Maryland Historical Magazine, 1996, Volume 91, Issue No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1997, Volume 92, Issue No. 2

i f of 5^1- 1-3^-7 Summer 1997 MARYLAND Historical Magazine TU THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY Founded 1844 Dennis A. Fiori, Director The Maryland Historical Magazine Robert I. Cottom, Editor Patricia Dockman Anderson, Associate Editor Donna B. Shear, Managing Editor Jeff Goldman, Photographer Angela Anthony, Robin Donaldson Coblentz, Christopher T.George, Jane Gushing Lange, and Robert W. Schoeberlein, Editorial Associates Regional Editors John B. Wiseman, Frostburg State University Jane G. Sween, Montgomery Gounty Historical Society Pegram Johnson III, Accoceek, Maryland Acting as an editorial board, the Publications Committee of the Maryland Historical Society oversees and supports the magazine staff. Members of the committee are: John W. Mitchell, Upper Marlboro; Trustee/Ghair Jean H. Baker, Goucher Gollege James H. Bready, Baltimore Sun Robert J. Brugger, The Johns Hopkins University Press Lois Green Garr, St. Mary's Gity Gommission Toby L. Ditz, The Johns Hopkins University Dennis A. Fiori, Maryland Historical Society, ex-officio David G. Fogle, University of Maryland Jack G. Goellner, Baltimore Averil Kadis, Enoch Pratt Free Library Roland G. McGonnell, Morgan State University Norvell E. Miller III, Baltimore Richard Striner, Washington Gollege John G. Van Osdell, Towson State University Alan R. Walden, WBAL, Baltimore Brian Weese, Bibelot, Inc., Pikesville Members Emeritus John Higham, The Johns Hopkins University Samuel Hopkins, Baltimore Gharles McG. Mathias, Ghevy Ghase The views and conclusions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors. The editors are responsible for the decision to make them public. ISSN 0025-4258 © 1997 by the Maryland Historical Society. Published as a benefit of membership in the Maryland Historical Society in March, June, September, and December. -

The Confession of George Atzerodt

The Confession of George Atzerodt Full Transcript (below) with Introduction George Atzerodt was a homeless German immigrant who performed errands for the actor, John Wilkes Booth, while also odd-jobbing around Southern Maryland. He had been arrested on April 20, 1865, six days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had another errand boy, a simpleton named David Herold, who resided in town. Herold and Atzerodt ran errands for Booth, such as tending horses, delivering messages, and fetching supplies. Both were known for running their mouths, and Atzerodt was known for drinking. Four weeks before the assassination, Booth had intentions to kidnap President Lincoln, but when his kidnapping accomplices learned how ridiculous his plan was, they abandoned him and returned to their homes in the Baltimore area. On the day of the assassination the only persons remaining in D.C. who had any connection to the kidnapping plot were Booth's errand boys, George Atzerodt and David Herold, plus one of the key collaborators with Booth, James Donaldson. After David Herold had been arrested, he confessed to Judge Advocate John Bingham on April 27 that Booth and his associates had intended to kill not only Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, but Vice President Andrew Johnson as well. David Herold stated Booth told him there were 35 people in Washington colluding in the assassination. This information Herold learned from Booth while accompanying him on his flight after the assassination. In Atzerodt's confession, this band of assassins was described as a crowd from New York. -

Tenth Regiment

177th Regiment Infantry "10th New York National Guard" In the Civil War THE 177th NEW YORK VOLUNTEER INFANTRY (Tenth Regiment) IN THE WAR FOR THE UNION 1862 - 1863 COMPILED BY COL Michael J. Stenzel Bn Cdr 210th Armor March 1992 - September 1993 Historian 210th Armor Association 177th Regiment Infantry "10th New York National Guard" In the Civil War Organized at Albany, N.Y., Organized 29 December 1860 in the New York State Militia from new and existing companies at Albany as the 10th Regiment. The 10th had offered its services three times and had been declined. While waiting to be called more than 200 members were assigned as officers to other Regiments. 21 September 1862 - Colonel Ainsworth received orders to recruit his regiment up to full war strength. 21 November - with its ranks filled, the 10th was mustered into Federal service as the 177th New York Volunteer Infantry. There were ten companies in the regiment and with the exception of a few men who came from Schenectady all were residents of Albany County. All the members of Companies A, D, E and F lived in Albany City. Company B had eleven men from out of town, Company G had 46, Company H had 31 and Company I had 17. The Company officers were: Company A-Captain Lionel U. Lennox; Lieutenants Charles H. Raymond and D. L. Miller - 84 men. Company B - Captain Charles E. Davis; Lieutenants Edward H. Merrihew and William H. Brainard - 84 men. Company C - Captain Stephen Bronk; Lieutenants W. H. H. Lintner and A. H. Bronson - 106 men. -

