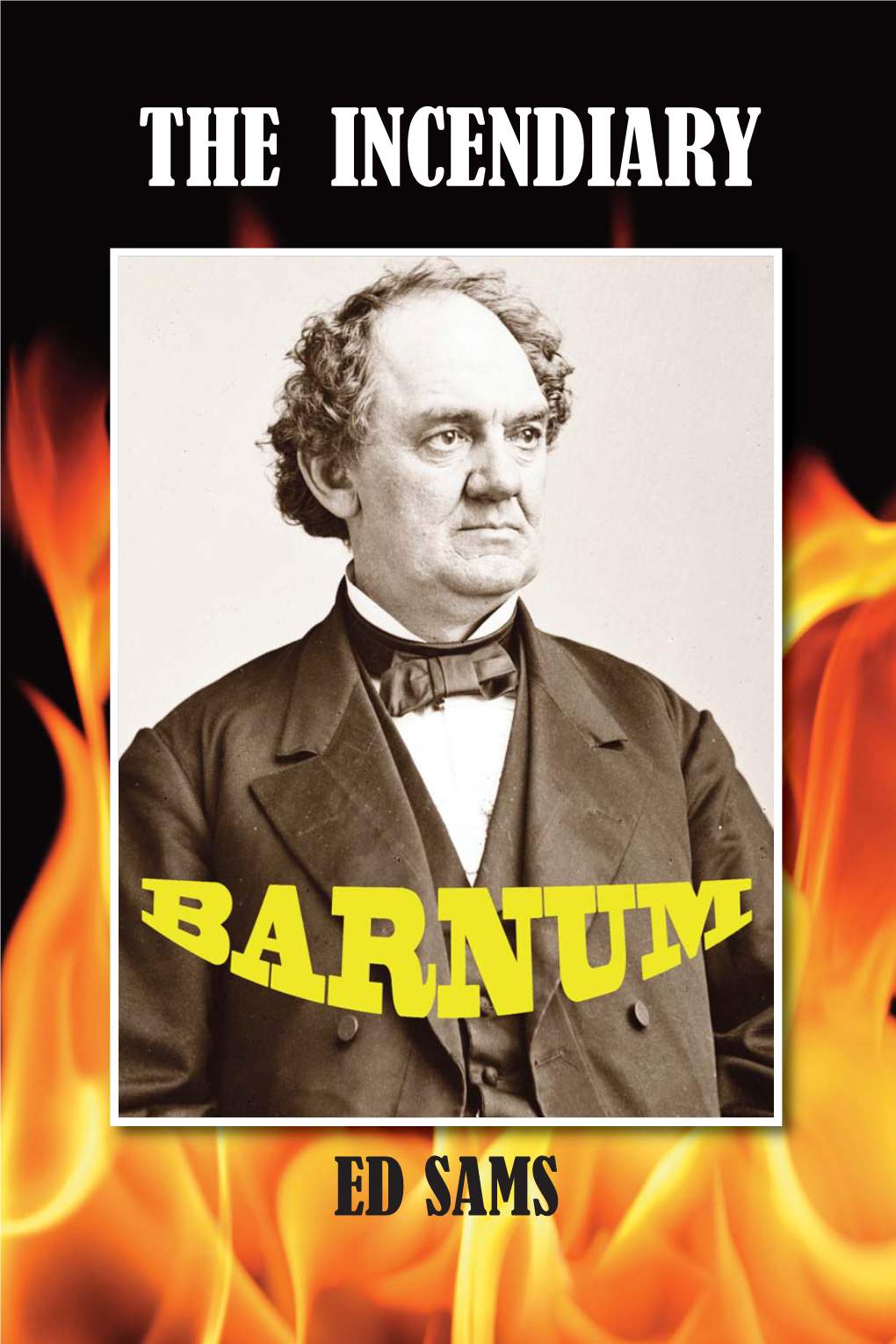

The Incendiary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Description of Metaphor Found in the Greatest Showman's Selected Songs a Paper Written by Sabda Nabila Simanjuntak Reg.No 16

A DESCRIPTION OF METAPHOR FOUND IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN’S SELECTED SONGS A PAPER WRITTEN BY SABDA NABILA SIMANJUNTAK REG.NO 162202034 DIPLOMA-III ENGLISH STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am, SABDA NABILA SIMANJUNTAK, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where the reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no Material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualifield for or awarded another degree.No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the maintext Of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of anotherdegree in any tertiary education. Signed : Date : i Universitas Sumatera Utara COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name : SABDA NABILA SIMANJUNTAK Title of Paper : A DESCRIPTION OF METAPORS FOUND IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN‟S SELECTED SONGS Qualification : D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Librarian of the Diploma III English Department Faculty Of culture Studies USU on understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. Signed : Date : ii Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRACT This paper is entiled “A Description of Metaphors Found in The Greatest Showman's Song” lyrics discusses the types and meanings of metaphors in the lyrics of songs from the greatest showman film. In this paper the author writes a paper using descriptive methods, collecting several data from several books, and the internet. -

