Post-Separation Conflict and the Use of Family Violence Orders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winterwinter June10june10 OL.Inddol.Indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents |

BBarNewsarNews WinterWinter JJune10une10 OL.inddOL.indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents | 2 Editor’s note 4 President’s column 6 Letters to the editor 8 Bar Practice Course 01/10 9 Opinion A review of the Senior Counsel Protocol Ego and ethics Increase the retirement age for federal judges 102 Addresses 132 Obituaries 22 Recent developments The 2010 Sir Maurice Byers Address Glenn Whitehead 42 Features Internationalisation of domestic law Bernard Sharpe Judicial biography: one plant but Frank McAlary QC several varieties 115 Muse The Hon Jeff Shaw QC Rake Sir George Rich Stephen Stewart Chris Egan A really rotten judge: Justice James 117 Personalia Clark McReynolds Roger Quinn Chief Justice Patrick Keane The Hon Bill Fisher AO QC 74 Legal history Commodore Slattery 147 Bullfry A creature of momentary panic 120 Bench & Bar Dinner 2010 150 Book reviews 85 Practice 122 Appointments Preparing and arguing an appeal The Hon Justice Pembroke 158 Crossword by Rapunzel The Hon Justice Ball The Federal Magistrates Court 159 Bar sports turns 10 The Hon Justice Nicholas The Lady Bradman Cup The Hon Justice Yates Life on the bench in Papua New The Great Bar Boat Race Guinea The Hon Justice Katzmann The Hon Justice Craig barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2010 Bar News Editorial Committee ISSN 0817-0002 Andrew Bell SC (editor) Views expressed by contributors to (c) 2010 New South Wales Bar Association Keith Chapple SC This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted Bar News are not necessarily those of under the Copyright Act 1968, and subsequent Mark Speakman SC the New South Wales Bar Association. -

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler* I The essential elements of the decision-making process of a court are well understood and can be simply stated. The court finds the facts. The court ascertains the law. The court applies the law to the facts to decide the case. The distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law corresponds to the distinction in a common law court between the traditional roles of jury and judge. The court - traditionally the jury - finds the facts on the basis of evidence. The court - always the judge - ascertains the law with the benefit of argument. Ascertaining the law is a process of induction from one, or a combination, of two sources: the constitutional or statutory text and the previously decided cases. That distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law, together with that description of the process of ascertaining the law, works well enough for most purposes in most cases. * Solicitor-General of Australia. This paper was presented as the Sir N inian Stephen Lecture at the University of Newcastle on 14 August 2009. The Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture was established to mark the arrival of the first group of Bachelor of Laws students at the University of Newcastle in 1993. It is an annual event that is delivered by an eminent lawyer every academic year. 1 STEPHEN GAGELER (2008-9) But it can become blurred where the law to be ascertained is not clear or is not immutable. The principles of interpretation or precedent that govern the process of induction may in some courts and in some cases leave room for choice as to the meaning to be inferred from the constitutional or statutory text or as to the rule to be drawn from the previously decided cases. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

High Court of Australia

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2000-01 High Court of Australia Canberra ACT 7 December 2001 Dear Attorney, In accordance with Section 47 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979, I submit on behalf of the Court and with its approval a report relating to the administration of the affairs of the High Court of Australia under Section 17 of the Act for the year ended 30 June 2001, together with financial statements in respect of the year in the form approved by the Minister for Finance. Sub-section 47(3) of the Act requires you to cause a copy of this report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after its receipt by you. Yours sincerely, (C.M. DOOGAN) Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia The Honourable D. Williams, AM, QC, MP Attorney-General Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 CONTENTS Page PART I - PREAMBLE Aids to Access 4 PART II - INTRODUCTION Chief Justice Gleeson 5 Justice Gaudron 5 Justice McHugh 6 Justice Gummow 6 Justice Kirby 6 Justice Hayne 7 Justice Callinan 7 PART III - THE YEAR IN REVIEW Changes in Proceedings 8 Self Represented Litigants 8 The Court and the Public 8 Developments in Information Technology 8 Links and Visits 8 PART IV - BACKGROUND INFORMATION Establishment 9 Functions and Powers 9 Sittings of the Court 9 Seat of the Court 11 Appointment of Justices of the High Court 12 Composition of the Court 12 Former Chief Justices and Justices of the Court 13 PART V - ADMINISTRATION General 14 External Scrutiny 14 Ecologically Sustainable Development -