Perpetuating the Architecture of Separation: an Analysis of the Presentation of History and the Past at the Riversdale House Museum in Riverdale Park, Maryland

Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 10 Article 15 2019 Perpetuating the Architecture of Separation: An Analysis of the Presentation of History and the Past at the Riversdale House Museum in Riverdale Park, Maryland Ann S. Eberwein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes Recommended Citation Eberwein, Ann S. (2019) "Perpetuating the Architecture of Separation: An Analysis of the Presentation of History and the Past at the Riversdale House Museum in Riverdale Park, Maryland," Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology: Vol. 10 , Article 15. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes/vol10/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Perpetuating the Architecture of Separation: An Analysis of the Presentation of History at Riversdale House Museum in Riverdale Park, Maryland Ann S. Eberwein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA Abstract: Riversdale House Museum is one of many historic houses in the United States with difficult histories, which curators avoid rather than confront. This evasive tactic goes against recent developments in museological method and theory that advocate for social justice as one of a museum’s primary goals. Exhibits at Riversdale focus on architectural restoration and avoid an overt discussion of many aspects of history unrelated to aesthetics. The presentation of history at this site, in the context of a diverse com- munity, is also at odds with recently developed interpretation methods at historic houses that emphasize connection with a mu- seum’s community and audience. -

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River North Fork Watershed Project/Friends of Blackwater MAY 2009 This report was made possible by a generous donation from the MARPAT Foundation. DRAFT 2 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 TABLE OF Figures ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 THE UPPER NORTH BRANCH POTOMAC RIVER WATERSHED ................................................................................... 7 PART I ‐ General Information about the North Branch Potomac Watershed ........................................................... 8 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Geography and Geology of the Watershed Area ................................................................................................. 9 Demographics .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Land Use ............................................................................................................................................................ -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

Charles Benedict Calvert Research Guide

Photoprint of Charles Benedict Calvert by Matthew Brady. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. LC-DIG-cwpbh-03464 Charles Benedict Calvert Research Guide Archives and Manuscripts Department University of Maryland Libraries For more information contact Anne Turkos [email protected] (301) 405-9058 1 CHARLES BENEDICT CALVERT RESEARCH GUIDE Introduction and Biography Charles Benedict Calvert, descendant of the first Lord Baltimore, is generally considered the primary force behind the founding of the Maryland Agricultural College. Chartered in 1856, the College was the forerunner of today’s University of Maryland, College Park. For over twenty-five years, Calvert articulated a strong vision of agricultural education throughout the state of Maryland and acted in innumerable ways to make his vision a reality. He and his brother, George H. Calvert, sold the land that formed the core of the College Park campus for $20,000, half its original cost, and lent the college half of the purchase price. He was elected as the first Chairman of the Board of Trustees, held the second largest number of subscriptions to charter the college, chaired a committee to plan the first buildings, laid the cornerstone for the “Barracks,” stepped in to serve as president of the college when the first president had to resign, and underwrote college expenses when there was no money to pay salaries. Born on August 23, 1808, Charles Benedict was the fifth child of George Calvert and Rosalie Stier Calvert. He was educated at Bladensburg Academy, attended boarding school in Philadelphia, and spent two years in study at the University of Virginia. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

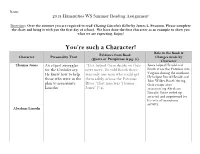

You're Such a Character!

Name:_____________________________________________ 2018 Humanities WS Summer Reading Assignment Directions: Over the summer you are required to read Chasing Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Please complete the chart and bring it with you the first day of school. We have done the first character as an example to show you what we are expecting. Enjoy! You’re such a Character! Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Thomas Jones An expert smuggler “Cox helped them decide on their Jones helped Herold and for the Confederacy. next move. He told Booth there Booth cross the Potomac into He knew how to help was only one man who could get Virginia during the manhunt. those who were in the them safely across the Potomac He helped David Herold and John Wilkes Booth during plan to assassinate River. That man was Thomas their escape after Lincoln. Jones” (74). assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Jones ended up arrested and imprisoned for his acts of treasonous activity. Abraham Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Wilkes Booth Edwin Stanton George Atzerodt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Garrett John Surratt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Mary Surratt Mary Todd Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. -

