidays. public [email protected] Y e: B N O ST except Saturday to Monday operates service The A 2910 922 0117 t: G N LO Information