Barnum Museum, Planning to Digitize the Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/humanities-collections-and-reference- resources for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for "The Greatest Digitization Project on Earth" with the P. T. Barnum Collections of The Barnum Museum Foundation Institution: Barnum Museum Project Director: Adrienne Saint Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Barnum Museum Foundation, Inc. Application to the NEH/Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Program Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

Barnum Institute of Science and History" in Low Relief

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) &ifiif *y tfvtft. pillllii^ COMMON: r^<~~~~ r. , ~T~~~^ Barnum Museum /" ^, -v/\ AND/OR HISTORIC: /fc fttffiNftJ "'^ Barnum. .Institute of s.$-ienp,<? a.nr) History iffifoxv STREET AND NUMBER: ICO'. \ P Rn^ MATTI Street CITY OR TOWN: X%; ^^\^' Brido-fipnrt STATE CODE COUNTY: ^^J 1 I'f'^ \-^ CODE Connecti cut DQ T?n la^isld,,,.,.....,,,,............,. , ,,,,001...... li!l|$pli;!!iieil::!!::!!l!;;! STATUS ACCESSIBLE <c"«o™ ™«t™" TO THE PUBLIC G District 22 Building El Public Public Acquisition: BQ Occupied Yes: ,, . El Restricted G Site G Structure d Private G In Process D Unoccupied *Qsl i in . G Unrestricted G Object D Botn D Being Considerec G Preservation work in progress ' ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) G Agricultural G Government G Park 1 | Transportation 1 1 Comments G Commercial G Industrial G Private Residence n Other (Soecify) G Educational G Military G Religious 1 I Entertainment 53 Museum | | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: STATE: City of Bridgeport STREET AND NUMBER: Connecticut CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE: CODE ill .....Bridgeport C onnecticut O<9 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: Citv Hal 1 STREET AND NUMBER: ^airfield It 1} T.yon Terrace CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE CODE Rridsre-nort p..7T)7iftCtPiffiTh OQ llltl!!!!^ TITUE OF SURVEY: a NUMBERENTRY Connecticut Historic Structures and Landmarks Survey Tl DATE OF SURVEY: -| Q££ r~j Federal Qfl State "G County G L°ca O 73 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Z TO CO CO Connecticut. -

Empire State Building and Twentieth Century Fox

EMPIRE STATE BUILDING AND TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX DEBUT NEW MUSIC-TO-LIGHT SHOW First ever light show to be synced to a live performance from star of “The Greatest Showman” debuts on December 9, 2017 New York, NY (December 8, 2017) – Empire State Realty Trust, Inc. (NYSE: ESRT) today announced that the Empire State Building will present a music-to-light show choreographed to “This is Me” penned by Academy and Tony Award-winning songwriting duo Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (“La La Land,” “Dear Evan Hansen”) from the upcoming feature film “The Greatest Showman.” The brand-new show designed by renowned lighting designer Marc Brickman will premiere at 8:30 p.m. EST on Saturday, December 9, 2017, during a private reception with jaw-dropping views of the Empire State Building as its spectacular backdrop. Actress Keala Settle, who performs the song in the film as The Bearded Lady, will sing “This is Me” live while the world-famous Empire State Building illuminates New York City around her. The performance will be live-streamed on the Empire State Building’s Facebook Page and social media platforms. A video of the entire show will be posted on the Empire State Building’s YouTube channel (www.youtube.com/esbnyc) immediately following the event. “The Greatest Showman” tells a classic New York story about innovation and ingenuity, traits that exemplify the Empire State Building,” said Anthony E. Malkin, Chairman, and CEO of ESRT. “This is Me,” performed by powerhouse vocalist Keala, is the perfect anthem to celebrate the film and the transcendent nature of the iconic Empire State Building.” “The Greatest Showman” is a bold and original musical that celebrates the birth of show business and the sense of wonder we feel when dreams come to life. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Bone Man to Perform at Brits Ag ‘N’ Bone Man Is Set to Perform at This Year’S BRIT Awards