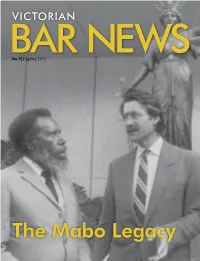

The Mabo Legacy the START of a REWARDING JOURNEY for VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS

No.152 Spring 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN The Mabo Legacy THE START OF A REWARDING JOURNEY FOR VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS. Behind the wheel of a BMW or MINI, what was once a typical commute can be transformed into a satisfying, rewarding journey. With renowned dynamic handling and refined luxurious interiors, it’s little wonder that both BMW and MINI epitomise the ultimate in driving pleasure. The BMW and MINI Corporate Programmes are not simply about making it easier to own some of the world’s safest, most advanced driving machines; they are about enhancing the entire experience of ownership. With a range of special member benefits, they’re our way of ensuring that our corporate customers are given the best BMW and MINI experience possible. BMW Melbourne, in conjunction with BMW Group Australia, is pleased to offer the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme to all members of The Victorian Bar, when you purchase a new BMW or MINI. Benefits include: BMW CORPORATE PROGRAMME. MINI CORPORATE PROGRAMME. Complimentary scheduled servicing for Complimentary scheduled servicing for 4 years / 60,000km 4 years / 60,000km Reduced dealer delivery charges Reduced dealer delivery charges Complimentary use of a BMW during scheduled Complimentary valet service servicing* Corporate finance rates to approved customers Door-to-door pick-up during scheduled servicing A dedicated Corporate Sales Manager at your Reduced rate on a BMW Driver Training course local MINI Garage Your spouse is also entitled to enjoy all the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme when they purchase a new BMW or MINI. -

“Women's Voices in Ancient and Modern Times”

“Women’s Voices in Ancient and Modern Times” Speech delivered at the ANU Law Students’ Society Women in Law Breakfast 22 March 2021 I acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land and pay my respects to their elders— past, present, and emerging. I acknowledge that sovereignty over this land was never ceded. I extend my respects to all First Nations people who may be present today. I acknowledge that, in Australia over the last 30 years, at least 442 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have died in custody. It is a pleasure to be speaking to a room of young women who will be part of the next generation of Australian and international lawyers. I hope that we will also see you in politics. In my youth, a very long time ago, the aspirational statement was “a woman’s place is in the House—and in the Senate”. As recent events show, that sentiment remains aspirational today. Women’s voices are still being devalued. Today, I will speak about the voices of women in ancient and modern democracies. Women in Ancient Greece Since ancient times, women’s voices have been silenced. While we could all name outstanding male Ancient Greek philosophers, poets, politicians, and physicians, how many of us know of eminent women from that time? The few women’s voices of which we do know are those of mythical figures. In Ancient Greece, the gods and goddesses walked among the populace, and people were ever mindful of their presence. They exerted a powerful influence. Who were the goddesses? Athena was a warrior, a judge, and a giver of wisdom, but she was born full-grown from her father (she had no mother) and she remained virginal. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

The Devil's Triangle

THE DEVIL’S TRIANGLE Civil liberties and the relationship between the law, the media and the parliament Bob Debus Attorney General of New South Wales 2000-2007 Sir Frank Kitto Lecture, University of New England, November 23rd 2012. This Lecture commemorates the great figure in Australian legal history Justice Sir Frank Kitto, who served on The High Court of Australia from 1950 to 1970 and was thereupon elected Chancellor of this University. As long ago as 1998 Justice Michael Kirby used this lecture to describe not only Sir Frank’s contribution to the law but his high integrity, demonstrated for instance, in the unequivocal judgment in which he joined the majority in Communist the seminal decision to strike down the Menzies Government’s Party Dissolution Act 1950. It was the beginning of the Cold War but Kitto was immune to the politics of the situation: “…it may have been thought (although never said in those more graceful days) that Justice Kitto was a ‘capital C conservative’. His skills were in the black letter law… He had just succeeded in a substantial brief for the banks in striking down the nationalisation scheme of the former Labor Government. Yet in less than a year, he performed his function as a judge of our highest court, in accordance with his understanding of the law and the Constitution precisely and only as his learning and 1 conscience dictated.” In the period 1976 to 1982 he was inaugural Chairman of The Australian Press Council. I venture to believe that he may have grudgingly approved the national defamation law finally achieved by the Commonwealth and State Attorneys General in 2005 after years of difficult negotiation. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