Historic Alexandria Quarterly

Historic Alexandria Quarterly Winter 2003 ‘For the People’: Clothing Production and Maintenance at Rose Hill Plantation, Cecil County, Maryland Gloria Seaman Allen, Ph.D. Textile production was central to the economic life and While the General supervised the hired hands and arti- daily well being of many large plantations in the Chesa- sans and contributed to the entertainment of their guests, peake region during the early antebellum period. Nu- it was Martha Forman who had the ultimate responsi- merous steps were required to produce cloth and cloth- bility for their provisioning and maintenance—much ing for families on plantations where the enslaved num- of which involved textile work. Her series of diaries bered fifty or more. These steps included cultivation provides important insights into the complexity of the and harvesting of raw materials, fiber preparation, spin- cloth making process, the centrality of cloth and cloth- ning, dyeing, knitting or weaving, fulling or bleach- ing to the plantation economy, and the almost continu- ing, cutting and sewing plain and fine clothing, mend- ous employment of bound and free labor in plantation ing, and textile maintenance. textile production and maintenance. Between 1814 and 1845 Martha Forman, mistress of Raw Materials and Fiber Preparation Rose Hill in Cecil County, on Maryland’s upper East- General Thomas Marsh Forman raised sheep and grew ern Shore, kept daily records of the plantation activi- flax at his Rose Hill plantation.3 He also grew a small ties that came within her sphere of management.1 She amount of cotton and experimented briefly, but unsuc- began a diary on the cessfully, with sericulture or the production of raw silk day of her marriage by raising silk worms. -

The Texas Union Herald Colonel E

The Texas Union Herald Colonel E. E. Ellsworth Camp #18 Department of Texas Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Volume iv Number 5 May 2019 After my grandfather died, and my grandmother Rattling Sabres moved into the city, the picnic was usually held at my by parent’s house because we had a very large yard. Glen E. Zook My mother-in-law, who lived in Atlanta, Georgia, didn’t recognize any need for Memorial Day. However, my Camp #18 has finally “arrived”! In case someone wife, and I, starting the Memorial Day before we got married has not received the latest copy of “The Banner”, the front in June, acquired some flowers. Then, we took her out to cover photograph shows the efforts of Camp #18 members the cemetery where her husband was buried (he had died to clean the tombstones, and memorials, of Civil War when my wife was 9-years old) and put the flowers on his veterans in the various cemeteries around this area. grave. She did appreciate this and asked us the next year Of course, May contains Memorial Day and there to do the same. Then, my wife, and I, moved to Texas. are usually ceremonies, especially in McKinney, recognizing However, my mother-in-law had one of her other daughters the holiday. Camp members always take part in these follow up for several years thereafter. ceremonies and I expect this will continue for 2019. My mother’s family really didn’t celebrate Memorial Although General Order #11 established “Memorial Day that much. -

January 7, 1897

PORTLAND DAILY THREE CLNiS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23. 1862-VOL. 34. PORTLAND. MAINE. THURSDAY MORNING. JANUARY 7. 1887. _PRICE tha of the of Maine. effect of every branch of subject sirable productions, Mr. Loud said the the best interests people he constantly on the alert to full effect of its operations would not Wo mast be prudent and economical and touched upon, THE LOL'D BILL PASSED. Into the path felt lor four years, working so gradually never that the motto of our State proceed xnoro extensively with- forget;; ns not to produce injurious effects success and shrewdly tak- is an umiiitious one.” thut promised out due warning. in cheer- of but forcibly Mr. Kepublican of Missouri, Speaker Larrabee continued a ing advantage gracefully Tracey, of tha moved to amoud the first section of the ful but earnest manner to express It ns complimenting the several parts said rival can- r bill which amendment Mr. Loud Caucus Nominees of'Both Houses his opinion that the members of tire state, especially those having The Measure Has a Good Majorit; would destroy the effect of tho section. |H|H| would be able to serve the didates in the field. Mr. Simpkins, of Massa- House people Kepublican With of anxiety concerning in the chusetts, asked Mr. Loud if the hill in Elected. iu tho most honorable manner and closed expressions House. in- members list- any way teuded to interfere with or his remarks by again thanking them for Water ville Man Will Be the approaching climax, » and was tolu that the jure newspapers, his election.