Established 1961 29 Lifestyle Gossip Sunday, January 14, 2018 Rag ‘N’ Bone Man to perform at BRITs ag ‘N’ Bone Man is set to perform at this year’s BRIT Awards. The ‘Human’ has so far spent over 47 weeks in the UK charts. BRITs Chairman & CEO and hitmaker - who picked up the Critics’ Choice and British Breakthrough Chairman of Sony Music UK & Ireland Jason Iley said: “Rory epitomizes how Rgong at last year’s ceremony - has been asked to hit the stage at the music dreams can come true. He has had the most amazing 12 months and I’m so extravaganza, held at The O2 Arena on February 21, for a killer performance. delighted to see him back where it all started.” The Mastercard-sponsored cere- Taking to his Twitter account on Saturday he said: “Jheez! 2017 has flown by mony will see British comedian Jack Whitehall host. Meanwhile, yesterday the super quick. Its pretty mental to think that I bagged 2 awards at the @Brits last awards will kick off with the nominations launch show, ‘The BRITs Are Coming year and now I’m heading back to perform #brits (sic)” The 32-year-old singer - 2018’, which will once again be hosted by Emma Willis, and will air on UK TV whose real name is Rory Charles Graham - will join the likes of Ed Sheeran, Sam channel ITV from 5.45pm. Liam Payne, Jorja Smith, Paloma Faith, Clean Bandit Smith, Stormzy and Foo Fighters who are also performing. The ‘Skin’ hitmaker has and J Hus will perform. -

Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge

BOOK SUMMARY She built a monument for all time. Then she was lost in its shadow. Discover the fascinating woman who helped design and construct an American icon, perfect for readers of The Other Einstein. Emily Warren Roebling refuses to live conventionally―she knows who she is and what she wants, and she's determined to make change. But then her husband Wash asks the unthinkable: give up her dreams to make his possible. Emily's fight for women's suffrage is put on hold, and her life transformed when Wash, the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, is injured on the job. Untrained for the task, but under his guidance, she assumes his role, despite stern resistance and overwhelming obstacles. Lines blur as Wash's vision becomes her own, and when he is unable to return to the job, Emily is consumed by it. But as the project takes shape under Emily's direction, she wonders whose legacy she is building―hers, or her husband's. As the monument rises, Emily's marriage, principles, and identity threaten to collapse. When the bridge finally stands finished, will she recognize the woman who built it? Based on the true story of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Engineer's Wife delivers an emotional portrait of a woman transformed by a project of unfathomable scale, which takes her into the bowels of the East River, suffragette riots, the halls of Manhattan's elite, and the heady, freewheeling temptations of P.T. Barnum. It's the story of a husband and wife determined to build something that lasts―even at the risk of losing each other. -

The Greatest Showman

Movies & Languages 2018-2019 The Greatest Showman About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR Michael Gracey YEAR/COUNTRY 2017 / USA GENRE Musical film ACTORS Hugh Jackman, Zac Efron, Michelle Williams, Rebecca Ferguson and Zendaya PLOT Set in the second half of the mid-ninteenth century, the story tells, on the one hand, of a romance between Phineas T. Barnum, a poor tailor’s son, and Charity Hallett, a rich businessman’s daughter. Despite the objection of Charity’s parents, Phineas and her get married and have two daughters. Living in a very humble way, they are at first happy. Barnum, however, craves to be successful and to give his family more. He consequently starts up a circus. Although at first he is not successful, he changes approach and the business begins to grow. Part of his new approach is to include people who are not exactly normal, like dwarves or bearded ladies. This new more freakish angle of his circus begins to attract more people. His ride to success is a bit bumpy at first, but in the end he and his family become fabulously rich and are accepted in New York society. P. T. Barnum is still known as the most circus that ever existed. LANGUAGE The language is sensational. This is a film about success and fulfilling dreams, and the language often reflects both. VOCABULARY To wish: there are three ways to use this verb: Blue prints: the plans/drawings for how to build “I wish I had a Million dollars” (impossibility); “I something wish you would study” (possibility); “I wished upon a star” or “I made a wish” Substantial collateral: to put a lot of money as Freaks: people or things that are not normal an initial payment toward paying for something Flotilla of sailing vessels: a fleet of boats/ships Trapeeze: ropes with a bar attached to them, that men hold on to while they fly about the sky and do acrobatics Something that isn’t stuffed: something that To rub my parents noses in success: when you isn’t filled with something. -