![Livingston V Commissioner of Stamp Duties (Qld) [1960] HCA 94; (1960) 107 CLR 411 (16 December 1960) HIGH COURT of AUSTRALIA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3501/livingston-v-commissioner-of-stamp-duties-qld-1960-hca-94-1960-107-clr-411-16-december-1960-high-court-of-australia-853501.webp)

Livingston V Commissioner of Stamp Duties (Qld) [1960] HCA 94; (1960) 107 CLR 411 (16 December 1960) HIGH COURT of AUSTRALIA

Livingston v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (Qld) [1960] HCA 94; (1960) 107 CLR 411 (16 December 1960) HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA LIVINGSTON v. COMMISSIONER OF STAMP DUTIES (Q.) [1960] HCA 94 ; (1960) 107 CLR 411 Private International Law High Court of Australia Dixon C.J.(1), Fullagar(2), Kitto(3), Menzies(4) and Windeyer(5) JJ. CATCHWORDS Private International Law - Succession Duty - Probate and Administration Duty - Death intestate of wife entitled to share in residue under her husband's will - Assessment of wife's estate for succession and administration duties on this share - Husband's estate not fully administered - Assets in New South Wales and Queensland - Husband, wife and executors of husband's will resident and domiciled in New South Wales - Place of administration of husband's estate New South Wales - Administrator of wife's estate denied liability of estate to duties - Appeals by petition to Supreme Court - Right of appeal - "Accountable party" - Nature of interest in estate not fully administered - Whether situated in Queensland - The Succession and Probate Duties Acts 1892 to 1952 (Q.), ss. 3, 4, 12, 43, 46, 47, 47A, 48, 50, 55. HEARING Brisbane, 1960, June 14, 15; Sydney, 1960, December 16. 16:12:1960 APPEAL and application for special leave to appeal from the Supreme Court of Queensland. DECISION December 16. The following written judgments were delivered:- DIXON C.J. By s. 48 of The Succession and Probate Duties Acts 1892 to 1952 chargeable with duty on being required by the Commissioner to deliver an account makes default in doing so the Commissioner may, by summons before a judge of the Supreme Court in chambers call upon such person to show cause why he should not deliver the account and pay the duty and costs, and thereupon such order shall be made as the judge thinks just. -

Admission of Lawyers∗

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES BANCO COURT ADMISSION OF LAWYERS∗ 1. Now that the formal part of the proceedings has ended, I would like to warmly welcome you to the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Present with me on the Bench today are two other Justices of the Supreme Court. Together, we constitute the Court that has, in exercise of its jurisdiction, admitted you to practice. 2. As we gather here today, I would like to begin by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation, and pay my respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging. We recognise the longstanding and enduring customs and traditions of Australia’s First Nations, and acknowledge with deep regret the role our legal system has had in perpetrating many injustices against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. 3. To all the new lawyers here today, welcome to the legal profession. Today is a day for celebration. You have all worked extremely hard to get here, through caffeine-fuelled nights and obscure problem questions, reading countless wafer-thin pages of textbook and more cases than you can hope to remember. You have entered the world of eggshell skulls, encountered the mysterious “reasonable person” and have understood that the Constitution consists of so much more than “the vibe of the thing”. 4. In becoming a lawyer, you have today joined a centuries-old profession with ancient origins.1 The custom of advocates swearing an admissions oath ∗ I express my thanks to my Research Director, Ms Rosie Davidson, for her assistance in the preparation of this address.