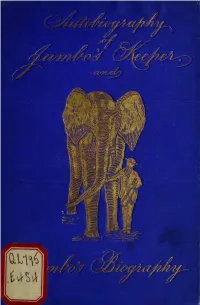

Autobiography of Matthew Scott, Jumbo's Keeper ... : Also Jumbo's

}tm v.> (IL^o^.fcj^ J '5. r & 3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofmOOscot ) MEDAL PRESENTED BY THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LON- DON "TO MATTHEW SCOTT, FOR HIS SUCCESS IX BREED- ING FOREIGN ANIMALS IN THE SOCIETY'S GARDENS, 1866." {Side representing Kingdom of Beasts. representing Kingdom of Birds.) AUTOBIOGRAPHY MATTHEW SCOTT JUMBOS KEEPER FORMERLY OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY'S GABDENS, LONDON, AND RECEIVER OF SIR EDWIN LANDSEER MEDAL IN 1866 ALSO JUMBO'S BIOGRAPHY By the Same Author BRIDGEPORT, CONN. TROWS PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING CO., NEW YORK 1885 Q,Un< COPYRIGHT, 1885, BY MATTHEW SCOTT AND THOMAS E. LOWE Bridgeport, Conn. DEDICATION. I take great pleasure in dedicating this book, containing my autobiography and the biography of Junibo, to the people of the United States of America and Great Britain. I have travelled through the United States, North, East, South, and West, and have received in my travels the greatest kindness. If " Jumbo " could but speak, I know he would endorse what I say here. I have had the same experience in Great Britain, and the spirit of gratitude impels me to acknowledge my appreciation of the good will of the people of both countries, b DEDICATION. by dedicating my humble efforts to them, hoping that this attempt may be received with the same kindness that has been always extended to me in person. Respectfully, Matthew Scott. Bridgeport, Conn., January 14, 1885. MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY. CHAPTER I MY BIRTH-PLACE AND START IN LIFE. I purpose giving to the world, for the benefit of my fellow-men, my humble and truthful history. -

"The Greatest Showman on Earth"

"THE GREATEST SHOWMAN ON EARTH" Written by Jenny Bicks Revisions by Jordan Roberts Bill Condon Jonathan Tropper Current Revisions by: M.A. April 20th, 2015 Draft The Greatest Showman On Earth 4/20/15 Draft 1. 1-3 OMITTED 1-3 A strummed BANJO begins... A BASS DRUM joins, beating time. 4 INT. CIRCUS TENT - NIGHT 4 Absolute darkness. Then, a single narrow spotlight goes on, revealing a RINGMASTER, with top hat, his back to us, alone. With his head bowed, the top hat casts his face in shadow. As the MUSIC picks up, he sings in a hushed, dramatic voice: RINGMASTER [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] QUICK CUTS -- CLOSE UPS of the RINGMASTER, seen from behind, in fast-passing shots. The iconic top hat; the cane; red swallowtail coat; shiny black boots; sawdust... RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster (from behind) looks upward. Another spotlight goes on. Way up high in the darkness, a beautiful African- American aerialist, ANNE WHEELER, is spinning on a rope. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster looks the other way -- a new spotlight hits a beautiful TIGHTROPE WALKER, way up high, seemingly walking on air through the vast darkness. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] A cannon FIRES -- sending a HUMAN CANNONBALL flying through the darkness, spotlight following, til he lands in a netting. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster turns, into the light. It is P.T. BARNUM. Handsome. Confident. Exuberant. At the height of his powers. A showman’s smile; a scoundrel’s wink. BARNUM [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] * (CONTINUED) The Greatest Showman On Earth 4/20/15 Draft 2. -

Barnum and the “Barnum” Effect 1

Running head: BARNUM AND THE “BARNUM” EFFECT 1 Barnum and The “Barnum” Effect Jamey Sweet Trinity Western University BARNUM AND THE “BARNUM” EFFECT 2 Barnum and The “Barnum” Effect Intro Peanut shells. Elephants. Colorful Tents. Acrobatics and death-defying acts. Have I got your attention yet? Bearded women. Mermaids. Tiny people and beautiful voices. Doesn’t this sound spectacular? It also sounds like the circus, a place of entertainment and showmanship. While there have been many players that participated in the birth and the growth of the circus, there haven’t been many who became such a world-wide personality as Phineas Taylor Barnum. Men such as Philip Astley birthed the circus with equestrian shows in the 18th century, but in the 19th century as Barnum began traveling under the colorful tent, the circus evolved with the addition of the Sideshow. While PT Barnum is largely associated with the circus, a wider look on his life can reveal business talent, especially in the entertainment industry. Barnum had used advertising and marketing to his advantage like no one else before him, and yet still proclaimed to hold to some of the business ethics of previous century. His pride and glory, other than his family, was the American Museum, which was an exhibition of oddities, curiosities, and sensations, some of them being human exhibits. This foundation provided a launchpad into the circus industry. Who was Phineas Taylor Barnum? Why was he so “successful” in his field? What are his drives, motivations, and passions that got him up in the morning? Was he happy? What happened in Barnum’s failures in life and how did they affect him? As we explore the biggest personality of the 19th century, we may uncover that this self-proclaimed “Humbug” has a personality that is hard to pin down among all of his personas.